Abstract

Purpose

We describe an exceptional case of Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) that presented as Crohn’s disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Methods

The patient’s clinical, endoscopic, and histologic data from the Centre Hospitalier de l’Universite de Montreal were reviewed, as well as the literature on LCH involving the digestive tract and the liver, with a focus on the similarities with Crohn’s disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Results

A 39 years-old man first presented with anal fissures and deep punctiform colonic ulcers. Histologic assessment of colon biopsies showed chronic active colitis, consistent with Crohn’s disease. Mild cholestasis and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showing multiple intra and extrahepatic biliary tract strictures also led to a diagnosis of sclerosing cholangitis. Perianal disease progressed despite conventional treatment with antibiotics and infliximab. Subsequent discovery of non-Langerhans cutaneous xanthogranulomas and panhypopituitarism raised the suspicion of LCH, and a second review of colon biopsies ultimately led to the diagnosis, with the identification of Langerhans cells depicting elongated, irregular nuclei with nuclear grooves as well as immunohistochemical reactivity for S100, CD1a and vimentin. BRAF V600E mutation was detected afterwards by DNA sequencing of a bile duct sample.

Conclusion

LCH may mimic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and must be suspected in the presence of other suggestive clinical signs, or when there is failure of conventional IBD treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease is a frequent cause of inflammatory colitis worldwide. Classical histopathologic presentation is characterized by crypt distortion, chronic inflammation with or without basal plasmocytosis, transmural lymphoid aggregates, and non-necrotizing granulomas [1].

LCH is a neoplastic proliferation of myeloid dendritic cells. