Abstract

Psoriasis is a prevalent skin disease that impairs multiple domains of quality of life (QoL). Pruritus, a common symptom in patients with psoriasis, may directly affect sleep, but studies investigating this are limited. We investigated the relationships between pruritus and sleep in 104 in-patients with psoriasis, who underwent dermatological assessment and completed questionnaires to determine psoriasis severity, pruritus intensity, sleep quality, QoL (skin disease-specific and generic), depressive mood and anxiety. In total, 80% of patients reported pruritus, and 39% had sleep disturbances, most commonly awakenings during sleep (33%) and sleepiness during the daytime (30%). Sleep impairment was more frequent in patients with pruritus, who had more difficulty falling asleep (P = 0.031). Overall, 14% of all patients and 34% of the patients who reported sleep disturbances reported that their sleep problems were caused by pruritus. Patients who reported sleep disturbances had lower generic QoL. Pruritus in patients with psoriasis was frequent and relevant, as evidenced by the higher rate of sleep problems in this patient group, and it was linked to a lower QoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a highly prevalent and chronic skin disease that impairs overall quality of life (QoL). Psoriasis exerts a negative impact on many specific aspects of patients’ daily functioning, including physical (limited mobility in patients with psoriatic arthritis [PsA] and daily activities), psychological (anxiety, depression and stigmatization) and social functioning (sports, sexual behaviour and work) [11, 12, 19]. Its influence on sleep has been reported [10], but this is not adequately understood. Many studies reporting sleep disturbances in psoriasis are aimed at investigating general QoL impairment, and information on sleep disturbances have been extracted from general QoL measurements [19, 22]. Sleep is an important aspect of overall health. Acquiring sufficient high-quality sleep is essential for our physical and emotional well-being, as evidenced by the ill effects on individuals who suffer from insomnia [29].

One particularly burdensome and clinically important symptom of psoriasis is pruritus [41]. In addition to several other symptoms faced by patients with psoriasis, pruritus alone can cause great embarrassment and discomfort [9, 28]. In the last 2 decades, a high prevalence of pruritus in patients with psoriasis has been revealed, with levels estimated to be as high as 64–89% [28, 30, 41]. Interestingly, pruritus intensity is not necessarily proportional to the severity of psoriasis [28, 41], and it is significantly associated with poor general QoL [2, 23]. Pruritus is known to negatively impact sleep in patients with other dermatological conditions including chronic urticaria, chronic pruritus (CP) and atopic dermatitis (AD) [18], and improvements in AD through treatment with nemolizumab resulted in better sleep [16, 36]. Pruritus severity in patients with psoriasis is lower than that in AD or CP [26, 31], but it often intensifies in the evening, thereby potentially interfering with sleep [33].

The aim of the study was to characterise pruritus and sleep disturbances in patients with psoriasis, to investigate the relationship between pruritus and sleep problems, to identify predictors for sleep impairment and to assess the impact of pruritus and sleep disturbances on patients’ QoL.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 104 consecutive in-patients (median age 46, range 18–74 years, all Caucasian) with psoriasis were recruited to participate in this study from the Department of Dermatology, Medical University of Łódź. Patients with comorbid, controlled psoriatic arthritis (PsA, i.e. with no need for a change in current therapy due to active symptoms of PsA) were included. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Medical University of Łódź.

Clinical assessment

During this study, patients were examined by a dermatologist who recorded medical history and assessed disease severity using the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI). Patients assessed the average severity of their pruritus in the last week using the 10-cm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the four-item Itch Questionnaire, which evaluates itch distribution, frequency, severity and sleep disturbances due to itch [37]. The maximum pruritus score for the four-item Itch Questionnaire is 19 points.

Sleep disturbances were assessed by questions about average sleep duration in hours, dichotomous (yes or no) questions about overall sleep disturbances, consumption of sleeping pills, difficulties falling asleep (sleep latency), awakenings during the night, awakenings in the morning with an inability to fall asleep again, and sleepiness during the daytime. Patients were also asked if their sleep disturbances were caused, in their opinion, by pruritus.

