Abstract

Objectives

To gain information about the efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs as first-, second-, and third-line treatment of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM).

Methods

112 treatment cycles of 63 patients with dermatomyositis (n = 23), polymyositis (n = 33), overlap syndromes (n = 4), and undifferentiated connective tissue diseases (n = 3) were analyzed by retrospective chart analysis. Data regarding muscle strength, muscle enzymes, treatment duration, and treatment discontinuation were collected.

Results

Azathioprine (38 cycles) and methotrexate (MTX; 24 cycles) were applied significantly longer than glucocorticoid monotherapy (9 cycles; 25 ± 21, 26 ± 29 and 7 ± 4 months, respectively; p < 0.05). MTX and azathioprine achieved a significant reduction of serum creatine kinase (CK), with MTX showing more marked effects. Treatment cycles with immunosuppressants other than MTX or azathioprine (n = 22) or with combinations of immunosuppressive drugs (n = 19) were mostly applied as third-line therapy, indicating their application in more refractory cases. Significant improvement of muscle strength was confined to MTX and azathioprine and to the first-line treatment. 8% of MTX patients withdrew due to the lack of efficacy, compared with 29% of patients taking azathioprine and 6 of 9 patients taking glucocorticoid monotherapy. In the 12 patients with Jo-1 syndrome, MTX treatment was effective for a longer time than azathioprine (44 ± 21 months vs. 27 ± 24 months, p < 0.05).

Conclusion

Our data confirm the effectiveness of MTX and azathioprine in the treatment of inflammatory myopathies and stress the importance of a potent first-line therapy.

Zusammenfassung

Zielstellung

Ziel der Analyse war die Prüfung der Effizienz von immunsuppressiven Medikamenten als Erst‑, Zweit-, und Drittlinientherapie der idiopathischen inflammatorischen Myopathien (IIM).

Methoden

Retrospektiv erfolgte die Analyse von 112 Behandlungszyklen bei 63 Patienten mit Dermatomyositis (n = 23), Polymyositis (n = 33), Überlappungssyndromen (n = 4) und undifferenzierten Bindgewebserkrankungen (n = 3). Daten zu Muskelkraft, Muskelenzymen, Behandlungsdauer und Gründen des Therapieabbruchs wurden erfasst.

Ergebnisse

Azathioprin (38 Zyklen) und Methotrexat (MTX, 24 Zyklen) wurden signifikant länger angewendet als eine Glukokortikoid-Monotherapie (9 Zyklen; 25 ± 21, 26 ± 29 und 7 ± 4 Monate, p < 0,05). MTX und Azathioprin bewirkten eine signifikante Reduktion der Serumkreatinkinase (CK), die bei MTX ausgeprägter war. Behandlungsregime mit anderen Immunsuppressiva als MTX oder Azathioprin (n = 22) sowie die Kombination mehrerer Immunsuppressiva (n = 19) wurden meist als Drittlinientherapie angewendet und waren somit refraktären Fällen vorbehalten. Signifikante Verbesserungen der Muskelkraft traten nur bei MTX- und Azathioprinbehandlung und nur nach dem ersten Therapiezyklus auf. Wegen mangelnder Effektivität brachen 8 % der MTX-behandelten Patienten und 29 % der Patienten unter Azathioprin die Behandlung ab, ebenso 6 der 9 Patienten unter Glukokortikoid-Monotherapie. Bei den 12 Patienten mit Jo-1-Syndrom war die MTX-Behandlung länger effektiv als die Gabe von Azathioprin (44 ± 21 Monate vs. 27 ± 24 Monate, p < 0,05).

Schlussfolgerung

Die vorliegenden Daten bestätigen die Effektivität von MTX und Azathioprin in der Behandlung von IIM und betonen die Bedeutung einer potenten Erstlinientherapie.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIM) are autoimmune disorders characterized by a proximal muscle weakness, inflammatory changes of the musculature, and, in a significant proportion, the presence of myositis-associated autoantibodies. This group includes dermatomyositis (DM) and polymyositis (PM), as well as syndromes overlapping with other connective tissue diseases. A more recently described entity is the immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy associated with the use of statins, but also with the occurrence of cancer and other connective tissue diseases [1]. The prevalence of 8.7 per 100,000 for PM and DM together underscores the rarity of these disorders [2].

Although a recent clinical study has added evidence for the efficacy of immunosuppressive drugs in juvenile IIM [3], few clinical trials exist for the treatment of adult DM and PM (reviewed in [4, 5]). Therefore, retrospective analyses of the clinical course of patients with IIM may provide important information concerning the effectiveness of conventional immunosuppressive drugs. Although glucocorticoid monotherapy is often the first choice of treatment, well-known side effects argue against their prolonged application in higher doses. Here, we report data of patients with IIM treated in a single tertiary care center, in which it was common to start with the combination of glucocorticoids and an immunosuppressive substance immediately after the diagnosis was made.

