Abstract

Aims

Heart failure (HF) guidelines recommend treating all patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) with quadruple therapy, although they do not establish how to start it. This study aimed to evaluate the implementation of these recommendations, analyzing the efficacy and safety of the different therapeutic schedules.

Methods and results

Prospective, observational, and multicenter registry that evaluated the treatment initiated in patients with newly diagnosed HFrEF and its evolution at 3 months. Clinical and analytical data were collected, as well as adverse reactions and events during follow-up.

Five hundred and thirty-three patients were included, selecting four hundred and ninety-seven, aged 65.5 ± 12.9 years (72% male). The most frequent etiologies were ischemic (25.5%) and idiopathic (21.1%), with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 28.7 ± 7.4%. Quadruple therapy was started in 314 (63.2%) patients, triple in 120 (24.1%), and double in 63 (12.7%). Follow-up was 112 days [IQI 91; 154], with 10 (2%) patients dying. At 3 months, 78.5% had quadruple therapy (p < 0.001). There were no differences in achieving maximum doses or reducing or withdrawing drugs (< 6%) depending on the starting scheme. Twenty-seven (5.7%) patients had any emergency room visits or admission for HF, less frequent in those with quadruple therapy (p = 0.02).

Conclusion

It is possible to achieve quadruple therapy in patients with newly diagnosed HFrEF early. This strategy makes it possible to reduce admissions and visits to the emergency room for HF without associating a more significant reduction or withdrawal of drugs or significant difficulty in achieving the target doses.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The incidence of heart failure (HF) continues to increase, partly due to the high prevalence of cardiovascular (CV) risk factors and the aging population [1]. Despite improved therapies and care organization around HF units, mortality remains high [2, 3]. Furthermore, despite the stabilization of hospital admissions, especially in those under 75 years [4], the annual readmission rate for CV causes is still more than 30% [2], which impacts prognosis and represents a high cost for the health system [5].

Over the past few years, several clinical trials have been published and added new evidence to the treatment of HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF), demonstrating a significant reduction in CV mortality and HF admission [6, 7]. A meta-analysis published in 2021 showed the added benefit of quadruple therapy with beta-blockers (BB), dual angiotensin II and neprilysin receptor inhibitors (ARNI), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), and sodium–glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i)8 [8].

HF guidelines, both European and American, recommend early initiation of treatment with these four pharmacological groups in all patients with HFrEF, increasing the doses of the drugs to the maximum tolerated doses as quickly as possible [9, 10]. However, there is no specific mention of how to implement this quadruple therapy, leaving the treating physician to choose the treatment schedule, depending on their clinical experience and the characteristics of the patients [11].

This study aims to evaluate the early implementation of quadruple therapy in clinical practice in newly diagnosed patients with HFrEF and the differences in efficacy and safety depending on the treatment schedule initiated.

Methods

Study population

We performed a national, multicentre, non-randomized, prospective registry (TIDY-HF), in which cardiologists of 32 hospitals participated (Fig. 1 of supplementary material), 77% with an HF unit accreditedy [12] (54% specialized, 25% community, and 21% advanced). All patients with newly diagnosed HFrEF were consecutively included: during hospitalization, in the outpatient clinic, or in the emergency room department. The diagnosis was established following the criteria of the cardiologist responsible for the patient according to clinical guidelines [10]. The date of diagnosis was defined as the date of echocardiographic diagnosis. Recruitment took place between October 2021 and March 2022, with a follow-up of at least 3 months after diagnosis.

Inclusion criteria were: (a) age > 18 years and (b) newly diagnosed with HFrEF, defined as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 40% in an echocardiogram. Exclusion criteria were: (a) allergy or absolute contraindication to any of the drugs included in the quadruple therapy; (b) systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 100 mmHg; (c) estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) < 30 mL/min; (d) potassium (K) > 5.2 mEq/L; (e) expected valvular or coronary intervention in the next 6 months; (f) life expectancy < 1 year.