Psychometric assessment

Psychometric parameters were assessed using a range of validated self-reported questionnaires. Skin disease-specific QoL impairment was assessed using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) [6]. The DLQI scores range from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating lower QoL. Generic QoL impairment was assessed using the World Health Organization QoL-BREF (WHOQoL-BREF) [32]. This questionnaire enables assessment of the global QoL and its four specific domains: physical, psychological, social and environmental, each scored from one to five, with higher scores reflecting better QoL. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to assess depressive mood [3]. The score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was employed to evaluate two separate dimensions of anxiety, a current state of anxiety, and anxiety as a personal trait [34]. Scores of both domains range from 20 to 80, with higher scores reflecting greater anxiety.

Statistical analyses

Parametric variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-parametric variables as median (lower and upper quartiles). Differences in distribution of categorical variables were tested using the Chi squared test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Differences between two groups of independent, interval variables were tested using the unpaired t test, Welch’s unequal variances t test or Mann–Whitney U test, where appropriate. Linear relationships between two datasets of normally distributed continuous variables were tested using Pearson’s correlation, and if the data were non-parametric, Spearman’s correlation was used. Differences between three groups of independent, interval parametric variables were tested using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test, and for non-parametric variables, using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn–Bonferroni post-test. Multiple logistic regression was used to investigate the complex prediction models of sleep impairment by clinical (PASI, pruritus presence or intensity, duration of psoriasis, comorbidities, body mass index), demographic (age, gender, employment status) and psychological variables (depression and anxiety). The variable selection to the final regression model was supported by the forward selection method. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Pruritus is frequent in patients with psoriasis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all patients are presented in Table 1. In total, 79.8% (n = 83) of patients reported pruritus. Female patients reported pruritus significantly more often than male patients (91% vs. 71%, P = 0.012). Chronic plaque psoriasis was the most prevalent type being present in 93.3% (n = 97) of patients. The overall frequency of PsA was low at 19.2% (n = 20). No differences were detected in the demographic and clinical parameters, including PASI, between patients with and those without pruritus (Table 1).

In patients with psoriasis, the average pruritus severity is moderate and correlates with the severity of psoriasis, albeit weakly

In the 83 patients who reported pruritus, intensity on the VAS was 4.73 ± 2.26. Correlation between both measures of pruritus intensity (VAS and the 4-item Itch Questionnaire) was high (rho = 0.666, P < 0.001). Seven of 79 patients with pruritus (8.9%) reported having generalised pruritus (4 patients with pruritus did not respond).

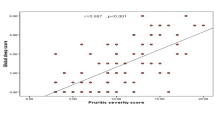

Psoriasis severity and extent (PASI) and pruritus were correlated, albeit weakly, with both the VAS and the 4-item Itch Questionnaire in patients who reported pruritus (rho = 0.356, P = 0.002 and rho = 0.237, P < 0.045, respectively) and for all patients (rho = 0.304, P = 0.002, and rho = 237, P = 0.022, respectively). In total, 21 patients (20.2%) reported having no pruritus.

Median PASI in patients with generalised pruritus (22.2, lower quartile 15.60, upper quartile 31.80, n = 7) was higher than in the patients without pruritus (10.40, lower quartile 3.40, upper quartile 23.10, n = 21; P = 0.037, post-test P = 0.031) and in those patients with localised pruritus (12.00, lower quartile 8.25, upper quartile 18.60, n = 65), a difference that was not statistically significant (post-test P = 0.091, Fig. 1).

