Abstract

Purpose

To achieve a better understanding of issues related to sexual function and quality of life (QOL) of women with cervical cancer before radiotherapy treatment.

Methods

A pilot study with 80 women with cervical cancer from Jan/2013 to Mar/2014. The outcome variables were sexual function assessed using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and QOL, assessed using the World Health Organization questionnaire. Independent variables were clinical and sociodemographic data. Statistical analysis was carried out using Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney test, ANOVA and multiple linear regression.

Results

The mean age was 48.1 years, 57.5 % were premenopausal and 55 % had clinical stage IIIB. Thirty percent had been sexually active in the 3 months prior to their interviews. The main adverse events during sexual intercourse were bleeding (41.7 %), lack of pleasure (33.3 %), dyspareunia (25 %), and vaginal dryness (16.7 %). The 18 women who had been sexually active in the previous month showed significant sexual dysfunction (total mean FSFI score = 25.6). Advanced clinical stage, using any chronic medication and not having undergone surgery for cancer were negatively correlated with QOL. Higher family income, a longer duration of schooling and no smoking were positive correlated with QOL.

Conclusions

One-third of women with cervical cancer were sexually active 3 months prior to their interviews, but have concomitant significant sexual dysfunction. Factors related to the disease are primarily responsible for the deterioration of sexual function. QOL is influenced not only by factors related to the cancer itself, but also by lifestyle habits, comorbidities, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cervical cancer remains the third most frequent cancer among Brazilian women, with an estimated 15,590 new cases in 2014 [1]. The mortality rate in the two largest cities of the country dropped significantly between 1980 and 2009 and a lower relative risk of death from cervical cancer after the year of 2000 has been documented in these cities, especially for women born after 1960 [2]. However, evaluation of data from throughout Brazil has shown that survival rates at 5 years have been stable over the last two decades, being 60.2 % between 1995 and 1999, 67.5 % between 2000 and 2004, and 61.1 % between 2005 and 2009 [3].

Pelvic radiotherapy is one of the main therapeutic modalities for locally advanced cervical cancer [4]. This usually comprises a combination of teletherapy (external beam radiation therapy) and brachytherapy administered for up to 8 weeks. Concomitant chemotherapy improves overall survival rate and disease-free interval and reduces local recurrence and distant metastases in selected patients [5–7]. When there is no need to preserve fertility, pelvic radiation therapy may be indicated even for women with early-stage tumors (from clinical stage IA1) if there is tumor invasion of the lymphovascular space [8].

With the introduction of increasingly widespread social programs for preventing cervical cancer and more effective therapeutic techniques, it is expected that the mortality of the disease will continue to fall [2]. Thus, not only the physical effects of the disease and its treatment, but also the psychological and sexual effects, that are components of QOL, have become increasingly important [9, 10]. Some studies report that radiotherapy is the treatment modality most associated with worsening of quality of life and sexual function in survivors of cervical cancer [9, 11–13] and another in particular has analyzed adverse effects associated with treatment [14–16]. Few studies, however, have described quality of life at start of therapy [17, 18] and even fewer have reported these women´s sexual function [19, 20]. To achieve a better understanding of issues related to sexual function and quality of life of women with cervical cancer at initiation of radiotherapy, a pilot study was conducted on women referred for radiotherapy to the Women’s Hospital of the State University of Campinas, Brazil.

