Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the healing rate of repaired meniscus and functional outcomes of patients who received all-inside meniscal repair using sutures or devices with concomitant arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction.

Materials and methods

Among the patients who have ACL tear and posterior horn tear of medial or lateral meniscus, 61 knees who received all-inside repair using sutures (suture group, n = 28) or meniscal fixation devices (device group, n = 33) with concomitant ACL reconstruction during the period from January 2012 to December 2015, followed by second-look arthroscopy, were retrospectively reviewed. Healing status of the repair site was assessed by second-look arthroscopy. Through the clinical assessment, clinical success (negative medial joint line tenderness, no history of locking or recurrent effusion, and negative McMurray test) rate of the repaired meniscus and functional outcomes (International Knee Documentation Committee subjective score and Lysholm knee score) was evaluated.

Results

In a comparison of healing status of repaired meniscus evaluated by second-look arthroscopy, suture group had 23 cases of complete healing (82.1%), 4 cases of incomplete healing (14.3%), and 1 case of failure (3.6%). Device group had 18 cases of complete healing (54.5%), 4 cases of incomplete healing (24.2%), and 7 cases of failure (21.2%) (p = 0.048). Clinical success rate of the meniscal repair was 89.3% (25 cases) and 81.8% (27 cases) in suture group and device group, respectively (p = 0.488). No significant difference of functional outcomes was observed between the two groups (p > 0.05, both parameters).

Conclusions

Among the patients who received meniscal repair with concomitant ACL reconstruction, suture group showed better healing status of repaired meniscus based on the second-look arthroscopy than device group. However, no significant between-group difference of clinical success rate and functional outcomes was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Menisci play a critical role in maintaining the biomechanical stability at the knee joint, by contributing to load transmission and shock absorption [1,2,3]. Meniscectomized knees have been shown to develop early arthritic changes and it is broadly accepted that meniscal tear should be repaired if possible [1, 2, 4]. In particular, repair should be primarily considered in young patients with traumatic meniscal tears. Previous studies have found that 40–60% of patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries have concomitant meniscal tears [5,6,7,8,9].

Repair techniques for meniscal tear can be largely categorized as inside-out, outside-in, and all-inside repair techniques [2]. The choice of repair technique is guided by the location of meniscal tear, the tear pattern, and the preference of the surgeon [10]. Inside-out or all-inside repair techniques are frequently used for repair of meniscal posterior horn tears. All-inside repair technique offers the advantage of low risk of damage to the posterior neurovascular structure, compared to the inside-out technique [11,12,13]. There are two methods for the all-inside repair technique. One involves the use of sutures to repair the torn meniscal tissue and the second technique involves the use of meniscal fixation devices. Although the use of sutures offers the advantage of the possibility of vertically oriented sutures, it is a time-consuming and technically demanding technique. Hence, many types of meniscal fixation devices are widely used in clinical practice [14,15,16].

Several studies have reported the clinical outcomes of all-inside repair technique using sutures or meniscal fixation devices [11, 17,18,19,20,21,22,23]. However, there is no consensus on the superiority of one technique over the other regarding clinical outcomes [24,25,26]. Furthermore, a few studies have compared the healing status of the menisci repaired with the two techniques using objective methods, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or second-look arthroscopy. Choi et al. [15] reported the healing rates and functional outcomes of all-inside meniscal repair using either sutures or the meniscal fixation device using MRI; however, virtually, no study has compared the two techniques using the second-look arthroscopy. Hence, comparing the two types of all-inside repair techniques based on second-look arthroscopy is likely to provide meaningful insights.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the healing rate of repaired meniscus and the functional outcomes of patients who received all-inside meniscal repair using sutures or devices with concomitant arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. It was assumed that the technique involving the use of sutures would provide better healing rate and functional outcomes than that achieved with the use of meniscal fixation devices.

Materials and methods

Patients

This study was approved by the institutional review board of our institution. During the period from May 2012 to December 2016, 202 patients with ACL tear received arthroscopic ACL reconstruction; of these, 96 patients had concomitant lateral or medial meniscal tear. Among these, 85 patients received meniscal repair. The inclusion criteria for this study were (1) primary ACL reconstruction, (2) red–red or red–white zone tear of lateral or medial meniscal posterior horn, (3) all-inside repair, (4) implementation of second-look arthroscopy, and (5) follow-up duration > 2 years.

