Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to assess the relative efficacy and safety of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and azathioprine (AZA) as maintenance therapies for lupus nephritis.

Methods

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance therapies in patients with lupus nephritis were included. We performed a Bayesian random-effects network meta-analysis to combine the direct and indirect evidence from RCTs.

Results

Ten RCTs comprising 884 patients were included in the study. Although the difference was not statistically significant, MMF showed a trend toward a lower relapse rate compared with AZA (odds ratio [OR] 0.72, 95% credible interval [CrI] 0.45–1.22). Similarly, tacrolimus showed a trend toward a lower relapse rate compared with AZA (OR 0.85, 95% CrI 0.34–2.00). Ranking probability based on the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA) indicated that MMF had the highest probability of being the best treatment based on the relapse rate, followed by CNI and AZA. The incidence of leukopenia in the MMF and CNI groups was significantly lower than that in the AZA group (OR 0.12, 95% CrI 0.04–0.34; OR 0.16, 95% CrI 0.04–0.50; respectively). Fewer patients with infections were observed in the MMF group than in the AZA group, although the difference was not statistically significant. The analysis of withdrawals due to adverse events showed a similar pattern.

Conclusion

Lower relapse rates combined with a more favorable safety profile suggest that CNI and MMF are superior to AZA as maintenance treatments in lupus nephritis patients.

Zusammenfassung

Zielsetzung

Ziel dieser Studie war es, die relative Wirksamkeit und Sicherheit von Calcineurin-Inhibitoren (CNI), Mycophenolatmofetil (MMF) und Azathioprin (AZA) als Erhaltungstherapie bei Lupusnephritis zu bewerten.

Methoden

Eingeschlossen wurden randomisierte kontrollierte Studien (RCTs), welche die Wirksamkeit und Sicherheit von CNI, MMF und AZA als Erhaltungstherapie bei Patienten mit Lupusnephritis untersuchten. Wir führten eine Bayessche Netzwerk-Metaanalyse mit zufälligen Effekten durch, um die direkte und indirekte Evidenz aus den RCTs zu kombinieren.

Ergebnisse

Es wurden 10 RCTs mit 884 Patienten in die Studie aufgenommen. Obwohl der Unterschied statistisch nicht signifikant war, zeigte MMF im Vergleich zu AZA die Tendenz zu einer niedrigeren Rückfallrate (Odds-Ratio [OR] 0,72; 95 % Konfidenzintervall [KI] 0,45‑1,22). Auch bei Tacrolimus zeigte sich ein Trend zu einer niedrigeren Rückfallrate im Vergleich zu AZA (OR 0,85; 95 % KI 0,34‑2,00). Die Rangwahrscheinlichkeit auf Grundlage der Fläche unter der kumulativen Rangkurve (SUCRA) zeigte, dass MMF die höchste Wahrscheinlichkeit hatte, die beste Behandlung auf der Grundlage der Rückfallrate zu sein, gefolgt von CNI und AZA. Die Inzidenz von Leukopenien war in der MMF- und CNI-Gruppe signifikant niedriger als in der AZA-Gruppe (OR 0,12; 95 % KI 0,04‑0,34; OR 0,16; 95 % KI 0,04‑0,50; jeweils). In der MMF-Gruppe wurden weniger Patienten mit Infektionen beobachtet als in der AZA-Gruppe, obwohl der Unterschied statistisch nicht signifikant war. Die Analyse der Abbrüche aufgrund von unerwünschten Ereignissen ergab ein ähnliches Muster.

Schlussfolgerung

Geringere Rückfallraten in Verbindung mit einem günstigeren Sicherheitsprofil deuten darauf hin, dass CNI und MMF als Erhaltungstherapie bei Patienten mit Lupusnephritis gegenüber AZA überlegen sind.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Up to 60% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have renal impairment, and lupus nephritis remains the major cause of morbidity and mortality in SLE [29, 35]. The treatment strategy for lupus nephritis consists of an induction phase to induce remission and a maintenance phase to prevent recurrence and the development of end-stage renal disease [1]. Cyclophosphamide (CYC) therapy has long been considered the gold standard for inducing renal remission and preventing flare-ups. However, significant drug-related adverse effects, such as an increased risk of severe infections, bone marrow suppression, malignancy, and ovarian toxicity, outweigh these benefits [30]. Other immunosuppressive drugs used to treat lupus nephritis include mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), tacrolimus, and azathioprine (AZA).

