Abstract

Purpose

Sexual violence is a global health problem. We aimed to evaluate the association between self-reported history of sexual violence and parturients’ health behaviors, focusing on routine gynecological care, and mental well-being.

Methods

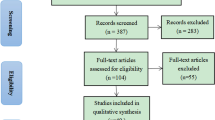

This was a retrospective questionnaire-based study, including mothers of newborns delivered at the “Soroka” University Medical Center (SUMC). Participants were asked to complete three validated questionnaires, including: screening for sexual violence history (SES), post-traumatic stress disorder (PDS) and post-partum depression (EPDS). Additionally, a demographic, pregnancy and gynecological history data questionnaire was completed, and medical record summarized. Multiple analyses were performed, comparing background and outcome variables across the different SES severity levels. Multivariable regression models were constructed, while adjusting for confounding variables.

Results

The study included 210 women. Of them, 26.3% (n = 57) reported unwanted sexual encounter, 23% (n = 50) reported coercion, 1.8% (n = 4) assault and attempted rape, and 1.4% (n = 3) reported rape. A significant association was found between sexual violence history and neglected gynecological care, positive EPDS screening, and reporting experiencing sexual trauma. Several multivariable regression models were constructed, to assess independent associations between sexual violence history and gynecological health-care characteristics, as well as EPDS score. Sexual violence history was found to be independently and significantly associated with a negative relationship with the gynecologist, avoidance of gynecological care, sub-optimal routine gynecological follow-up, and seeking a gynecologist for acute symptoms (adjusted OR = 0.356; 95% CI 0.169–0.749, adjusted OR = 0.369; 95% CI 0.170–0.804, adjusted OR = 2.255; 95% CI 1.187–4.283, and adjusted OR = 2.113; 95% CI 1.085–4.111, respectively), as well as with the risk of post-partum depression (adjusted OR = 4.46; 95% CI 2.03–9.81). All models adjusted for maternal age and ethnicity.

Conclusion

Sexual violence history is extremely common among post-partum women. It is independently associated with post-partum depression, neglected gynecological care, a negative relationship with the gynecologist, and with reporting of experiencing sexual trauma. Identifying populations at risk and taking active measures, may reduce distress and improve emotional well-being and family function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sexual violence is a significant and global public health problem, occurring daily throughout the world [1, 2]. It is defined by the World Health Organization as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, as well as unwanted sexual comments or advances. Sexual violence also includes acts to traffic or acts directed against a person’s sexuality regardless of their relationship to the victim, and in any setting [1]. The perpetrators may be spouses, partners, parents or other family members, neighbors, and people in positions of power or influence and in most cases are known to the victim. In a minority of cases the perpetrator is unknown to the victim. In many cases female victims experience repeated incidents over a course of years and decades [3]. Sexual violence is far more prevalent in daily life in most societies than is usually suspected. In some countries nearly one in four women experience sexual violence by an intimate partner, and up to one-third of adolescent girls report their first sexual experience as being forced [1]. Roughly 35% of women worldwide have experienced physical and/or sexual violence [4] and a quarter of girls worldwide are exposed to some form of sexual abuse during childhood [5]. Lack of trust in the social systems, shame, social definitions of sexual assault, impaired cognitive processing, and the victim/offender relationship, may be some of the reasons for substantial under-reporting [6]. In Israel, data from 2016 published by the Central Bureau of Statistics Israel (CBS) show that more than 3.8% of Israeli women over the age 20 have been victims of sexual violence. The annual report of the Association of Rape Crisis Centers in Israel (ARCCI) in 2018 reported that only 17.2% of the victims contacted help centers that year, and only 3.2% of sexual assaults were reported to the police. According to the Ministry of public security of Israel, in their latest National Violence Index published in 2014 [7], it is estimated that one of three women will be sexually assaulted throughout life. An Israeli research on women between ages 16–28 discovered that 33% were physically sexually assaulted and 21% of the women reported they were raped [8]. This is similar to the prevalence reported by the WHO and the CDC [4, 9], and higher than the Organization for Economic Co- operation and Development (OECD) countries, reported rate of sexual assaults [10, 11]. Women who have suffered prior sexual assault are at increased risk for psychological, physical, and behavioral adverse effects. The consequences may be immediate and/or long-term, related to reproductive as well as mental health, and social well-being [1, 12, 13]. Consequences may include (but are not limited to) pregnancy and gynecological complications, sexually transmitted diseases, decreased sexual satisfaction and dyspareunia [1, 3, 14,15,16,17,18,19].