The exclusion criteria were (1) multiple ligament injury, (2) meniscectomy for meniscal tear, (3) revision ACL reconstruction, (4) failed ACL reconstruction, (5) inside-out or outside-in repair of meniscal tear, (6) no implementation of second-look arthroscopy, and (7) follow-up duration < 2 years.

As the instability of knee joint can affect the healing process of the repaired meniscus, patients who had recurrence of laxity after ACL reconstruction or those with traumatic rupture of ACL graft were classified as failed ACL reconstruction and were excluded from this study. Failure of the primary ACL reconstruction was defined as grade 2 in Pivot shift test or grade 2 in Lachman test. Finally, 61 patients (61 knees) who qualified the study-selection criteria were enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Out of the 61 knees, 28 knees were treated with suture technique (suture group) using No. 1 polydioxanone suture (PDS; Ethicon, Somerville, NJ). For the remaining 33 knees (device group), meniscal fixation device (FasT-Fix, Smith & Nephew Endoscopy, Andover, MA) was used. The average age of patients in the suture and device groups was 31.0 ± 10.4 years and 29.4 ± 8.6 years, respectively. Mean time elapsed between meniscal repair and the second-look arthroscopy was 16.0 ± 4.0 months and 16.5 ± 4.2 months, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the demographic data and intraoperative findings in the two groups.

Surgical technique

All the surgeries were implemented by a single senior surgeon. ACL reconstruction was performed after the meniscal repair. All the patients underwent ACL reconstruction using the outside-in technique. Autologous quadrupled hamstring tendons or allografts (tibialis posterior or tibialis anterior) were used as grafts. The femoral side of the graft was fixed using Tightrope™ (Arthrex). The tibial side of the graft was fixed using a bioabsorbable interference screw (Smith and Nephew) and was post-tied to the 4.5 mm cortical screw.

Routine arthroscopic examination was performed with a 30° oblique arthroscope in the anterolateral portal and a probe in the anteromedial portal. The meniscus was carefully observed through probing. Repair technique on the meniscal tear was determined after evaluation of the location, extent, and type of meniscal tear and the quality of meniscal tissue.

The following procedure was performed in the suture group. Posterolateral or posteromedial portal was created in patients with confirmed tear of the posterior horn of the lateral or medial meniscus. Tear site was debrided by inserting a motorized shaver through the posterolateral or the posteromedial portal. Meniscal tear site was repaired using suture hook (Linvatec, Largo, FL). From the anterolateral or anteromedial portal at the intercondylar notch, a 70° arthroscope was introduced into the posteromedial or posterolateral compartment. After checking the tear site via the arthroscope, the tip of the suture hook was penetrated into the peripheral fragment from superior to inferior direction. After confirming the exit of the tip of the suture hook from the tear site, the central fragment was sutured in an inferior to superior direction. The two suture ends were brought outside the knee joint using the suture retriever and a sliding knot (SMC knot) and 2–3 additional simple knots were created while observing the approximation of the tear site (Fig. 2a and b).

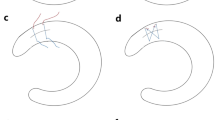

In the device group, the menisci were repaired using the FasT-Fix according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The FasT-Fix delivery needle with a split cannula was introduced into the knee joint through the anterolateral or anteromedial portal. After taking out the split cannula, the surgeon penetrated the FasT-Fix delivery needle into the peripheral segment. After advancing the FasT-Fix delivery needle to the end of the depth-penetration limiter, the needle was gently withdrawn from the outer segment. Next, the central fragment was penetrated by the needle and the second toggle anchor was advanced by sliding forward the trigger. After retrieving the delivery needle, both the suture ends were gently pulled for approximation of the tear site. By checking the approximation of the tear site, tension was imposed on the prettied self-sliding knot using the knot pusher–cutter and, then, the knot was cut. Either suturing or the use of FasT-Fix was performed vertically at intervals of 5–8 mm interval. Some sutures were placed obliquely or horizontally if vertical suture was not feasible due to difficult approach of the delivery needle (Fig. 3a and b). MCL release was accomplished using an 18-gauge needle in cases where the medial compartment of the knee joint was too tight for suturing (i.e., pie crust technique). This procedure was carefully conducted, such that the joint space was extended for approximately 2–3 mm. There was no absolute standard for the choice between the use of sutures or meniscal fixation device for meniscal repair. However, use of meniscal fixation device was preferred when access to the tear site through the posterior portal was deemed difficult or when knee joint was too tight to allow the use of suture hook.

