Abstract

Purpose

Opioids are a mainstay for pain management after total joint arthroplasty (TJA). The prevalence and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after TJA are important to understand to help slow the opioid epidemic. We aim to summarize and evaluate the prevalence and time trend of prolonged opioid use after TJA and pool its risk factors.

Methods

Following the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis statement, we systematically searched PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and EMBASE, etc. from inception up to October 1, 2019. Cohort studies reporting risk factors for prolonged opioids use (≥ 3 months) after TJA were included. Studies characteristics, risk ratios (RR), and prevalence of prolonged opioid use were extracted and synthesized.

Results

A total of 15 studies were published between 2015 and 2019, with 416,321 patients included. 12% [95%CI 10–14%] of patients had prolonged opioid use after TJA and its time trend was associated with median enrollment years (P = 0.0013). Previous opioid use (RR = 1.73; P < 0.001), post-traumatic stress disorder (RR = 1.34; P < 0.001), benzodiazepine use (RR = 1.38; P < 0.001), tobacco abuse (RR = 1.26; P < 0.001), fibromyalgia (RR = 1.51; P < 0.001), and back pain (RR = 1.34; P < 0.001) were the largest effective risk factors for prolonged use of opioids.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis determining the risk factors of prolonged opioid use and characterizing its rate and time trend in TJA. Understanding risk factors for patients with higher potential for prolonged opioids use can be used to implement appropriate management strategies, reduce unsafe opioid prescriptions, and decrease the risk of prolonged opioid use after TJA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study shows that the global age-standardized prevalence of knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA) has reached 3.8% and 0.85%, respectively [1]. In the United States, more than 27 million adults suffer from OA [2], affecting almost one-third of adults aged more than 65 years. Clinicians generally manage them with exercise, education, physiotherapy, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cautious prescription of opioids to reduce pain and improve functional ability. Recently, the decreased threshold of opioid administration led to over-prescription and dependence of opioids [3] in OA patients, the number of opioid prescriptions and opioid-related overdose death have quadrupled from 1999 to 2014, resulting in public health emergencies called opioid crisis [4].

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA), as one of the most common and successful surgical procedure for OA, is successfully used to reduce osteoarthritis pain, increase mobility, and improve life quality, in which total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) are expected to grow 85% to 1.26 million procedures and 71% to 635,00 procedures to 2030 in the United States, respectively [5]. Although analgesic demand should decrease accordingly after them, due to factors including lower back pain [6], sustained surgery-related pain [7], and drug addiction [8], etc., long-term opioids use either before or after TJA is still quite common, 14% patients took opioids before TKA, and 3% opioid naïve (no opioids use preoperative) patients begin continued taking opioids more than 12 months [9] as a cohort study reported.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons make a statement entitled “Opioid Use, Misuse, and Abuse in Orthopaedic Practice” and recommend identifying patients at higher risk of prolonged opioid use and establishing a valid predictive model [10]. Therefore, it has become an orthopaedic central focus to reveal the risk factors of persistent and chronic use of opioids and develop new chronic drug use for this group as required by the guidelines. We aim to (1) pool the risk factors of long-term opioid use following TJA, and (2) assess whether a time trend exits in prolonged opioids use rate after TJA.

Methods

This meta-analysis consists of two sub-reviews: (1) the worldwide pooled rate of prolonged opioid use changing in enrollment years after TJA; (2) the pooled risk ratios (RR) of risk factors for long-term opioid use after TJA, all according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) Statement (Appendix 3) and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) Group guidelines.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science, Ovid, and Medline from the inception up to October 10, 2019 with the following terms: (“opioid” OR “analgesics” OR “fentanyl” OR “hydrocodone” OR “hydromorphone” OR “levorphanol” OR “meperidine” OR “methadone OR” “morphine OR” “opiate” OR “opiates” OR “opioids” OR “oxycodone” OR “oxymorphone” OR “ pentazocine” OR “propoxyphene” OR “sufentanil” OR “tramadol”) AND (“arthroplasty” OR “knee replacement” OR “hip replacement” OR “shoulder replacement”) AND (“risk ratio” OR “odds ratio” OR “predictor” OR “protective factors” OR “risk” OR “hazard ratio” OR “risk factor” OR “ratio”) to identify relevant studies, and we also reviewed included studies, correlative reviews and published meta-analysis references to identify additional potential original studies.