Materials and methods

Data of patients with IIM treated at the University Hospital of Halle (Saale) between 1995 and 2008 were obtained by chart review. All patients were of Caucasian origin and fulfilled at least four of the diagnostic criteria of Bohan and Peter [6]. The involvement of internal organs such as pulmonary and cardiac manifestations was recorded. Since the degree of muscle strength before and after therapy was not always documented in a standardized manner in the charts, muscle weakness was classified as 1: normal strength, 2: mild to moderate weakness, 3: severe weakness. The documentation included the level of creatine kinase (CK), the presence of autoantibodies specific for IIM, and the results of muscle MRI, muscle biopsy, and electromyography (EMG).

For the definition of a treatment cycle with a defined drug, a clear-cut time point for the treatment start was required as well as a documented reason for discontinuation (e. g., lack of efficacy, adverse events, remission). A treatment cycle was eligible for the analysis only if CK levels and information about physical function at the start and the end of treatment were available in the patient chart. For ongoing treatments, CK levels and muscle strength had to have been documented within the previous 3 months.

For the drug survival analyses, patients with DM and PM were merged into one sample. Treatment cycles were divided into subgroups: methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine (AZA), and monotherapy with glucocorticoids (GC). Due to small sample sizes, the subgroup “other treatments” contained patients treated with cyclophosphamide, immunoglobulins, cyclosporine A, mycophenolate mofetil, and rituximab. The subgroup “combination therapy” contained, among others, patients treated with both azathioprine and cyclosporine (n = 4; see Table 1).

In addition, the efficacy of the treatment was analyzed according to the treatment cycle. First-line, second-line, and third-line treatment were evaluated separately.

Statistical analysis of the therapeutic cycles was performed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Kruskal–Wallis test) as well as non-parametric testing by means of the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test. Kaplan–Meier analysis was applied for the investigation of drug survival.

Results

Data of 63 patients were collected from a sample of 152 patients with myositis. Patients with inclusion body myositis (n = 41) or necrotizing myopathy on biopsy (n = 10), patients who did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria [6] (n = 17), and patients without a treatment cycle according to the predefined criteria (n = 20) were excluded. Baseline characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 2.

All patients presented with muscle weakness, all DM patients revealed typical dermatological signs. 12 patients with PM were positive for Jo-1 antibodies. Patients underwent a median of two treatment cycles (range: 1–7), reaching a total of 112 cycles.

With 38 treatment cycles recorded, the application of azathioprine was the most frequent therapy in our cohort. A total of 24 treatment cycles were documented for MTX, 9 cycles were performed with GC monotherapy (see Table 2).

63 cycles were classified as first-line, 25 as second-line, 24 as third-line treatment. The third-line arm also contained all treatment cycles of higher number (n = 8). The mean treatment duration of the first-, second-, and third-line cycles were 19, 23, and 8 months, respectively, with the third-line cycles being significantly shorter than the other cycles (p < 0.05). In the 23 patients with DM, 36% of treatment cycles were second or third line (13 of 36 cycles), compared with 49% in patients with PM (32 of 65 cycles). With 28 applications, azathioprine was the preferred drug for the first-line therapy, followed by MTX (12) and steroid monotherapy (8). In second-line cycles, MTX was used most frequently, followed by azathioprine. Third-line regimens were dominated by combination treatment (n = 9) and other therapies (n = 10; see Table 1).

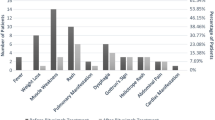

The mean duration of treatment for MTX was 25 ± 21 months (mean ± SD) and comparable with azathioprine (26 ± 29 months). Both drugs were used significantly longer than a steroid monotherapy (7 ± 4 months, p < 0.05). Drug survival curves are displayed in Fig. 1. 41% of 24 patients receiving MTX discontinued therapy during the observation period. In the other groups, the discontinuation rate was higher: 50% of all azathioprine patients, 78% of patients receiving steroids. 68% of other treatments and 63% of combination therapies were discontinued. In addition, MTX-treated patients had the lowest rate of treatment cessation due to lack of efficacy (see Table 3).

In the patients with Jo-1 syndrome, the duration of MTX treatment (5 cycles) was significantly longer than with azathioprine (6 cycles): 44 ± 21 months versus 27 ± 24 months (mean ± SD; p < 0.05).