Psoriasis severity (Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, PASI) in patients without pruritus, with localised pruritus and with generalised pruritus. Kruskal–Wallis, P = 0.037, PASI in patients with generalised itch vs. PASI in patients without pruritus, Dunn–Bonferroni post-test, P = 0.031, vs. PASI in patients with localised pruritus, Dunn–Bonferroni post-test, P = 0.091

Many patients report overall sleep problems, and sleep disruption is the most frequently reported type of sleep disturbance

Overall, 39.4% (n = 41) of patients reported sleep disturbances (Table 2). Awakening during sleep was the most common complaint (32.7%, n = 34), followed by sleepiness during the daytime (29.8%, n = 31) and difficulties falling asleep (27.9%, n = 29). Less frequently, patients complained about early morning awakenings (20.2%, n = 21) and the use of sleeping medication (15.4%, n = 16).

Difficulty falling asleep is significantly associated with pruritus in patients with psoriasis

Overall, 87.8% (n = 36) of patients who complained about general sleep impairment and 73.3% (n = 44) of patients who did not, had pruritus, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = 0.063, Table 2).

The sleep latency domain (difficulties in falling asleep) was significantly more frequently impaired in patients with pruritus (93.1% of patients who reported difficulties in falling asleep and 73.9% of patients who did not, had pruritus, P = 0.031, Table 2).

Fourteen patients (13.5% of all patients and 34.1% of the 41 patients who reported sleep disturbances) reported that their sleep problems were caused by pruritus (Fig. 2). In these patients, pruritus intensity on the VAS was higher (median, lower, and upper quartiles: 5.2, 4.0, 8.0, respectively) than in the remaining patients with sleep disturbances (median, lower, and upper quartiles: 3.0, 1.0, 5.0, respectively; P = 0.011, post-test P = 0.011) and in patients without sleep problems (median, lower, and upper quartiles: 3.0, 0.0, 6.5, respectively; post-test P = 0.023, Fig. 2).

Itch intensity (Visual Analogue Scale, VAS) in patients who did not report sleep disturbances, who reported sleep disturbances due to pruritus and in the remaining patients with sleep disturbances. The dotted, horizontal line denotes upper range limit of the scale. Kruskal–Wallis, P = 0.011, pruritus (VAS) in patients who reported sleep problems due to pruritus, vs. remaining patients with sleep disturbances, Dunn–Bonferroni post-test, P = 0.011 and vs. patients without sleep problems, Dunn–Bonferroni post-test, P = 0.023, pruritus (VAS) in patients without sleep problems vs. patients with sleep problems not due to pruritus, Dunn–Bonferroni post-test, P = 1.000

Pruritus intensity measured using the 4-item Itch Questionnaire was higher in patients who reported that their sleep problems were caused by pruritus (median, lower, and upper quartiles: 11.0, 8.0, 14.0, respectively) than in the remaining patients with sleep disturbances (median, lower, and upper quartiles: 4.5, 3.0, 7.0, respectively; P = 0.001, post-test P = 0.002) and without sleep disturbances (median, lower, and upper quartiles: 5.0, 0.0, 6.0, post-test P < 0.001).

Trait anxiety, higher age, comorbid depression and psoriatic arthritis predict sleep disturbances

We investigated the complex prediction models of different sleep domains by demographic, clinical and psychological variables using multiple logistic regression. The obtained model explained 30% of the variance in overall sleep disturbance (Nagelkerke R-squared = 0.295, Table 3). Higher trait anxiety predicted sleep impairment in most domains, except in the use of sleeping medication (Table 3). Further factors that predicted impairment of different domains of sleep were higher age and comorbid depression (but not the current depressive mood, as measured using BDI). Comorbid PsA, higher age and trait anxiety predicted awakenings during sleep (Table 3).

Sleep disturbances and pruritus negatively impact generic quality of life

Patients without pruritus presented with better skin disease-specific QoL (DLQI) vs. patients with mild and moderate to severe pruritus (Supplementary Table 1s). Patients without pruritus also presented with better generic QoL (WHOQoL-BREF) in all domains, except the psychological and social domains, than patients with moderate to severe pruritus. There was no difference in depressive mood and anxiety between patients with and without pruritus (Supplementary Table 1s). Patients who reported sleep disturbances had lower generic QoL in all domains, but their skin disease-specific QoL did not differ from that in the patients without sleep disturbances (Supplementary Table 2s).