The cardiologist determined each patient's treatment schedule and follow-up according to the local protocol and the current scientific evidence, recommending at least one visit a month and 3 months after the baseline visit [10].

Variables included

We included different variables: (1) clinical: age, sex, CV risk factors, heart rate (HR), blood pressure (BP), weight, height, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, and HF etiology; (2) echocardiographic [13]: LVEF estimated by Simpson method, right ventricular function estimated by tricuspid annulus plane systolic displacement (TAPSE), diastolic function and significant valvulopathies; (3) laboratory parameters: creatinine, GFR by chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration formula (CKD-EPI), sodium (Na), potassium (K), urea, carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125) and amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide type B portion (NTproBNP); (4) previous medical treatment with: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARB), BB, MRA, SGLT2i, and loop diuretics; (5) initial pharmacological treatment after HF treatment and during follow-up, dose, modifications or discontinuation of treatment; (6) clinical events during follow-up: admissions or visits to the emergency department (HF, CV, and other causes), death, implanted cardiac desfibrillator (ICD) or cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) implantation, coronary revascularisation or valve intervention. For patients randomized during hospitalization or emergency room visit, data were recorded before discharge and in those randomized in the outpatient clinic on the day of the visit. Treatment with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASi) included an ACEi, an ARB, or an ARNI.

Objectives

The study's primary objective was to determine the percentage of newly diagnosed patients with HFrEF with quadruple therapy after the baseline visit and 3 months after diagnosis, according to clinical practice guideline recommendations [10]. The secondary objective was to analyze the efficacy (maximum doses achieved) and safety (adverse clinical events and those related to treatment) of the different treatment schedules.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (or median and interquartile interval (IQI)), and qualitative variables as frequency and percentage. Continuous quantitative variables were compared using Student's t test (comparing means of two groups) or analysis of variance (ANOVA) (more than two groups) and the Wilcoxon test for variables not following a normal distribution (according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Chi-square for qualitative variables and ANOVA for quantitative variables were used to estimate the differences between the four treatment groups.

Logistic regression was used to establish the factors independently related to starting all four drug groups, reaching quadruple therapy at 3-month follow-up, and reaching the maximum dose of each group at 3-month follow-up. Variables with a p < 0.1 in the univariate analysis were included in each model, and the variable with the highest p was removed one by one until all those remaining in the model were statistically significant (backward stepwise). The results of the regression with odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval are presented. A statistical significance level of 0.05 (bilateral) was established for all statistical tests. Statistical analysis was performed with the SPSS 22.0 statistical package (IBM, New York, United States of America).

Ethics and quality of the registry

This study adhered to the STROBE recommendations for observational studies [14]. The registry was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the ethics committee's approval. All patients provided written informed consent. Data were recorded in an electronic data collection notebook, anonymizing all patients' data. Only the principal investigators can consult the total data of the included patients.

Results

Patients included

A total of 533 patients with a new diagnosis of HFrEF were included. Four hundred and thirty-nine (82.4%) were diagnosed during hospitalization, fifty-five (10.3%) in the outpatient clinic, and thirty-nine (7.3%) in the emergency department. The median time between the diagnosis and baseline visit was 7 days [IQI 0; 17]. Median follow-up was 112 days [IQI 91; 154], with ten (2%) patients dying during this period and two (0.4%) lost to follow-up. The median time between the baseline visit and the first-month visit was 32 days [IQI 26; 38], and between the baseline visit and the 3-month visit, 96 days [IQI 84; 111].

Taking into account the different drug combinations with a class I indication in clinical practice guidelines [10], a total of 11 treatment regimens were differentiated (Table 1 of supplementary material). For the current analysis, patients receiving the 4 most frequent treatment regimens were selected, and the rest (36 patients) were excluded, considering a total of 497 patients (Table 1). Of these, 314 (63.2%) started quadruple therapy (4G), 120 (24.1%) triple (3G), and 63 (12.7%) double (2G). The two 3G regimens that were selected as the most frequent were: a) RAASi, BB, and MRA in 64 (12.9%) patients (3 Ga); and b) RAASi, BB, and SGLT2i in 56 (11.3%) (3 Gb). In the 2G scheme, 5 different drug combinations were included, the most frequent being the combination of RAASi and BB in 41 (8.2%) patients.

