Abstract

Adenomyosis is identified by the enlargement of the uterus secondary to such areas of the endometrium as the endometrial glands and stroma located deep in the myometrium, which causes its hyperplasia and hypertrophy. The most common signs of the development of adenomyosis in a patient are copious menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea. However, it should be borne in mind that in some patients, the disease may be asymptomatic. Despite the wide abundance of imaging and other diagnostic methods for diagnosing adenomyosis, there are currently no standard verified diagnostic criteria for pathologists. In addition, women with adenomyosis often have other concomitant gynaecological diseases, such as endometriosis or leiomyomas, which makes it difficult to diagnose and choose the optimal treatment for patients. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to highlight up-to-date and relevant information for the practitioner about the epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostics and treatment options for adenomyosis. Sources from four databases (PubMed, Web of Science, Elsevier and Google Scholar) were used to search for data. As a result of a literature review, it was established that the “gold” standard for the diagnostics of adenomyosis is histological research methods, in particular, biopsy performed during hysteroscopy or laparoscopy, whereas imaging methods (transvaginal sonography, magnetic resonance imaging) are more often used for differential diagnostics of adenomyosis with other diseases. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging allows for a better differential diagnostics between adenomyosis and myomatosis and helps to recognise the disease at an early stage. Regarding treatment, there is currently no particular therapy and algorithms for the treatment of adenomyosis, which is primarily due to the lack of precise criteria for the diagnostics of the disease. However, the most effective therapeutic methods at the present stage are the use of aromatase inhibitors and gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists, whilst minimally invasive techniques, in particular, endometrial ablation and uterine artery embolisation, are becoming increasingly popular amongst surgical techniques.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

It was established that adenomyosis can be diagnosed not only in the traditional way, that is, histologically after hysterectomy, but also with the help of a biopsy obtained during hysteroscopy and laparoscopy. It is determined that there is no universal and effective method of treating adenomyosis, because clear criteria for diagnosing the disease have not yet been established, medical or surgical treatment is established according to the specifics of the course of the disease. |

Introduction

Adenomyosis is a heterogeneous gynaecological disease characterised by polymorphism of clinical manifestations [1]. The exact aetiology of adenomyosis remains unclear. However, some theories suggest invagination of the endometrium into the myometrium, whilst others suggest the metaplasia of stem cells [2]. New theories of the pathophysiology of endometriosis may also change the understanding of adenomyosis. For example, P. Vigano et al. [3] established that as a result of genetic–epigenetic changes, intracellular aromatase activity and oestrogen production are disrupted, which leads to the formation of inflammatory fibrous endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus. Thus, it can be assumed that such changes can also affect the implantation of the endometrium into the myometrium, causing a typical clinic of adenomyosis, including menorrhagia, chronic pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea and infertility [4]. Adenomyosis is most often classified according to the form (diffuse, nodular, diffuse–nodular, cystic) and the degree of the disease. According to M. Levgur et al. [5], there are four degrees of adenomyosis:

-

Grade I: pathological foci are localised in the area of the submucosal layer of the uterus and affect less than 40% of the thickness of the myometrium;

-

Grade II: foci grow deeper, occupying 40–80% of the myometrial wall;

-

Grade III: the disease captures > 80% of the thickness of the myometrium;

-

Grade IV: pathological foci grow through the entire area of the myometrium, the serous lining of the uterus with possible damage to the peritoneum and pelvic organs.

The true frequency of detection of adenomyosis is unknown. The average frequency of adenomyosis during hysterectomy is 20–30% [6]. Cystic adenomyosis can be present in 24% of samples after hysterectomy and is usually found in multipara patients and those over the age of 30 years [7]. However, it is also worth considering the development of a rare form of cystic adenomyosis—juvenile cystic adenomyosis, which occurs in young girls under 30 years old [8]. Sometimes this form can be misdiagnosed as an unreported rudimentary horn, which negatively affects the diagnostics of adenomyosis and may result in irreversible consequences in the future [9]. Moreover, the recognition of the disease is also complicated by the frequent presence of concomitant pathologies, regardless of the form of adenomyosis, which also affects the complexity and effectiveness of treatment of such patients [6]. Historically, the diagnosis of this disease was made after hysterectomy in women at later reproductive age. However, with the development and widespread use of noninvasive imaging methods (ultrasound, computed tomography—CT, magnetic resonance imaging—MRI), it was found that adenomyosis can also occur in women under 30 years of age and even in adolescents [10]. Some researchers argue that such a large age range in the diagnostics of adenomyosis may be due to the lack of unified standard diagnostic criteria for both imaging methods and the results of pathological studies [11]. There may also be differences in the literature due to factors such as the potential bias of the pathologist in making the diagnosis due to knowledge of the patient’s anamnesis or differences in the number of tissue samples examined [12].

Moreover, due to the poorly studied pathophysiology and nature of this disease, treatment is not standardised and currently there are no guidelines that give preference to one treatment method over another [13]. For many years, adenomyosis has been treated both medically and surgically, sometimes sacrificing the fertility of the patient [14]. Until recently, hysterectomy was the only radical method of treating patients with adenomyosis who completed childbirth. More recently, other treatment options have been evaluated. For example, adenomyosis, like endometriosis, is an oestrogen-sensitive condition, which served as the basis for drug treatment aimed at the regression of adenomyotic lesions by controlling the hormonal environment [15]. On the other hand, surgical approaches that preserve fertility in young women are becoming increasingly popular in practice. However, currently, there are no agreed recommendations that doctors could operate on and follow when developing a therapeutic strategy for each patient, which as a result may contribute to the development of irreversible consequences [13]. Thus, the large polymorphism of clinical variants of adenomyosis and the severity of the consequences as a result of its manifestation in the absence of clear algorithms for the diagnostics and therapy of this pathology make it urgent to create criteria for its detection and subsequent early effective treatment.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to search and evaluate the currently existing options for the diagnostics and treatment of adenomyosis and compare their effectiveness in the fight against this disease.

