Abstract

Background

Epidemiological studies assessing the relationship between dietary vitamin B2 and the risk of breast cancer have produced inconsistent results. Thus, we conducted this meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies to evaluate this association.

Methods

We searched English-language MEDLINE publications and conducted a manual search to screen eligible articles. A random-effect model was used to pool study-specific risk estimates. Egger’s linear regression test was also used to detect publication bias in meta-analysis.

Results

In our meta-analysis, ten studies comprising totally 12,268 breast cancer patients were available in the analyses. Pooled relative risk (RR) comparing the highest to the lowest vitamin B2 intake and breast cancer incidence was 0.85 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.76–0.95]. No significant heterogeneity existed across the studies (P = 0.086, I 2 = 40.7%). No publication bias was found. The results of dose–response analysis also showed that an increment of 1 mg/day was inversely related to the risk of breast cancer (RR = 0.94; 95% CI = 0.90–0.99).

Conclusions

Results from our meta-analysis indicated that dietary vitamin B2 intake is weakly related to the reduced risk of breast cancer. Additional research is also necessary to further explore this association.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Female breast cancer is by far the most common type of cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. By 2012, approximated 1.7 million new cases of breast cancer and 521,900 related deaths were reported, accounting for 25% of all estimated new cancer cases and 15% of cancer deaths in women [1].

Epidemiology evidence has shown that reproductive factors, including a long menstrual history, nulliparity, and absence of a history of breastfeeding, might increase the risk of breast cancer [2–4]. However, the cause of this disease in the majority of cases is still obscure. There is growing evidence that some dietary factors also might exert effects on breast cancer incidence [5]. Furthermore, it is important to search for potentially dietary risk factors, because dietary habits are potentially modifiable.

One-carbon metabolism, including folate and related B vitamins, comprises a complex network of biochemical pathways that donate methyl groups for many important biological processes [6]. Dysregulation of one-carbon metabolism is believed to promote carcinogenesis [7]. Studies investigating relationship of B vitamins intake with the risk of breast cancer have mainly focused on folate. A meta-analysis of case–control studies reported a significant, protective effect of folate intake on breast cancer incidence, whereas the analysis of cohorts indicated no effects [8, 9]. Vitamin B2 (riboflavin) is an essential cofactor for a number of enzymes involved in one-carbon metabolism which might also play an important role in cancer development, including breast cancer [10].

During the last two decades, many epidemiologic studies assessed the relationship between vitamin B2 and the risk of breast cancer and produced inconsistent results. However, no systematic review and comprehensive meta-analysis evaluating this association was reported. Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis to quantitatively evaluate the relation of dietary vitamin B2 intake to the risk of breast cancer. Furthermore, we also investigated whether the association was differed by breast cancer subtype.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature was performed in MEDLINE for all relevant papers published from 1966 to January 2016. The following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and text words were used: “vitamin b2” or “riboflavin” combined with “cancer” or “neoplasm”. In addition, a hand search was conducted through checking all the references of related papers to search any additional studies. No language restrictions were imposed. Two investigators (LY and YT) performed all searches independently. When it came to discrepancy between two authors, another author was invited to discuss and check the data until a consensus was reached. The present meta-analysis was undertaken using the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) [11].

Study selection

All studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria: (1) the study had a case–control or cohort study design; (2) the exposure of interest was dietary vitamin B2 intake (i.e., vitamin B2 from foods only); (3) the outcome was breast cancer incidence/risk or mortality; and (4) the investigators provided odds ratio (OR) or relative risk (RR) with their corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) (or sufficient data to calculate them).

Data extraction

The following data were carefully extracted from the eligible studies: (1) first author’s name; (2) year of publication; (3) study design (prospective cohort study or case–control study); (4) study location; (5) years of follow-up (for prospective cohort study) or the study period; (6) characteristics of the study subjects (sample size, age range, and exclusion criteria); (7) range of exposure and risk estimates with corresponding 95% CIs; and (8) confounding factors that were controlled for by matching or adjustment. We extracted the OR or RR estimates that reflected the greatest degree of adjustment for potentially confounding variables.

The quality of study design was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for quality assessment of the nonrandomized studies [12]. A star system of NOS includes three items: patient selection, comparability of group, and assessment of outcome. A study can be awarded a maximum of one star for each item within the selection and exposure aspects and a maximum of four stars for the comparability of the two groups. Two investigators (LY and YT) independently extracted the information and evaluated study quality.