Discussion

Our study indicates that pruritus in patients with psoriasis is frequent and relevant, its average intensity is moderate, it can directly affect sleep, and it can result in a lower QoL. In our patient population, the prevalence of pruritus was almost 80% and its intensity was weakly associated with the severity of psoriasis, as has been previously reported [41]. A higher proportion of psoriasis patients with pruritus complained of sleep impairment. Difficulty falling asleep at night was associated with pruritus, which makes sense as pruritus in patients with psoriasis tends to appear mainly in the evenings and at night [41]. Thus, a symptom that causes so much irritation and discomfort could readily interfere with the ability to fall asleep. High prevalence and intensity of nocturnal pruritus, frequently interfering with sleep was reported in patients with chronic pruritus of different origin, including psoriasis.[13, 20, 42]. Pruritus intensity did not appear to be sufficiently strong to result in awakenings during the night in our patient group, however, this could differ in patients with more severe pruritus. Lavery et al. demonstrated that in patients with chronic pruritus of different origin and intensity, severity of nocturnal pruritus correlated with severity of sleep disturbances [20]. In a recent study, patients with psoriasis, who presented with more intense pruritus than our patients suffered from sleep latency, impaired sleep duration, efficiency, disturbances, use of sleeping medications and the total sleep quality [15]. Jensen et al. reported that pruritus severity in psoriasis was the main predictor of sleep impairment, including sleep latency, duration and efficiency [14].

Over one-third of patients with sleep disturbances reported that, in their opinion, their sleep problems were caused by pruritus. Amongst this group, higher pruritus intensity was recorded, indicating a direct link between sleep problems and level of severity. Of note, patients who reported that their sleep problems were due to pruritus, exclusively comprised of those with a VAS score of three or above. This supports the use of the previously proposed range of 0–3 for mild and ≥ 3 for moderate to severe pruritus on the VAS and its relevance in the context of sleep problems [17, 27]. Thus, a therapeutic goal in patients with sleep complaints due to pruritus could be to reduce pruritus intensity to three or below on the VAS. This observation must be confirmed in a larger population in patients with other pruritic conditions and in clinical studies.

The importance of good sleep for overall well-being and daily functioning is well documented, with a lack of sleep negatively affecting many aspects of life [29], this point is reinforced in our study whereby QoL (WHOQoL-BREF) was significantly lower for every domain in patients with sleep disturbances vs. patients without. Insomnia and disturbances in sleep patterns have been shown to be not only linked to QoL impairment [21] and impaired memory functioning [1], but also to longer term health conditions such as a higher risk of depression [4], anxiety [24] and cardiovascular disorders [38].

The association between pruritus and QoL impairment was evident: overall, patients without pruritus experienced better skin disease-specific QoL and generic QoL in all domains, except the psychological and social domains, compared with patients with moderate to severe pruritus, confirming the effects on daily life [19, 22]. We investigated the prediction of sleep impairment by demographic, clinical and psychological variables. Higher trait anxiety appeared to be the most important variable in predicting sleep impairment. Anxiety can strongly impair sleep quality [35] and conversely, poor sleep may result in higher levels of anxiety [35].

Comorbid depression, but not the current depressive mood, predicted the use of sleeping medication and difficulties falling asleep. It has been reported that sleep disorders are a core symptom of depression [25]. The patients diagnosed with depression were treated accordingly and this may have resulted in their normalised mood, as measured using BDI. Insomnia has been reported as the most frequent residual symptom following remission from depression occurring in up to 51% of treatment responders [5, 7]. Additionally, sleep is reportedly affected by some antidepressants [39], and this may have resulted in impaired sleep in some of our patients who were diagnosed with, and treated for, depression. This may explain why BDI was unrelated to sleep quality, whereas the diagnosis of depression was.