Rehabilitation

The post-ACL reconstruction rehabilitation protocol was identical in the two groups. ACL hinge brace was applied to all the patients, and quadriceps exercises and straight leg raise were implemented immediately after the surgery. For 3 weeks after the surgery, the range of motion at the knee joint was restricted to between 0° and 30° under the condition of wearing brace. Partial weight-bearing with use of crutches was allowed. Flexion exercises were implemented from 3 weeks after the surgery with a gradual increase in the range of motion. Full weight-bearing was allowed 6 weeks after the surgery and brace was removed 2 months after the surgery. Return to sports was allowed at the tenth postoperative month for patients whose muscle strength was > 80% of that in the contralateral lower limb.

Evaluation

The Lachman test, pivot shift test, and stress X-ray at the time of out-patient visit immediately before the implementation of second-look arthroscopy were used to evaluate stability of the reconstructed ACL. The criteria for the success of meniscal repair included negative medial joint line tenderness, no history of locking or recurrent effusion, and negative McMurray test [11, 27, 28]. Functional outcomes were evaluated using the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) subjective knee score [29] and Lysholm knee score [30].

Hardware removal after the ACL reconstruction and meniscal repair was recommended to patients 1 year after the surgery. For patients who consented to hardware removal, the second-look arthroscopy was implemented at the time of hardware removal. On the second-look arthroscopy, the healing status of the repaired meniscus was evaluated by probing the repair site. Criteria established by Scott et al. [31] were used to evaluate the healing status. Healing status was graded as follows: complete healing, when the residual cleft at the repair site was < 10% of the thickness of the meniscus; incomplete healing, when the residual cleft residual cleft was < 50%; failure, when the residual cleft was > 50%. These criteria have been used for the assessment of meniscal healing in many previous studies [11, 28].

Statistics

SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. Between-group differences regarding continuous and categorical variables were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Fisher’s exact test, respectively. p values < 0.05 were considered indicative of statistically significant difference. A priori power analysis was conducted to determine the sample size (alpha level = 0.05 and power = 0.8). Pilot study was implemented using 20 knees in each group. Complete healing rate in suture and device groups was 85% and 50%, respectively. Assuming a statistical power of 0.80, the minimum sample size in each group was determined to be 27. In this study, 28 patients were included in the suture group and 33 patients were included in the device group.

Results

Table 2 summarizes the healing status of the repaired menisci in each group as evaluated by the second-look arthroscopy. In the cases included in this study, all tears were vertical. None of the patients included in this study had a history of trauma between the meniscal repair and the second-look arthroscopy.

No significant between-group difference was observed regarding the healing status of the repaired menisci in the red–red zone and red–white zone (red–red zone, p = 0.692; red–white zone, p = 0.293). However, the overall healing status in the suture group was significantly better than that in the device group (p = 0.048). In the suture group, 23 patients showed complete healing (82.1%), 4 patients showed incomplete healing (14.3%), and 1 patient showed failure (3.6%). In the device group, 18 patients showed complete healing (54.5%), 4 patients showed incomplete healing (24.2%), and 7 patients showed failure (21.2%).

Clinical success rate of meniscal repair in the suture and device groups was 89.3% (25 patients) and 81.8% (27 patients), respectively. There was no significant between-group difference in this respect (p = 0.488, Table 3). On comparison of functional outcomes at the last follow-up, suture group showed IKDC subjective knee scores of 85.2 ± 6.9 and Lysholm knee score of 85.4 ± 7.3; the corresponding scores in the device group were 84.2 ± 6.4 and 84.1 ± 7.1, respectively. No significant between-group difference was observed in this respect (p > 0.05, both parameters; Fig. 4a and b). No additional procedure was implemented in patients who were classified as ‘incomplete healing’ on second-look arthroscopy. Among the eight patients that were classified as ‘failure’, four patients either showed no symptoms or had stable tear site; hence, no additional procedure was implemented. Meniscectomy was performed in the remaining four patients.