The significance of periodic gynecological assessments and the positive effect of prenatal care on pregnancy outcomes are well established. Annual gynecological examinations are a fundamental part of medical health care in Israel and are valuable in promoting prevention practices, recognizing risk factors for disease, identifying medical problems, and establishing a clinician–patient relationship [20]. Prenatal care allows early recognition and treatment of maternal and fetal health related problems, thus increasing the chances for an uncomplicated pregnancy, and delivery of a healthy newborn [21, 22]. Data establishing an association between maternal history of sexual violence and later gynecological health is scarce. Published data is mostly focused on specific aspects of obstetrical care [23, 24], where women were recruited after voluntarily seeking help [25, 26], and some were not specifically sexually abused [27]. Other studies focused only on childhood sexual abuse [28,29,30]. Postpartum depression is a common and significant pregnancy related risk, in Israel and worldwide [31], which has been associated with sexual violence [32,33,34]. We aimed to evaluate the association between history of sexual violence and parturients’ mental well-being and health behaviors, with a focus on compliance with routine gynecological care recommended practices, and on post-partum depression.

Materials and methods

Design

This was a retrospective study, in which women delivering a live singleton newborn at the “Soroka” University Medical Center (SUMC) from October 2018 to February 2019 were included. Our study population was composed of two main ethnic groups: Bedouin and Jewish. The Bedouin are a minority group (~ n = 200,000) residing in southern Israel. This society is in cultural transition while attempting to preserve its traditional values and lifestyle. Most of the Bedouin women marry at a young age; some live in polygamous consanguineous marriages and have higher parity [35]. About 75% of Israel’s population identifies as being Jewish. This Jewish population is largely an immigrant society that derives from multiple ethnic origins, mainly from northern Africa and eastern Europe. Their religiosity varies from extremely orthodox, traditional to completely secular. Their fertility rate is higher than in any other developed country [36].

SUMC is the only tertiary medical center in the region, and both ethnicities included in the study populations rely heavily on it for their healthcare. SUMC has the largest birth center in Israel, with roughly 17,000 births per year. Approximately half of the deliveries are of Bedouin origin and half Jewish [37]. Israeli health-care law allows all citizens equal access to all public health-care facilities with all medical expenses covered, including prenatal visits.

The study was approved by the local institutional ethical review board (SUMC IRB).

Instruments

Participants were asked to answer a total of 4 self-completed questionnaires, including screening for sexual violence history, post-traumatic stress disorder, and post-partum depression, as well as demographic, pregnancy and gynecological history data. These questionnaires included:

-

1.

Sexual Experiences Survey (SES)- a self-reporting questionnaire that assesses victimization of unwanted sexual encounters by 4 levels of severity, with 13 yes/no questions. (Question 1- no victimization, Questions 2–6- coercion, Questions 7–9- assault and attempted rape, Questions 10–13- rape) Answering any of Questions 2–13 positively refers to an unwanted sexual encounter [38].

-

2.

Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS)- a self-reported measure of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) for use in both clinical and research settings [39], that corresponds to the DSM –V for PTSD.

The respondents are asked to checkmark any traumatic events they have experienced and/or witnessed, to specify the main trauma and briefly describe the traumatic event. They are asked to mark disturbances they experience, the frequency and duration of them, and report clinically significant distress or impairment in important areas of functioning. The Symptom Severity Score ranges from mild to severe.

-

3.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)- A 10-question self-rating scale validated for screening for perinatal depression. The maximum score is 30 and possible depression is suggested at a score of 10 or more [40].

-

4.

Demographic, pregnancy and gynecological history data- a three parts, self-reporting questionnaire.

Procedure

Participants were approached during the post-partum hospitalization period. Illiterate Women, women who delivered multiples, and women who did not provide oral and written consent to participate in the study were not included. Those who expressed initial interest, received an explanation regarding the study and read the explanatory leaflet. Parturients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate, provided a written informed consent, and completed the above-mentioned questionnaires. In addition, their medical records were reviewed.

Body Mass Index (BMI)—was calculated by weight/height2, and divided in three groups, normal or low (BMI < 25), overweight (BMI of 25–30) and obese (BMI > 30).

Level of education was assessed by elementary, high school, academic and none.

Analysis

The study population was divided into two main groups according to the Sexual Experiences Survey (SES) level: parturients scoring 2–4 on the SES were defined as the exposed group, and the comparison group (unexposed group) represented women who reported no victimization (level 1 on the SES).