Several studies have examined the efficacy and safety of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) MMF, and AZA as maintenance therapies in patients with lupus nephritis [5,6,7,8, 12, 17, 19, 20, 28, 36]. All these drugs have demonstrated significant efficacy as maintenance therapies in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for lupus nephritis. One meta-analysis found that MMF was as effective as AZA when administered for maintenance therapy and less hazardous for the treatment of lupus nephritis [13]. A second study, however, found no benefit of using MMF over AZA as maintenance therapy for this indication [26]. CNI, MMF, and AZA were investigated in a small number of RCTs to examine their relative efficacy and safety as maintenance treatments for lupus nephritis, but the findings were equivocal owing to the small sample sizes. Even if the available data from head-to-head comparisons are insufficient, network meta-analysis may assess the comparative effectiveness of various medicines and integrate data from a network of RCTs to help in decision-making [23, 24]. The present study employed a network meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance treatments for lupus nephritis.

Methods

Identification of eligible studies and data extraction

We performed an exhaustive search for studies that examined the efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance treatments for patients with lupus nephritis. A literature search was performed in PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register to identify available articles (up to December 2022). The following keywords and subject terms were used in the search: “lupus nephritis,” “maintenance treatment,” “tacrolimus,” “cyclosporine,” “mycophenolate mofetil,” and “azathioprine.” All references were reviewed to identify additional studies that were not included in the electronic databases. RCTs were included if the study met the following criteria: 1) compared CNI or MMF with AZA, or CNI with MMF as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis; 2) provided endpoints for the efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA; and 3) included patients with biopsy-proven lupus nephritis class III, IV, or V. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) inclusion of duplicate data and 2) lack of adequate data for inclusion. The efficacy outcome was relapse. The definitions of relapse were based on the criteria used in each trial (Table 1 and 2). The safety outcome was the number of patients withdrawn due to adverse events (AEs), infection, leukopenia, or doubling of serum creatinine. The following information was extracted from each study: first author, year of publication, study region, and kidney biopsy class; number of patients treated with CNI, MMF, or AZA; and the efficacy and safety outcomes of the drugs. We quantified the methodological qualities of the four studies using the Jadad scores [18]. Network meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the PRISMA statement [27].

Evaluation of statistical associations for network meta-analysis

The efficacy and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA for maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis were ordered according to the probability of being ranked as the best-performing agent. A random effects model was used as a conservative method, and a Bayesian network meta-analysis was conducted using NetMetaXL [2] and WinBUGS statistical analysis program version 1.4.3 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Institute of Public Health, Cambridge, UK). The Markov chain Monte Carlo method was used to obtain a pooled effect size [3]. All chains were run with 10,000 burn-in iterations followed by 10,000 monitoring iterations. The information on relative effects was converted to the probability that a treatment was best, second best, and so on, with the ranking of each treatment (called the surface under the cumulative ranking curve or SUCRA) expressed as a percentage, ranging between 100% and 0%, with 100% and 0% indicating that the treatment is the best and worst, respectively [31]. The summary estimates were presented in league tables by ranking the treatments in order of the most pronounced impact on the outcome under consideration based on the SUCRA [31]. We reported the pairwise odds ratio (OR) and 95% credible interval (CrI) adjusted for the multiple-arm trials. Pooled results were considered statistically significant if 95% of the CrI did not contain a value of 1.

Test for inconsistency and sensitivity analysis

Inconsistency refers to the extent of disagreement between the direct and indirect evidence [10]. Assessment of inconsistency is important for conducting a network meta-analysis [16]. We plotted the posterior mean deviance of the individual datapoints in the inconsistency model against their posterior mean deviance in the consistency model to assess network inconsistency between the direct and indirect estimates in each loop [34]. A sensitivity test was performed by comparing the random and fixed effects models.

Results

Studies included in the meta-analysis

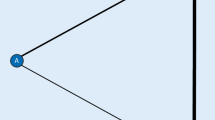

A total of 967 studies were identified using electronic or manual searches, of which 16 were selected for full-text review based on the title and abstract details. However, six of the 16 studies were excluded: one because it included patients with lupus nephritis without renal biopsy, [9] one was not an RCT (cohort [4]), four studies included data only on AZA without a comparison group including tacrolimus, MMF, or AZA [11, 28], and two studies included duplicate data [32, 33]. Thus, 10 RCTs, including a total of 884 patients, met the inclusion criteria ([5,6,7,8, 12, 17, 19, 20, 28, 36]; Fig. 1). There were three interventions, including eight studies of MMF, nine of AZA, and three of CNI, for the network meta-analysis. The Jadad scores for all studies except two were 3–4, indicating high study quality. The relevant features of the studies included in this meta-analysis are presented in Table 1 and 2.