Materials and methods

A preliminary review of the literature was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of PRISMA using an interactive group approach with regular team meetings to discuss progress and reach consensus on the subsequent writing of the paper [16]. The literature search was conducted in the databases Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed and Elsevier in the period from January 1, 2000 to March 12, 2022. The purpose was to effectively identify databases that are most likely to include relevant papers. The research was limited, as the search was conducted in English and Russian. In the future, according to the selection criteria, the studies included in the review were selected. The selection criteria for inclusion were deliberately broad. Publications of the last 5–10 years were proposed for consideration, in which the features of the diagnostics and treatment of adenomyosis were considered. Preference was given to original clinical studies and meta-analyses, which examined the effectiveness of using a particular method of diagnostics or treatment of the disease. Publications with poorly designed research or works where the attention was paid to advertising methods of diagnostics or treatment were excluded from the systematic review.

In this systematic review, the main initial terms for the search for scientific publications were “adenomyosis”, “diagnostics of adenomyosis” and “treatment of adenomyosis” to identify different methods of diagnostics and treatment of the disease. The subsequent search for each of the methods of treatment and diagnostics of adenomyosis was carried out using the terms “3D-transvaginal sonography”, “2D-transvaginal sonography”, “magnetic resonance imaging” (MRI), “hysterectomy”, “biopsy”, “drug treatment”, “surgical treatment”, “non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs” (NSAID), “oral contraceptives”, “gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist”, “Danazol”, “aromatase inhibitors” (AI), “antiplatelet therapy”, “dopamine agonists”, “oxytocin antagonists”, “uterine resection”, “preservation of the uterus”, “uterine artery embolization” and “radiofrequency ablation of uterine arteries”. The main types of studies that were subject to subsequent review were the following:

-

Randomised controlled trials with a minimum number of patients amongst ten patients;

-

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses;

-

Studies of diagnostic methods in which particular symptoms are given that allow diagnosing adenomyosis;

-

Scientific publications of treatment methods, in which a statistical analysis of changes in the clinical status of a patient due to the use of a particular method of treatment of adenomyosis is discussed and carried out.

Pre-clinical in vitro studies, case series, and clinical cases were also not included in the review. In addition, the studies based on the use of questionnaires and surveys without subsequent statistical processing of data and all works that did not meet the inclusion criteria were subject to exclusion. As a result of the literature search in the specified databases for keywords and inclusion and exclusion criteria, the initialised study investigated a total of 137 papers. After that, the two authors, independently of each other, additionally analysed the selected publications for the element of their quality and expediency of use. Any questions and disagreements that arose during the analysis process were resolved collectively at regular meetings of the team of authors. As a result, a total of 69 publications evaluating different methods of diagnostics and treatment of adenomyosis were included in this review.

Results and discussion

Histological examination methods are the basic diagnostic procedures for confirming adenomyosis in a patient. Historically, the pathology was diagnosed based on histological data after hysterectomy, in which the uterus is globally enlarged, the surface is smooth, when cut in half, the incision surface often looks spongy with areas of focal haemorrhages. Microscopically, adenomyosis is diagnosed when endometrial tissue is found inside the myometrium. The minimum distance required for diagnostics ranges from half to two fields of vision at low magnification from the junction of the endomyometrium or the minimum depth of invasion from 1 to 4 mm [17]. At the present stage of medical development, the diagnostics of adenomyosis is also carried out mainly using histological research methods, for example, hysteroscopic and laparoscopic biopsy [18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In 1992, A.M. McCausland [18] concluded that a hysteroscopic biopsy of the myometrium could diagnose adenomyosis. Earlier it was reported that adenomyosis has no pathognomonic signs during hysteroscopy. However, A. Di Spiezio Sard et al. [19] in 2017 have established that hysteroscopy is a useful tool in examining patients since it allows visualising the uterine cavity, assessing other potential anomalies, and obtaining a biopsy of the endometrium or myometrium under direct imaging control. Scientists have also found that an irregular endometrium with endometrial defects, cystic haemorrhagic lesions and altered vascularisation may be associated with the presence of adenomyosis in a woman, which can be considered criteria for diagnostics. Therewith, A. Graziano et al. [20] have reported surface openings in the endometrial cavity, hypervascularisation, and cystic haemorrhagic lesions as possible signs of adenomyosis.

Thus, a minimally invasive, tissue-sparing biopsy can be obtained as evidence of the disease. In a cross-sectional study involving 292 patients with clinical signs of adenomyosis, D. Dakhly, et al. [21] examined the accuracy of endomyometrial biopsy obtained by hysteroscopy for histopathological confirmation of adenomyosis, which increased the specificity of adenomyosis diagnostics from 60 to 89%. Earlier it was reported that this method carries a low diagnostic value. For example, J.J. Brosens and F.G. Barker [22] performed 8 needle biopsies on 27 hysterectomy samples with adenomyosis and established that the estimated sensitivity of 2 random biopsies ranged from 2.3 to 56%, whilst the sensitivity increased with the number of biopsies and the depth of adenomyosis. Given the invasiveness of the method and possible side effects, this type of biopsy was not very popular. However, J. Cherng-Jye et al. [23] recently discovered that the sensitivity of laparoscopic biopsy ranges from 62 to 98%. They performed 100 needle biopsies and found that a needle biopsy of the myometrium has a much higher sensitivity, which may be associated with pre-diagnosed myometrial lesions and requires subsequent studies.

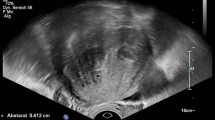

It was established that laparoscopic biopsy during surgical interventions in women with suspected adenomyosis can considerably improve the chance of confirming the diagnosis. Therewith, the characteristic signs for the disease will be enlargement of the uterus, pulvinate resistance of the uterine wall, cystic subserous haemorrhagic lesions and a “blue sign” when conducting a test with a blue dye. Therewith, guided biopsies without previously diagnosed suspicious lesions are useless due to unsatisfactory sensitivity and specificity for histological confirmation of adenomyosis [24]. Usually, a histological examination is sufficient to diagnose adenomyosis but the use of images can help in the differential diagnostics. The two most common methods are magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and transvaginal sonography. However, there are currently no standard criteria for diagnostic imaging of adenomyosis using these methods. In recent years, transvaginal sonography has been increasingly used in general medical practice as a fast and relatively inexpensive method of diagnosing adenomyosis with a sensitivity of 65–81% and a specificity of 65–100%, depending on the study [25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

N. Di Donato et al. [25] described the following nine main signs of adenomyosis in 2D transvaginal sonography: heterogeneous myometrium, hyperechoic or hypoechoic linear striation in the myometrium, anechoic lacunae or cysts of the myometrium, subendometrial microcysts, asymmetric thickening of the myometrium of the uterine wall, global enlargement of the uterus, the so-called question mark, thickening of the transition zone and hyperechoic areas of the myometrium. A. Graziano et al. [20] also established the same signs of adenomyosis in their work, adding that this method with the above criteria makes it much easier for every doctor to diagnose adenomyosis. Therewith, in their systematic review, M. Habiba and G. Benagiano [26] concluded that the presence of myometrial cysts, linear striation of the myometrium and heterogeneous myometrium increases the likelihood of adenomyosis, and D. Decter et al. [27] reported that the highest accuracy in the sonographic diagnostics of adenomyosis is played by the subendometrial linear striation of the myometrium.