General characteristics of the population

The mean age of the selected population was 65.5 years (SD:12.9), with 72% male. Of the patients included, 57.9% were hypertensive, 33.4% were diabetic, and 49.3% had a history of dyslipidemia. At diagnosis, 42.1% of all patients received a RAASi and 11.1% an MRA. There were no differences between groups in the presence of CV risk factors, except for diabetes, which was more frequent in the 3G group with SGLT2i (3 Gb) (Table 1). No patient has an ICD or a TRC previously to HF diagnosis.

BP and HR were higher in those starting the 3 Gb and 2G treatment regimens. Worse renal function and higher K levels were also observed in patients starting 3 Gb or 2G.

Treatment evolution during follow-up and clinical episodes

Treatment data at baseline were available for all included patients, and treatment data at 1 month and 3 months for 492 (98.9%) and 475 (95.7%) patients, respectively (Table 2 and Fig. 2 of supplementary material). The percentage of patients receiving RAASi and BB at baseline was above 95% and remained unchanged during the follow-up period. The most commonly used RAASi was ARNI, with a significant increase at 1 month (79.3%; p = 0.01) and 3 months (79.4%; p = 0.03). There was a reduction in the percentage of patients on ARB during follow-up, with no significant change in the percentage of patients on ACEi.

The percentage of patients receiving MRA at the baseline visit was 78.7% and increased at subsequent visits to 86.5% at 3 months (p < 0.001). 76.3% of patients received SGLT2i at baseline, increasing to 91.4% at 3 months (p < 0.001). In contrast, the number of patients on loop diuretics decreased from 73.2% at baseline to 52.4% at 3 months (p < 0.001).

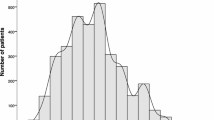

The percentage of patients achieving 4G increased from 63.2% at baseline to 74.2% at 1 month (p < 0.001) and 78.5% at 3 months (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). The number of drug groups received at month 3 was significantly related to the starting schedule (p < 0.001), such that 93.7% of those who started 4G at baseline were receiving 4G at the month 3 visit, compared to 61% in the 3 Ga group, 44.6% in the 3 Gb group, and 51.7% in the 2G group (Table 3).

There were no significant differences in the percentage of patients reaching the maximum dose at 1 month or 3 months for any drug groups (RAASi, BB, MRA) according to the starting schedule (Fig. 2). In the first month of follow-up, 4.4% of patients required reduced or withdrawn RAASi, 5.3% of BB, 5.8% of MRA, and 0.8% of SGLT2i. There were no significant differences in the starting regimen, except for MRA, where a more significant reduction or withdrawal was observed in the 3 Ga group (p = 0.039). Of those who remained on these drugs, 4.8% of patients with RAASi, 5.2% with BB, 5.6% with MRA, and 1.0% with SGLT2i required tapering or withdrawal by the third month, with no significant differences depending on the starting regimen.

SBP reduced during the follow-up (basal: 119.0 (SD:18.3) mmHg, 1 month 115.8 (SD:18.9) mmHg and 3 months 115.7 (SD:19.1) mmHg; p < 0.01), with no differences between the four treatment schedules. There were also no differences in the percentage of patients requiring dose reduction or drug withdrawal due to hypotension. The percentage of patients with AF was reduced during the follow-up from the baseline in 4G (28.3% vs 18.2%; p = 0.03), 3G (26.1% vs 15.5%; p = 0.03), and 2G (25.8% vs 15.3%; p = 0.04) groups. Finally, we observed a significant reduction in NTproBNP values during the follow-up (baseline: 4364.1 (SD:7795.6) pg/ml; 1 month 2397.6 (SD: 3859.8) pg/mL; 3 months 1868.0 (SD: 3668.0) pg mL; p < 0.001). When the different treatment schedules were compared, a more significant reduction of NTproBNP was observed in the 3 Ga group (p = 0.047).