Evidence network diagram of comparisons for network meta-analysis. The width of each edge is proportional to the number of randomized controlled trials comparing each pair of treatments, and the size of each treatment node is proportional to the number of randomized participants (sample size). AZA azathioprine, CNI calcineurin inhibitor, MMF mycophenolate mofetil

Network meta-analysis of the efficacy of CNI, MMF, and AZA in RCTs

We considered the number of relapses as the efficacy outcome. MMF was listed at the top left of the diagonal of the league table (Fig. 2) because it was associated with the most favorable SUCRA for efficacy outcomes, whereas AZA was listed at the bottom right of the diagonal of the league table because it was associated with the least favorable results (Fig. 2; Table 3). MMF showed a trend toward a lower relapse rate compared with AZA (odds ratio [OR] 0.72, 95% credible interval [CrI] 0.45–1.22; Fig. 2 and 3). The number of relapses were lower in the CNI group than in the AZA group (OR 0.85, 95% CrI 0.34–2.00; Fig. 2 and 3). However, the number of relapses did not differ significantly between the three drugs. This may be partly explained by the low statistical power from a relatively small number of patients who had relapses in each group and from the small number of studies in this network meta-analysis. The ranking probability based on SUCRA indicated that MMF had the highest probability of being the best treatment based on the renal relapse rate, followed by CNI and AZA (Table 3).

League tables showing the results of the network meta-analyses comparing the effects of all drugs, including odds ratio (OR) and 95% credible interval (CrI). OR < 1 means the treatment in the top left is better. a Relapse; b withdrawal due to adverse events; c infection; d leukopenia; e doubling serum creatine. MMF mycophenolate mofetil, AZA azathioprine

Bayesian network meta-analysis results of randomized controlled studies on the relative efficacy and safety of calcineurin inhibitor (CNI), mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and azathioprine (AZA) based on renal relapse, withdrawal due to adverse events (AEs), number of infections, leucopenia, and doubling serum creatine. a Relapse, b withdrawal due to AE, c infection, d leukopenia, e doubling serum. OR odds ratio, CrI 95% credible interval

Network meta-analysis of the safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA in RCTs

We considered the number of patient withdrawals due to AEs, infection, leukopenia, and doubling of serum creatinine as the safety outcome. The number of patient withdrawals due to AEs did not differ significantly between the interventions (Fig. 2 and 3). However, the incidence of infection in the CNI and MMF groups tended to be lower than that in the AZA group (OR 0.39, 95% CrI 0.09–1.92; OR 0.56, 95% CrI 0.19–1.63; Fig. 2 and 3). The ranking probability based on SUCRA indicated that CNI had the highest probability of being the most tolerable treatment, followed by MMF and AZA (Table 3). Fewer patients with infections were observed in the CNI and MMF groups than in the AZA group, although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 2 and 3). The incidence of leukopenia in the MMF and CNI groups was significantly lower than that in the AZA group (OR 0.12, 95% CrI 0.04–0.34; OR 0.16, 95% CrI 0.04–0.50; Fig. 2 and 3). The ranking probability based on SUCRA indicated that MMF had the highest probability of being the safest treatment based on leukopenia incidence, followed by CNI and AZA (Table 3). The doubling of serum creatinine levels did not differ significantly among the interventions (Fig. 2; Table 3).

Inconsistency and sensitivity analysis

Inconsistency plots assessing network inconsistencies between direct and indirect estimates showed a low possibility that these inconsistencies may significantly affect the network meta-analysis results. In addition, the random and fixed effects model results provided the same trend for OR, indicating that the results of this network meta-analysis are robust (Fig. 3).

Discussion

The best long-term results for lupus nephritis require identification of the optimal maintenance medication after remission induction [1]. The relative effectiveness and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance therapies in patients with lupus nephritis were examined in this network meta-analysis. MMF, which is probably better than AZA, may be linked to the highest likelihood of preventing renal recurrence in these patients as maintenance therapy, followed by CNI. However, there were no significant differences in the efficacy. In terms of safety, there was no difference in the number of withdrawals owing to AEs among the drugs. Tolerability seemed to be higher with CNI and MMF because AE withdrawals were less common than with AZA. MMF and CNI were similarly linked to a significantly lower prevalence of leukopenia than AZA.