Statistical analysis

We first performed a meta-analysis comparing the highest with the lowest quantile of dietary vitamin B2 intake within the specific studies. The combined estimate was calculated as the inverse variance-weighted mean of the logarithm of risk estimate with 95% CI. Study-specific RRs were pooled using a random-effect model described by DerSimonian and Laird [13], which take into account both within-study and between-study variabilities. Furthermore, we also performed subgroup analyses stratified by study design (case–control vs. cohort), study location (Europe vs. USA), data collection (in-person interview vs. self-administrated), breast cancer phenotype (ER−, ER+), and adjustment for family history of breast cancer.

To normalize the variability among studies in the difference in categorizing vitamin B2 intake, we attempted to place the studies on a common scale by estimating the RR of 1 mg/day increase of vitamin B2 intake. The method of generalized least squares trend developed by Greenland and Longnecker [14, 15] was applied to calculate study-specific slopes and 95% CIs from the correlated natural logarithm of the RRs and CIs across dietary vitamin B2 categories. The median or midpoint of the upper and lower boundaries was assigned as the mean vitamin B2 intake in each category. If the highest category was open-ended, we assumed the width of the interval to be the same as in the closest category.

Q and I 2 statistics were used to examine heterogeneity [16]. The I 2 value ranges from 0 to 100% (the value greater than 50% was assumed as a measure of severe heterogeneity). Egger’s linear regression test was used to detect publication bias in meta-analysis [17]. To assess whether a single study could markedly affect the results, we also conduced a sensitivity analysis in which one study at a time was excluded and the remainders pooled. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 11.0 (STATA, College Station, Tex). All statistical tests were two sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Search results and study characteristics

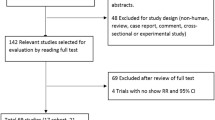

The flow of study selection was shown in Fig. 1. A total of 729 citations were yielded in the initial search, and 14 articles were reviewed in full text after the titles and abstracts reviewing. By checking reference lists, we identified one additional article. Four articles were excluded, because they investigated the relationship between other B-vitamin intake and the risk of breast cancer and there was no interest of vitamin B2 intake [18–21]. We further excluded one article that reported on similar population [22]. In the end, a total of ten relevant articles that evaluated the association of dietary vitamin B2 and breast cancer risk were available for the present meta-analysis. The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1 [23–32].

The ten articles on dietary vitamin B2 and breast cancer risk (12,268 cases, age range 20–80 years) were published between 1996 and 2015. Of ten studies, five were case–control studies [23–25, 27, 31] and five were cohort studies [26, 28–30, 32]. Three studies were performed in the United States [25, 28, 31], three in Europe [23, 24, 32], two in Asian [27, 29], and one each in Canada [26] and Australia [30]. Risk estimates in most studies were adjusted for age, BMI, parity, and alcohol consumption. Based on the NOS, the quality star was ranged from 6 to 9, implying a reasonable good quality of included studies (Table 2).

Highest vs. lowest vitamin B2 intake

Figure 2 shows the study-specific RRs of breast cancer risk and the summary RR pooled for the highest vs. lowest vitamin B2 intake. The summary RR of the highest (2.5 mg/days, mean) vs. lowest vitamin B2 intake (1.09 mg/days, mean) was 0.85 (95% CI = 0.76–0.95) for developing breast cancer. Little evidence of heterogeneity among the studies was observed (P = 0.086, I 2 = 40.7%) (Fig. 2).

Risk estimates of breast cancer associated with dietary vitamin B2 intake. Squares indicate study-specific risk estimates (size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight, i.e., the inverse of the variance); horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals (CIs); and diamonds indicate summary risk estimate with its corresponding 95% confidence interval

The sensitivity analysis indicated that the exclusion of any one study did not significantly influence the summary estimate of dietary vitamin B2 intake and risk of breast cancer, which implying that the results of the meta-analysis were reliable and stable. In addition, no evidence of publication bias was found (Egger’s P = 0.218).

In the subgroup analyses, we did not find any significant variations in summary RRs by study type, data collection, and adjusted by family history of breast cancer. However, stratified analysis by geographic region showed a stronger association in studies conducted in the Europe compared to those performed in US and other countries (Table 3).

Furthermore, five studies [27, 29–32] were reported RR estimates of the relationship between vitamin B2 intake and breast cancer risk according to ER status (Table 3). After stratifying the data in two subgroups (ER+ vs. ER−), no significant association of vitamin B2 with ER+ and ER− breast cancer risk was found (Table 3).