During follow-up, ten (2.0%) patients died (0.4% in the first month). Ninety-nine (20.8%) had an emergency room visit or admission for any cause (13.8% in the first month), 13.8% for CV causes, of which 5.7% for HF (3.5% in the first month) (Table 4). At 1 month, the number of visits to the emergency department or admissions for any cause was lower in the 4G treatment regimen (p = 0.03), with no significant differences at 3 months (p = 0.07). HF decompensations at 1 month showed no significant differences depending on the treatment regimen, but at 3 months were significantly less frequent in the 4G group than in the other groups. During the 3 months follow-up, 15 patients (3.2%) received an ICD and 12 (2.6%) a CRT.

Predictors of baseline treatment schedule

Patients with higher body weight at baseline (OR: 1.02; 95% CI 1.00–1.03) and larger left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (OR: 1.02; 95% CI 1.00–1.04) were more likely to initiate 4G. GFR was identified as a relevant factor for 4G implementation. Patients with worse GFR were less likely to initiate 4G (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.55–0.98), and those with better GFR were more likely to achieve 4G at 3 months (OR 1.01, 95% CI 1.00–1.02).

Predictors of quadruple therapy implementation at follow-up

Of the patients who initiated 4G, 281 (93.7%) have maintained it at 3 months (Table 3). Initiating 4G at baseline was identified as the strongest predictor of receiving 4G at 3 months (OR:17.5; 95% CI 10.0–30.5). Diabetic patients (OR: 0.63; 95% CI 0.41–0.96) and those with higher NTproBNP values at baseline (OR: 0.97; 95% CI 0.94–1.00) were less likely to achieve 4G at the end of follow-up. Patients who attended more follow-up visits during the 3 months were more likely to achieve 4G (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.06–1.50). Predictors of reaching maximum doses at follow-up are listed in Table 2 of supplementary material. Peak doses achieved did not depend on the treatment schedule (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The main findings of the TIDY-HF registry are: (a) more than 60% of patients with newly diagnosed HFrEF were able to initiate all four drug groups with class I indication simultaneously in the first week after diagnosis, with almost 80% at 3 months; (b) the majority of patients initiating 4G maintain it at 3 months; (c) there appear to be no significant differences in safety profile or ability to reach maximum dose at 3 months depending on the initiation schedule; (d) initiation of 4G is associated with a reduction in the overall number of emergency room visits or admissions in the first month and the number of HF decompensations at 3 months (central illustration).

The HF guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommend the implementation of 4G in all patients with HFrEF [10] but do not specify how this should be done. An ESC position paper recommends individualizing the treatment regimen according to the patient's phenotype, although it only considers some aspects that influence treatment [11]. Other authors have proposed other treatment schedules [15, 16], although the order and form of dosing have not been resolved. In the TIDY-HF registry, more than 60% of patients could initiate 4G within the first week after diagnosis, with RAASi (mostly ARNI) and BB being the most frequent pharmacological groups. At 3 months, almost 80% of patients reached 4G, with a high implementation of MRA and especially SGLT2i. This supports the possibility of initiating and achieving quadruple therapy in the short term, ensuring the early benefit demonstrated by ARNI and SGLT2i [6, 17]. In our work, initiation of 4G was not dependent on NTproBNP, LVEF, or NYHA, in line with clinical practice guideline recommendations [10]. The fact that most patients were diagnosed during hospital admission may have favored the simultaneous initiation of several drugs. In addition, the absence of congestion allowed a progressive reduction in the dose of conventional diuretics, in a higher proportion than reported in other registries (8.3% vs. 20.8%), which could have impacted the reduction in CV mortality [18].

