Abstract

Purpose

Although evidence indicates that both physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet) reduce the risk of all-cause mortality, a little is known about optimal intensities of physical activity and their combined effect with MedDiet in older adults. We assessed the separate and combined associations of leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) and MedDiet adherence with all-cause mortality.

Methods

We prospectively studied 7356 older adults (67 ± 6.2 years) at high vascular risk from the PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea study. At baseline and yearly thereafter, adherence to the MedDiet and LTPA were measured using validated questionnaires.

Results

After 6.8 years of follow-up, we documented 498 deaths. Adherence to the MedDiet and total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA were inversely associated with all-cause mortality (p < 0.01 for all) in multiple adjusted Cox regression models. The adjusted hazard of all-cause mortality was 73% lower (hazard ratio 0.27, 95% confidence interval 0.19–0.38, p < 0.001) for the combined category of highest adherence to the MedDiet (3rd tertile) and highest total LTPA (3rd tertile) compared to lowest adherence to the MedDiet (1st tertile) and lowest total LTPA (1st tertile). Reductions in mortality risk did not meaningfully differ between total, light intensity, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA.

Conclusions

We found that higher levels of LTPA, regardless of intensity (total, light and moderate-to-vigorous), and greater adherence to the MedDiet were associated separately and jointly with lower all-cause mortality. The finding that light LTPA was inversely associated with mortality is relevant because this level of intensity is a feasible option for older adults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In an increasingly aged society [1], it is paramount to search for strategies that could contribute to improve health and increase lifespan in older individuals [2]. There is convincing evidence that consuming a healthy diet and engaging in physical activity are independently associated with lower rates of mortality in the general population [3,4,5,6]. Consequently, most recent dietary guidelines emphasize the importance of an active lifestyle, in addition to a healthy dietary pattern [7,8,9]. Most national guidelines recommend 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per week, which corresponds to an energy expenditure of 500 metabolic equivalent task (MET)-minutes per week [10]. However, even lower levels of MVPA significantly reduce premature mortality in older populations [3, 11]. Additionally, emerging evidence shows that light physical activity is inversely associated with all-cause mortality [12]. This is particularly important for older adults with reduced physical capabilities.

Higher adherence to a healthy diet has also been associated with lower rates of mortality in the general population [5, 6]. Recent findings in older adults suggest that higher adherence to a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet (MedDiet), was not only associated with numerous health benefits [13,14,15], but was also related to a 14–34% decrease in all-cause mortality [16,17,18]. An integrative approach including key lifestyle behaviours such as diet and physical activity in efforts to address the burden of chronic diseases leading to premature mortality may be more effective than focussing on a single lifestyle factor. However, there is little evidence on the joint impact of physical activity and adherence to the MedDiet on all-cause mortality [19].

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to analyse the separate and joint association of leisure-time physical activity (LTPA) and MedDiet adherence with all-cause mortality in older Spanish individuals at high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Additionally, we analysed the impact of different intensities of physical activity, separately and together with different levels of adherence to the MedDiet, on all-cause mortality.

Methods

The present study was a prospective cohort analysis within the framework of the PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea (PREDIMED) study. The complete protocol of the PREDIMED study was reported in detail elsewhere and in http://www.predimed.es [20,21,22]. In brief, this multicentre, randomized, controlled clinical trial assessed the effects of the MedDiet on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The intervention trial was carried out between 2003 and 2008, and it continues as an observational cohort study. Older individuals were selected from 11 recruitment centres in Spain, and then randomly allocated to one of three diet groups: MedDiet enriched with extra-virgin olive oil, MedDiet enriched with mixed nuts, and advice to follow a low-fat diet. The Institutional Review Board of all participating centres approved the study protocol and the trial was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study is registered at ISRCTN35739639 [23].

Study population

Eligible participants were 3165 men (aged 55–80 years) and 4282 women (60–80 years old) free of cardiovascular disease but at high cardiovascular risk at enrolment. Participants had either type 2 diabetes or at least three of the following cardiovascular risk factors: current smoking (> 1 cigarette a day in the last month), hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, or taking antihypertensive medication), low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (≤ 40 mg/dl in men or ≤ 50 mg/dl in women), elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (≥ 160 mg/dl or taking lipid-lowering medication), overweight/obesity (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), and family history of premature coronary heart disease. Exclusion criteria were the previous history of CVD, stroke or peripheral arterial disease, any severe chronic illness, immunodeficiency or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive status, illegal drug or alcohol misuse, history of allergy to olive oil or nuts and low predicted likelihood of changing dietary habits [21]. We finally included 7356 individuals (3126 men, 4230 women; mean age, 67 ± 6.2 years) who provided complete exposure data at baseline. All participants provided written informed consent.