Inclusion criteria

Two investigators (W.L.M and L.M.Y) independently screened all studies and included any study that reported the associations between prolonged opioids use after TJA and the following risk factors: demographics, mental diseases, hematological diseases, respiratory diseases, circulatory diseases, endocrine diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, digestive diseases, urinary diseases, previous medication, abuse, and pain history. According to the guidelines of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), opioid treatment is rarely needed to be taken more than 7 days, and “prolonged opioid use” is generally defined as time spans of > 2 months. Therefore, prolonged opioid use was defined as use of opioids more than 3 months after TJA in this analysis, all studies that defined prolonged opioid use as less than 3 months were excluded. Besides, we also included relevant studies reporting the prevalence of long-term opioid use after TJA.

Assessment of risk of bias

9-Star Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied to assess the risk of bias for eligible studies consists of representativeness, ascertainment of exposure, group comparability, follow-up, etc., and we also use GRADE system by Grade Pro (https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/) to assess the quality of evidence. Disagreements in above were resolved by discussion between the two investigators (W.L.M and L.M.Y).

Data extraction

We extracted data according to a pre-designed standardized table, including author, publication year, study design, sample size, the proportion of male, age, follow-up duration, type of surgery, criteria for prolonged use of opioids, risk factors, and research conclusions. We further extracted the relative risk (risk ratio and relative risk ratio) of risk factors and a 95% confidence interval and used the maximally adjusted data when it was available. For studies that reported several follow-up time points, we used the data with the longest follow-up.

Data analysis

In this meta-analysis, we pooled and analyzed the relative risks of risk factors reported at least twice in the eligible studies. Inclusion studies in this analysis were all cohort studies, so risk ratios (RR) and a 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to assess the effect size for risk factors. We converted the odds ratios (OR) and original data to RR to calculate the pooled effect size. It is worth mentioning that to avoid the potential influence of confounding factors, we also excluded studies without adjustments for confounding factors including age, sex, BMI, etc., when performing pooled analysis. I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity among studies, and the fixed-effect model was used when I2 < 50% and the random-effect model was used when heterogeneity ≥ 50%. We finally analyzed 41 risk factors, and to facilitate review and reading, they were divided into following 11 groups: demographics, mental diseases, hematological diseases, respiratory diseases, circulatory diseases, endocrine diseases, musculoskeletal diseases, previous medication, abuse, and pain history diseases. Also, to explore the temporal trend of long-term use of opioids in recent years, we assessed the impact of time on the prevalence of long-term use of opioids using meta-regression analysis with reml method.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted multiple subgroup analyses by opioid use durations, countries of origin, and patient’s middle enrollment time (i.e., the year that was in the middle of the study duration) to explore potential sources of significant I2 and removed outliers to minimize heterogeneity. When heterogeneity is still significant, the possibility of publishing bias and selective reporting was tested by Egger’s linear regression, A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered with statistical significance.

Above analyses were all performed by Stata/SE 15.1 for Mac (Version 08).

Results

Literature and study characteristics

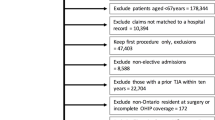

The flowchart in Fig. 1 shows the selection process of eligible studies. The systematic electronic database search identified 2394 citations, after removing 1117 duplicates, the remaining 1277 were reviewed by titles and abstracts, of which 49 were examined in the full text, and 1178 were excluded. We finalized included 15 cohort studies, and 22 were excluded, because they were not total joint arthroplasty; seven were excluded, because they were conference articles; five were excluded, because their prolonged opioids use was shorter than three months.