Initiation of 4G was safe, with 94% of patients maintaining 4G at 3 months. The rate of hospital admissions or emergency department visits was even lower in those on 4G. Withdrawal or dose reduction of drugs with class I indication was infrequent (< 6%), regardless of treatment schedule, and was higher in those patients admitted for any cause. This reinforces the need to develop a coordinated program of care for HF patients to avoid drug discontinuation during admissions.

The main limiting factor for starting or achieving 4G was CKD (33% of our cohort). In these patients, there was less use of an MRA at baseline and 3-month follow-up, but CKD did not limit the use of SGLT2i. Patients with cardiorenal syndrome have a poorer prognosis, so the development of cardiorenal units may help to optimize their management. Beldhuis I et al. published a review of these drugs' safety and prognostic benefit up to stage 3b, with little evidence in GFR < 30 mL/min [19]. The initial drop in GFR due to the use of high-dose diuretics during the acute episode or after initiation of some of these drugs, especially SGLT2i, should not be interpreted negatively and should not limit the implementation of 4G [19, 20]. K levels also limited the initiation of 4G, especially MRA. K-binders' use was low (2%), so their use should be considered to control K levels and optimize pharmacological treatment [21].

In diabetic patients, SGLT2i initiation or maintenance was more likely. BB initiation was more frequent in patients with AF (31% of the cohort) and those with elevated HF. The usefulness of BB in patients with HF and AF is controversial [22], yet their use is widespread based on their pathophysiological mechanism. On the other hand, the goal of an HR < 70 bpm in sinus rhythm should be pursued in all patients [23] (initial HR in our cohort of 76 bpm), and the use of BB is helpful for this purpose [24]. BP also did not limit 4G initiation in our study, although patients with lower values initially received an SGLT2i more frequently. Traditionally, ARNI has been associated with a higher rate of hypotension, and it has been shown that patients treated with ARNI did not discontinue RAASi more than those treated with enalapril, with the benefit of ARNI being significantly greater [25]. Recently, the STRONG-HF trial demonstrated the implementation of class I indication drugs after HF discharge (although it did not consider SGLT2i), reaching at least 50% of the maximum dose, with a rapid dosing protocol, is possible and is accompanied by a better short-term prognosis [26].

The percentage of patients reaching target doses was below 60% at 3 months, which was not dependent on the chosen treatment regimen, reinforcing the strategy of starting all four drug lines and then increasing their doses. Organizing the care process around the HF units is essential to achieve this goal. In our study, the number of visits to the HF unit determined the implementation and dose escalation of class I drugs. In the ETIFIC trial, which included 320 patients with newly diagnosed HFrEF, the critical role of the HF nurse specialist in optimizing treatment was already demonstrated, leading to a reduction in HF admissions [27].

Previous studies in our setting have reported a 1-month mortality in patients with HF of 5.3–10.4% and a readmission rate in that period of 9.7–9.9% [2, 3]. In the present study, both mortality and HF decompensations were significantly lower (0.4% and 3.5%, respectively), probably because a group of patients with a better prognosis (newly diagnosed HF) was selected because there was a higher proportion and dosage of treatments with class I indication and because of the broad participation of centers with a structured program of care for HF patients. In another Spanish registry, which included 2834 outpatients with HF, slightly lower use of drugs with prognostic benefit was also observed (RAASi 92.6%, BB 93.3%, MRA 74.5%), with a target dose attainment rate of less than 25% for all drug groups [28].

Our study has some limitations. First, it is a non-randomized study, with all the biases inherent to this type of study, although the homogeneous distribution of the patients included seems to support its external validity. Second, there is no information available on drug adherence, so the ability to draw robust conclusions on the superiority of specific schedules is limited, although close follow-up in HF units favors adherence. Finally, as this is a multicentre observational registry conducted in HF units, there may be a selection bias, making the results not extrapolate to all HF patients. Even so, this study shows that early implementation of 4G is possible, although the organization of the care process for HF patients is essential.

