Abstract

Purpose

To assess the relationship between dietary oily fish intake and all-cause mortality in a population of frequent fish consumers of Amerindian ancestry living in rural Ecuador.

Methods

Individuals aged ≥ 40 years enrolled in the prospective population-based Atahualpa Project cohort received annual questionnaires to estimate their dietary oily fish intake. Only fish served broiled or cooked in the soup were included for analysis. Poisson regression and Cox-proportional hazards models adjusted for demographics, education level and cardiovascular risk factors were obtained to estimate mortality risk according to the amount of oily fish intake stratified in tertiles.

Results

Analysis included 909 individuals (mean age: 55.1 ± 12.8 years) followed by a median of 7.5 ± 3 years. Mean oily fish intake was 9.4 ± 5.7 servings per week. A total of 142 (16%) individuals died during the follow-up. The mortality rate for individuals in the first tertile de oily fish intake (0.0–6.29 servings) was 2.87 per 100 person-years, which decreased to 1.78 for those in the third tertile (10.59–35.0 servings). An adjusted Cox-proportional hazards model showed that individuals allocated to the second (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.41–0.92) and third (HR 0.60; 95% CI 0.40–0.91) tertiles of dietary oily fish intake had significantly lower mortality risk than those in the first tertile.

Conclusion

Sustained oily fish intake of more than six servings per week reduces mortality risk in middle-aged and older adults of Amerindian ancestry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Several beneficial effects have been attributed to dietary oily fish intake, particularly in reducing the risk of adverse cardiovascular and neurological outcomes [1,2,3,4]. While these effects are largely mediated by anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, antiarrhythmic, antihypertensive and antithrombotic properties of marine long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-3 PUFAs) [5,6,7], additional nutrients present in oily fish—proteins, vitamin D, selenium—may also contribute to these favorable outcomes [8]. Such findings are not universal as some studies have shown no effect of oily fish on the investigated outcomes [9, 10]. These discrepancies can most likely be attributed to differences in study designs, to a narrow range of fish intake in the studied population and, perhaps of even greater importance, to differences in ethnicity among the investigated populations.

Following the preliminary report of Bang et al. [11], evidence has accumulated supporting the concept that certain ethnic groups—especially the Inuit and their Amerindian descendants—may be particularly favored by the effects of a diet rich in oily fish [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Beneficial effects appear to be linked to genetic signatures of natural selection that make certain ethnic groups physiologically adapted to a diet rich in ω-3 PUFAs [18]. These genetic variations may exert a profound influence on cardiometabolic phenotypes, making affected individuals less susceptible to developing diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease and possibly conditions such as cancer or neurological disorders.

Some studies have attempted to demonstrate an inverse relationship between dietary oily fish intake and mortality risk, but their results have been inconsistent [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Some studies based on European populations failed to confirm an inverse relationship [19, 20]. Another cosmopolitan study found an oily fish intake-related reduction in mortality only among individuals with previous vascular disease but not in the general population [21]. Other studies based on Inuit populations (Alaska and Northern Canada) have suggested that dietary oily fish intake may be a protective factor against mortality [22,23,24].

To the best of our knowledge, no study has assessed mortality risk according to the amount of dietary oily fish intake in native Latin American populations that potentially share the genetic signatures found in the Inuit and their descendants. Seizing on the Atahualpa Project cohort, this longitudinal prospective study aims to assess the relationship between oily fish intake and all-cause mortality in a population of frequent fish consumers of Amerindian ancestry.

Material and methods

Study population

Atahualpa is a rural village of about 3500 inhabitants located in coastal Ecuador, 10 miles west of the Pacific Ocean (2º18′S, 80º46′W). The weather is warm and dry, with 12 daily hours of sunlight all year long. As detailed elsewhere, Atahualpa residents are homogeneous in regard to ethnicity, levels of education, socio-economic status, and dietary habits [25]. Most men work as artisan carpenters or farmers and most women are homemakers. The diet is ancestrally rich in oily fish, vegetables and carbohydrates but poor in dairy products and other types of meat. Consumption of other foods rich in ω-3 PUFAs, as well as the use of fish oils supplements, is almost nonexistent in the village. People get food from the local market and small grocery stores where highly processed foods are exceptionally found. There are no restaurants in the village and most people have meals at home.