MTX-treated patients received a mean dose of prednisolone of 49 ± 31 mg/day at the beginning of the cycle, which was lowered to 7.8 ± 4.3 mg/day at the end. The respective figures for azathioprine were 55 ± 33 and 11.4 ± 15 mg/day (mean ± SD). A tendency toward lower prednisolone doses at the end of the cycle was noticed for MTX, which did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09).

The change in CK levels during the treatment is shown in Fig. 2. Significant changes occurred in the MTX, azathioprine, and combination treatment groups. A decrease of CK levels below the upper limit of normal was observed merely in the MTX group (Fig. 2a). With respect to the cycle number, a significant decrease of CK values was seen during the first treatment cycle only (Fig. 2b). In the first treatment cycle, MTX led to a decrease in the CK levels from a baseline value of 58.2 ± 70.9 to 1.6 ± 1.2 µmol/ls (mean ± SD) at the end of the cycle, the figures for AZA (n = 28) were 44.7 ± 54.45 and 24.5 ± 65.9 µmol/ls,Footnote 1 respectively. Both results were statistically significant (p < 0.05). All other subgroups and the sample sizes of the second and third cycles were too small to allow a further splitting of the analysis (data not shown).

Levels of serum creatine kinase (CK) before treatment and at the end of the treatment cycle with methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine (AZA), glucocorticoids (GC), other treatments, and combination therapies (a) and separated after first, second, and third treatment cycle (irrespective of the subtype of IIM and the applied drug; b). Asterisks indicate significant changes of CK levels between start and end of the cycle (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). The horizontal line indicates the upper limit of normal

A marked improvement in muscle weakness was documented during MTX treatment, with a change from 2 ± 1 to 1.4 ± 1.1, p < 0.005, and for azathioprine (2.1 ± 1.2 to 1.7 ± 1.2, p < 0.05; mean + SD). All other treatment groups did not achieve a significant improvement of physical function. With respect to the treatment cycle, a significant improvement of the muscle weakness was observed only after the first cycle (from 2.0 ± 0.9 to 1.7 ± 1.2, p < 0.05), but not for later cycles.

Discussion

The data presented here reflect the conditions of everyday clinical practice. Despite the limitations inherent to an observational study, our analyses allow some cautious conclusions. During the observation period, most patients required only one or two treatment cycles, with both cycles given for a comparable length of time. This supports the assumption that the applied treatments were effective long term, and that a significant proportion of patients already reached an improvement of physical function and CK levels with the first treatment regimen. Our data, however, do not allow an assessment of the dynamics of the therapeutic response, since CK values after 3 or 6 months could not be analyzed systematically. Third-line therapies had a shorter duration of treatment, indicating the selection of patients with refractory disease. The latter postulation is also supported by the finding that third-line treatments were not accompanied by significant reductions in CK levels or improvements of muscle strength.

In our cohort, azathioprine and MTX were the preferred drugs for the first-line treatment. In a retrospective cohort, it is difficult to analyze the specific reasons that prompted the physician to choose between both alternatives. This choice may be empirical to a significant extent or may depend on personal experience. However, a variety of covariates could influence this decision: whereas the concomitant impairment of liver or kidney function would argue against the use of MTX, the appearance of arthritis in patients with Jo-1 syndrome could provoke some rheumatologists to use this compound, although evidence for efficacy of MTX with respect to this specific manifestation is lacking. AZA is a well-established drug in connective tissue diseases. In contrast to MTX, the compound can be prescribed to women planning to get pregnant and is applicable in patients with slightly impaired renal function.

In our patient sample, both therapies allowed the reduction of corticosteroids over time and could be taken for more than 2 years in the majority of patients. Both led to a reduction of CK levels and to an increase in muscle strength. Our data agree with previous reports of a steroid-sparing effect of MTX and a beneficial effect of this compound on muscle strength [7]. A controlled trial demonstrated only minor improvements in newly diagnosed PM patients receiving azathioprine or placebo in addition to background steroids for 3 months [8]. However, this benefit became more obvious in the 3‑year follow-up [9], a timeframe that is closer to the conditions in our cohort. In addition, azathioprine shows some clinical improvement in a case series of patients with myositis-associated inflammatory lung disease [10].

All of our patients receiving MTX and azathioprine were treated with glucocorticoids in parallel. Therefore, our study is not able to discern the effect size of both immunosuppressants in addition to the steroid treatment. Nevertheless, cycles with MTX and azathioprine were more effective than the therapy with glucocorticoids alone with respect to treatment duration, CK levels, and physical function. However, this notion is limited by the small sample size of patients receiving glucocorticoid monotherapy.