Dose–response meta-analysis

Ten studies were all available in the dose–response meta-analysis for the risk of breast cancer. The RR for each study and pooled RR for an increase of 1 mg/day are presented in Fig. 3. Overall, we found that an increment of 1 mg/day was significantly inversely related to breast cancer risk (RR = 0.94; 95% CI = 0.90–0.99). However, statistically significant heterogeneity across the studies was found (P < 0.001; I 2 = 74.8%).

Risk estimates of breast cancer associated with dietary vitamin B2 intake (1 mg/day increment). Squares indicate study-specific risk estimates (size of the square reflects the study-specific statistical weight, i.e., the inverse of the variance); horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals (CIs); and diamonds indicate summary risk estimate with its corresponding 95% confidence interval

Discussion

This is the first meta-analysis to evaluate the association of dietary vitamin B2 intake with the risk of breast cancer. The results showed that dietary vitamin B2 intake could weakly reduce the risk of breast cancer. In addition, no significant heterogeneity was found across the included studies.

In the stratified analysis by ER status, we did not find any significant association of vitamin B2 with ER+ and ER− breast cancer risk based on data adapted from five studies. However, we still cannot draw the firm conclusion based on the limited published information. In studies included in our analysis, some results were based on the small number of cases. Thus, more studies are still needed to further clarify this issue.

Vitamin B2 is cofactor in the one-carbon metabolism and might modulate the bioavailability of methyl groups and thus play an essential role in DNA stability and integrity. Disruption of one-carbon metabolism can interfere with DNA synthesis, repair, and methylation, which could promote cancer development. Furthermore, Vitamin B2 might also protect against breast cancer by mechanisms other than one-carbon metabolism, because it is also essential cofactors in numerous reactions central to human metabolism [33, 34].

This present meta-analysis exhibited several strengths. First, it is the first meta-analysis assessing the association of dietary vitamin B2 intake with the risk of breast cancer and we noticed that dietary vitamin B2 intake was inversely associated with breast cancer risk. Second, all the included studies had a high quality of assessment and the results from each original study were adjusted for a wide range of potential confounders. Third, the result of case–control studies and cohort studies is consistent. Furthermore, we also conducted a dose–response analysis to normalize the variability among studies in categorizing vitamin B2 intake. In addition, the results of dose–response analysis also showed an inverse association.

Nevertheless, there are also several potential limitations in this meta-analysis. First, as a meta-analysis of observational studies, it is not able to solve problems with confounding factors. Although most included studies adjusted for some established risk factors for breast cancer, other residual or unknown confounding cannot be ruled out as a potential explanation for the observed findings. Second, most studies only performed one single dietary assessment and any changes in dietary habits after that assessment will have been missed. Third, case–control studies have intrinsic limitation, including selective bias and recall bias. However, cohort studies are less susceptible to those biases, because data of dietary habits were assessed before diagnosis of breast cancer. In our present meta-analysis, the inverse association of vitamin B2 with breast cancer risk is also proved by cohort studies. Fourth, potential sources of between-study heterogeneity should be explored because of methodological differences among included studies. We applied appropriate inclusion criteria and conducted subgroup and sensitivity analysis, and we did not find significant heterogeneity among the studies. Finally, publication bias is a potential concern in any meta-analysis, because small studies with null results do not get published. In this meta-analysis, we did not search for unpublished studies or for original data. However, no evidence of substantial publication bias was found in this meta-analysis.

In summary, this present meta-analysis of observational studies indicates that dietary vitamin B2 intake could slightly decrease breast cancer risk.

References

Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65(2):87–108

Hulka BS, Moorman PG (2008) Breast cancer: hormones and other risk factors. Maturitas 61(1–2):203–213

Narod SA (2011) Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of breast cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 8(11):669–676

Xue F, Michels KB (2007) Intrauterine factors and risk of breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidence. Lancet Oncol 8(12):1088–1100

Tirona MT, Sehgal R, Ballester O (2010) Prevention of breast cancer (part I): epidemiology, risk factors, and risk assessment tools. Cancer Investig 28(7):743–750

Stevens VL, McCullough ML, Pavluck AL, Talbot JT, Feigelson HS et al (2007) Association of polymorphisms in one-carbon metabolism genes and postmenopausal breast cancer incidence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 16(6):1140–1147