Methods

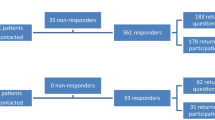

A pilot study was conducted at the Women’s Hospital of the State University of Campinas (Unicamp) from January 2013 to March 2014. The sample consisted of women with cervical cancer, aged 18–75 years, who had been invited to participate in a clinical trial on the effects of various treatments for vaginal stenosis after radiotherapy. Women who had already undergone pelvic radiotherapy treatment for cervical cancer, had used hormone therapy in the past 6 months, had any contraindication to the use of topical estrogen or had an intestinal disease such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease were excluded. During the first consultation before the start of radiotherapy treatment, interviews of average length 40 min were conducted by the main investigator in an appropriate room in the hospital’s radiotherapy division. Data were acquired by using a questionnaire consisting of two sections: in the first section the women were asked questions concerning clinical and sociodemographic data; whereas in the second section, data were extracted from their medical records concerning the characteristics of their tumors. Questionnaires were also used to evaluate sexual function (Female Sexual Function Index) [21] and to assess quality of life (WHOQOL-bref) [22]. Ninety-four women were invited to participate; 14 refused, mainly because of lack of time to complete the survey. Thus, the final sample comprised 80 women, all of whom signed free and informed written consents before the interviews. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of UNICAMP (Number 8933).

Dependent variables

Sexual function

The “Female Sexual Function Index” [19] was used for sexual evaluation. This questionnaire had already been validated in Portuguese [23] and consists of nineteen questions grouped into six domains; namely desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain. All questions are multiple choice and each answer is assigned a value of zero to six. A zero score in a domain indicates that the woman reported no sexual activity in the previous month. A total score of less than or equal to 26.55 indicates the presence of sexual dysfunction. To obtain unambiguous total scores, the questionnaire was administered only to women who reported sexual activity in the previous month. The domain and total scores were analyzed as continuous variables [21, 23].

Quality of life

The abbreviated version of the World Health Organization questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) was used to assess quality of life. WHOQOL-bref is a generic instrument for assessing quality of life that has previously been translated and validated in Portuguese [22]. It consists of 24 questions divided into four domains: physical, psychological, social relationships, and environment plus two additional questions that assess general quality of life and health. This instrument does not allow use of a total score. Higher scores in the various domains correspond to better quality of life in that domain. Scores for the various domains were analyzed as continuous variables.

Independent variables

The independent variables assessed were: age (in years), race, clinical stage (IB1/IB2/IIB/IIIB), menopausal status (premenopausal/postmenopausal), marital status (single, married, living together, widowed, and divorced), schooling (≤8/>8 years), body mass index (≤27.8/>27.8), smoker (yes/no), depression (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), multimorbidity—two or more chronic illnesses (yes/no), family income (≤US$750/>US$750), surgery (yes/no), employment (yes/no), sexual partner (yes/no), sexually active in the last 3 months (yes/no), number of episodes of sexual intercourse per week (0/1/>1), symptoms during sexual intercourse in the last 3 months (none/vaginal bleeding/lack of pleasure/dyspareunia/vaginal dryness), and reason for not having sexual intercourse (no partner/vaginal bleeding/pain/surgery/vaginal discharge/sexual partner with health problems).

Statistical analysis

Initially, a descriptive analysis of data using frequency distributions was performed. Variables were expressed as mean, median, standard deviation, maximum, and minimum values. Next, bivariate analyses were performed to assess associations between dependent and independent variables. The tests used for bivariate analysis were Student’s t test, the Mann–Whitney test, ANOVA and ANOVA by Kruskal–Wallis depending on the normality distribution of data and the number of categories of independent variables. Finally, for the dependent variable of quality of life, multiple linear regression models were built for each domain of the WHOQOL-BREF [24]. The program used for the analysis was SAS, version 9.2 [25].

Results

A total of 80 women with cervical cancer participated in the interviews. Their mean age was 48.1 ± 13.5 years (median 48.0; range 20.6–75.6), 56.3 % (n = 45) of participants reported having studied 8 years or fewer, 57.5 % (n = 46) of women were premenopausal, and 51.3 % (n = 41) reported family incomes below US$750. Forty-four women (55 %) had clinical stage IIIB cervical cancer. Some relevant clinical and sociodemographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Forty-nine women (62 %) reported having sexual partners and 30 % (n = 24) had been sexually active in the 3 months prior to their interviews. Of these 41.7 % (n = 10) reported having more than one episode of sexual intercourse per week. The main adverse events that had occurred during sexual intercourse were bleeding (41.7 %; n = 10), lack of pleasure (33.3 %; n = 8), dyspareunia (25 %; n = 6), and vaginal dryness (16.7 %; n = 4). Among women who had sexual partners, the main reason for not being sexually active was vaginal bleeding during intercourse (32.1 %; n = 18). Some of the clinical symptoms and aspects of sexual function are shown in Table 2.