We included 15 studies with 416,321 patients in the meta-analysis publishing between 2015 and 2019 with sample sizes ranged from 338 to 120,080. Follow-up duration ranged from 3 to 12 months. Figure 1 shows the selection procession of eligible studies, and characteristics of included studies are described in Table 1. Quality of studies assessed by NOS and GRADE evidence level assessed by Grade pro are listed in Appendix 1 and 2, respectively. The mean NOS score was 6.2 (maximum 9), suggesting that this meta-analysis included high-quality cohort studies.

Pooled rate of long-term opioid use and time trend after TJA

Eleven out of fifteen included studies reported the rate of prolonged use of opioid after total joint arthroplasty. Meta-analysis demonstrated that the pooled rate of long-term opioid use was 12% [95%CI 10–14%] (Fig. 2). However, a considerable heterogeneity should be taken into consideration among different studies (I2 = 99.8%). Therefore, we conducted the meta-regression to evaluate the potential effects of patients’ enrollment time, and result shows that the rate of long-term opioid use was significant associated with median enrollment years (meta-regression, P = 0.013) (Fig. 3) which means that the prevalence rates of prolonged opioid use were sustained rise in recent years.

Risk factors for long-term opioid use after TJA

For the classified risk factors, age (young/old), sex (female/male), knee vs hip, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), deficiency anemia, coagulopathy, chronic lung diseases, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes, fibromyalgia, previous opioid use, previous NSAID (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) use, previous benzodiazepine use, previous antidepressant use, tobacco abuse, substance abuse, back pain, margarine, and liver diseases were significant associated with prolonged use of opioids (Table 2).

Among these factors, previous opioid use (> 3 months), PTSD, benzodiazepine use, tobacco abuse, fibromyalgia, and back pain were the most important predictors for long-term opioid use.

Due to Egger’s test revealed a publication bias of previous opioids use (P = 0.0023) and high heterogeneity, we use Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill methods on it (RR = 1.219, 95%CI: 1.050 to 1.389 P < 0.001 with two studies estimated on the left side) and the results were still showed positive significance. Although Egger’s test also revealed publication bias for PTSD, NSAID, and Renal Failure, they could not be calculated for trim-and-fill method, because only three studies reported these variables.

Discussion

It is predicted that a total of more than 3.48 million TKAs and nearly 600 thousand THAs will be performed by 2030, which with a predicted rate of long-term opioid use of 12%, which means that there might may be more than 250 thousand new long-term opioid users in the USA per years over this period [24]. Thereby the rapid increase in chronic opioid use should be taken into seriously consideration, particularly in clinical orthopaedic surgeons due to the severe impact on patient clinical outcomes, morbidity, and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery [26, 27]. Therefore, the selection of such patients, improvement of preoperative medical optimization, multimodal pain management strategy, and how to properly manage perioperative opioid use patterns is an increasingly common topic. Although the existing studies link chronic opioids use with the adverse clinical outcomes after TJA, the prescription and dispensing patterns of opioids is still increasing [3]. Based on above reasons, it is necessary to further identify patients at risk of long-term opioids use to implement appropriate perioperative management strategies and reduce unsafe opioid prescriptions. This may include a better assessment of comorbid pain conditions and, such as tapering high-dose opioids to a lower dose opioid before joint replacement surgery. Modifying opioid use before surgery patients may have led to better outcomes as the risk of prolonged opioid use will also should be improved.

We found that nearly 12% of patients still use opioids 3 months after TJA. Obviously, this is higher than a previous meta-analysis examining’ pooled rate after trauma or surgery (approximately 4%) [28]. Besides, we also observed that from 2001 to 2013, the prevalence rate of long-term opioids usages has increased significantly, which makes it imperative to understand the risk factors of prolonged opioid use.