Although glucocorticoids are the backbone of treatment in IIM, the evidence for steroid treatment is scarce, especially with respect to the starting dose, the duration of treatment, and the optimal combination regimen [4, 5]. Significantly, the subtype of IIM is of influence with respect to the responsiveness to a glucocorticoid monotherapy: in a case series of 100 patients, those with dermatomyositis and overlap syndrome responded best (87 and 93%, respectively), whereas steroids alone were effective in 50% of the PM patients only [11]. This argues for the hypothesis that treatment of PM may be more demanding compared to DM and overlap syndromes. In our cohort, more PM patients required second- or third-line treatments than DM patients, a finding that points in the same direction. Recently, a small study of patients with partial response to glucocorticoids could not find a significant effect of on-top treatment with either MTX or cyclosporine compared with placebo in IIM patients [12]. This is in contrast to a larger randomized study in juvenile DM that reported a favorable effect of MTX and cyclosporine in comparison to steroids alone [3]. In the same study, MTX had a more marked steroid-sparing effect and a better safety profile than cyclosporine. The latter finding also agrees with a smaller study in adult IIM patients, in which MTX showed a more rapid improvement of CK values and the tendency toward a more favorable clinical outcome compared to cyclosporine A [13].

Our data also indicate subtle advantages for the treatment of IIM with MTX in comparison with azathioprine. CK levels reached normal values under MTX treatment only. MTX had the least rate of discontinuation due to lack of efficacy, and showed a tendency to allow a more marked steroid reduction compared with azathioprine. To our best knowledge, there are no sufficient data regarding the direct comparison between MTX and azathioprine in IIM therapy. A double-blind controlled trial involving both drugs has been published as an abstract only [14]. The authors also came to the conclusion that MTX had advantages over azathioprine. Another retrospective analysis revealed that MTX and azathioprine were more effective in IIM patients with early treatment start [15]. Our data point in the same direction by showing that third-line treatment is less effective with respect to treatment duration, physical function, and CK levels than earlier treatment courses. In the same report, MTX was more effective than azathioprine in men compared with women, an observation that could not be seen on our smaller sample (data not shown). In addition, a better treatment response to MTX than to azathioprine was reported in subgroups positive for Jo-1 antibodies [15]. In the Jo-1-positive patients of our cohort, the duration of MTX treatment was significantly longer compared with azathioprine, pointing toward a more favorable outcome under MTX as well. A randomized controlled study of IIM to investigate the efficacy of MTX and glucocorticoids compared with glucocorticoid monotherapy is currently underway [16].

Our analysis has several limitations. Treatment duration was used as a surrogate parameter for treatment efficacy, since our data did not allow the application of the recently developed core set measures to assess myositis disease activity [17]. In addition, we did not screen for anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase antibodies. Therefore, it was not specifically addressed whether our cohort contained a subset of patients with statin-associated myopathy [18]. However, the majority of our patients underwent muscle biopsy, and patients with necrotizing myopathy were excluded from our cohort. Thus, the likelihood of bias in this respect should be very low. Significantly, our analysis did not differentiate between DM and PM, due to the small numbers of patients. Therefore, possible advantages of MTX or AZA in one of these subgroups remain obscure. It is also not clear from our data whether a certain sequence of immunosuppressants (e. g., MTX followed by AZA or vice versa) offers any therapeutic advantage. In addition, only three of our patients received rituximab, too few for a valid subgroup analysis. Although a large controlled trial of rituximab in adult DM/PM and juvenile DM has led to ambiguous results [19], rituximab has been successful in clinical practice, especially in patients with anti-synthetase syndrome, both with respect to muscle as well as pulmonary involvement [20].

In summary, our data indicate that both MTX and azathioprine are valuable treatment options for patients with DM and PM. The analysis also argues for the hypothesis that MTX may have some advantages over azathioprine. In clinical practice, MTX may also have a better versatility in that the drug can be used orally and parenterally. In addition, rheumatoid arthritis trials have proven that MTX can be safely combined with rituximab, whereas the respective data with azathioprine are lacking. Further clinical trials are necessary to clarify which of the conventional immunosuppressive drugs has the highest potential for the treatment of IIM.

Notes

Normal range 2,85 (Males), equivalent to 171 IU/l, and 2,42 (Females), equivalent to 145 IU/l.