Unlike the previous network meta-analysis by Lee et al., [21] the current analysis eliminated CYC and included four new trials. Only one study has been conducted on CYC. However, in terms of relative effectiveness, our findings are comparable to those of the CYC study [21]. Furthermore, our findings are consistent with recent meta-analyses that found that MMF was less harmful than AZA [13]. Similar studies have been published on the management of lupus nephritis [14, 15]. Both studies were meta-analyses of RCTs on the induction and maintenance of lupus nephritis. MMF prevented relapse more successfully than AZA during maintenance treatment, with no increase in clinically meaningful AEs. In contrast to the two previous studies, our network meta-analysis focused on lupus nephritis maintenance treatment and included analyses of the relative effectiveness and safety of immunosuppressive medications such as MMF, AZA, and CNI. Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies comparing MMF to AZA in terms of renal relapse and safety. However, our findings provide important information that was missing from earlier conventional meta-analyses about the relative effectiveness and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA as maintenance therapies for lupus nephritis.

However, due to several limitations of our research, our findings should be considered with caution. First, there were only two RCTs on tacrolimus in the included literature, resulting in limited sample sizes. Second, diversity in the study design and patient characteristics may have influenced the results of this network meta-analysis. Third, this study focused only on effectiveness and safety, measuring the number of patients who experienced renal relapse, severe infection, leukopenia, doubling blood creatine, and withdrawal due to AEs. Consequently, the findings of this study did not address all elements of drug efficacy and safety. Fourth, the results are complicated by a number of factors, including the percentage of patients with class IV lupus nephritis, varying definitions of renal relapse, induction therapy employed, severity of the illness, drug dosage, and duration of follow-up. We were not able to adjust the variables because of a lack of data.

Nevertheless, this meta-analysis has a few advantages. In various trials, patients with lupus nephritis ranged in number from 42 to 227, while this particular investigation comprised 884 participants. By improving the statistical power and resolution, we were able to generate data that were more precise than those revealed in individual research. When direct head-to-head comparisons are either unavailable or inadequate, network meta-analysis allows for an indirect comparison of different treatments, maximizing the use of all available data [22, 25]. The relative effectiveness and safety of MMF, CNI, and AZA in maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis are shown in this study. In conclusion, we discovered that CNI and MMF were the most effective maintenance therapies for patients with lupus nephritis and that MMF had the best chance of minimizing the risk of leukopenia, infections, and withdrawal due to AEs. MMF and CNI maintenance treatments are preferable over AZA in these patients owing to the outcome of decreased renal relapse rates. Further research is needed to definitively assess the relative effectiveness and safety of CNI, MMF, and AZA in a broader group of patients in order to find the best maintenance treatment for lupus nephritis.

References

Almaani S, Meara A, Rovin BH (2017) Update on lupus nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12(5):825–835

Brown S, Hutton B, Clifford T et al (2014) A Microsoft-Excel-based tool for running and critically appraising network meta-analyses—an overview and application of NetMetaXL. Syst Rev 3(1):110

Caldwell DM, Ades A, Higgins J (2005) Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ 331(7521):897

Chan T, Tse K, Tang CS et al (2005) Long-term outcome of patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis treated with prednisolone and oral cyclophosphamide followed by azathioprine. Lupus 14(4):265–272

Chan TM, Li FK, Tang CS et al (2000) Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 343(16):1156–1162

Chan TM, Tse KC, Tang CS et al (2005) Long-term study of mycophenolate mofetil as continuous induction and maintenance treatment for diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol 16(4):1076–1084

Chen W, Liu Q, Chen W et al (2012) Outcomes of maintenance therapy with tacrolimus versus azathioprine for active lupus nephritis: a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Lupus 21(9):944–952

Contreras G, Pardo V, Leclercq B et al (2004) Sequential therapies for proliferative lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 350(10):971–980

Decker JL, Klippel JH, Plotz PH et al (1975) Cyclophosphamide or azathioprine in lupus glomerulonephritis. A controlled trial: results at 28 months. Ann Intern Med 83(5):606–615

Dias S, Welton NJ, Sutton AJ et al (2013) Evidence synthesis for decision making 4 inconsistency in networks of evidence based on randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Making 33(5):641–656