FSFI and WHOQOL-BREF scores are shown in detail in Table 3. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire was administered only to women who had been sexually active in the previous month to avoid ambiguity in data analysis [21]. Women with cervical cancer who had been sexually active in the previous month showed significant sexual dysfunction (total mean FSFI score = 25.6). Analysis of the factors associated with worsening of sexual function revealed that having undergone surgery before radiotherapy was negatively associated with arousal (p = 0.01) and satisfaction (p = 0.02) domains, both associations being statistically significant. Women with vaginal bleeding during intercourse had significantly lower scores in the orgasm (p = 0.04) and satisfaction (p = 0.03) domains than those who did not. Women with any adverse symptoms during intercourse had lower scores in the pain domain than those who did not (p = 0.02). Lack of pleasure during intercourse was negatively associated with the orgasm domain (p = 0.04) whereas smoking was positively associated with total FSFI score (p = 0.04). No factor was associated with the desire and lubricating domains (Table 4).

For the dependent variable of quality of life, multiple linear regression models were built for each WHOQOL-bref domain. In the physical domain, advanced clinical stage correlated negatively with quality of life (β = −2.19; p = 0.04) whereas higher family income was positively correlated (β = 0.0041, p = 0.03). As for the psychological domain, using any medication was negatively related to quality of life (β = −9.54; p = 0.02). In the environment domain, having a higher family income was positively related (β = 0.0044, p < 0.01), whereas having an advanced clinical stage was negatively related to quality of life (β = −1.31, p = 0.03). Non-smokers (β = 22.02; p < 0.01) and those with longer duration of schooling (β = 3.40, p = 0.03) had a positive association with overall quality of life. Not having undergone surgery for cancer (β = −16.03; p = 0.01) and having longer duration of schooling (β = −4.86, p < 0.01) were inversely associated with general health, whereas being a non-smoker was positively associated with general health (β = 16.35; p = 0.01). No factors were associated with the social relationships domain of the questionnaire (Fig. 1).

Discussion

The aim of this pilot study was to gain information about aspects of sexuality and quality of life of women with cervical cancer at the beginning of treatment. Many studies have reported issues related to sexuality and quality of life of long time survivors of cervical cancer; however, there are few published studies on the sexual function of women who have recently begun treatment and the factors that influence their quality of life [17–19].

Thirty percent of the women reported having had regular sex in the 3 months prior to their interviews. Of these, approximately 40 % engaged in more than one episode of sexual intercourse per week. This frequency is higher than that previously reported. In 2011, Vaz et al. reported that 21.5 % of women referred for radiotherapy for endometrial or cervical cancer were sexually active. It is noteworthy, however, that the mean age of these women was higher, most were postmenopausal, and a larger proportion of them had no sexual partner than in our cohort [26]. In 2014, Kirchheiner et al. reported that only 12 % of women with locally advanced cervical cancer had been sexually active before the start of radiotherapy; however, the mean age was also higher than in our cohort [27].

Sexual function may be impaired by symptoms such as vaginal bleeding [26, 28]. In this study, vaginal bleeding during intercourse was both the main reported adverse effect and the main reason for women not continuing to be sexually active. This association was expected: it occurred with women with locally advanced, large tumors, and thus a high risk of bleeding. Symptoms such as lack of pleasure during sexual intercourse, dyspareunia, and vaginal dryness were also common, and probably had similar origins. Women with a serious disease like cervical cancer face high levels of stress and concerns about health; these factors may inhibit their sexuality. Additionally, they may feel guilty in relation to sexual activity, because the virus that causes cervical neoplasia is transmitted by the venereal route. A combination of such factors may lead to a lower degree of desire and arousal, causing decrease in lubrication with consequent vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and lack of pleasure. Women with gynecological cancer may experience decreased sexual desire from the moment of the diagnosis of malignancy [29]. Another possible inhibitor of sexuality is that approximately one-third of women with cervical cancer believe that sexual relations can exacerbate disease [30].