All analyses were performed using SPSS software version 23.0.

Multiple analyses were performed, comparing background and outcome variables across all 4 levels of SES severity (scores 1–4), using ANOVA and Chi-square tests. Additionally, the entire exposed group was compared to the unexposed group, using Chi-square and t-tests (2–4). Multivariable logistic regression models were constructed to examine the relationship between exposure to victimization of any unwanted sexual encounters, based on the SES scores (SES = 2–4 were defined as exposed; SES = 1 were defined as unexposed) and the dependent variables: EPDS score, relationship with their gynecologist, reason for gynecological visits, routine gynecology care, and avoidance of gynecological visits. The regression models adjusted for confounding variables including – maternal age, ethnicity and maternal education, based on the univariable analysis.

Results

During the study period, 210 women met the inclusion criteria, while 4 women were excluded due to multiple gestation. Of them, 57 (27.1%) reported unwanted sexual encounter victimization, 50 (23.8%) reported coercion, 4 (1.9%) assault and attempted rape, and 3 (1.4%) reported they were raped.

Table 1 presents a comparison of demographic characteristics among all 4 levels of sexual violence severity. No significant association was found between age or ethnicity and personal history of sexual violence. Women who reported sexual violence belonged more often to the category with normal or low (< 25) BMI (p = 0.003) and were more likely to report smoking (p = 0.045). An association between a history of sexual violence and level of education was also demonstrated (p = 0.013). In the exposed group, a higher rate of women with academic education was found, and in the unexposed group there were more women with high school education only.

Table 2 presents a comparison of gynecological and obstetrical background among all 4 levels of sexual violence severity. No association was found between parity or a history of cesarean sections and sexual violence history. Women who were exposed to sexual violence experienced significantly more abortions (spontaneous/induced, p = 0.023).

More exposed women stated that they avoided gynecological visits (29.1% versus 14.3%, p = 0.016) and less attended routine gynecological follow-ups (49.1% versus 69%, p = 0.002). If exposed women did see a gynecologist, it was more likely due to an acute symptom as compared to the unexposed (45.3% versus 27.1%, p = 0.024).

The relationship with the gynecologist exhibited a significant association with sexual violence history, and more women in the exposed group described it as awkward or negative, as compared to the unexposed group (33.9% versus 16.7%, p = 0.012). Most of the women in the sample felt they could trust their gynecologist (93.8%), but for different reasons: in the exposed group it was due to positive communication (57.1%), while in the unexposed group the main reason was professionality (51.4%) however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. Both groups preferred a female gynecologist (93.3% and 86.7%, in exposed and unexposed, respectively). Exposed women needed significantly less pain control during labor (p = 0.004).

Table 3 demonstrates a significant association between positive screening for postnatal depression (EPDS ≥ 10) and sexual violence history (p = 0.001). In the PDS questionnaire, which measures post-traumatic stress, a significantly higher portion of the exposed group reported experiencing and/or witnessing sexual trauma (14.3% versus 2%, p = 0.002).

According to the performed multivariate regression models, as seen in Table 4, sexual violence history was found to be independently and significantly associated with the risk for post-partum depression while adjusting for maternal age, ethnicity, and maternal education (adjusted OR = 4.46; 95% CI 2.03–9.81, p < 0.001). In addition, sexual violence history was found to be associated with a negative relationship with the gynecologist, seeking a gynecologist for acute symptoms, attending less routine gynecological follow-ups, and avoidance of gynecological visits in general. These models were adjusted for maternal age and ethnicity (adjusted OR = 0.356; 95%CI 0.169–0.749, p = 0.006, adjusted OR = 2.113; 95%CI 1.085–4.111, p = 0.028, adjusted OR = 2.255; 95%CI 1.187–4.283, p = 0.013, adjusted OR = 0.369; 95%CI 0.170–0.804, p = 0.012, respectively).

Discussion and conclusions

Main findings

The main finding of this study is that within post-partum women, a history of sexual violence is common and is independently associated with a higher risk for post-partum depression (according to the EPDS screening) and also with reporting sexual trauma. Additionally, we found a significant and complex association with gynecological care.

The prevalence of sexual violence in post-partum women

The number of post-partum women reporting sexual violence in our study was very high but in agreement with previous worldwide publications [1, 4]. Over a quarter of the current sample (27.1%) reported a history of unwanted sexual encounter victimization. This rate is even higher than previously published data [23], and probably reflects that all the disturbing adverse effects that history of sexual violence is known to be associated with (psychological, physical, and behavioral) are relevant to pregnant and post-partum women.