Interestingly, many patients reported that their sleep difficulties were caused by pruritus, whereas neither pruritus intensity, nor presence of pruritus allowed for predictions of variance in sleep disturbances. This may be because, even though pruritus intensity was on average higher in these patients, its distribution was wide and overlapped with intensities of pruritus in many patients without sleep problems, and in those with sleep problems unrelated to pruritus. Thus, patients appeared to differ in their sensitivity to pruritus in relation to sleep disturbances, indicating that other variables such as the presence of PsA and depression may have a larger, more consistent impact on sleep patterns.

Diagnosis of PsA was associated with awakenings during sleep. Patients with uncontrolled PsA were not included in this study; however, degenerative changes of currently inactive and controlled PsA could still have resulted in pain leading to awakenings during the night [8]. Additionally, the prevalence of sleep disorders increases with age [40], which our study supports as higher age predicted sleep disturbances.

Questionnaire-based studies are useful in assessing the physical and mental characteristics of pruritus; however, this study has limitations. First, we included questions, which covered the most important domains of sleep disturbances, but we did not use a validated questionnaire for the assessment of sleep quality. Second, sleep disturbances and whether or not sleep problems were caused by pruritus were exclusively subjectively assessed by patients. We also cannot disregard the possibility that some patients could be suffering from undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA).

The strength of our study is that we collected comprehensive demographic, clinical (including clinical examination and history taken by a dermatologist) and psychometric data, which enabled us to evaluate a wide spectrum of factors for their potential to interfere with sleep in psoriasis. Further, we recorded pruritus intensity, to investigate the link between sleep and pruritus in psoriasis, and data on this link are still very limited.

In conclusion, pruritus in patients with psoriasis was frequent and led to sleep disturbances, as claimed by over one-third of patients with sleep problems and as evidenced by higher pruritus intensity in these patients and the higher rate of difficulties falling asleep in patients with pruritus. Patients with sleep problems suffered a lower generic QoL in all domains, indicating a need to address the issue of pruritus and sleep disorders in patients with psoriasis.

References

Altena E, Van Der Werf YD, Strijers RL, Van Someren EJ (2008) Sleep loss affects vigilance: effects of chronic insomnia and sleep therapy. J Sleep Res 17(3):335–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00671.x(Epub 2008/10/11)

Amatya B, Wennersten G, Nordlind K (2008) Patients' perspective of pruritus in chronic plaque psoriasis: a questionnaire-based study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 22(7):822–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02591.x

Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG (1988) Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory—25 years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 8(1):77–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P (1996) Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry 39(6):411–418 (Epub 1996/03/15)

Carney CE, Segal ZV, Edinger JD, Krystal AD (2007) A comparison of rates of residual insomnia symptoms following pharmacotherapy or cognitive-behavioral therapy for major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 68(2):254–260 (Epub 2007/03/06)

Finlay AY, Khan GK (1994) Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)–a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol 19(3):210–216

Franzen PL, Buysse DJ (2008) Sleep disturbances and depression: risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 10(4):473–481 (Epub 2009/01/28)

Gezer O, Batmaz I, Sariyildiz MA, Sula B, Ucmak D, Bozkurt M, Nas K (2017) Sleep quality in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Int J Rheum Dis 20(9):1212–1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.12505(Epub 2014/11/05)

Globe D, Bayliss MS, Harrison DJ (2009) The impact of itch symptoms in psoriasis: results from physician interviews and patient focus groups. Health Qual Life Outcomes 7:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-62

Gowda S, Goldblum OM, McCall WV, Feldman SR (2010) Factors affecting sleep quality in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 63(1):114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2009.07.003

Hawro M, Maurer M, Weller K, Maleszka R, Zalewska-Janowska A, Kaszuba A, Gerlicz-Kowalczuk Z, Hawro T (2017) Lesions on the back of hands and female gender predispose to stigmatization in patients with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 76(4):648–654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2016.10.040(e642, Epub 2017/01/11)