The FSFI questionnaire was administered to women who had engaged in sexual activity in the 30 days prior to the interview. Although they had been sexually active in the previous month, these women had significant impairment of sexual functioning. Previous studies reported that sexual function in gynecologic [26, 28] and cervical cancer [31] may be impaired by cancer diagnosis, cancer-related symptoms and surgery. The lowest scores were recorded in the desire and arousal domains, which are consistent with the reported symptoms of dyspareunia, lack of pleasure, and vaginal dryness. Analysis of the factors associated with worsening of sexual function in the assessed domains revealed a significant association between having undergone surgery before the start of radiotherapy and low scores in the arousal and satisfaction domains. Sexual arousal dysfunction was observed in women with cervical cancer before and after surgery when compared with healthy controls [31]. Most women whose initial form of treatment had been surgery had undergone radical hysterectomy plus pelvic lymphadenectomy (Wertheim–Meigs), a procedure with high morbidity that requires a long period of postoperative convalescence. This added to the stress of a cancer diagnosis may have contributed to lower levels of arousal and less satisfaction with sexual activity. Women with bleeding during intercourse were also less satisfied and experienced greater difficulty in achieving orgasm. In addition, the orgasm domain was compromised in women who reported lack of pleasure. In the pain domain, the only associated factor was having any adverse symptom (s) during intercourse. Thus, we found that sexual function in women with cervical cancer does not depend on sociodemographic characteristics, lifestyle habits, or comorbidities. Rather, postoperative convalescence and adverse symptoms related to the tumor are the main factors responsible for decreased sexual function. We believe that the positive association between smoking and higher total score on the questionnaire is attributable to the small number of women who had been sexually active in the previous month and possible interference by other unidentified confounding variables.

WHOQOL-bref is a generic instrument that assesses four domains related to quality of life and has two questions about overall quality of life and general health [22]. More than half the women in this study had clinical stage IIIB cervical cancer and had worse scores in the physical and environmental domains of the questionnaire than women with earlier stages. In 2008, Distefano et al. found that women with locally advanced cervical cancer had worse quality of life scores in the physical domain than did women with earlier stages of cervical cancer [32]. Other recent studies have also shown that advanced cervical cancer affects the quality of life in various domains [33, 34]. We found no association between multimorbidity (two or more chronic illnesses) and quality of life; however, users of chronic medications such as antihypertensive and oral antidiabetic drugs had worse scores in the psychological domain than those not taking such medications. It is probable that adding another health problem to subjects who already have health issues precipitates feelings of hopelessness, further affecting quality of life. Being a non-smoker had a beneficial effect on overall quality of life and general health. Frumovitz et al. reported an association between smoking and impaired emotional and mental well-being in women with cervical cancer. They postulated that smokers who are aware that smoking tobacco is associated with cancer have a more negative perception of their health status [11]. Women who had not undergone surgery prior to the start of radiation therapy had worse scores on the question regarding general health. A previous study using the same questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) reported a positive relationship between undergoing surgery and general health scores [18]. These women may have believed that surgery offers a greater possibility of curing cancer, leading to a positive effect on quality of life.

Some sociodemographic characteristics were independently associated with quality of life of women with cervical cancer. It is noteworthy that this study was conducted in a public health service; most women attending such services have financial problems. Problems such as delay in diagnosis and treatment may have contributed to deterioration in quality of life. Have a higher family income was positively associated with the physical and environmental domains of the questionnaire. Indeed, a previous study showed that women with locally advanced cervical cancer who were unemployed had the lowest scores for quality of life in all domains investigated [32]. More recently, a study of US-American survivors of cervical cancer showed a strong independent association between low family income and poorer quality of life [35]. The association between schooling and quality of life was ambiguous in this study. Have attended school for longer was positively associated with overall quality of life; that is, women with higher education had better scores. However, the association between schooling and general health was the opposite; women with more education had lower scores for general health. An association between attending school for longer and better quality of life in women with locally advanced cervical cancer has been well documented [32, 36]; the inverse association found in this study needs to be further researched.