The efficiency of using 2D-transvaginal sonography varies with different studies. For example, N. Di Donato et al. [25] in their study found that amongst 50 patients, the sensitivity of the technique is 92%, and the specificity is 88%. 92% sensitivity and 88% specificity of 2D-transvaginal sonography were reported in a group of 50 patients who were prescribed hysterectomy due to symptoms of endometriosis or adenomyosis. Therewith, D. Dakhly et al. [21] established that the accuracy of the diagnostics can considerably increase with a combination of transvaginal sonography and biopsy, which gives rise to their mutual use. In the diagnostics of adenomyosis using 2D-transvaginal sonography, the sensitivity of the method was 83.95% and the specificity was 60%, whereas, in combination with biopsy, the latter increased to 89%. Recent studies show that 3D-transvaginal sonography has a greater diagnostic value than 2D-transvaginal sonography due to a better assessment of the connective zone altered by adenomyosis, which allows diagnosing the disease at its early stages [11]. For example, C.K. Rasmussen et al. [28] have shown good accuracy in adenomyosis diagnostics using 3D-transvaginal sonography of the coronary section of the uterus with assessment and measurement of the transition zone. L. Vandermeulen et al. [29] also demonstrated the high diagnostic value of 3D-transvaginal sonography in their study due to the combination of targeted biopsy and ultrasound. The most characteristic parameters of 3D-transvaginal sonography were the following: connective zone thickness > 12 mm, myometrial asymmetry and hypoechoic striation, considering which the diagnostic accuracy reached 90%.

Moreover, recent studies report that due to the specific features of myometrial vascularisation in adenomyosis, exceptional diagnostic accuracy can be achieved with the additional use of Dopplerography after transvaginal sonography. For example, K. Sharma et al. [30] established that in 93% of cases of adenomyosis, pathological foci had central vascularisation, whereas with leiomyoma, peripheral vascularisation was more often visualised (in 89% of cases), which greatly simplified the differential diagnostics of adenomyosis and uterine fibroids. An additional sonographic method for diagnosing uterine tumours is sonoelastography, which measures the stretching and stiffness of tissues. In their study, V. Săsăran et al. [31] have shown that myometrium, fibroids and adenomyosis have different elastographic characteristics and colour patterns, which simplified the diagnostics of each of these diseases. MRI is another method of diagnosing adenomyosis. However, due to the high cost, it is more often used in complex clinical cases, when other methods listed above do not allow confidently diagnosing adenomyosis. According to C.P. Stamatopoulos et al. [32], the sensitivity of MRI in adenomyosis is 46.1%, the specificity is 99.2% and the prognostic value is 92.3%, which allows diagnosing adenomyosis at the early stages. Scientists have found that the most frequent MRI criteria for adenomyosis were focal or diffuse thickening of the myometrial transition zone, as well as zones (spots) of low and high signal intensity in the T2 mode. M. Bazot et al. [33] reported a sensitivity of 77.5%, specificity of 92.5% and prognostic value 83 of 8% in a prospective study involving 120 patients. As a result of the study, the following MRI criteria for adenomyosis were established: the thickness of the connective zone > 12 mm and its ratio to the thickness of the myometrium > 40% and the presence of a myometrial spot with a high signal intensity.

Notably, in everyday practice, the diagnostic tool of transvaginal sonography is more accessible and economical than MRI, and in many cases, the accuracy of transvaginal sonography is similar or even higher than in MRI, especially in combination with 3D and Doppler. However, in cases of adenomyosis in the form of a limited adenomyoma or adenomyotic cystic area or polyp, MRI allows describing in more detail the localisation, the size of the formation and making a differential diagnosis, especially in the preoperative planning of surgical resection of focal or diffuse adenomyosis in the treatment of infertility [34, 35]. Treatment options for adenomyosis include both medical and surgical interventions. However, determining the optimal treatment for patients can be difficult, which is primarily due to the lack of agreed criteria for adenomyosis diagnostics, which affects the creation of criteria for the effectiveness of treatment. Moreover, the symptoms in patients may be heterogeneous and adenomyosis may be associated with other gynaecological conditions, which, combined with an insufficient number of randomised controlled trials of high quality, complicates the construction of accurate algorithms for the treatment of this pathology [36]. However, today there are numerous therapeutic and surgical methods of treating adenomyosis that have sufficient effectiveness for their use by a practising physician.

Women with dysmenorrhea, which often occurs with adenomyosis, have elevated prostaglandin levels, which can lead to painful seizures. Thus, by inhibiting cyclooxygenase, an enzyme that is involved in the production of prostaglandins, women may experience an improvement in symptoms when taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [37]. For example, J. Marjoribanks et al. [38] compared all non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with placebo in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea and concluded that NSAIDs are considerably more effective for pain relief than placebo in women with dysmenorrhea; however, the overall side effect also increased. Notably, these drugs provide only symptomatic treatment and have no effect on the very process of development and progression of adenomyosis. Oral contraceptives and progestins have also been approved as a symptomatic treatment for dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding. It has been established that these drugs help to neutralise symptoms, causing amenorrhea, and for a short period can also cause regression of adenomyosis. However, due to the lack of randomised controlled trials with a wide sample, some experts believe that these treatments are ineffective in the treatment of adenomyosis, which requires further research [37].