Conclusion

Quadruple therapy can be implemented in most patients with HFrEF in the first 3 months after diagnosis. Early initiation of quadruple therapy is not associated with increased drug reduction, withdrawal, or lower target doses in the short term compared to the other schedules. The use of 4G reduces hospital admissions and emergency department visits, reinforcing this strategy's efficacy and safety.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ARNI:

-

Dual inhibitors of type II angiotensin receptor and neprilysin

- BB:

-

Beta-blockers

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- CKD-EPI:

-

Chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration formula

- CRT:

-

Cardiac resynchronization therapy

- CV:

-

Cardiovascular

- GFR:

-

Glomerular filtration rate

- HF:

-

Heart failure

- HFrEF:

-

Heart failure with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction

- HFpEF:

-

Heart failure with a preserved left ventricular ejection fraction

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- ICD:

-

Implantd cardiac desfibrilator

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MRA:

-

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists

- NTproBNP:

-

Amino-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide type B portion

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RAASi:

-

Renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors

- SGLT2i:

-

Sodium and glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- TAPSE:

-

Tricuspid annulus plane systolic displacement

References

Conrad N, Judge A, Tran J et al (2018) Temporal trends and patterns in heart failure incidence: a population-based study of 4 million individuals. Lancet (London, England) 391:572–580

Martínez Santos P, Bover Freire R, Esteban Fernández A et al (2019) In-hospital mortality and readmissions for heart failure in Spain. A study of index episodes and 30-day and 1-year cardiac readmissions. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 72:998–1004

Gómez-Otero I, Ferrero-Gregori A, Varela Román A et al (2017) Mid-range ejection fraction does not permit risk stratification among patients hospitalized for heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 70:338–346

Anguita Gámez M, Esteban Fernández A, García Márquez M, del Prado N, Elola Somoza FJ, Anguita Sanchez M (2022) Age and stabilization of admissions for heart failure in Spain (2006–2019). The beginning of the end of the “epidemic”? Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 76(4):272–274

Savarese G, Lund LH (2017) Global public health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev 3:7

Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pocock SJ et al (2020) SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of the EMPEROR-reduced and DAPA-HF trials. Lancet (London, England) 396:819–829

McMurray JJV, Packer M, Desai AS et al (2014) Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 371:993–1004

Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, van Veldhuisen DJ et al (2022) A Systematic review and network meta-analysis of pharmacological treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JACC Heart Fail 10:73–84

Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D et al (2022) 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association joint committee on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 79:e263–e421

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M et al (2021) 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 42:3599–3726

Rosano GMC, Moura B, Metra M et al (2021) Patient profiling in heart failure for tailoring medical therapy. A consensus document of the heart failure association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 23:872–881

Anguita Sánchez M, Lambert Rodríguez JL, Bover Freire R et al (2016) Classification and quality standards of heart failure units: scientific consensus of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 69:940–950

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V et al (2015) Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging 16:233–271

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 147:573–577

McMurray JJV, Packer M (2021) How should we sequence the treatments for heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction?: a redefinition of evidence-based medicine. Circulation 143:875–877

Miller RJH, Howlett JG, Fine NM (2021) A novel approach to medical management of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Can J Cardiol 37:632–643

Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD et al (2019) Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med 380:539–548

Kapelios CJ, Laroche C, Crespo-Leiro MG et al (2020) Association between loop diuretic dose changes and outcomes in chronic heart failure: observations from the ESC-EORP heart failure long-term registry. Eur J Heart Fail 22:1424–1437

Beldhuis IE, Lam CSP, Testani JM et al (2022) Evidence-based medical therapy in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and chronic kidney disease. Circulation 145:693–712

Anker SD, Butler J, Filippatos G et al (2021) Effect of empagliflozin on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in patients with heart failure by baseline diabetes status: results from the EMPEROR-reduced trial. Circulation 143:337–349