Donadio JV Jr., Holley KE, Wagoner RD et al (1974) Further observations on the treatment of lupus nephritis with prednisone and combined prednisone and azathioprine. Arthritis Rheum Care Res 17(5):573–581

Dooley MA, Jayne D, Ginzler EM et al (2011) Mycophenolate versus azathioprine as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis. N Engl J Med 365(20):1886–1895

Feng L, Deng J, Huo DM et al (2013) Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis. Nephrology 18(2):104–110

Henderson L, Masson P, Craig JC et al (2012) Treatment for lupus nephritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 12

Henderson LK, Masson P, Craig JC et al (2013) Induction and maintenance treatment of proliferative lupus nephritis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Kidney Dis 61(1):74–87

Higgins J, Jackson D, Barrett J et al (2012) Consistency and inconsistency in network meta-analysis: concepts and models for multi-arm studies. Res Synth Methods 3(2):98–110

Houssiau FA, D’Cruz D, Sangle S et al (2010) Azathioprine versus mycophenolate mofetil for long-term immunosuppression in lupus nephritis: results from the MAINTAIN Nephritis Trial. Ann Rheum Dis 69(12):2083–2089

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D et al (1996) Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 17(1):1–12

Jiang WXX, Fang J‑A (2002) Efficacy of mycophenolatemofetil in patients with diffuse proliferative lupus nephritis. Chin J Integr Tradit West 3:218–221

Kaballo BG, Ahmed AE, Nur MM et al (2016) Mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine for maintenance treatment of lupus nephritis. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 27(4):717

Lee Y, Song G (2017) Comparative efficacy and safety of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, and cyclophosphamide as maintenance therapy for lupus nephritis. Z Rheumatol 76(10):904–912

Lee Y, Song G (2015) Relative efficacy and safety of tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and cyclophosphamide as induction therapy for lupus nephritis: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lupus 24(14):1520–1528

Lee YH (2018) An overview of meta-analysis for clinicians. Korean J Intern Med 33(2):277

Lee YH (2016) Overview of network meta-analysis for a rheumatologist. J Rheum Dis 23(1):4–10

Lee YH, Song GG (2016) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of duloxetine, pregabalin, and milnacipran for the treatment of fibromyalgia: a Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int 36(5):663–672

Maneiro JR, Lopez-Canoa N, Salgado E et al (2014) Maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis with mycophenolate or azathioprine: systematic review and meta-analysis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 53(5):834–838

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Moroni G, Doria A, Mosca M et al (2006) A randomized pilot trial comparing cyclosporine and azathioprine for maintenance therapy in diffuse lupus nephritis over four years. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1(5):925–932

Park DJ, Joo YB, Bang S‑Y et al (2022) Predictive factors for renal response in lupus nephritis: a single-center prospective cohort study. J Rheum Dis 29(4):223–231

Petri M (2004) Cyclophosphamide: new approaches for systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 13(5):366–371

Salanti G, Ades A, Ioannidis JP (2011) Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol 64(2):163–171

Sundel R, Solomons N, Lisk L (2012) Aspreva Lupus Management Study (ALMS) Group. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in adolescent patients with lupus nephritis: evidence from a two-phase, prospective randomized trial. Lupus 21(13):1433–1443

Tamirou F, D’Cruz D, Sangle S et al (2015) Long-term follow-up of the MAINTAIN Nephritis Trial, comparing azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil as maintenance therapy of lupus nephritis. Ann Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206897

Valkenhoef G, Lu G, Brock B et al (2012) Automating network meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods 3(4):285–299

Waldman M, Appel GB (2006) Update on the treatment of lupus nephritis. Kidney Int 70(8):1403–1412

Zhang Q, Xing P, Ren H et al (2022) Mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus compared with azathioprine in long-term maintenance treatment for active lupus nephritis. Front Med: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-021-0849-2

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Y.H. Lee and G.G. Song declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Additional information

Redaktion

Ulf Müller-Ladner, Bad Nauheim

Uwe Lange, Bad Nauheim

Scan QR code & read article online

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y.H., Song, G.G. Relative efficacy and safety of calcineurin inhibitor, mycophenolate mofetil, and azathioprine as maintenance therapies for lupus nephritis: a network meta-analysis. Z Rheumatol 83 (Suppl 1), 140–147 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-023-01374-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-023-01374-x