Phenotypic characteristics of the population suggest their Amerindian ancestry. This is a vast population of about 70 million people living in different countries that already inhabit The Americas before the Spaniards came to our Continent. It has been estimated that they are about 13,000 years old, and theories support the fact that they are descendants of people living in Beringia that moved down after the last age of ice. They have a particular phenotype and a unique genotype. Phenotypic characteristics include olive-moderate brown skin (Type IV in the Fitzpatrick scale), dark brown eyes and hair, short stature, and a predominantly elliptic hard palate [26]. In addition, a genome-wide analysis conducted in a representative sample of individuals enrolled in the present study demonstrated that these people have a large proportion of Amerindian ancestry (94.1%), which is higher than that found in other native populations of Ecuador and some neighboring countries (Brandt DYC, Del Brutto OH and Nielsen R, unpublished results). This analysis also revealed signatures of natural selection in genes involved in fat metabolism that could play a role in the beneficial effect of ω-3 PUFAs on several outcomes previously investigated in this cohort [13,14,15,16].

Study design

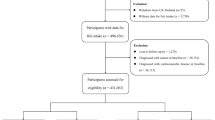

Atahualpa residents aged ≥ 40 years, identified by means of annual door-to-door surveys (June 2012–June 2019), were enrolled in the Atahualpa Project cohort after they signed a comprehensive informed consent. Demographics, level of education, and cardiovascular risk factors were determined at baseline. The first questionnaire for assessing dietary oily fish intake was applied within the first year after enrollment for those entering the cohort in 2012 and at the time of enrollment for those entering from 2013 to 2019. Following a longitudinal prospective study design, individuals were screened yearly to repeat the fish intake questionnaire and to inquiry participants’ proxies about changes in vital status in individuals who were already enrolled but were not present during the new survey. Those who emigrated or declined consent were taken out of the cohort at the administrative censoring date of the last annual survey when the individual was interviewed. Persons who died were censored on the day of death, which was confirmed by reviewing death certificates. For the current analysis, the last censoring date was set as June 2022. The study followed the STROBE checklist (The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [27].

Assessment of dietary oily fish intake

Before the study, we visited the local market to make a list of the fishes most commonly bought by Atahualpa residents. We also weighed the edible parts of each of the species of fish to make an accurate estimation of the number of servings per week ingested by each individual (each serving equals 140 g). While the availability of any particular type of fish varies from week to week, Pacific Moonfish (Selene peruviana), Pacific Bumperfish (Chloroscombrus orqueta), Pacific Mackerel (Scomber japonicus), Shortjaw Leatherjacket (Oligoplites refulgens), Pacific Thread Herring (Opisthonema libertate) and Sardine (Sardine pilcardus) are the species most frequently eaten by Atahualpa residents. These fishes are wild-caught close to the Pacific border and, with the exception of Pacific Moonfish which is a lean fish, are among the fish species with the highest content of marine ω-3 PUFAs (1.3–2.5 g per serving) [8]. In addition, due to their relatively small size (15–50 cm) their methyl-mercury content is low [28].

At each survey, study participants were asked to quantify their regular weekly consumption of the various types of oily fish, and we used the mean of these values in our analysis. Only fishes served broiled or cooked in the soup were included; fried oily fish and lean fish were excluded for analysis.

Covariates investigated

Demographics (age and sex), level of education (up to primary school or higher), and traditional cardiovascular risk factors were assessed at baseline and selected as potential confounders. Assessment of cardiovascular risk factors followed the Life’s Simple 7 scale, an initiative of the American Heart Association aimed to define the cardiovascular health status of individuals [29]. This scale has been used in people from diverse races/ethnic groups living in both urban and rural settings and has demonstrated an inverse relationship with mortality irrespective of differences across regional disparities in cardiovascular risk factors [30,31,32]. The Life’s Simple 7 scale is composed of four health behaviors and three health factors, which were categorized in the ideal range according to well-defined parameters, as follows: (1) smoking status: never or quit > 1 year; (2) body mass index: < 25 kg/m2; (3) physical activity: ≥ 150 min/week of moderate intensity or ≥ 75 min/week of vigorous intensity or equivalent combination; (4) healthy diet: 4–5 components based on five components detailed by the American Heart Association [29]; (5) blood pressure: untreated and < 120/ < 80 mmHg; (6) fasting glucose: untreated and < 100 mg/dL; and (7) total cholesterol blood levels: untreated and < 200 mg/dL.