Hawro T, Miniszewska J, Chodkiewicz J, Sysa-Jedrzejowska A, Zalewska A (2007) Anxiety, depression and social support in patients with psoriasis. Przegl Lek 64(9):568–571

Hawro T, Ohanyan T, Schoepke N, Metz M, Peveling-Oberhag A, Staubach P, Maurer M, Weller K (2018) Comparison and interpretability of the available urticaria activity scores. Allergy 73(1):251–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13271(Epub 2017/08/18)

Jensen P, Zachariae C, Skov L, Zachariae R (2018) Sleep disturbance in psoriasis: a case-controlled study. Br J Dermatol 179(6):1376–1384. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16702(Epub 2018/04/29)

Kaaz K, Szepietowski JC, Matusiak L (2018) Influence of itch and pain on sleep quality in atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-3065(Epub 2018/10/12)

Kabashima K, Furue M, Hanifin JM, Pulka G, Wollenberg A, Galus R, Etoh T, Mihara R, Nakano M, Ruzicka T (2018) Nemolizumab in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: randomized, phase II, long-term extension study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2018.03.018(Epub 2018/05/13)

Kido-Nakahara M, Katoh N, Saeki H, Mizutani H, Hagihara A, Takeuchi S, Nakahara T, Masuda K, Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Nakagawa H, Omoto Y, Matsubara K, Furue M (2015) Comparative cut-off value setting of pruritus intensity in visual analogue scale and verbal rating scale. Acta Derm Venereol 95(3):345–346. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1972(Epub 2014/09/18)

Krause K, Kessler B, Weller K, Veidt J, Chen SC, Martus P, Church MK, Metz M, Maurer M (2013) German version of ItchyQoL: validation and initial clinical findings. Acta Derm Venereol 93(5):562–568. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1544(Epub 2013/03/16)

Krueger G, Koo J, Lebwohl M, Menter A, Stern RS, Rolstad T (2001) The impact of psoriasis on quality of life: results of a 1998 National Psoriasis Foundation patient-membership survey. Arch Dermatol 137(3):280–284

Lavery MJ, Stull C, Nattkemper LA, Sanders KM, Lee H, Sahu S, Valdes-Rodriguez R, Chan YH, Yosipovitch G (2017) Nocturnal pruritus: prevalence, characteristics, and impact on ItchyQoL in a chronic itch population. Acta Derm Venereol 97(4):513–515. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2560(Epub 2016/11/03)

Leger D, Scheuermaier K, Philip P, Paillard M, Guilleminault C (2001) SF-36: evaluation of quality of life in severe and mild insomniacs compared with good sleepers. Psychosom Med 63(1):49–55 (Epub 2001/02/24)

Mease PJ, Menter MA (2006) Quality-of-life issues in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: outcome measures and therapies from a dermatological perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol 54(4):685–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2005.10.008(Epub 2006/03/21)

Mrowietz U, Chouela EN, Mallbris L, Stefanidis D, Marino V, Pedersen R, Boggs RL (2015) Pruritus and quality of life in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: post hoc explorative analysis from the PRISTINE study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29(6):1114–1120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.12761(Epub 2014/11/05)

Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA (2007) Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep 30(7):873–880 (Epub 2007/08/09)

Nutt D, Wilson S, Paterson L (2008) Sleep disorders as core symptoms of depression. Dialog Clin Neurosci 10(3):329–336 (Epub 2008/11/05)

O'Neill JL, Chan YH, Rapp SR, Yosipovitch G (2011) Differences in itch characteristics between psoriasis and atopic dermatitis patients: results of a web-based questionnaire. Acta Derm Venereol 91(5):537–540. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-1126