Based on critical evidence of our study shows that previous opioid use (> 3 months), PTSD, benzodiazepine/tobacco abuse, fibromyalgia, and back pain have the most substantial influence on long-term opioid use. Interestingly, joint pain and fracture contusion pain were not associated prolonged opioid use, which may be caused by the resolution of arthritic pain of these operated joints, suggesting that joint pain and chronic joint diseases resulting in TJA had no association with prolonged opioid use after it.

Most notably, our analysis identified the preoperative chronic opioids use (> 3 months) as the most influential risk factors for long-term opioids use after TJA. Similar to previous studies, Goesling et al.’s [24] study shows high-dose opioids use patients accounting more than 80% predicted of being prolonged opioid use after 6 months in TKA/THA, which might due to that chronic opioid users produce opioids dependent or self-treatment of distress or may develop opioid-induced hyperalgesia, making it challenging to stop opioid therapy even after TJA. Thereby, further stratification of patients according to the reasons of taking opioids is a crucial next step in understanding and intervening the long-term opioid use after TJA.

In psychiatric diseases, we found that depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, and PTSD are all associated with prolonged opioid use. Unlike previous pooled data about trauma and surgery patients [28], the use of antidepressants and benzodiazepines also increases the risk of prolonged opioid use after TJA. Previous studies [13, 29] revealed that the effect of opioids as pain management therapy in patients with the psychiatric disease is less responsive, resulting in more frequent and more prolonged opioid use. Therefore, pain management gradually become a challenge for this population. Moreover, the simultaneous use of opioids and benzodiazepines should be avoided or minimized because of the increasing risk of sustained opioid use and potentially fatal overdose [13].

Tobacco abuse has a significant association with prolonged opioid use, because the efficacy of opioids is generally diminished in this population. Eriksen et al.’s [30] study found that long-term exposure to tobacco and nicotine smoke could result in acetylcholine receptor (analgesic effect) persistent desensitization and tolerance which means that long-term smokers are more susceptible to severe and abiding pain compared with nonsmokers.

There are also several types of preoperative pain histories associated with a higher risk of long-term opioid use. Back pain and fibromyalgia were the most common symptoms associated with it. Patients diagnosed with back pain before TJA were nearly 1.5 times more likely to continue prolonged opioid use after TJA.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to determine the risk factors of long-term opioid use after TJA and characterize the rate and time trend of prolonged opioid use in TJA patients. In addition, all eligible studies were cohort studies, excluding univariate analysis and adjusting confounding factors as much as possible, expanding the previous research on surgery or trauma patients [28] and newly incorporating multiple systemic diseases including circulation, respiratory, hematological diseases, etc.

This meta-analysis should be interpreted in combination with its limitations. First of all, we cannot explain several outcomes’ source of substantial heterogeneity through sensitivity analysis, including subgroup analysis, etc. To avoid publication bias caused by heterogeneity and give a better evidence evaluation of reported risk factors, Tweedie’s trim-and-fill methods were performed which aimed to determine the model stability and grade of evidence were also assessed and reported. Second, although all included studies’ criteria for long-term opioid use were more than 3 months, different studies’ thresholds for it were various, potentially explaining the source of the aforementioned heterogeneity. Third, some of the included studies did not separately report the risk factors for new opioid users and continuing users, which means that we could not analysis the prevalence and risk factors in the above group separately due to the limitation of original data and may suffer from selection bias.

In conclusion, our pooled rate shows that almost 12% patients are persistent opioid use after TJA, critical and high-quality evidence demonstrated preoperative factors associated with persistent opioid use included previous opioid use (> 3 months), PTSD, benzodiazepine/tobacco abuse, fibromyalgia, and back pain. If the risk stratification, optimization scheme, and active encouragement of orthopaedic clinicians and high-risk patients discussing pain expectations before TJA are formulated based on above factors, the use of opioids and the occurrence of opioid dependence may be further improved. Meanwhile, it is equally important that orthopaedic clinicians should consciously avoid treating OA patients with opioids preoperatively, as the existing available evidence [31, 32] shows that these medications are ineffective and even lead to a more difficult rehabilitation process and lower satisfaction after TJA. Future studies should focus on assessing potential strategies to reduce opioid use to alleviate long-term opioid prescription, especially in preoperative chronically taking opioid patients.