The intrauterine device with levonorgestrel (Mirena) acts by releasing 20 mcg of levonorgestrel per day for up to 5 years. It is believed that symptomatic improvement occurs secondarily due to two mechanisms. First, levonorgestrel causes decidualisation of the endometrium, which leads to a decrease in menstrual discharge. Second, it acts on the foci of adenomyosis, causing the downregulation of oestrogen receptors. This leads to a decrease in the size of ectopic foci of the endometrium, allowing the uterus to contract more efficiently, reducing menstrual blood loss and leading to a decrease in prostaglandin production, reducing dysmenorrhea. Bleeding and dysmenorrhea, as well as X-ray changes after the introduction of levonorgestrel-intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) [39]. In a study involving 95 women, H. Maia et al. [40] evaluated the effectiveness of an LNG-IUS with levonorgestrel after endometrial resection for the treatment of menorrhagia caused by adenomyosis. A considerably higher level of amenorrhea was found in the LNG-IUS group compared to the control group (100% vs. 9%, respectively). It has also been shown that the LNG-IUS can be used in the future as an alternative to hysterectomy due to the possibility of treating adenomyosis both through decidualisation and endometrial atrophy and through suppression of oestrogen receptors due to high progestin release. In confirmation of this, the study by O. Ozdegirmenci et al. [41], where the use of LNG-IUS was compared with hysterectomy for adenomyosis and haemoglobin levels measured after treatment with any of the methods 6 months and a year later were comparable in both groups.

J. Sheng et al. [42] examined the effectiveness of LNG-IUS in 94 women with moderate or severe dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis diagnosed with transvaginal sonography. They observed women for 3 years and found a considerable improvement in dysmenorrhea indicators: the average baseline score of 77.9 decreased to 11.8 36 months after installation (p < 0.001). They also found a decrease in uterine volume and serum CA-125 levels. The overall level of patient satisfaction was 72.5%. In a recent systematic review, Abbass et al. established that LNG-IUS can be used as a highly effective treatment option for adenomyosis. It was found that the use of LNG-IUS leads to a considerable reduction in pain from 3 months after the start of treatment. Similar results were demonstrated when assessing heavy menstrual bleeding and uterine volume after 6 and 36 months. It has also been shown that haemoglobin levels increase considerably after treatment with hormonal LNG-IUS after 6 months and last up to 12 months after administration. L. Zhang et al. [43] also investigated the long-term clinical effects of LNG-IUS in 47 women diagnosed with adenomyosis. They found that during its use, the indicators of the graphical blood loss assessment table considerably decreased after the installation of Mirena both in patients with menorrhagia (118 ± 13 compared to 29 ± 33, p < 0.01) and in patients with normal menstruation (82 ± 15 compared to 14 ± 13, p < 0.01). Therewith, in patients with menorrhagia, a more considerable decrease in the pictorial blood loss assessment chart index (PBAC) was observed than in patients with normal menstruation (90 ± 35 vs. 69 ± 19, p < 0.01), and the visual analogue scale index (VAS) considerably decreased after the Mirena installation compared to the condition before treatment. Thus, scientists have proved that Mirena is effective and safe for the long-term treatment of adenomyosis.

Danazol is an androgenic hormone used in the treatment of endometriosis to reduce ectopic endometrial tissue. The drug acts by suppressing the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) by the pituitary gland and, consequently, causes atrophy of both normal and ectopic endometrial tissue [41]. Systemic treatment with Danazol has been shown to reduce the expression of cytochrome P-450 aromatase in the affected ectopic endometrium; this may contribute to improving symptoms and reducing the size of the uterus in patients treated with Danazol. However, many patients do not tolerate it well due to its side-effect profile, which may include acne, depression, deepening of the voice, hirsutism, flashes, decreased levels of high-density lipoproteins, increased concentrations of liver enzymes, oily skin, muscle spasms, breast size reduction and weight gain [37]. In vitro studies have shown that Danazol affects cell proliferation by inducing apoptosis and regulating deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis. S. Vannuccini et al. [44] established that stromal and glandular cells in pathological foci of adenomyosis are characterised by a decrease in the number of oestrogen receptors. Adenomyosis glands and stromal cells analysed after systemic treatment with Danazol show a decrease in the concentration of the oestrogen receptor and bcl-2 protein, one of the main markers of apoptosis, whilst increasing apoptotic cell necrosis. Danazol also regulates the proliferation of immunocompetent cells, thereby directly affecting inflammatory reactions in the uterus.

In the study by H. Ota et al. [45] (the only randomised controlled trial of Danazol), hysterectomy was compared with a 4-month treatment with Danazol at a dose of 400 mg daily. As a result, it was found that autoantibody levels after treatment and antiphospholipid levels were reduced due to the inhibitory effect of Danazol on lymphocyte proliferation and their function. M. Igarashi [46] used an intrauterine device containing 175 mg of Danazol in their study. The treatment led to an effective reduction in the size of the uterus, which allowed 66.6% of patients to become pregnant. In addition, when increasing the dose of Danazol to 300–400 mg, scientists observed a considerable decrease in pain syndrome in women, which, against the background of good tolerability of the drug, indicated its good efficacy and safety of use [47]. S. Luisi et al. [48] established that oral administration of 200 mg of Danazol effectively reduces copious menstrual bleeding and pain in women with adenomyosis. In turn, C. Tosti et al. [49] demonstrated an improvement in pain symptoms and a decrease in blood loss in uterine bleeding after 6 months of treatment for adenomyosis. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists are peptide compounds with a structure similar to natural GnRH, which inhibit the reproductive system due to direct antagonistic action on GnRH receptors in the pituitary gland, blocking the secretion of gonadotropins [50]. The first report on the use of GnRH antagonists for the treatment of adenomyosis was published by D. Grow and R.B. Filer [51] in 1991. They reported a 65% decrease in uterine volume after 4 months of treatment, as well as amenorrhea and improvement in severe dysmenorrhea.

Two double blind randomised trials of phase 3 involving women with endometriosis who received different doses of Elagolix, an oral non-peptide GnRH antibody, have recently been published. Both Elagolix regimens were effective in reducing dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain over 6 months in women with moderate to severe endometriosis-related pain. The mechanism of action of GnRH antibodies differs from the mechanism of action of GnRH analogues, which, after the initial phase of stimulation, reduces the sensitivity of GnRH receptors in the pituitary gland and subsequently causes depletion of pituitary gonadotropins and complete suppression of estradiol. GnRH antibodies do not cause either suppression or desensitisation of receptors since they act competitively, preventing the binding of endogenous GnRH and activation of its pituitary receptor. Thus, depending on the dose of the administered antagonist, the suppression of estradiol can be modulated [52, 53]. Cytochrome P-450 aromatase takes part in the conversion of androstenedione and testosterone into estrone and estradiol, respectively. Its expression is observed both in the eutopic and ectopic endometrium in patients with endometriosis [44].