Discussion

The principle finding of this study was that the all-inside repair technique using sutures showed a better healing rate than that achieved with the all-inside repair technique using meniscal fixation devices, as evaluated by second-look arthroscopy of patients who received ACL reconstruction and meniscal repair. However, no significant between-group difference was observed regarding the clinical success rate or functional outcomes.

There is an increasing consensus on the need for repair of traumatic meniscal tear in young and active patients. In particular, meniscal repair with concomitant ACL reconstruction has been shown to achieve a better healing rate and clinical outcomes as compared to that achieved with meniscal repair alone without ACL reconstruction [10, 32,33,34]. Hence, meniscal repair should be more actively considered in patients who have meniscal tear with concomitant ACL tear. There are several techniques for surgical repair of meniscal tears. The choice of technique is largely guided by the location of meniscal tear, the tear pattern, and the surgeon’s preference [10]. This study focused on the all-inside repair technique for posterior horn tears.

Several studies have reported the clinical outcomes of all-inside repair technique using sutures or meniscal fixation devices. In a study by Ahn et al. [11], 32 (82.1%) out of 39 patients that underwent meniscal repair using sutures and concurrent ACL reconstruction showed complete healing on second-look arthroscopy; the clinical success rate was 97.4% (38 out of 39 patients). Clinical success rates of > 80% result have been reported with meniscal repair using meniscal fixation devices [17,18,19, 25]. However, a few studies have compared the clinical outcomes of the two techniques using an objective method, such as MRI or second-look arthroscopy. Choi et al. [15] evaluated the healing status of repaired menisci of patients who received ACL reconstruction and meniscal repair using 1.5 T MRI; they compared the outcomes between 35 patients who received meniscal repair using sutures (suture group) and 25 patients who received meniscal repair using FasT-Fix (FasT-Fix group). Although they did not specifically report the timing of follow-up MRI, 26 menisci (74.3%) were healed, 3 menisci (8.6%) were partially healed, and 6 menisci (17.1%) were not healed in the suture group; in comparison, 15 menisci (64%) were healed, 7 menisci (24%) were partially healed, and 3 menisci (12%) were not healed in the FasT-Fix group. The between-group difference regarding the healing status was not statistically significant. Even though MRI is regarded as a useful tool for evaluation of meniscal injury, its reliability for evaluation of the healing status of the repaired meniscus is not so high. Miao et al. [35] used MRI to evaluate the post-meniscal repair healing status of patients with completely healed menisci that were confirmed by second-look arthroscopy; the diagnostic accuracy of MRI was found to be < 70%. Although MRI is an objective tool for evaluation of the condition of meniscus, second-look arthroscopy allows for a meaningful evaluation of the healing status of meniscus repaired using the all-inside repair technique with sutures or meniscal fixation devices.

In this study, healing rate on second-look arthroscopy in the suture group was better than those in the device group, which contradicts the findings of Choi et al. [15] As reported by previous studies, the better biomechanical stability conferred by vertical sutures is the likely reason for the better healing rate in the suture group. Although meniscal repair with use of meniscal fixation devices is technically less challenging, placement of vertical suture against the full thickness of meniscus while ensuring proper approximation at the tear site is difficult with this method. Imposing too little or too tight tension on the pre-tied self-sliding knot may have affected the healing negatively. Although there was no significant difference, more cases of tear in the red–red zone in suture group could have affected the healing rate.

Interestingly, no significant between-group difference was observed regarding clinical success rate and functional outcomes despite the significant between-group difference regarding the healing status as assessed on second-look arthroscopy; this could be related to the stability of the meniscal tear site. Although residual cleft measuring 10% or > 50% of meniscus thickness was left at the repair site of patients classified as ‘incomplete healing’ or ‘failure’, the unstable tear site may have become stable owing to partial healing. Consequently, these patients may not have exhibited symptoms that can be detected by clinical assessment. In this study, the duration of follow-up was relatively short and problems may develop at the partially healed or unhealed repair site in the medium or long term; therefore, assessment of clinical success rate and functional outcomes over a longer period is a key imperative.