Esteban-Fernández A, Ortiz Cortés C, López-Fernández S et al (2022) Experience with the potassium binder patiromer in hyperkalaemia management in heart failure patients in real life. ESC Hear Fail 9(5):3071–3078

Kotecha D, Holmes J, Krum H et al (2014) Efficacy of β blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. Lancet (London, England) 384:2235–2243

Böhm M, Swedberg K, Komajda M et al (2010) Heart rate as a risk factor in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): the association between heart rate and outcomes in a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England) 376:886–894

Tymińska A, Ozierański K, Wawrzacz M et al (2022) Heart rate control and its predictors in patients with heart failure and sinus rhythm. Data from the European Society of Cardiology long-term registry. Cardiol J. https://doi.org/10.5603/CJ.a2022.0076

Vardeny O, Claggett B, Kachadourian J et al (2018) Incidence, predictors, and outcomes associated with hypotensive episodes among heart failure patients receiving sacubitril/valsartan or enalapril: the PARADIGM-HF trial (prospective comparison of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor to determine impact on global mortality and morbidity in heart failure). Circ Heart Fail 11(4):e004745

Mebazaa A, Davison B, Chioncel O et al (2022) Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet (London, England). 400(10367):1938–1952

Oyanguren J, Garcia-Garrido L, Nebot-Margalef M et al (2021) Noninferiority of heart failure nurse titration versus heart failure cardiologist titration ETIFIC multicenter randomized trial. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 74:533–543

Crespo-Leiro MG, Segovia-Cubero J, González-Costello J et al (2015) Adherence to the ESC heart failure treatment guidelines in spain: ESC heart failure long-term registry. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 68:785–793

Acknowledgements

List of contributors to the TIDY-HF registry: Xabier Arana-Achaga, Francisco José Bermúdez Jiménez, Marta Cobo Marcos, Concepción Cruzado Álvarez, Juan F. Delgado Jiménez, Víctor Donoso Trenado, Inmaculada Fernández Rozas, Aleix Fort, Belén García, María Dolores García-Cosío Carmena, Clara Jiménez Rubio, Laura Jordán Martínez, Bernardo Lanza Reynolds, Juan Carlos López-Azor, Raquel López Vilella, Ainara Lozano Bahamonde, Irene Marco Clement, Elisabet Mena Sabastia, María Molina Villar, Julio Nuñez Villota, Pedro Agustín Pájaro Merino, Alejandro Pérez Cabeza, Montserrat Puga Martínez, Ainhoa Robles Mezcua, Ester Sánchez Corral, Enrique Sánchez Muñoz, José María Segura Aumente, Estefanía Torrecilla and Iñaki Villanueva Benito.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant for Heart Failure Research projects from the Heart Failure Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SECAINC-INV-ICC 21/003). An unconditional grant from Novartis and an unconditional grant from Boehringer-Ingelheim provided additional support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Study design: AE-F, IGO. Data collection: all authors. Data review and statistical analysis: AE-F, IGO. Manuscript drafting: AE-F, IGO. Review, editing, and acceptance of the manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

AE-F has received scientific speaking fees from Novartis, Bayer, Vifor, Fresenius, and Boehringer-Ingelheim. IGO has received funding or fees from Pfizer, Novartis, Rovi, Vifor, Orion, and Boheringer-Ingelheim. JJB reports consulting and speaking fees from Almirall, AstraZeneca, ArrhytNeT, Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo, Esteve, Impulse Dynamics, Orion Pharma, Novartis, Rovi, Servier, and Vifor. The other authors declare no conflict of interest with this article.

Additional information

The complete details of author involved in TIDY-HF investigators are given in acknowledgements.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Esteban-Fernández, A., Gómez-Otero, I., López-Fernández, S. et al. Influence of the medical treatment schedule in new diagnoses patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Clin Res Cardiol 113, 1171–1182 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-023-02241-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-023-02241-0