Of interest, diet was not included as a covariate in this study to avoid collinearity (since fish intake is a component of a healthy diet). In addition, the use of medications was not taken into account as a reliable covariate since less than 15% of the study population with vascular risk factors received proper therapy during the study years.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were carried out by using STATA version 17 (College Station, TX, USA). Univariate comparisons for mortality rates according to tertiles of dietary oily fish intake used the log-rank test. To compute the person-years of follow-up we considered the time from enrollment to the last censoring date, study drop-out, or the day of death. Using Poisson regression models, we calculated the mortality incidence rate ratio (IRR) according to the servings of dietary oily fish intake per week (stratified in tertiles). Cox-proportional hazards models adjusted for demographics, level of education, and cardiovascular risk factors were fitted to calculate the hazard ratio (HR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) to estimate the risk for all-cause mortality according to the amount of dietary oily fish intake stratified in tertiles.

Results

Of 933 Atahualpa residents aged ≥ 40 years enrolled in the Atahualpa Project cohort (2012–2019), 909 (97%) received interviews for dietary oily fish intake and were included in this cohort. The remaining 24 individuals either died (n = 9) between enrollment and the invitation to participate in this study or declined consent (n = 15). There were no significant differences in clinical characteristics across individuals who participated in this study and those who did not. The total follow-up in the population was 6776 person-years and the median follow-up was 7.5 ± 3 years. Individuals censored before the end of the study were those who emigrated (n = 47), declined further consent (n = 55), or died (n = 142) during the study years; however, they also counted toward the total time of follow-up.

For a total of 6,776 person-years of follow-up, we needed at least 101 deaths to get a hazard ratio of 0.57 at the alpha level of 0.05 and with 80% power. Therefore, our sample had enough statistical power to detect differences in the relationship between dietary oily fish intake and all-cause mortality.

The mean (± SD) age of study participants at enrollment was 55.1 ± 12.8 years (median age: 53 years), 491 (54%) were women, and 514 (57%) had primary school education only. Cardiovascular health metrics in the ideal range were as follows: smoking status: 867 (95%); body mass index: 301 (33%); physical activity: 426 (47%); blood pressure: 319 (35%); fasting glucose: 322 (35%); and total cholesterol blood levels: 557 (61%). Mean dietary intake of oily fish was 9.4 ± 5.7 servings per week (range 0–35), with 315 individuals allocated to the first tertile (0–6.29 servings), 291 to the second tertile (6.30–10.58 servings), and the remaining 303 to the third tertile (10.59–35 servings).

In unadjusted analysis, individuals who died during the study years were older at baseline and were less educated than those who survived. Several cardiovascular health metrics in the ideal range (physical activity, blood pressure, fasting glucose, and total cholesterol blood levels) were less frequent among subjects who died during the study; in contrast, survivors had less often a body mass index in the ideal range than those who died (Table 1).

Also in unadjusted analysis, we found differences in mortality across tertiles of dietary oily fish intake by the use of the log-rank test, which takes into account person-years of follow-up (Table 2).

Using a Poisson regression model (adjusted for all the above-mentioned covariates), the mortality rate for individuals in the first tertile de oily fish intake was 2.87 per 100 person-years (95% CI 2.20–3.55), which decreased to 1.78 (95% CI 1.18–2.37) for those in the third tertile. There was no difference between the second and the third tertile.

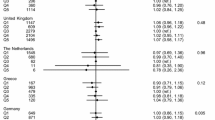

An adjusted Cox-proportional hazards model showed that individuals allocated to the second and third tertiles of dietary oily fish intake had significantly lower mortality risk than those in the first tertile (Fig. 1). In this model, increased age at baseline was directly associated with all-cause mortality while being female, and having physical activity, blood pressure and total cholesterol blood levels in the ideal range were inversely associated with the outcome (Table 3).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves and hazards ratios with 95% confidence intervals for all-cause mortality according to dietary oily fish intake stratified in tertiles, adjusted for demographics, level of education and cardiovascular risk factors. There is a significant difference in mortality across individuals allocated to the first tertile compared to those in the second and third tertile

Discussion

In this population-based cohort of community-dwellers of Amerindian ancestry living in a rural Ecuadorian village, dietary oily fish intake is inversely associated with all-cause mortality, independently of demographics, level of education and cardiovascular risk factors included in the Life’s simple 7 constructs. Mortality is higher for individuals allocated to the first tertile of oily fish intake compared to those in the second and third tertiles, suggesting that a regular intake of more than six servings per week is needed to achieve the beneficial outcome. Also of interest, the analysis shows that more than 10 servings per week do not seem to further reduce mortality risk but neither does it increase mortality. This suggests that potential toxins, such as methyl-mercury, that may be found in fish ingested by this population do not make a significant contribution to all-cause mortality.