Kim YI (2004) Folate and DNA methylation: a mechanistic link between folate deficiency and colorectal cancer? Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 13(4):511–519

Zhang YF, Shi WW, Gao HF, Zhou L, Hou AJ, Zhou YH (2014) Folate intake and the risk of breast cancer: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS One 9(6):e100044

Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Wolk A (2007) Folate and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 99(1):64–76

Liu Y, Yu QY, Zhu ZL, Tang PY, Li K (2015) Vitamin B2 intake and the risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(3):909–913

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 51(4):264–269 (W264)

Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M et al (2012) The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed 26 Mar 2016

DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7(3):177–188

Greenland S, Longnecker MP (1992) Methods for trend estimation from summarized dose-response data, with applications to meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 135(11):1301–1309

Orsini N, Bellocco R, Greenland S (2006) Generalized least squares for trend estimation of summarized doseresponse data. Stata J 6:40–57

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 21(11):1539–1558

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 315(7109):629–634

Cho E, Holmes M, Hankinson SE, Willett WC (2007) Nutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 16(12):2787–2790

Xu X, Gammon MD, Wetmur JG, Bradshaw PT, Teitelbaum SL, Neugut AI et al (2008) B-vitamin intake, one-carbon metabolism, and survival in a population-based study of women with breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 17(8):2109–2116

Dorjgochoo T, Shrubsole MJ, Shu XO, Lu W, Ruan Z, Zheng Y et al (2008) Vitamin supplement use and risk for breast cancer: the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 111(2):269–278

Stevens VL, McCullough ML, Sun J, Gapstur SM (2010) Folate and other one-carbon metabolism—related nutrients and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 91(6):1708–1715

Maruti SS, Ulrich CM, Jupe ER, White E (2009) MTHFR C677T and postmenopausal breast cancer risk by intakes of one-carbon metabolism nutrients: a nested case-control study. Breast Cancer Res 11(6):R91

Negri E, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S, D’Avanzo B, Talamini R, Parpinel M et al (1996) Intake of selected micronutrients and the risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer 65(2):140–144

Levi F, Pasche C, Lucchini F, La Vecchia C (2001) Dietary intake of selected micronutrients and breast-cancer risk. Int J Cancer 91(2):260–263

Chen J, Gammon MD, Chan W, Palomeque C, Wetmur JG, Kabat GC et al (2005) One-carbon metabolism, MTHFR polymorphisms, and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Res 65(4):1606–1614

Kabat GC, Miller AB, Jain M, Rohan TE (2008) Dietary intake of selected B vitamins in relation to risk of major cancers in women. Br J Cancer 99(5):816–821

Ma E, Iwasaki M, Kobayashi M, Kasuga Y, Yokoyama S, Onuma H et al (2009) Dietary intake of folate, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, genetic polymorphism of related enzymes, and risk of breast cancer: a case–control study in japan. Nutr Cancer 61(4):447–456

Maruti SS, Ulrich CM, White E (2009) Folate and one-carbon metabolism nutrients from supplements and diet in relation to breast cancer risk. Am J Clin Nutr 89(2):624–633

Shrubsole MJ, Shu XO, Li HL, Cai H, Yang G, Gao YT et al (2011) Dietary B vitamin and methionine intakes and breast cancer risk among Chinese women. Am J Epidemiol 173(10):1171–1182

Bassett JK, Baglietto L, Hodge AM, Severi G, Hopper JL, English DR et al (2013) Dietary intake of B vitamins and methionine and breast cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 24(8):1555–1563

Yang D, Baumgartner RN, Slattery ML, Wang C, Giuliano AR, Murtaugh MA et al (2013) Dietary intake of folate, B-vitamins and methionine and breast cancer risk among hispanic and non-hispanic white women. PLoS One 8(2):e54495

Cancarini I, Krogh V, Agnoli C, Grioni S, Matullo G, Pala V et al (2015) Micronutrients involved in one-carbon metabolism and risk of breast cancer subtypes. PLoS One 10(9):e0138318

Rivlin RS (1970) Riboflavin metabolism. N Engl J Med 283:463–472

Powers HJ (2003) Riboflavin (vitamin B-2) and health. Am J Clin Nutr 77(6):1352–1360

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author Lanting Yu declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author Yuyan Tan Lin Zhu declares that he/she has no conflict of interest. Author Lin Zhu declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, L., Tan, Y. & Zhu, L. Dietary vitamin B2 intake and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 295, 721–729 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4278-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-016-4278-4