References

Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, Nolte S, Ackerman I, Fransen M, Bridgett L, Williams S, Guillemin F, Hill CL, Laslett LL, Jones G, Cicuttini F, Osborne R, Vos T, Buchbinder R, Woolf A, March L (2014) The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 73(7):1323–1330. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763

Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, Liang MH, Kremers HM, Mayes MD, Merkel PA, Pillemer SR, Reveille JD, Stone JH (2008) Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 58(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.23177

Kendrick BJ, Bottomley NJ, Gill HS, Jackson WF, Dodd CA, Price AJ, Murray DW (2012) A randomised controlled trial of cemented versus cementless fixation in Oxford unicompartmental knee replacement in the treatment of medial gonarthrosis using radiostereometric analysis. Osteoarthr Cartil 20:S36–S37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2012.02.566

Health UDo, Services H (2018) HHS acting secretary declares public health emergency to address national opioid crisis. HHS gov https://www.hhsgov/about/news/2017/10/26/hhs-acting-secretary-declares-public-health-emergency-address-national-opioid-crisishtml. Published May 23

Sloan M, Premkumar A, Sheth NP (2018) Projected volume of primary total joint arthroplasty in the US, 2014 to 2030. J Bone Jt Surg Am 100(17):1455–1460. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.17.01617

Vogt MT, Kwoh CK, Cope DK, Osial TA, Culyba M, Starz TW (2005) Analgesic usage for low back pain: impact on health care costs and service use. Spine 30(9):1075–1081. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000160843.77091.07

Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P (2012) What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2(1):e000435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435

Hah JM, Sharifzadeh Y, Wang BM, Gillespie MJ, Goodman SB, Mackey SC, Carroll IR (2015) Factors associated with opioid use in a cohort of patients presenting for surgery. Pain Res Treat 2015:829696. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/829696

Franklin PD, Karbassi JA, Li W, Yang W, Ayers DC (2010) Reduction in narcotic use after primary total knee arthroplasty and association with patient pain relief and satisfaction. J Arthroplasty 25(6 Suppl):12–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2010.05.003

Surgeons AAoO (2018) Information statement: opioid use, misuse, and abuse in orthopaedic practice. 2015. October https://www.aaos.org/uploadedFiles/PreProduction/About/Opinion_Statements/advistmt/1045%20Opioid%20Use,%20Misuse,%20and%20Abuse%20in%20Practice pdf. Accessed

Prentice HA, Inacio MCS, Singh A, Namba RS, Paxton EW (2019) Preoperative risk factors for opioid utilization after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Jt Surg Am 101(18):1670–1678. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.18.01005

Khazi ZM, Lu Y, Patel BH, Cancienne JM, Werner B, Forsythe B (2020) Risk factors for opioid use after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 29(2):235–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2019.06.020

Kim KY, Anoushiravani AA, Chen KK, Roof M, Long WJ, Schwarzkopf R (2018) Preoperative chronic opioid users in total knee arthroplasty-which patients persistently abuse opiates following surgery? J Arthroplasty 33(1):107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.041

Namba RS, Singh A, Paxton EW, Inacio MCS (2018) patient factors associated with prolonged postoperative opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 33(8):2449–2454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.068

Rao AG, Chan PH, Prentice HA, Paxton EW, Navarro RA, Dillon MT, Singh A (2018) Risk factors for postoperative opioid use after elective shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 27(11):1960–1968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2018.04.018

Politzer CS, Kildow BJ, Goltz DE, Green CL, Bolognesi MP, Seyler TM (2018) Trends in opioid utilization before and after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 33(7s):S147–S153.e141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.060