This study has the following limitations. First, this was a retrospective study with a small number of patients. Second, the device group showed more red–white zone meniscal tears as compared to that in the suture group, although there was no statistically significant difference. Furthermore, the choice of the repair technique was not randomly determined, and not every patient received a review of their arthroscopic findings. Hence, the impact of selection bias should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. Additionally, in this study, a subgroup analysis according to the orientation of the suture was not conducted. However, no patients in this study received only horizontal or oblique sutures at the entire tear site. Fourth, for the purpose of evaluation of healing status, no distinction was made between lateral and medial meniscal tears. Fifth, second-look arthroscopy does not allow for assessment of intra-meniscal tear. Hence, healing status of the repaired meniscus based on second-look arthroscopy can differ from the healing status as evaluated by MRI.

Conclusions

Among patients who received meniscal repair with concomitant ACL reconstruction, suture group showed a better healing status of the repaired meniscus based on second-look arthroscopy than the device group. However, no significant difference was observed regarding clinical success rate and functional outcomes.

References

Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA (2012) The basic science of human knee menisci: structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 4(4):340–351

Makris EA, Hadidi P, Athanasiou KA (2011) The knee meniscus: structure-function, pathophysiology, current repair techniques, and prospects for regeneration. Biomaterials 32(30):7411–7431

Syam K, Chouhan DK, Dhillon MS (2017) Outcome of ACL reconstruction for chronic ACL Injury in knees without the posterior horn of the medial meniscus: comparison with ACL reconstructed knees with an intact medial meniscus. Knee Surg Relat Res 29(1):39–44

Lee DY, Park YJ, Kim HJ, Nam DC, Park JS, Song SY, Kang DG (2018) Arthroscopic meniscal surgery versus conservative management in patients aged 40 years and older: a meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 138(12):1731–1739

Levy AS, Meier SW (2003) Approach to cartilage injury in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Orthop Clin North Am 34(1):149–167

Smith JP 3rd, Barrett GR (2001) Medial and lateral meniscal tear patterns in anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knees. A prospective analysis of 575 tears. Am J Sports Med 29(4):415–419

Tandogan RN, Taser O, Kayaalp A, Taskiran E, Pinar H, Alparslan B, Alturfan A (2004) Analysis of meniscal and chondral lesions accompanying anterior cruciate ligament tears: relationship with age, time from injury, and level of sport. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 12(4):262–270

Fetzer GB, Spindler KP, Amendola A, Andrish JT, Bergfeld JA, Dunn WR, Flanigan DC, Jones M, Kaeding CC, Marx RG, Matava MJ, McCarty EC, Parker RD, Wolcott M, Vidal A, Wolf BR, Wright RW (2009) Potential market for new meniscus repair strategies: evaluation of the MOON cohort. J Knee Surg 22(3):180–186

Mehl J, Otto A, Baldino JB, Achtnich A, Akoto R, Imhoff AB, Scheffler S, Petersen W (2019) The ACL-deficient knee and the prevalence of meniscus and cartilage lesions: a systematic review and meta-analysis (CRD42017076897). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 139(6):819–841

Hutchinson ID, Moran CJ, Potter HG, Warren RF, Rodeo SA (2014) Restoration of the meniscus: form and function. Am J Sports Med 42(4):987–998

Ahn JH, Wang JH, Yoo JC (2004) Arthroscopic all-inside suture repair of medial meniscus lesion in anterior cruciate ligament–deficient knees: results of second-look arthroscopies in 39 cases. Arthroscopy 20(9):936–945

Barrett GR, Richardson K, Ruff CG, Jones A (1997) The effect of suture type on meniscus repair. A clinical analysis. Am J Knee Surg 10(1):2–9

Ahn JH, Kim SH, Yoo JC, Wang JH (2004) All-inside suture technique using two posteromedial portals in a medial meniscus posterior horn tear. Arthroscopy 20(1):101–108

Albrecht-Olsen P, Kristensen G, Burgaard P, Joergensen U, Toerholm C (1999) The arrow versus horizontal suture in arthroscopic meniscus repair. A prospective randomized study with arthroscopic evaluation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 7(5):268–273

Choi NH, Kim BY, Hwang Bo BH, Victoroff BN (2014) Suture versus FasT-Fix all-inside meniscus repair at time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 30(10):1280–1286

Kotsovolos ES, Hantes ME, Mastrokalos DS, Lorbach O, Paessler HH (2006) Results of all-inside meniscal repair with the FasT-Fix meniscal repair system. Arthroscopy 22(1):3–9