Post-partum depression and reported sexual trauma

Among mothers with sexual violence history the risk for post-partum depression was nearly 4.5 greater than in unexposed mothers. As post-partum depression is one of the most frequent complications of childbirth and is associated with many adverse outcomes for both mother and offspring, it is, thus, important to asses any history of sexual violence. Other studies show similar findings; history of childhood sexual abuse [32], intimate partner violence and sexual violence as a part of it [33], or any violence including sexual violence [34] have been previously shown to be associated with post-partum depression. Adverse life events, like sexual violence, are known to be a strong predictor of the disorder [31]. Another important finding was that 14.3% of exposed women reported experiencing and/or witnessing sexual trauma as opposed to 2% in the unexposed group. Post-partum depression and post-partum PTSD overlap and affect one another [41]. Published data suggests that pregnancy and birth increase the risk of adverse mental health conditions, leading to bonding impairment [42].

Routine gynecological care

Routine gynecological visits are invaluable. Gynecologists have an opportunity to contribute to the overall health and well-being of women, providing recommended preventive services, screening, evaluation and counseling, and immunizations based on age and risk factors [20]. In the current study, there was a significant association between sexual violence history and frequency of gynecological visits. As many as 29.1% of exposed women reported avoiding these visits, and only 49.1% followed up with the recommended routine visits. This finding can relate to the association found between prior exposure to sexual violence, PTSD and higher rates of distress and pain associated with the pelvic examination [19]. The gynecological examination might evoke memories of the abuse and cause anxiety, distress and consequently an overall feeling of discomfort [43]. These feelings may also account for our findings that a higher percentage of the exposed group described their relationship with their gynecologist as awkward and negative, and that a significant percentage of their visits were for acute problems, rather than the recommended routine visits. Women who defined their emotional communication with health professionals as negative are more likely to feel extreme discomfort during vaginal examinations [44]. Several studies have shown that sexually assaulted women have a poor perception of health and seek medical care more frequently [14, 45, 46]. However, other studies show victims of sexual trauma to be less likely than other women to obtain regular cervical cancer screenings, and to submit to regular pelvic exams [47, 48].

Ethnicity

Ethnicity has a significant influence on the risk for post-partum depression. In our sample, Bedouin women were almost 3 times more likely to suffer from post-partum depression, as compared to Jewish women. An astonishing rate of 75% of exposed Bedouin women were at risk of post-partum depression. The fact that Bedouin women are at a great risk of post-partum depression is supported by previous publications [49].

Limitations and strengths

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, our findings are based on a self-report questionnaire focused on highly sensitive and personal information, and as such may be influenced by factors such as miss-interpretation and family members or other people who were present and may have influenced the answers. Nevertheless, in most cases, the woman was alone while approached. Furthermore, religion, culture, possible embarrassment and fear could have affected sincerity. Additionally, timing may have had an effect, as having just given birth, tiredness, breastfeeding and caring for the newborn may have impacted maternal mood and answers. However, the study team, Hebrew and Arabic speaking members providing easy accessibility to all ethnical groups, tried to approach the patients in the best setting possible and usually in a private setting, during the same post-partum period (24–48 h).

Strengths of our study include use of reliable and validated tools for the evaluation of maternal history of sexual violence, post-partum depression and PTSD, and reached significant results, usually consistent with previously published data. The associations observed between self-reported history of sexual violence and women's health behaviors, mental health, relationship with gynecologist and routine gynecological care, shed additional light on the issue surrounding sexual violence, thereby helping us to understand mechanisms affecting women’s health, that deserve immediate attention and even lifesaving intervention.

Conclusions

Sexual violence history is unfortunately extremely common among post-partum women and appears to be independently and significantly associated with neglected gynecological care, a negative relationship with the gynecologist, and post-partum depression. It is also significantly associated with reporting of sexual trauma. Therefore, we feel it is crucial for health-care providers to ask every woman about history of sexual violence, be alert to populations at risk, and use this knowledge to provide individually adjusted care. The risk for post-partum depression is also affected by sexual violence history. As practiced in many countries, all pregnant women should be screened for post-partum depression, and in particular those who report sexual violence history. Active measures focused on populations at risk, may reduce distress and improve emotional well-being and family function. Routine prenatal care is the period in which women are frequently seen by health-care professionals and a unique window of opportunity to detect those who were sexually hurt, particularly as we know they are psychiatrically vulnerable.