Outcome ascertainment

All-cause mortality was obtained through consultation of the National Death Registry, review of medical records, and contacts with family physicians. The outcomes were annually ascertained and verified by a Clinical Events Committee, whose members were blinded to the intervention group. The analysis included cases confirmed by the Clinical Events Committee between October 1, 2003 and December 31, 2012.

Exposure measurements

Overall diet quality was estimated by the degree of adherence to the MedDiet, as measured by a 14-point Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MedDiet score) [24]. Participants were asked to complete the form by answering 12 questions on food consumption frequencies and 2 questions on food intake habits. The food items, which were characteristic of the traditional MedDiet, were scored 0 or 1, generating a final score from 0 to 14.

The validated Spanish version of the Minnesota Leisure-Time Physical Activity questionnaire [25, 26] was used to measure the amount and intensity of LTPA. Initially created in 1978 [27], this instrument is designed to estimate the total energy expenditure during LTPA. Energy expenditure was measured in metabolic equivalent task per minutes per day (METs min/day), calculated by multiplying the number of METs previously assigned to each activity by the minutes per day spent performing that specific activity. LTPA levels were classified as follows: light (≤ 4 METs), moderate (4–5.5 METs), and vigorous (≥ 6 METs). Participants completed the questionnaire by indicating the number of days and minutes per day during the previous week and year they had practiced each of the 67 suggested activities.

Both the 14-point Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener and the Minnesota LTPA questionnaire were applied at baseline and yearly during follow-up, and a cumulative average for each was calculated.

Covariables

A baseline 47-item general questionnaire and an annual follow-up questionnaire were used to collect information about lifestyle, education level, health condition, history of illness, and medication use. More than basic education was defined as having an education level above primary school. Energy intake was recorded by a validated 137-item food-frequency questionnaire [28, 29]. Trained and certified nurses used a calibrated beam scale and a wall-mounted stadiometer to measure weight and height, respectively. BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by the squared of height (m2). Blood pressure measurements were taken in triplicate with a semiautomatic oscillometer (HEM-705CP, Omron). Participants were considered to have hypertension, diabetes, or hypercholesterolemia if they had a previous diagnosis of these conditions and/or where being treated with antihypertensive, antidiabetic, or lipid-lowering medication, respectively. All covariables were annually recorded and the cumulative averages of BMI and energy intake were calculated.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the cumulative average of the annually measured exposure and covariables (energy intake and BMI) to reduce within-person variation. To estimate the combined association of LTPA and MedDiet adherence with mortality, we created a dummy variable that joint tertiles (low = 1st tertile; moderate = 2nd tertile, and high = 3rd tertile) of the LTPA and the MedDiet scores, generating a single variable with nine categories (Online Resource, Table 4). For analysis purposes, we merged the following categories: (1) low level of LTPA and moderate MedDiet adherence (1st tertile LTPA + 2nd tertile MedDiet score) with moderate level of LTPA and low MedDiet adherence (2nd tertile LTPA + 1st tertile MedDiet score); (2) low level of LTPA and high MedDiet adherence (1st tertile LTPA + 3rd tertile MedDiet score) with high level of LTPA and low MedDiet adherence (3rd tertile LTPA + 1st tertile MedDiet score); and (3) high levels of LTPA and moderate MedDiet adherence (3rd tertile LTPA + 2nd tertile MedDiet score) with moderate levels of LTPA and high MedDiet adherence (2nd tertile LTPA + 3rd tertile MedDiet score).

General linear modelling procedures were used to compare general characteristics of the study population according to these joint categories of LTPA and MedDiet score. General linear modelling is basically an ANOVA factorial analysis, in which a continuous dependent variable is determined by two or more factors. Polynomial contrasts determined p for linear trend for continuous variables, with a post hoc Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Chi-square tests were used to determine p for linear trend for categorical variables.