The first documented use of aromatase inhibitors in adenomyosis was reported in a woman with severe adenomyosis refractory to GnRH analogues and Danazol, who wanted to preserve her fertility. Anastrozole was administered orally for 16 weeks in combination with GnRH analogues to suppress the production of oestrogen by the ovaries. The decrease in uterine volume was 60% after 8 weeks of treatment and the patient did not have AMB for 6 months after stopping the administration of AI. The results of a randomised controlled trial comparing treatment for 3 months with an aromatase inhibitor (letrozole 2.5 mg/day) and goserelin 3.6 mg monthly showed that AI have the same effectiveness as GnRH analogues in reducing the volume of adenomyoma and improving symptoms. In fact, with both treatment options, there was a considerable difference in the volume of the uterus after 3 months without a corresponding change in the area of adenomyosis (41% vs. 49%) at the end of the study [54]. IA seems to have a promising future for the treatment of adenomyosis in cases of resistance to other treatments, even though more research is needed.

The hysterectomy method provides the definitive treatment for patients with adenomyosis and has historically been the primary diagnostic and therapeutic option for patients. This is usually the treatment of choice for patients with significant symptoms who have completed childbirth. This procedure can be completed by laparoscopy, vaginally or abdominally. Amongst these options, vaginal hysterectomy is preferable to abdominal hysterectomy due to faster recovery and lower morbidity. However, it should be noted that there is a possibility that patients may still experience pelvic pain after hysterectomy [55]. In a study conducted by T. Stovall and R.L. Summitt [56], scientists reviewed the long-term results of 99 women who underwent hysterectomy (vaginal or abdominal) for pelvic pain lasting at least 6 months. Patients were excluded from the study if they had symptoms, signs, previously documented data or results of ectopic disease during surgery. Histopathological studies helped to identify adenomyosis in 20.2%, leiomyoma in 12.1% and both leiomyoma and adenomyosis in 2.02%. Patients were observed for an average of 21.6 months after surgery and 77.8% have shown considerable improvement. However, 22.2% had persistent pelvic pain. Of these patients with adenomyosis, 22.2% retained pelvic pain after hysterectomy.

Endometrial ablation and hysteroscopic resection can be used as a treatment option in patients who have completed childbirth. Usually, ablation procedures are classified as non-resectoscopic, such as bipolar radio frequency, cryotherapy, hot water circulation, microwave and heat balloon, or as resectoscopic, including wire loop resection, laser or roller ablation. A common problem with ablation and resection procedures is that the depth of adenomyotic lesions limits the success of treatment. The deep ectopic endometrium can get stuck behind the ablated edge, causing pain and bleeding. Resection is often limited to superficial lesions, as there is a risk of causing considerable bleeding from arteries located about 5 mm below the surface of the myometrium [57] V. McCausland and A. McCausland [58] examined 50 patients diagnosed with adenomyosis 3.5 years after endometrial ablation and found that patients with superficial adenomyosis (< 2 mm) had good results, whereas patients with deep adenomyosis (> 2 mm) had poor results after ablation. They reported that the electrode roller has a coagulation effect of about 2–3 mm into the myometrium and, therefore, can destroy the endometrium and the surrounding hypertrophied dysfunctional unstriated muscles. However, as the ectopic endometrium penetrates further into the myometrium, less destruction of the tissue occurs. They also found that patients with bleeding after ablation responded well to progesterone treatment if they had superficial adenomyosis but progesterone therapy was often ineffective in patients with deep adenomyosis.

Uterine artery embolisation is another method of treating symptoms secondary to dysmenorrhea. Patients report an improvement in symptoms after uterine artery embolisation with a considerable reduction in symptoms of heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea [44, 59, 60]. Earlier studies demonstrate the long-term improvement of patient symptoms (in more than 60% of patients) and short-term decrease in uterine volume (in more than 20% of patients), especially in vascular lesions [44]. Recent research, for example, the study of M. Dueholm [59], demonstrate up to 67% of long-term (40 months) treatment success and up to 72% of patient satisfaction, respectively. In turn, in a meta-analysis by A. de Bruijn et al. [60], scientists demonstrated that after embolisation, short-term improvement was achieved in 89.6% of patients, whilst long-term improvement was achieved in 74%, which indicates a high efficiency of the method. Excision of adenomyotic foci can be completed if the ectopic endometrium is well defined. However, lesions are often indistinctly defined and adenomyosis is present diffusely throughout the myometrium. Subsequently, the success rate after excision treatment is low and makes 50%.

P. Wang et al. [61] prospectively examined 165 women who underwent conservative adenomyomectomy and compared the outcomes of patients who underwent surgery alone compared with women who underwent surgery and then underwent postoperative treatment with GnRH agonists. After treatment, there was a considerable decrease in dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual bleeding in both treatment groups. Women with a higher probability of recurring symptoms after 2 years of follow-up were women with higher preoperative serum CA-125 levels, as well as with higher initial copious menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea compared to women who did not have recurring symptoms. In addition, this study has shown promising reproductive opportunities and outcomes after treatment; 71 women were sexually active and did not use contraceptives, 55 of them became pregnant. The frequency of clinical pregnancy was 77.5%, 49 women (69.0%) gave birth successfully. Electrocoagulation of the myometrium by laparoscopy or hysteroscopy can cause a decrease in adenomyosis secondary to necrosis. This method is used for both diffuse and localised disease and may be an option for symptomatic patients with advanced adenomyosis, in whom drug therapy has proved ineffective when excision is impossible and they want to preserve the uterus but do not want to get pregnant [62].