Sexual violence has not been sufficiently researched, and in light of our findings, its impact on women’s health care, emotional well-being, and associated factors, should be further investigated alongside interventional programs.

Data availability

All are available.

References

Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R (2002) World report on violence and health. World Health Organization, Geneva

Garcia-Moreno C, Zimmerman C, Morris-Gehring A, Heise L, Amin A, Abrahams N et al (2015) Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet 385(9978):1685–1695

Tavara L (2006) Sexual violence. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 20(3):395–408

Garcia-Moreno C, Pallitto C, Devries K, Stöckl H, Watts C, Abrahams N et al (2013) Global and regional estimates of violence against women. World Health Organization, Italy

Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S (2009) Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet 373(9657):68–81

Jones JS, Alexander C, Wynn BN, Rossman L, Dunnuck C (2009) Why women don’t report sexual assault to the police: the influence of psychosocial variables and traumatic injury. J Emerg Med 36(4):417–424

Ministry of public security of Israel (2014) National Violence Index.

Moor A (2009) Prevalence of exposure to sexual violence among women in Israel: preliminary assessment. Social Issues Israel 7:46–65

Black MC, Basile KC, Breiding MJ, Smith SG, Walters ML, Merrick MT, Chen J, Stevens MR (2011) The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta

OECD (2011) Compendium of OECD Well-Being Indicators. OECD

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2011) PRINCIPLES AND FRAMEWORK FOR AN INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF CRIMES FOR STATISTICAL PURPOSES REPORT OF THE UNODC/UNECE TASK FORCE ON CRIME CLASSIFICATION

Belik SL, Stein MB, Asmundson GJ, Sareen J (2009) Relation between traumatic events and suicide attempts in Canadian military personnel. Can J Psychiatry 54(2):93–104

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) (2018) Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia. AIHW, Canberra

Jina R, Thomas LS (2013) Health consequences of sexual violence against women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 27(1):15–26

Sharman LS, Douglas H, Price E, Sheeran N, Dingle GA (2018) Associations between unintended pregnancy, domestic violence, and sexual assault in a population of Queensland women. Psychiatr Psychol Law 26(4):541–552

Mark H, Bitzker K, Klapp BF, Rauchfuss M (2008) Gynaecological symptoms associated with physical and sexual violence. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 29(3):164–172

McCall-Hosenfeld JS, Liebschutz JM, Spiro A, Seaver MR (2009) Sexual assault in the military and its impact on sexual satisfaction in women veterans: a proposed model. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 18(6):901–909

Chen LP, Murad MH, Paras ML, Colbenson KM, Sattler AL, Goranson EN et al (2010) Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 85(7):618–629

Weitlauf JC, Finney JW, Ruzek JI, Lee TT, Thrailkill A, Jones S, Frayna SM (2008) Distress and pain during pelvic examinations: effect of sexual violence. Obstet Gynecol 112(6):1343–1350

ACOG Committee (2018) ACOG committee opinion No. 755: well-woman visit. Obstetrics Gynecol 132(4):1084–1085

Kirkham C, Harris S, Grzybowski S (2005) Evidence-based prenatal care: part I. General prenatal care and counseling issues. Am Fam Physician 71(7):1307–1316

Kirkham C, Harris S, Grzybowski S (2005) Evidence-based prenatal care: part II. Third-trimester care and prevention of infectious diseases. Am Fam Physician 71(8):1555–1560

Lukasse M, Henriksen L, Vangen S, Schei B (2012) Sexual violence and pregnancy-related physical symptoms. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12:83

Henriksen L, Schei B, Vangen S, Lukasse M (2014) Sexual violence and mode of delivery: a population-based cohort study. BJOG 121(10):1237–1244

Gisladottir A, Harlow BL, Gudmundsdottir B, Bjarnadottir RI, Jonsdottir E, Aspelund T et al (2014) Risk factors and health during pregnancy among women previously exposed to sexual violence. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 93(4):351–358

Gisladottir A, Luque-Fernandez MA, Harlow BL, Gudmundsdottir B, Jonsdottir E, Bjarnadottir RI et al (2016) Obstetric outcomes of mothers previously exposed to sexual violence. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0150726

Rich-Edwards JW, James-Todd T, Mohllajee A, Kleinman K, Burke A, Gillman MW, Wright RJ (2011) Lifetime maternal experiences of abuse and risk of pre-natal depression in two demographically distinct populations in Boston. Int J Epidemiol 40(2):375–384

Leeners B, Stiller R, Block E, Gorres G, Rath W (2010) Pregnancy complications in women with childhood sexual abuse experiences. J Psychosom Res 69(5):503–510