Our explanation for the results of the present study may be found in the genetic background of the population. It has been established that the traditional food source of the Inuit contains high levels of marine ω-3 PUFAs [33]. They have developed distinctive genetic adaptations that counteract the deleterious effects of fatty acids through a mechanism mediated by desaturases enzymes. It has been proven that these mutations decrease levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and fasting insulin, thus exerting a protective effect against cardiovascular diseases and diabetes [18]. As has been recently demonstrated, some signatures of natural selection persist in Native Americans descendent from the Inuit (Brandt DYC, Del Brutto OH and Nielsen R, unpublished results). These hereditary mutations may have helped these Native American populations adapt to a high-fat and high-protein diet [34], and should be considered when evaluating the outcomes of studies of dietary oily fish intake and its associated mortality risk.

Results of the present study differ from those reported in other ethnic groups. For example, a large retrospective study combining results from almost 200,000 individuals included in one population-based study and three intervention trials failed to document a significant reduction in mortality according to the amount of oily fish intake in subjects with no known vascular disease, and only revealed a modest reduction in mortality among individuals with established vascular disease [21]. Despite the recruitment of people from 58 countries, individuals of Amerindian ancestry were either not included or not analyzed separately from the rest of the cohort. Also, the stratification of dietary oily fish intake compared individuals with less than 50 g per month versus those who consume 175 or 350 g per week. According to the results of our study in individuals of Amerindian ancestry that level of consumption might be insufficient to achieve the desired effect. In this population, the amount of oily fish needed to achieve its beneficial effects appears to differ for each of the attributed benefits. According to previous studies from our group, up to five servings per week reduced arterial blood pressure levels [13], more than four servings per week were associated with better cognitive performance [14], ten additional servings per week were needed to improve sleep quality by 9.3% [15], and more than three servings per week improved arterial stiffness [16]. Generalization of these findings to other races/ethnic groups should be undertaken with caution until more information is available.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths including its population-based longitudinal prospective design, the homogeneity of the study population regarding ethnic background and lifestyle, and the systematic assessment of cardiovascular risk factors and dietary oily fish intake by means of standardized protocols that have previously been validated in the same population [13, 32]. Another important strength is the lack of bias because all study participants were of the same socio-economic strata and did not consume fish in pursuit of a healthy diet, as occurs with individuals living in urban centers of high-income countries [35]. Instead, in this underserved rural population, their diet is mostly based on oily fish because that is the most affordable source of animal protein.

Nevertheless, the study has limitations. We relied on the self-reported number of oily fish servings per week rather than measuring ω-3 PUFAs concentrations in the blood or adipose tissue; at the same time, the aim of the study was to assess the impact of oily fish consumption on all-cause mortality and not the specific role of ω-3 PUFAs. Precise ascertainment of the actual causes of death was not possible because of suspected inaccuracies in the death certificates. It is also possible that some unmeasured confounders may have accounted for at least part of the findings. Less than 15% of the population with vascular risk factors were adequately treated during the study years despite our encouragement on medication compliance. This precluded assessment of the influence of medications on the relationship between dietary oily fish intake and mortality. Alternatively, this could be considered a strength of the study since we had the unique opportunity to observe the effects of oily fish intake in a mostly untreated population. Given that the study population was limited to individuals of Amerindian ancestry, the results may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups, but this limitation is consistent with the aims of the study.

Conclusions

Results of this study suggest that sustained dietary oily fish intake at doses of more than six servings per week reduces mortality risk in middle-aged and older adults of Amerindian ancestry. Further studies in populations with the similar genetic background are needed to confirm our findings and to gain insight into the physiological mechanisms that underlie the beneficial effect of oily fish.