Published reports on electrocoagulation of the myometrium are limited and the success rate of treatment ranges from 55 to 70%. For example, C. Wood et al. [63] reported that seven patients received electrocoagulation of myometrium. Four (57.1%) of these patients were found cured, which means that they had decreased copious menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea that did not require further treatment. Thus, electrocoagulation of the myometrium can be used for the surgical treatment of adenomyosis; however, the absence of large randomised studies of the effectiveness of this method does not allow it to be confidently recommended for widespread use. Myometrial reduction is an approach to the treatment of patients with diffuse adenomyosis by removing abnormal tissue and then performing metroplasty during laparoscopy or laparotomy. Three main approaches were described. The classical method of repositioning, in which the uterus is dissected longitudinally along the midline and resection of the anterior and posterior parts of the myometrium is performed was demonstrated by M. Nishida et al. [64]. They found that this method was not very successful because the women developed adenomyosis and required a hysterectomy within a year. Y. Gao et al. [65] described the second method; in their modified method, a transverse H-section is performed. They compared the 2 methods in 57 women and as a result found that despite the absence of differences in the time of surgery, blood loss and volume of the removed sample, in the modified group, there was a greater reduction in pain and a better course of the postoperative period.

In 2014, M. Nishida et al. [66] described a new method of surgical treatment of diffuse uterine adenomyosis. They conducted it on 44 patients with diffuse adenomyosis. After the operation, menstruation resumed in all women for 3 months, dysmenorrhea, menstrual blood loss, and anaemia decreased. In addition, two women became pregnant after surgery. Removal of diffuse adenomyosis is problematic in patients who want to get pregnant since excision of the disease leads to a decrease in the volume of the uterus. This causes concern in future pregnancies since a decrease in the myometrium may predispose to miscarriage or premature birth. In addition, this method causes scarring of the uterus, which may contain small areas of adenomyosis. This leads to a decrease in the strength of the uterine wall and an increase in the risk of uterine rupture. Although the incidence of pregnancy after these procedures was low, these small studies showed an improvement in dysmenorrhea and copious menstrual bleeding, and therefore these conservative operations may be an option for patients with symptomatic diffuse adenomyosis who want to preserve their uterus.

Removing areas of adenomyosis in patients who want to preserve their fertility is a difficult task. As described earlier, conservative surgery can lead to scarring and negatively affect fertility. Thus, focussed ultrasound surgery under the control of magnetic resonance can provide an alternative treatment for patients with adenomyosis who want to preserve fertility. The treatment causes cell death and necrosis of the target adenomyotic tissue, preserving the surrounding myometrium and the uterine wall. Ultrasound beams focus on the target and cause thermal coagulation and subsequent necrosis. When using ultrasound surgery under the control of MRI, excellent anatomical resolution and high thermal imaging sensitivity are achieved, which allows achieving great results in the treatment of adenomyosis [67]. For example, H. Fukinishi et al., reviewed 20 cases of treatment using this method and found that after treatment, patients had considerably lower average uterine volume and lower scores associated with copious menstrual bleeding and volume for a period of 3 to 6 months after treatment [68]. The clinical effectiveness of the method is also confirmed by the study of L. Shui et al. [69], who found that as a result of treatment with high-intensity ultrasound, the symptoms of adenomyosis and the general condition of patients improved by 84.7, 84.7 and 82.3%, respectively, in 3 months, 1 year and 2 years after treatment. Thus, this method is an effective and safe method of treating symptomatic adenomyosis and can be considered an alternative method of preserving the uterus in women with this disease [70].

Conclusion

Adenomyosis is diagnosed when the endometrial tissue is abnormally located in the myometrium. The true frequency of this disease is unknown but advances in imaging allow detecting it more often in women. Risk factors for the disease include oestrogen exposure, parity and prior uterine surgery. Conventionally, the diagnosis was made only histologically after hysterectomy. However, studies have shown that a diagnosis can be made using a biopsy obtained during hysteroscopy and laparoscopy. Noninvasive imaging can also be used to aid in the differential diagnostics. The two most commonly studied imaging methods are transvaginal sonography and MRI. Many studies have shown that transvaginal sonography and MRI have decent sensitivity and specificity for adenomyosis. However, there are no general diagnostic criteria in the literature, which makes it difficult to effectively diagnose the disease.

The most frequently reported results of transvaginal sonography are heterogeneous myometrial echotexture, obscure foci of abnormal myometrial echotexture, myometrial cysts and spherical asymmetric uterus. Recent studies show that the use of 3D-transvaginal sonography is superior to 2D-transvaginal sonography for the diagnostics of adenomyosis and may allow the diagnostics of the disease at an early stage. The most frequent findings on MRI include a large, regular, asymmetric uterus without leiomyomas, abnormal myometrial signal intensity, thickening of the junction zone and high-intensity myometrial foci on T1-weighted images. Treatment of patients may include such medication as NSAIDs, oral contraceptives, progestins, LNG-IUS, Danazol, GnRH agonists and aromatase inhibitors, or such surgical options as ablation and resection of the endometrium, uterine artery embolisation, excision of the myometrium or adenomyoma, electrocoagulation of the myometrium, reduction of the myometrium, focussing under the control of MRI ultrasound surgery, and for final treatment—hysterectomy. The lack of properly randomised trials explains the lack of evidence in favour of a particular treatment method. Factors to consider when deciding on treatment include age, severity of symptoms, desire for future fertility and comorbidities such as endometriosis and fibroids.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Zhai J, Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, Giudice LC (2020) Adenomyosis: mechanisms and pathogenesis. Semin Reprod Med 38(2–03):129–143

García-Solares J, Donnez J, Donnez O, Dolmans M-M (2018) Pathogenesis of uterine adenomyosis: invagination or metaplasia? Fertil Steril 109:371–379

Vigano P, Candiani M, Monno A, Giacomini E, Vercellini P, Somigliana E (2018) Time to redefine endometriosis including its pro-fibrotic nature. Hum Reprod 33:347–352

Koninckx PR, Ussia A, Adamyan L, Tahlak M, Keckstein J, Wattiez A, Martin DC (2021) The epidemiology of endometriosis is poorly known as the pathophysiology and diagnosis are unclear. Best Practice Res Clin Obstetr Gynaecol 71:14–26

Levgur M, Abadi MA, Tucker A (2000) Adenomyosis: symptoms, histology, and pregnancy terminations. Obstet Gynecol 95(5):688–691

Upson K, Missmer SA (2020) Epidemiology of denomyosis. Semin Reprod Med 38(2–03):89–107

Miyagawa C, Murakami K, Tobiume T, Nonogaki T, Matsumura N (2021) Characterization of patients that can continue conservative treatment for adenomyosis. BMC Women’s Health 21(1):431

Deblaere L, Froyman W, van den Bosch T, van Rompuy AS, Kaijser J, Deprest J, Timmerman D (2019) Juvenile cystic adenomyosis: a case report and review of the literature. Australas J Ultrasound Med 22(4):295–300