Cox proportional hazards regression models were fitted to determine the separate and joint association of LTPA (total, low, and moderate-to-vigorous) and adherence to the MedDiet with all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality. All final models were adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, smoking, intervention group, education level, BMI, and energy intake. Sensitivity analyses excluded events that occurred during the first year of follow-up and was stratified by intervention group and by sex.

Cox proportional hazards regression models with cubic spline functions were fitted to analyse the dose–response relationship between adherence to the MedDiet; total, low, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA; and all-cause mortality. Extreme values, defined as equal or more than three standard deviations of total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA, were eliminated from this analysis, which was performed with the “gam” R package, version 3.0.2. All other statistical analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows v. 22 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

The median and interquartile range (IQR) for the cumulative average of total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA was 196 (101–322), 89 (35–159), and 56 (8–175) METs min/day, respectively. Based on the subset of participants (n = 1699) for whom baseline data were available, the variance of light, moderate, and intense LTPA could be explained by slow walking (93.1%), by gardening and walking (85.5%), and by stair climbing, bicycling, and swimming (51.1%), respectively. The mean (SD) for the MedDiet score was 9.6 (1.6) points. During a mean follow-up of 6.8 years, 498 (6.8%) deaths were reported.

General characteristics according to joint categories of LTPA and adherence to the MedDiet are outlined in Table 1. Highest combined levels of LTPA and of the MedDiet score were directly associated with energy intake, education level, and proportions of men and current smokers. The opposite was observed for age, BMI, and the proportions of participants with type 2 diabetes and hypertension.

In age- and sex-adjusted models, the highest tertiles of adherence to the MedDiet, total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA were associated with a 44, 28, 22, and 43% lower risk for all-cause mortality, respectively, compared with the lowest tertiles (Table 2). The magnitude of the association was stronger for MedDiet adherence, compared to levels of total LTPA. Controlling for diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, smoking, intervention group, education level, BMI, and energy intake did not further affect the direction and magnitude of these associations.

The hazard of mortality decreased with the joint categories of increasing levels of LTPA and adherence to the MedDiet (Table 3). We observed a 73% decrease in mortality between the extremes of these categories (low levels of LTPA and low MedDiet adherence versus high levels of LTPA and high MedDiet adherence). A comparable risk reduction of all-cause mortality was observed after replacement of total LTPA by light and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA in categories combined with MedDiet adherence (Table 3). The effect size was somewhat stronger for moderate-to-vigorous LTPA compared to light LTPA.

Sensitivity analyses revealed no significant differences after stratification by sex and intervention group and the exclusion of cases that occurred during the first year of follow-up (Online Resource, Table 5).

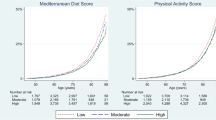

The dose–response curve of LTPA (total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA) and all-cause mortality had a curvilinear shape (nonlinear p < 0.01 for all) with a greater benefit at the lower end of the activity ranges (Fig. 1). The strongest benefit was reached after 400, 300, and 100 METs min/day of total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA, respectively (Fig. 1). The dose–response association of adherence to the MedDiet and all-cause mortality showed a strong inverse linear association.

Dose–response association between all-cause mortality and a total LTPA, b moderate-to-vigorous LTPA, c light LTPA, and d adherence to the Mediterranean diet. All models were adjusted for sex, age, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, hypertension, smoking, intervention group, education level, body mass index, and energy intake. Additionally, we mutually adjusted LTPA (total, moderate-to-vigorous, and light) with adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and light LTPA with moderate-to-vigorous LTPA. LTPA leisure-time physical activity, measured in METs min/day

The association of cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality with joint categories of LTPA and adherence to the MedDiet is shown in Table 6 (Online Resource). The effect size was comparable between the two causes of mortality.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we found an association of higher levels of LTPA and MedDiet adherence, separately and joined, with lower rates of all-cause mortality in older adults at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Risk reduction was similar for the separate and joint associations of light and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA with MedDiet adherence, with a slightly stronger magnitude for moderate-to-vigorous LTPA, compared to light LTPA.