Data availability

Aggregated data from this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Panagiotakos DB, Zeimbekis A, Boutziouka V, Economou M, Kourlaba G, Toutouzas P (2007) Long-term fish intake is associated with better lipid profile, arterial blood pressure, and blood glucose levels in elderly people from Mediterranean islands (MEDIS epidemiological study). Med Sci Monit 13(7):CR307-312

Zhang J, Wang C, Li L, Man Q, Meng L, Song P, Froyland L, Du ZY (2012) Dietary inclusion of salmon, herring and pompano as oily fish resources reduces CVD risk markers in dyslipidaemic middle-aged and elderly Chinese women. Br J Nutr 108(8):1455–1465. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114511006866

Gammelmark A, Nielsen MS, Bork CS, Lundbye-Christensen S, Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Schmidt EG (2016) Association of fish consumption and dietary intake of n-3 PUFA with myocardial infarction in a prospective Danish study. Br J Nutr 116(1):167–177. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451600180X

Nozaki S, Sawada N, Matsuoka YJ, Shikimoto R, Mimura M, Tsugane S (2021) Association between dietary fish and PUFA intake in midlife and dementia in later life: the JPHC Saku Mental Health Study. J Alzheimer Dis 79(3):1091–1104. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-191313

van Bussel BCT, Henry RMA, Schalkwijk CG, Ferreira I, Feskens EJM, Streppel MT, Smulders YM, Twisk JWR, Stehouwer CDA (2011) Fish consumption in health adults is associated with decreased circulating biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction and inflammation during a 6-year follow-up. J Nutr 141(9):1719–1725. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.111.139733

Tousoulis D, Plastiras A, Siasos G, Oikonomou E, Verveniotis A, Kokkou K, Maniatis K, Gouliopoulos N, Miliou A, Paraskevopoulos T, Stefanadis C (2014) Omega-3 PUFAs improved endothelial function and arterial stiffness with a parallel antiinflamatory effect in adults with metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis 232(1):10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.10.014

Mori TA (2014) Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology and effects on cardiometabolic risk factors. Food Funct 5(9):2004–2019. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4fo00393d

Weichselbaum E, Com S, Buttriss J, Spanner S (2013) Fish in the diet: a review. Nutrition Bull 38(2):128–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/nbu.12021

Ness AR, Whitley E, Burr ML, Elwood PC, Smith GD, Ebrahim S (1999) The long-term effect of advice to eat more fish on blood pressure in men with coronary disease: results from the diet and reinfarction trial. J Hum Hypertens 13(11):729–733. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jhh.1000913

Rhee JJ, Kim E, Buring JE, Kurth T (2017) Fish consumption, omega-3 fatty acids, and risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Prev Med 52(1):10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.07.020

Bang HO, Dyerberg J, Nielsen AB (1971) Plasma lipid and lipoprotein pattern in Greenlandic west-coast Eskimos. Lancet 1(7719):1143–1145. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(71)91658-8

Fodor JG, Helis E, Yazdekhasti N, Vohnout B (2014) “Fishing” for the origins of the “Eskimo and heart disease” story: facts or wishful thinking? Can J Cardiol 30(8):864–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2014.04.007

Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Gillman J, Castillo PR, Zambrano M, Ha J-E (2016) Dietary oily fish intake and blood pressure levels: a population-based study. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 18(4):337–341. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12684

Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Gillman J, Zambrano M, Ha J-E (2016) Oily fish intake and cognitive performance in community-dwelling older adults: the Atahualpa Project. J Community Health 41(1):82–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-015-0070-9

Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Ha JE, Gillman J, Zambrano M, Castillo PR (2016) Dietary fish intake and sleep quality: a population-based study. Sleep Med 17:126–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2015.09.021

Del Brutto OH, Recalde BY, Mera RM (2021) Dietary oily fish intake is inversely associated with severity of white matter hyperintensities of presumed vascular origin. A population-based study in frequent fish consumers of Amerindian ancestry. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 30(6):105778. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105778

Senftleber NK, Albrechtsen A, Lauritzen L, Larsen CL, Bjerregaard P, Diaz LJ, Ronn PF, Jorgensen ME (2020) Omega-3 fatty acids and risk of cardiovascular disease in Inuit: first prospective cohort study. Atherosclerosis 312:28–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2020.08.032

Fumagalli M, Moltke I, Grarup N, Racimo F, Bjerregaard P, Jorgensen ME et al (2015) Greenlandic Inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation. Science 349(6254):1343–1347. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2319

de Goede J, Geleijnse JM, Boer JM, Kromhout D, Verschuren WM (2010) Marine (n-3) fatty acids, fish consumption, and the 10-year risk of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease in a large population of Dutch adults with low fish intake. J Nutr 140(5):1023–1028. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.119271