Dogan E, Gode F, Saatli B, Secil M (2008) Juvenile cystic adenomyosis mimicking uterine malformation: a case report. Arch Gynecol Obstet 278(6):593–595

Vlahos NF, Theodoridis TD, Partsinevelos GA (2017) Myomas and adenomyosis: impact on reproductive outcome. BioMed Res Int 2017:5926470

Struble J, Reid S, Bedaiwy MA (2016) Adenomyosis: a clinical review of a challenging gynecologic condition. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 23(2):164–185

Casadio P, Raffone A, Maletta M, Travaglino A, Raimondo D, Raimondo I, Santoro A, Paradisi R, Zannoni GF, Mollo A, Seracchioli R (2021) Clinical characteristics of patients with endometrial cancer and adenomyosis. Cancers 13(19):4918

Sharara FI, Kheil MH, Feki A, Rahman S, Klebanoff JS, Ayoubi JM, Moawad GN (2021) Current and prospective treatment of adenomyosis. J Clin Med 10(15):3410

Huang R, Li X, Jiang H, Li Q (2022) Barriers to self-management of patients with adenomyosis: a qualitative study. Nurs Open 9(2):1086–1095

Kitawaki J (2006) Adenomyosis: the pathophysiology of an estrogen-dependent disease. Best Pract Res Clin Obstetr Gynaecol 20:493–502

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Br Med J 339:b2700

Vannuccini S, Petraglia F (2019) Recent advances in understanding and managing adenomyosis. F1000Research 8:283

McCausland AM (1992) Hysteroscopic myometrial biopsy: its use in diagnosing adenomyosis and its clinical application. Am J Obstet Gynecol 166(6):1619–1628

Di Spiezio Sardo A, Calagna G, Santangelo F, Zizolfi B, Tanos V, Perino A, De Wilde RL (2017) The role of hysteroscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of adenomyosis. BioMed Res Int 2017:2518396

Graziano A, Lo Monte G, Piva I, Caserta D, Karner M, Engl B, Marci R (2015) Diagnostic findings in adenomyosis: a pictorial review on the major concerns. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 19(7):1146–1154

Dakhly D, Abdel Moety G, Saber W, Gad Allah S, Hashem A, Abdel Salam L (2016) Accuracy of hysteroscopic endomyometrial biopsy in diagnosis of adenomyosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 23(3):364–371

Brosens JJ, Barker FG (1995) The role of myometrial needle biopsies in the diagnosis of adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 63(6):1347–1349

Cherng-Jye J, Shih-Hung H, Jenta Sh, Chun-Shan Ch, Chii-Ruey Tz (2007) Laparoscopy-guided myometrial biopsy in the definite diagnosis of diffuse adenomyosis. Hum Reprod 22(7):2016–2019

Krentel H, Cezar C, Becker S, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Tanos V, Wallwiener M, De Wilde RL (2017) From clinical symptoms to mr imaging: diagnostic steps in adenomyosis. BioMed Res Int 2017:1514029

Di Donato N, Bertoldo V, Montanari G, Zannoni L, Caprara G, Seracchioli R (2015) Question mark form of uterus: a simple sonographic sign associated with the presence of adenomyosis. Obstet Gynecol Int 46(1):126–127

Habiba M, Benagiano G (2021) Classifying adenomyosis: progress and challenges. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(23):12386

Decter D, Arbib N, Markovitz H, Seidman DS, Eisenberg VH (2021) Sonographic signs of adenomyosis in women with endometriosis are associated with infertility. J Clin Med 10(11):2355

Rasmussen CK, Hansen ES, Ernst E, Dueholm M (2019) Two- and three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasonography for diagnosis of adenomyosis of the inner myometrium. Reprod Biomed Online 38(5):750–760

Vandermeulen L, Cornelis A, Rasmussen CK, Timmerman D, van den Bosch T (2017) Guiding histological assessment of uterine lesions using 3D in vitro ultrasonography and stereotaxis. Facts Views Vision Obstetr Gynaecol 9(2):77–84

Sharma K, Bora MK, Venkatesh BP, Barman P, Roy SK, Jayagurunathan U, Sellamuthu E, Moidu F (2015) Role of 3D ultrasound and doppler in differentiating clinically suspected cases of leiomyoma and adenomyosis of uterus. J Clin Diagn Res 9(4):8–12

Săsăran V, Turdean S, Gliga M, Ilyes L, Grama O, Muntean M, Pușcașiu L (2021) Value of strain-ratio elastography in the diagnosis and differentiation of uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. J Personal Med 11(8):824

Stamatopoulos CP, Mikos T, Grimbizis GF, Dimitriadis AS, Efstratiou I, Stamatopoulos P, Tarlatzis BC (2012) Value of magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis of adenomyosis and myomas of the uterus. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 19(5):620–626

Bazot M, Cortez A, Darai E, Rouger J, Chopier J, Antoine JM, Uzan S (2001) Ultrasonography compared with magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: correlation with histopathology. Hum Reprod 16(11):2427–2433

Xu T, Li Y, Jiang L, Liu Q, Liu K (2022) Subserous cystic adenomyosis: a case report and review of the literature. Front Surg 9:807676

Arya S, Burks HR (2021) Juvenile cystic adenomyoma, a rare diagnostic challenge: case reports and literature review. Fertil Steril Rep 2(2):166–171

Wong S, Ray CE (2022) Adenomyosis—an overview. Semin Interv Radiol 39(1):119–122

Kho KA, Chen JS, Halvorson LM (2021) Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of adenomyosis. J Am Med Assoc 326(2):177–178

Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, Proctor M (2015) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015(7):CD001751

Szubert M, Koziróg E, Olszak O, Krygier-Kurz K, Kazmierczak J, Wilczynski J (2021) Adenomyosis and infertility-review of medical and surgical approaches. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(3):1235

Maia H, Maltez A, Coelho G, Athayde C, Coutinho EM (2003) Insertion of mirena after endometrial resection in patients with adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 10:512–516

Ozdegirmenci O, Kayikcioglu F, Akgul MA, Kaplan M, Karcaaltincaba M, Haberal A, Akyol M (2011) Comparison of levonorgestrel intrauterine system versus hysterectomy on efficacy and quality of life in patients with adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 95:497–502