Despite sound evidence for the beneficial impact of LTPA on mortality risk reduction in the general population [3, 4, 12, 30, 31], less evidence is available for different LTPA intensities in older populations. The HALE project, including 2339 elderly European individuals, reported a 37% decrease in the 10-year risk of all-cause mortality in those participants in the intermediate and highest tertile of total LTPA [17]. Pooled data from six large prospective cohorts showed that 75 min of self-reported brisk walking per week was associated with a 19% mortality risk reduction in adults aged 21–90 years [32]. Higher levels of self-reported physical activity related to a greater mortality risk reduction. Similar findings were reported for objectively measured MVPA in US adults [12]. It is of interest that the curvilinear dose–response relationship between accelerometer-measured MVPA and mortality reported by Matthews and colleagues [12] is similar to our data based on self-reported MVPA.

The ageing phenomenon is characterized by a series of morphological and physiological changes that lead to a reduction in physical activity performance, especially at high intensities but also at moderate intensities. Therefore, light physical activity may be a more feasible option for older adults. Consequently, the promotion of light-intensity physical activities could be a helpful strategy to improve health and reduce the risk of premature mortality. Recent evidence indicates that self-reported and objectively measured light physical activity might have greater health benefits than previously thought [12, 33,34,35]. Our findings add further evidence for the impact of light physical activities on the risk of all-cause mortality. A finding of particular importance is that mortality risk was reduced by 22% in the second tertile of light physical activity, which corresponds to approximately 40 min of slow walking daily, 30 min of daily slow bicycling or 30 min of light yard work. These activities could be a more feasible option for older adults than regular engagement in MVPA. An even stronger risk reduction of 58% was observed for the joint category of moderate levels of light physical activity (equivalent to 40 min of slow walking per day) and moderate MedDiet adherence (equivalent to 9.0–10.4 points). Furthermore, our dose–response analysis revealed that light-intensity activities are more important at the lower end of the dose–response curve, which is in concordance with previous findings by Matthews and colleagues [12]. The present study found no further risk reduction beyond 300 METs of light LTPA, independently of moderate-to-vigorous LTPA (equivalent to 2 h of slow walking per day).

Our finding that MedDiet adherence is inversely associated with all-cause mortality has been previously reported in older adults [16,17,18]. However, there is little prior evidence about the joint association of MedDiet adherence and physical activity with mortality [19]. Behrens and colleagues found inverse associations of physical activity and MedDiet adherence, separately and joined, with all-cause mortality in a large cohort of adults with a mean age of 62.5 years at the beginning of follow-up. The effect of the joint association of physical activity and MedDiet adherence was slightly higher than the separate associations of these lifestyle factors with all-cause mortality. Additionally, the magnitude of these associations was significantly lower than that reported in the present study. Dichotomous versus tertile coding of lifestyle categories might partially explain this difference. In our study, the top category of high levels of LTPA and high MedDiet adherence showed the highest effect size. However, our finding that intermediate categories of LTPA and adherence to the MedDiet reduced all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality risk by 53, 35, and 69%, respectively, is of importance because it implies that even relatively slight changes in these lifestyle factors were associated with substantial health benefits.

Physical activity could decrease the mortality risk, mainly by decreasing the risk of non-communicable diseases, such as coronary heart disease, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, colon and breast cancer, depression, neurological diseases and muscle-skeletal diseases [36,37,38,39]. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet could further increase life expectancy by adding its benefits of decreasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases, cancer, neurogenerative diseases, and diabetes [14, 15].

We acknowledge the potential for misclassification because recall and reporting biases are inherent limitations of self-reported data. However, random misclassification would attenuate the association of the exposure variables with the outcome. Therefore, it is likely that our results underestimate the true relationship of LTPA and MedDiet adherence with mortality. The strengths of this study are the large sample of older adults, the annually repeated measurements of the variables that best represent long-term exposure and also reduce within-person variation, and the use of validated questionnaires.

In summary, adherence to the MedDiet and total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA were inversely associated with mortality. Joint categories of high MedDiet adherence and high levels of total, light, and moderate-to-vigorous LTPA showed the highest effect size. Our findings add further evidence for the promotion of light physical activity among older adults. Randomized clinical studies, such as the ongoing PREDIMED Plus trial [40], are necessary to provide causal evidence on the effect of a combined physical activity and dietary intervention on health outcomes.