Engeset D, Braaten T, Teucher B, Kuhn T, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Leenders M et al (2015) Fish consumption and mortality in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort. Eur J Epidemiol 30(1):57–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-014-9966-4

Mohan D, Mente A, Dehghan M, Rangarajan S, O’Donell M, Hu W et al (2021) Associations of fish consumption with risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality among individuals with or without vascular disease from 58 countries. JAMA Intern Med 181(5):631–649. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0036

Dewailly E, Blanchet C, Lemieux S, Sauvé L, Gingras S, Ayotte P, Holub BP (2001) n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease risk factors among the Inuit of Nunavik. Am J Clin Nutr 74(4):464–473. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/74.4.464

Dewailly E, Blanchet C, Gingras S, Lemieux S, Holub BJ (2002) Cardiovascular disease risk factors and n-3 fatty acid status in the adult population of James Bay Cree. Am J Clin Nutr 76(1):85–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.1.85

McLaughlin J, Middaugh J, Boudreau D, Malcom G, Parry S, Tracy R, Newman W (2005) Adipose tissue triglyceride fatty acids and atherosclerosis in Alaska natives and non/natives. Atherosclerosis 181(2):353–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.01.019

Del Brutto OH, Peñaherrera E, Ochoa E, Santamaría M, Zambrano M, Del Brutto VJ, Atahualpa Project Investigators (2014) Door-to-door survey of cardiovascular health, stroke, and ischemic heart disease in rural coastal Ecuador – the Atahualpa Project: methodology and operational definitions. Int J Stroke 9(3):367–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12030

Castillo PR, Mera RM, Zambrano M, Del Brutto OH (2014) Population-based study of facial morphology and excessive daytime somnolence. Pathophysiology 21(4):289–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pathophys.2014.06.001

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, Initiative STROBE (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370(9596):1453–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X

Tollefson L, Cordle L (1986) Methylmercury in fish: a review of residue levels, fish consumption and regulatory actions in the United States. Environ Health Perspect 68:203–208. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.8668203

Lloyd-Jones D, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L et al (2010) Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion. The American Heart Association’s strategic impact goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation 121(4):586–613. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703

Ahmad MI, Chevli PA, Barot H, Soliman EZ (2019) Interrelationships between American Heart Association’s life’s simple 7, ECG silent myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular mortality. J Am Heart Assoc 8(6):e011648. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.011648

Commodore-Mensah Y, Mok Y, Gottesman RF, Kucharska-Newton A, Matsushita K, Palta P, Rosamond WD, Sarfo FS, Coresh J, Koton S (2022) Life’s Simple 7 at midlife and risk of recurrent cardiovascular disease and mortality after stroke: the ARIC study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 31(7):106486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2022.106486

Del Brutto OH, Mera RM, Recalde BY, Rumbea DA, Sedler MJ (2021) Life’s simple 7 and all-cause mortality. A population-based prospective cohort study in middle-aged and older adults of Amerindian ancestry living in rural Ecuador. Prev Med Rep 25:101668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101668

Bang HO, Dyerberg J, Sinclair HM (1980) The composition of the Eskimo food in north western Greenland. Am J Clin Nutr 33(12):2657–2661. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/33.12.2657

Amorin CEG, Nunes K, Meyer D, Comas D, Bortolini MC, Salzano FM, Hunemeier T (2017) Genetic signature of natural selection in first Americans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(9):2195–2199. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1620541114

Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, Drescher G, Ferro-Luzzi A, Helsing E, Trichopoulos D (1995) Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr 61(Suppl 6):1402S-1406S. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/61.6.1402S

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the field personnel of the Atahualpa Project Cohort for their valuable contribution to this study.

Funding

This study was partially supported by an unrestricted grant from Universidad Espiritu Santo-Ecuador, Samborondón, Ecuador.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OHD: study conceptualization and design; OHD and MJS: wrote the manuscript; RMM: conducted the statistical analysis; BYR: data collection and analysis; DAR: project administration, study coordinator. All authors contributed to the critical review and editing of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital-Clínica Kennedy, Guayaquil (FWA 00030727). All participants gave signed informed consent, including permission to use their data for research purposes.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Del Brutto, O.H., Mera, R.M., Recalde, B.Y. et al. Dietary oily fish intake reduces the risk of all-cause mortality in frequent fish consumers of Amerindian ancestry living in coastal Ecuador: the Atahualpa project. Eur J Nutr 62, 1527–1533 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03093-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-023-03093-0