Sheng J, Zhang WY, Zhang JP, Lu D (2009) The LNG-IUS study on adenomyosis: a 3-year follow-up study on the efficacy and side effects of the use of levonorgestrel intrauterine system for the treatment of dysmenorrhea associated with adenomyosis. Contraception 79(3):189–193

Zhang L, Yang H, Zhang X, Chen Z (2019) Efficacy and adverse effects of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system in treatment of adenomyosis. J Zhejiang Univ Med Sci 48(2):130–135

Vannuccini S, Luisi S, Tosti C, Sorbi F, Petraglia F (2018) Role of medical therapy in the management of uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 109(3):398–405

Ota H, Maki M, Shidara Y, Kodama H, Takahashi H, Hayakawa M, Fujimori R, Kushima T, Ohtomo K (1992) Effects of danazol at the immunologic level in patients with adenomyosis, with special reference to autoantibodies: a multi-center cooperative study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 167(2):481–486

Igarashi M (1990) A new therapy for pelvic endometriosis and uterine adenomyosis: local effect of vaginal and intrauterine danazol application. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol 16(1):1–12

Friend DR (2017) Drug delivery for the treatment of endometriosis and uterine fibroids. Drug Deliv Transl Res 7(6):829–839

Luisi S, Razzi S, Lazzeri L, Bocchi C, Severi FM, Petraglia F (2009) Efficacy of vaginal danazol treatment in women with menorrhagia during fertile age. Fertil Steril 92(4):1351–1354

Tosti C, Vannuccini S, Troìa L, Luisi S, Centini G, Lazzeri L, Petraglia F (2017) Long-term vaginal danazol treatment in fertile age women with adenomyosis. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Adenomyosis 9(1):39–43

Yang R, Guan Y, Perrot V, Ma J, Li R (2021) Comparison of the long-acting GnRH agonist follicular protocol with the GnRH antagonist protocol in women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv Ther 38(5):2027–2037

Grow DR, Filer RB (1991) Treatment of adenomyosis with long-term GnRH analogues: a case report. Obstet Gynecol 78(3):538–539

Donnez J, Taylor RN, Taylor HS (2017) Partial suppression of estradiol: a new strategy in endometriosis management? Fertil Steril 107(3):568–570

Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, Abrao MS, Kotarski J, Archer DF, Diamond MP, Surrey E, Johnson NP, Watts NB, Gallagher JC, Simon JA, Carr BR, Dmowski WP, Leyland N, Rowan JP, Duan WR, Pharm JD, Schwefel B, Thomas JW, Jain RI, Chwalisz K (2017) Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N Engl J Med 377:28–40

Kimura F, Takahashi K, Takebayashi K, Fujiwara M, Kita N, Noda Y, Harada N (2007) Concomitant treatment of severe uterine adenomyosis in a premenopausal woman with an aromatase inhibitor and a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist. Fertil Steril 87(6):e9–e12

Shrestha A, Shrestha R, Sedhai LB, Pandit U (2012) Adenomyosis at hysterectomy: prevalence, patient characteristics, clinical profile and histopathological findings. Kathmandu Univ Med J 10(37):53–56

Stovall TG, Summitt RL (1996) Laparoscopic hysterectomy—is there a benefit? N Engl J Med 335(7):512–513

Munro MG (2018) Endometrial ablation. Best practice and research. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 46:120–139

McCausland V, McCausland A (1998) The response of adenomyosis to endometrial ablation/resection. Hum Reprod Update 4(4):350–359

Dueholm M (2018) Minimally invasive treatment of adenomyosis. Best practice and research. Clin Obstet Gynaecol 51:119–137

de Bruijn A, Smink M, Hehenkamp W, Nijenhuis RJ, Smeets AJ, Boekkooi F, Reuwer P, van Rooij WJ, Lohle P (2017) Uterine artery embolization for symptomatic adenomyosis: 7-year clinical follow-up using UFS-Ool questionnaire. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 40(9):1344–1350

Wang P, Liu WM, Fuh JL, Cheng MH, Chao HT (2009) Comparison of surgery alone and combined surgical-medical treatment in the management of symptomatic uterine adenomyoma. Fertil Steril 92(3):876–885

Taran FA, Stewart EA, Brucker S (2013) Adenomyosis: epidemiology, risk factors, clinical phenotype and surgical and interventional alternatives to hysterectomy. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 73(9):924–931

Wood C, Maher P, Hill D (1994) Biopsy diagnosis and conservative surgical treatment of adenomyosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 1(4):313–316

Nishida M, Takano K, Arai Y, Ozone H, Ichikawa R (2010) Conservative surgical management for diffuse uterine adenomyosis. Fertil Steril 94(2):715–719

Gao Y, Shan S, Zhao X, Jiang J, Li D, Shi B (2019) Clinical efficacy of adenomyomectomy using “H” type incision combined with Mirena in the treatment of adenomyosis. Medicine 98(11):e14579

Nishida M, Ichikawa R, Arai Y, Sakanaka M, Otsubo Y (2014) New myomectomy technique for diffuse uterine leiomyomatosis. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 40(6):1689–1694

Cheung VY (2017) Current status of high-intensity focused ultrasound for the management of uterine adenomyosis. Ultrasonography 36(2):95–102

Fukunishi H, Funaki K, Sawada K, Yamaguchi K, Maeda T, Kaji Y (2008) Early results of magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound surgery of adenomyosis: analysis of 20 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 15(5):571–579

Shui L, Mao S, Wu Q, Huang G, Wang J, Zhang R, Li K, He J, Zhang L (2015) High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for adenomyosis: two-year follow-up results. Ultrason Sonochem 27:677–681

Kowalik A, Zalewski K, Kopczynski J, Siolek M, Lech M, Hincza K, Kalisz J, Chrapek M, Zieba S, Furmanczyk O, Jedlinski M, Chlopek M, Misiek M, Gozdz S (2019) Somatic mutations in BRCA1 and 2 in 201 unselected ovarian carcinoma samples - single institution study. Polish J of Pathol 70(2):115–126

Funding

The author declares that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RSM: project development, data collection, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

IRB ethical approval

This study did not require ethics approval, since the research does not involve human participants and/or animals.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Moldassarina, R.S. Modern view on the diagnostics and treatment of adenomyosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 308, 171–181 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-06982-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-023-06982-1