This study has some limitations. The cross-sectional design, make it impossible to draw conclusions about cause and effect. Because this was a pilot study that was a component of an ongoing clinical trial, the sample comprised the women who were eligible for the clinical trial. We did not use a questionnaire that specifically assesses quality of life in women with cancer. To our knowledge, there is no such questionnaire validated for the Portuguese language spoken in Brazil. However, the generic questionnaire that we did use (WHOQOL-BREF) is able to identify various aspects of quality of life in women with cervical cancer. There were too few women who had been sexually active in the 30 days prior to the interview to allow multivariate analysis of the dependent variable “sexual function”. It is recommended that FSFI questionnaire be administered only to women who have been sexually active in the previous month in order to avoid ambiguity in data analysis [21].

A significant proportion of women with cervical cancer in early treatment are frequently sexually active but have concomitant significant sexual dysfunction. Factors related to the disease and its treatment, such as adverse events and postoperative convalescence, are primarily responsible for the deterioration of sexuality. On the other hand, quality of life is influenced not only by factors related to the cancer itself, but also by lifestyle habits, comorbidities and sociodemographic characteristics such as low family income and education. This information is useful for identifying women who need more support and attention during the course of therapy for cervical cancer.

References

Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (2014). Estimativa 2014. Incidência de Câncer no Brasil. http://www.inca.gov.br/estimativa/2014/. Accessed 23 Jan 2015

Meira KC, Silva GA, Silva CM et al (2013) Age-period-cohort effect on mortality from cervical cancer. Rev Saude Publica 47(2):274–282

Allemani C, Weir HK, Carreira H et al (2015) Global surveillance of cancer survival 1995-2009: analysis of individual data for 25 676 887 patients from 279 population-based registries in 67 countries (CONCORD-2). Lancet 385(9972):977–1010

Banerjee R, Kamrava M (2014) Brachytherapy in the treatment of cervical cancer: a review. Int J Womens Health 6:555–564

Green JA, Kirwan JM, Tierney JF et al (2001) Survival and recurrence after concomitant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer of the uterine cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 358(9284):781–786

Green JA, Kirwan JJ, Tierney J et al (2010). Concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer of the uterine cervix. Cochrane Data base of systematic reviews. In: The Cochrane library, issue 1 Art. n°. CD002225. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002225.pub4

Khalil J, El Kacemi H, Afif M, Kebdani T, Benjaafar N (2015) Five years’ experience treating locally advanced cervical cancer with concurrent chemoradiotherapy: results from a single institution. Arch Gynecol Obstet. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3712-3

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2014) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines)—Cervical Cancer. Version 2.2015. http://www.nccn.org. Accessed 15 Dec 2014

Ye S, Yang J, Cao D, Lang J, Shen K (2014) A systematic review of quality of life and sexual function of patients with cervical cancer after treatment. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24(7):1146–1157

Iavazzo C, Johnson K, Savage H, Gallagher S, Datta M, Winter-Roach BA (2015) Sexuality issues in gynaecological oncology patients: post treatment symptoms and therapeutic options. Arch Gynecol Obstet 291(3):653–656

Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR et al (2005) Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 23:7428–7436

Park SY, Bae D, Nam JH et al (2007) Quality of life and sexual problems in disease-free survivors of cervical cancer compared with the general population. Cancer 110(12):2716–2725

Greimel ER, Winter R, Kapp KS et al (2009) Quality of life and sexual functioning after cervical cancer treatment: a long-term follow-up study. Psychooncology 18(5):476–482