Hadlandsmyth K, Vander Weg MW, McCoy KD, Mosher HJ, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Lund BC (2018) Risk for prolonged opioid use following total knee arthroplasty in veterans. J Arthroplast 33(1):119–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.022

Bedard NA, Pugely AJ, Dowdle SB, Duchman KR, Glass NA, Callaghan JJ (2017) Opioid use following total hip arthroplasty: trends and risk factors for prolonged use. J Arthroplast 32(12):3675–3679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.08.010

Dwyer MK, Tumpowsky CM, Hiltz NL, Lee J, Healy WL, Bedair HS (2018) Characterization of post-operative opioid use following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplast 33(3):668–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.10.011

Bedard NA, Pugely AJ, Westermann RW, Duchman KR, Glass NA, Callaghan JJ (2017) Opioid use after total knee arthroplasty: trends and risk factors for prolonged use. J Arthroplast 32(8):2390–2394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2017.03.014

Hansen CA, Inacio MCS, Pratt NL, Roughead EE, Graves SE (2017) Chronic use of opioids before and after total knee arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. J Arthroplast 32(3):811–817.e811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arth.2016.09.040

Sun EC, Bateman BT, Memtsoudis SG, Neuman MD, Mariano ER, Baker LC (2017) Lack of association between the use of nerve blockade and the risk of postoperative chronic opioid use among patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: evidence from the marketscan database. Anesth Analg 125(3):999–1007. https://doi.org/10.1213/ane.0000000000001943

Inacio MC, Hansen C, Pratt NL, Graves SE, Roughead EE (2016) Risk factors for persistent and new chronic opioid use in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 6(4):e010664. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010664

Goesling J, Moser SE, Zaidi B, Hassett AL, Hilliard P, Hallstrom B, Clauw DJ, Brummett CM (2016) Trends and predictors of opioid use after total knee and total hip arthroplasty. Pain 157(6):1259–1265. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000516

Kim SC, Choudhry N, Franklin JM, Bykov K, Eikermann M, Lii J, Fischer MA, Bateman BT (2017) Patterns and predictors of persistent opioid use following hip or knee arthroplasty. Osteoarthr Cartil 25(9):1399–1406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2017.04.002

Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT (2015) Preoperative opioid misuse is associated with increased morbidity and mortality after elective orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 473(7):2402–2412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4173-5

Morris BJ, Laughlin MS, Elkousy HA, Gartsman GM, Edwards TB (2015) Preoperative opioid use and outcomes after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 24(1):11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2014.05.002

Mohamadi A, Chan JJ, Lian J, Wright CL, Marin AM, Rodriguez EK, von Keudell A, Nazarian A (2018) Risk factors and pooled rate of prolonged opioid use following trauma or surgery: a systematic review and meta-(regression) analysis. J Bone Jt Surg Am 100(15):1332–1340. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.17.01239

Workman EA, Hubbard JR, Felker BL (2002) Comorbid psychiatric disorders and predictors of pain management program success in patients with chronic pain. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 4(4):137–140. https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v04n0404

Eriksen WB, Brage S, Bruusgaard D (1997) Does smoking aggravate musculoskeletal pain? Scand J Rheumatol 26(1):49–54. https://doi.org/10.3109/03009749709065664

Nuesch E, Rutjes AW, Husni E, Welch V, Juni P (2009) Oral or transdermal opioids for osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev 4:Cd003115. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003115.pub3

Smith SR, Deshpande BR, Collins JE, Katz JN, Losina E (2016) Comparative pain reduction of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids for knee osteoarthritis: systematic analytic review. Osteoarthr Cartil 24(6):962–972. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2016.01.135

Funding

This study was supported through grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802210 and 81672219), National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Z20191008), the Key Project of Sichuan Science and Technology Department (2018SZ0223 and 2018SZ0250), and the National Clinical Research Center for Geriatrics, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Z2018B20).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, L., Li, M., Zeng, Y. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 141, 907–915 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03486-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-020-03486-4