References

Mammen AL, Chung T, Christopher-Stine L et al (2011) Autoantibodies against 3‑hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase in patients with statin-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 63:713–721. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30156

Dobloug C, Garen T, Bitter H et al (2015) Prevalence and clinical characteristics of adult polymyositis and dermatomyositis; data from a large and unselected Norwegian cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 74:1551–1556. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205127

Ruperto N, Pistorio A, Oliveira S et al (2016) Prednisone versus prednisone plus ciclosporin versus prednisone plus methotrexate in new-onset juvenile dermatomyositis: a randomised trial. Lancet 387:671–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01021-1

Oddis CV (2016) Update on the pharmacological treatment of adult myositis. J Intern Med 280:63–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12511

Moghadam-Kia S, Aggarwal R, Oddis CV (2015) Treatment of inflammatory myopathy: emerging therapies and therapeutic targets. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 11:1265–1275. https://doi.org/10.1586/1744666X.2015.1082908

Bohan A, Peter JB (1975) Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 292:344–347. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm197502132920706

Newman ED, Scott DW (1995) The use of low-dose oral methotrexate in the treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol 1:99–102

Bunch TW, Worthington JW, Combs JJ et al (1980) Azathioprine with prednisone for polymyositis. A controlled, clinical trial. Ann Intern Med 92:365–369

Bunch TW (1981) Prednisone and azathioprine for polymyositis: long-term followup. Arthritis Rheum 24:45–48

Douglas WW, Tazelaar HD, Hartman TE et al (2001) Polymyositis-dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164:1182–1185. https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.164.7.2103110

Troyanov Y, Targoff IN, Tremblay JL et al (2005) Novel classification of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies based on overlap syndrome features and autoantibodies: analysis of 100 French Canadian patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 84:231–249

Ibrahim F, Choy E, Gordon P et al (2015) Second-line agents in myositis: 1‑year factorial trial of additional immunosuppression in patients who have partially responded to steroids. Rheumatology 54:1050–1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keu442

Vencovsky J, Jarosova K, Machacek S et al (2000) Cyclosporine A versus methotrexate in the treatment of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Scand J Rheumatol 29:95–102

Miller JW, Walsh Y et al (2002) Randomized double blind controlled trial of methotrexate and steroids compared with azathioprine and steroids in the treatment of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. J Neurol Sci 199(Suppl 01):S53

Joffe MM, Love LA, Leff RL et al (1993) Drug therapy of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: predictors of response to prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate and a comparison of their efficacy. Am J Med 94:379–387

Vencovsky J, Institute of Rheumatology Prague (2016) Combined Treatment of Methotrexate + Glucocorticoids Versus Glucocorticoids Alone in Patients With PM and DM (Prometheus). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00651040 (last update posted: May 12, 2016)

Rider LG, Werth VP, Huber AM et al (2011) Measures of adult and juvenile dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and inclusion body myositis: Physician and Patient/Parent Global Activity, Manual Muscle Testing (MMT), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)/Childhood Health Assessment Questionnaire (C-HAQ), Childhood Myositis Assessment Scale (CMAS), Myositis Disease Activity Assessment Tool (MDAAT), Disease Activity Score (DAS), Short Form 36 (SF-36), Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ), physician global damage, Myositis Damage Index (MDI), Quantitative Muscle Testing (QMT), Myositis Functional Index-2 (FI-2), Myositis Activities Profile (MAP), Inclusion Body Myositis Functional Rating Scale (IBMFRS), Cutaneous Dermatomyositis Disease Area and Severity Index (CDASI), Cutaneous Assessment Tool (CAT), Dermatomyositis Skin Severity Index (DSSI), Skindex, and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Arthritis Care Res 63(Suppl 11):S118–S157. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20532

Musset L, Allenbach Y, Benveniste O et al (2016) Anti-HMGCR antibodies as a biomarker for immune-mediated necrotizing myopathies: a history of statins and experience from a large international multi-center study. Autoimmun Rev 15:983–993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.023

Oddis CV, Reed AM, Aggarwal R et al (2013) Rituximab in the treatment of refractory adult and juvenile dermatomyositis and adult polymyositis: a randomized, placebo-phase trial. Arthritis Rheum 65:314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.37754

Andersson H, Sem M, Lund MB et al (2015) Long-term experience with rituximab in anti-synthetase syndrome-related interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology 54:1420–1428. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kev004

Acknowledgements

We kindly thank Ms. Ulrike Loebe for her contribution to extracting the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

G. Keyßer, S. Zierz, and M. Kornhuber declare that they have no competing interests.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Redaktion

U. Müller-Ladner, Bad Nauheim

U. Lange, Bad Nauheim

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keyßer, G., Zierz, S. & Kornhuber, M. Treatment of adult idiopathic inflammatory myopathies with conventional immunosuppressive drugs. Z Rheumatol 78, 183–189 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-018-0471-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-018-0471-0