Brand AH, Bull CA, Cakir B (2006) Vaginal stenosis in patients treated with radiotherapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer 16:288–293

Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Tharanov I, Petersen MA, Machin D (2003) Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys 56(4):937–949

Vaz AF, Conde DM, Costa-Paiva L, Morais SS, Esteves SB, Pinto-Neto AM (2011) Quality of life and adverse events after radiotherapy in gynecologic cancer survivors: a cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 284(6):1523–1531

Visser MR, van Lanschot JJ, van der Velden J et al (2006) Quality of life in newly diagnosed cancer patients waiting for surgery is seriously impaired. J Surg Oncol 93(7):571–577

Vaz AF, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM et al (2007) Quality of life of women with gynecologic cancer: associated factors. Arch Gynecol Obstet 276(6):583–589

Yeo BK, Perera I (1995) Sexuality of women with carcinoma of the cervix. Ann Acad Med Singapore 24(5):6768

Incrocci L, Jensen PT (2013) Pelvic radiotherapy and sexual function in men and women. J Sex Med 10(1):53–64

Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J et al (2000) The Female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 26:191–208

Fleck MP, Louzada S, Xavier M et al (2000) Application of the Portuguese version of the abbreviated instrument of quality life WHOQOL-bref. Rev Saude Publica 34:178–183

Hentschel H, Alberton DL, Goldim JR et al (2007) Validação do female sexual function index (FSFI) para uso em língua portuguesa. Rev HCPA 27(1):10–14

Altman DG (1999) Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton

SAS Institute Inc. (1999–2001) SAS/STAT software changes and enhancements though release 8.2 Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc. 1999–2001

Vaz AF, Pinto-Neto AM, Conde DM, Costa-Paiva L, Morais SS, Pedro AO, Esteves SB (2011) Quality of life, menopause and sexual symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors: a cohort study. Menopause 18:662–669

Kirchheiner K, Nout RA, Czajka-Pepl A et al (2015) Health related quality of life and patient reported symptoms before and during definitive radio (chemo)therapy using image-guided adaptive brachytherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer and early recovery—a mono-institutional prospective study. Gynecol Oncol 136(3):415–423

Stead ML (2007) Psychosexual function and impact of gynaecological cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 21(2):309–320

Thranov I, Klee M (1994) Sexuality among gynecologic cancer patients—a cross-sectional study. Gynecol Oncol 52(1):14–19

Flay LD, Matthews JH (1995) The effects of radiotherapy and surgery on the sexual function of women treated for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31:399–404

Aerts L, Enzlin P, Verhaeghe J, Poppe W, Vergot I, Amant F (2014) Long-term sexual functioning in women after surgical treatment of cervical cancer stages IA to IB: a prospective controlled study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24(8):1527–1534

Distefano M, Riccardi S, Capelli G et al (2008) Quality of life and psychological distress in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered pre-operative chemoradiotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 111:144–150

Azmawati MN, Najibah E, Hatta MD et al (2014) Quality of life by stage of cervical cancer among Malaysian patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 15(13):52836

Hung MC, Wu CL, Hsu YY et al (2014) Estimation of potential gain in quality of life from early detection of cervical cancer. Value Health 17(4):482–486

Greenwald HP, McCorkle R, Baumgartner K et al (2014) Quality of life and disparities among long-term cervical cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv 8(3):419–426

Osann K, Hsieh S, Nelson EL et al (2014) Factors associated with poor quality of life among cervical cancer survivors: implications for clinical care and clinical trials. Gynecol Oncol 135(2):266–272

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Regina Celia Grion, Luiz Francisco Baccaro, Ana Francisca Vaz, Lucia Costa-Paiva, Delio Marques Conde and Aarao Mendes Pinto-Neto declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding organization

Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) number 2012/09215-7.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grion, R.C., Baccaro, L.F., Vaz, A.F. et al. Sexual function and quality of life in women with cervical cancer before radiotherapy: a pilot study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 293, 879–886 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3874-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-015-3874-z