Haas AL, Schepsis AA, Hornstein J, Edgar CM (2005) Meniscal repair using the FasT-Fix all-inside meniscal repair device. Arthroscopy 21(2):167–175

Kalliakmanis A, Zourntos S, Bousgas D, Nikolaou P (2008) Comparison of arthroscopic meniscal repair results using 3 different meniscal repair devices in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction patients. Arthroscopy 24(7):810–816

Popescu D, Sastre S, Caballero M, Lee JW, Claret I, Nunez M, Lozano L (2010) Meniscal repair using the FasT-Fix device in patients with chronic meniscal lesions. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18(4):546–550

Choi NH, Kim TH, Victoroff BN (2009) Comparison of arthroscopic medial meniscal suture repair techniques: inside-out versus all-inside repair. Am J Sports Med 37(11):2144–2150

Kang DG, Park YJ, Yu JH, Oh JB, Lee DY (2018) A systematic review and meta-analysis of arthroscopic meniscus repair in young patients: comparison of all-inside and inside-out suture techniques. Knee Surg Relat Res 31(1):1

Terai S, Hashimoto Y, Yamasaki S, Takahashi S, Shimada N, Nakamura H (2019) Prevalence, development, and factors associated with cyst formation after meniscal repair with the all-inside suture device. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 139(9):1261–1268

Kang DG, Park YJ, Yu JH, Oh JB, Lee DY (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of arthroscopic meniscus repair in young patients: comparison of all-inside and inside-out suture techniques. Knee Surg Relat Res 31(1):1–11

Buckland DM, Sadoghi P, Wimmer MD, Vavken P, Pagenstert GI, Valderrabano V, Rosso C (2015) Meta-analysis on biomechanical properties of meniscus repairs: are devices better than sutures? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23(1):83–89

Farng E, Sherman O (2004) Meniscal repair devices: a clinical and biomechanical literature review. Arthroscopy 20(3):273–286

Mutsaerts EL, van Eck CF, van de Graaf VA, Doornberg JN, van den Bekerom MP (2016) Surgical interventions for meniscal tears: a closer look at the evidence. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 136(3):361–370

Barrett GR, Field MH, Treacy SH, Ruff CG (1998) Clinical results of meniscus repair in patients 40 years and older. Arthroscopy 14(8):824–829

Kang HJ, Chun CH, Kim KM, Cho HH, Espinosa JC (2015) The results of all-inside meniscus repair using the viper repair system simultaneously with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Surg 7(2):177–184

Irrgang JJ, Anderson AF, Boland AL, Harner CD, Kurosaka M, Neyret P, Richmond JC, Shelborne KD (2001) Development and validation of the international knee documentation committee subjective knee form. Am J Sports Med 29(5):600–613

Lysholm J, Gillquist J (1982) Evaluation of knee ligament surgery results with special emphasis on use of a scoring scale. Am J Sports Med 10(3):150–154

Scott GA, Jolly BL, Henning CE (1986) Combined posterior incision and arthroscopic intra-articular repair of the meniscus. An examination of factors affecting healing. J Bone Joint Surg Am 68(6):847–861

Kimura M, Shirakura K, Hasegawa A, Kobuna Y, Niijima M (1995) Second look arthroscopy after meniscal repair. Factors affecting the healing rate. Clin Orthop Relat Res 314:185–191

Morgan CD, Wojtys EM, Casscells CD, Casscells SW (1991) Arthroscopic meniscal repair evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Am J Sports Med 19(6):632–637 (discussion 637–638)

Paxton ES, Stock MV, Brophy RH (2011) Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: a systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy 27(9):1275–1288

Miao Y, Yu JK, Zheng ZZ, Yu CL, Ao YF, Gong X, Wang YJ, Jiang D (2009) MRI signal changes in completely healed meniscus confirmed by second-look arthroscopy after meniscal repair with bioabsorbable arrows. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 17(6):622–630

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Formal consent was not required for the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This work was performed at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Inje University Busan Paik Hospital, Busan, Republic of Korea.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seo, SS., Kim, CW., Lee, CR. et al. Second-look arthroscopic findings and clinical outcomes of meniscal repair with concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: comparison of suture and meniscus fixation device. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 140, 365–372 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-019-03323-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00402-019-03323-3