References

Kontis V, Bennett JE, Mathers CD et al (2017) Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet 6736:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32381-9

World Health Organization (2015) World report on ageing and health. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Kelly P, Kahlmeier S, Götschi T et al (2014) Systematic review and meta-analysis of reduction in all-cause mortality from walking and cycling and shape of dose response relationship. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 11:132. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-014-0132-x

Ekelund U, Steene-Johannessen J, Brown WJ et al (2016) Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 388:1302–1310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30370-1

Li F, Hou L, Chen W et al (2015) Associations of dietary patterns with the risk of all-cause, CVD and stroke mortality: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Br J Nutr 113:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711451400289X

Onvani S, Haghighatdoost F, Surkan PJ et al (2017) Adherence to the Healthy Eating Index and Alternative Healthy Eating Index dietary patterns and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease and cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hum Nutr Diet 30:216–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/jhn.12415

Araceta-Bartrina J, Arija Val V, Maiz Aldalur E et al (2016) Guías alimentarias para la población española (SENC, diciembre 2016); la nueva pirámide de la alimentación saludable. Nutr Hosp 33:1–48. https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2013.28.sup4.6783

(2011) French National Nutrition and Health Program 2011–2015. http://solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/PNNS_UK_INDD_V2.pdf

Agriculture USD of (2015) Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. Dietary guidelines and MyPlate. http://www.choosemyplate.gov/dietary-guidelines

Kahlmeier S, Wijnhoven TM, Alpiger P et al (2015) National physical activity recommendations: systematic overview and analysis of the situation in European countries. BMC Public Health 15:133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1412-3

Hupin D, Roche F, Gremeaux V et al (2015) Even a low-dose of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity reduces mortality by 22% in adults aged ≥ 60 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 49:1262–1267. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-094306

Matthews CE, Keadle SK, Troiano RP et al (2016) Accelerometer-measured dose-response for physical activity, sedentary time, and mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr 104:1424–1432. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.135129

Schröder H (2007) Protective mechanisms of the Mediterranean diet in obesity and type 2 diabetes. J Nutr Biochem 18:149–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.05.006

Dinu M, Pagliai G, Casini A, So F (2017) Mediterranean diet and multiple health outcomes: an umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. Eur J Clin Nutr 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2017.58

Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Wang A et al (2016) Effects of the Mediterranean diet on cardiovascular outcomes—a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 11:e0159252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159252

Limongi F, Noale M, Gesmundo A et al (2017) Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and all-cause mortality risk in an elderly Italian population: data from the ILSA study. J Nutr Health Aging 21:505–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-016-0808-9

Knoops KTB, de Groot LCPGM., Kromhout D et al (2004) Mediterranean diet, lifestyle factors, and 10-year mortality in elderly European men and women: the HALE project. JAMA 292:1433–1439. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ieb.0000150381.96671.6b

Zaslavsky O, Zelber-Sagi S, Hebert JR et al (2017) Biomarker-calibrated nutrient intake and healthy diet index associations with mortality risks among older and frail women from the Women’s Health Initiative. Am J Clin Nutr 105:1399–1407. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.116.151530

Behrens G, Fischer B, Kohler S et al (2013) Healthy lifestyle behaviors and decreased risk of mortality in a large prospective study of U.S. women and men. Eur J Epidemiol 28:361–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-013-9796-9

Estruch R, Martínez-González MA, Corella D et al (2006) Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on cardiovascular risk factors. A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 145:1–11. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-145-1-200607040-00004

Martínez- González M, Corella D, Salas-Salvado J et al (2012) Cohort profile: design and methods of the PREDIMED study. Int J Epidemiol 41:377–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq250

The PREDIMED network. http://www.predimed.es/. Accessed 27 Feb 2017

BioMed Central. ISRCTN registry. http://www.isrctn.com/. Accessed 22 March 2017

Schroder H, Fitó M, Estruch R et al (2011) A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr Nutr Epidemiol 141:1140–1145. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.110.135566

Elosua R, Marrugat J, Molina L et al (1994) Validation of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire in Spanish men. The MARATHOM Investigators. Am J Epidemiol 139:1197–1209

Elosua R, Garcia M, Aguilar A et al (2000) Validation of the Minnesota Leisure Time Physical Activity Questionnaire in Spanish Women. Med Sci Sport Exerc 32:1431–1437

Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B et al (1978) A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis 31:741–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(78)90058-9