Reich A, Chatzigeorkidis E, Zeidler C, Osada N, Furue M, Takamori K, Ebata T, Augustin M, Szepietowski JC, Stander S (2017) Tailoring the cut-off values of the visual analogue scale and numeric rating scale in itch assessment. Acta Derm Venereol 97(6):759–760. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2642(Epub 2017/02/23)

Reich A, Hrehorów E, Szepietowski JC (2010) Pruritus is an important factor negatively influencing the well-being of psoriatic patients. Acta Derm Venereol 90(3):257–263. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-0851

Roth T (2000) Diagnosis and management of insomnia. Clin Cornerstone 2(5):28–38 (Epub 2000/06/30)

Sampogna F, Gisondi P, Melchi CF, Amerio P, Girolomoni G, Abeni D, Investigators IDIMPRoVE (2004) Prevalence of symptoms experienced by patients with different clinical types of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 151(3):594–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06093.x

Shahwan KT, Kimball AB (2017) Itch intensity in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis versus atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 76(6):1198–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.002(e1191, Epub 2017/05/20)

Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell KA, Group W (2004) The World Health Organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 13(2):299–310

Smolensky MH, Portaluppi F, Manfredini R, Hermida RC, Tiseo R, Sackett-Lundeen LL, Haus EL (2015) Diurnal and twenty-four hour patterning of human diseases: acute and chronic common and uncommon medical conditions. Sleep Med Rev 21:12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.005(Epub 2014/08/19)

Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg P-R, Jacobs GA (1983) Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto

Staner L (2003) Sleep and anxiety disorders. Dialog Clin Neurosci 5(3):249–258 (Epub 2003/09/01)

Suilmann T, Zeidler C, Osada N, Riepe C, Stander S (2018) Usability of validated sleep-assessment questionnaires in patients with chronic pruritus: an interview-based study. Acta Derm Venereol. https://doi.org/10.2340/00015555-2947(Epub 2018/04/25)

Szepietowski JC, Reich A, Szepietowski T (2005) Emollients with endocannabinoids in the treatment of uremic pruritus: Discussion of the therapeutic options. Ther Apheresis Dial 9(3):277–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1774-9987.2005.00271.x

Vgontzas AN, Liao D, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP, Vela-Bueno A (2009) Insomnia with objective short sleep duration is associated with a high risk for hypertension. Sleep 32(4):491–497 (Epub 2009/05/06)

Wichniak A, Wierzbicka A, Walecka M, Jernajczyk W (2017) Effects of antidepressants on sleep. Curr Psychiatry Rep 19(9):63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-017-0816-4(Epub 2017/08/10)

Wolkove N, Elkholy O, Baltzan M, Palayew M (2007) Sleep and aging: 1 Sleep disorders commonly found in older people. CMAJ 176(9):1299–1304. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060792 (Epub 2007/04/25)

Yosipovitch G, Goon A, Wee J, Chan YH, Goh CL (2000) The prevalence and clinical characteristics of pruritus among patients with extensive psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 143(5):969–973

Yosipovitch G, Goon AT, Wee J, Chan YH, Zucker I, Goh CL (2002) Itch characteristics in Chinese patients with atopic dermatitis using a new questionnaire for the assessment of pruritus. Int J Dermatol 41(4):212–216

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the editorial assistance provided by Gillian Brodie of Orbit Medical Communications, Cambridge, UK, with the help of the urticaria network e.V. (UNEV, https://www.urtikaria.net). We also thank Professor Andrzej Kaszuba for enabling us recruitment of patients at the Department of Dermatology, Pediatric Dermatology and Oncology, Medical University of Łódź, Łódź, Poland.

Funding

Intramural funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

MH, AZJ, KW, MM and MM have no relevant conflicts of interest. TH has served on an advisory board for Galderma.

Ethical approval

All the procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Łódź; approval no. RNN/240/09/KE) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hawro, T., Hawro, M., Zalewska-Janowska, A. et al. Pruritus and sleep disturbances in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res 312, 103–111 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-019-01998-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00403-019-01998-7