Leeners B, Stiller R, Block E, Gorres G, Rath W, Tschudin S (2013) Prenatal care in adult women exposed to childhood sexual abuse. J Perinat Med 41(4):365–374

Yampolsky L, Lev-Wiesel R, Ben-Zion IZ (2010) Child sexual abuse: is it a risk factor for pregnancy? J Adv Nurs 66(9):2025–2037

Guintivano J, Manuck T, Meltzer-Brody S (2018) Predictors of postpartum depression: a comprehensive review of the last decade of evidence. Clin Obstet Gynecol 61(3):591–603

Wosu AC, Gelaye B, Williams MA (2015) History of childhood sexual abuse and risk of prenatal and postpartum depression or depressive symptoms: an epidemiologic review. Arch Womens Ment Health 18(5):659–671

Rogathi JJ, Manongi R, Mushi D, Rasch V, Sigalla GN, Gammeltoft T et al (2017) Postpartum depression among women who have experienced intimate partner violence: a prospective cohort study at Moshi, Tanzania. J Affect Disord 218:238–245

Wu Q, Chen HL, Xu XJ (2012) Violence as a risk factor for postpartum depression in mothers: a meta-analysis. Arch Womens Ment Health 15(2):107–114

Merrick J, Al-Krenawi A, Elbedour S (2013) Bedouin Health: perspectives from Israel. Nova Biomedical, New York

DellaPergola S (2016) World Jewish Population, 2015. In: Dashefsky A, Sheskin I (eds) American Jewish Year Book 2015. American Jewish Year Book, vol 115. Springer, Cham

Stavsky M, Robinson R, Sade MY, Krymko H, Zalstein E, Ioffe V, Novack V, Levitas A (2017) Elevated birth prevalence of conotruncal heart defects in a population with high consanguinity rate. Cardiol Young 27(1):109–116

Koss MP, Oros CJ (1982) Sexual Experiences Survey: a research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. J Consult Clin Psychol 50(3):455–457

Foa EB, Cashman L, Jaycox L, Perry K (1997) The validation of a self-report measure of posttraumatic stress disorder: the posttraumatic diagnostic scale. Psychol Assess 9(4):445–451

Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R (1987) Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psychiatry 150:782–786

Grekin R, O’Hara MW (2014) Prevalence and risk factors of postpartum posttraumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 34(5):389–401

Seng JS, Sperlich M, Low LK, Ronis DL, Muzik M, Liberzon I (2013) Childhood abuse history, posttraumatic stress disorder, postpartum mental health, and bonding: a prospective cohort study. J Midwifery Womens Health 58(1):57–68

Hilden M, Sidenius K, Langhoff-Roos J, Wijma B, Schei B (2003) Women’s experiences of the gynecologic examination: factors associated with discomfort. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 82(11):1030–1036

Güneş G, Karaçam Z (2017) The feeling of discomfort during vaginal examination, history of abuse and sexual abuse and post-traumatic stress disorder in women. J Clin Nurs 26(15–16):2362–2371

Resnick HS, Acierno R, Kilpatrick DG (1997) Health impact of interpersonal violence. 2: medical and mental health outcomes. Behav Med 23(2):65–78

Golding JM, Cooper ML, George LK (1997) Sexual assault history and health perceptions: seven general population studies. Health Psychol 16(5):417–425

Tsai J (2019) Resistance and surrender—remembering to bow to strength. Not Power N Engl J Med 380(5):412–413

Cadman L, Waller J, Ashdown-Barr L, Szarewski A (2012) Barriers to cervical screening in women who have experienced sexual abuse: an exploratory study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care 38(4):214–220

Mazor E, Sheiner E, Wainstock T, Attias M, Walfisch A (2019) The association between depressive state and maternal cognitive function in postpartum women. Am J Perinatol 36(3):285–290

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TR: Project development, Data Collection, Data management, Data analysis, Manuscript writing. AW: Project development, Data analysis, Manuscript editing. ES: Project development, Manuscript editing. LAE: Data Collection. SZ: Data Collection. AA: Data Collection. TW: Data analysis, Manuscript editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the local institutional ethical review board (SUMC IRB).

Consent to participate

All women provided oral and written consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Razi, T., Walfisch, A., Sheiner, E. et al. #metoo? The association between sexual violence history and parturients’ gynecological health and mental well-being. Arch Gynecol Obstet 304, 385–393 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-05977-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-05977-0