Fernández-Ballart JD, Piñol JL, Zazpe I et al (2010) Relative validity of a semi-quantitative food-frequency questionnaire in an elderly Mediterranean population of Spain. Br J Nutr 103:1808–1816. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114509993837

De la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Vázquez Ruiz Z, Bes-Rastrollo M et al (2010) Reproducibility of an FFQ validated in Spain. Public Health Nutr 13:1364–1372. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980009993065

Borgundvaag E, Janssen I (2017) Objectively measured physical activity and mortality risk among American adults. Am J Prev Med 52:e25–e31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.017

Ekelund U, Ward H, Norat T et al (2015) Physical activity and all-cause mortality across levels of overall and abdominal adiposity in European men and women: the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study (EPIC). Am J Clin Nutr 101:613–621. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.114.100065

Moore SC, Patel AV, Matthews CE et al (2012) Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med 9:e1001335. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001335

Matthews CE, Moore SC, Sampson J et al (2015) Mortality benefits for replacing sitting time with different physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 47:1833–1840. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000621

Ensrud KE, Blackwell TL, Cauley JA et al (2014) Objective measures of activity level and mortality in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc 62:2079–2087. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13101

Fishman EI, Steeves JA, Zipunnikov V et al (2016) Association between objectively measured physical activity and mortality in NHANES. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48:1303–1311. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000885

Moore SC, Lee I-M, Weiderpass E et al (2016) Association of leisure-time physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA Intern Med 176:816. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548

Lee I-M, Shiroma EJ, Lobelo F et al (2012) Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet 380:219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61031-9

Murtagh EM, Nichols L, Mohammed MA et al (2014) Walking to improve cardiovascular health: a meta-analysis of randomised control trials. Lancet 384:545. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62180-2

Fortes C, Mastroeni S, Sperati A et al (2013) Walking four times weekly for at least 15 min is associated with longevity in a Cohort of very elderly people. Maturitas 74:246–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.001

PREDIMED PLUS Network. http://www.predimedplus.com. Accessed 30 March 2017

Acknowledgements

CIBERESP and CIBEROBN are initiatives of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) of Spain, which are supported by FEDER funds (CB06/03). Also supported by ISCIII, the official funding agency for biomedical research of the Spanish government, through grants provided to research networks specifically developed for the trial (RTIC G03/140 and RD 06/0045) through CIBEROBN, and by grants from Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares (CNIC 06/2007), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria-Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (PI04-2239, PI05/2584, CP06/00100, PI07/0240, PI07/1138, PI07/0954, PI 07/0473, PI10/01407, PI10/02658, PI11/01647, and PI11/02505; PI13/00462), Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (AGL-2009-13906-C02 and AGL2010-22319-C03), Fundación Mapfre 2010, Consejería de Salud de la Junta de Andalucía (PI0105/2007), Public Health Division of the Department of Health of the Autonomous Government of Catalonia, Generalitat Valenciana (ACOMP06109, GVA-COMP2010-181, GVACOMP2011-151, CS2010-AP-111, and CS2011-AP-042), and the Navarra Regional Government (27/2011). MF was supported by a joint contract of the ISCIII and Health Department of the Catalan Government (Generalitat de Catalunya) (CP 06/00100). The Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero and Hojiblanca SA (Málaga, Spain), California Walnut Commission (Sacramento, CA), Borges SA (Reus, Spain), and Morella Nuts SA (Reus, Spain) donated the olive oil, walnuts, almonds, and hazelnuts, respectively, used in the study. We appreciate the English revision by Elaine M. Lilly, Ph.D.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GMC and HS conceived the project; MAM, JS-S, DC, RE, MF, EGG, MF, JL, FA, LS-M, JAT, XP, ER, OC, AD-L, and MR-C conducted the research; CMG, IS, and HS analysed the data; CMG wrote the manuscript: CMG and HS had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript; all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests related to the study.

Ethics and consent

The Institutional Review Board of all participating centres approved the study protocol and the trial was conducted following the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cárdenas-Fuentes, G., Subirana, I., Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A. et al. Multiple approaches to associations of physical activity and adherence to the Mediterranean diet with all-cause mortality in older adults: the PREvención con DIeta MEDiterránea study. Eur J Nutr 58, 1569–1578 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1689-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1689-y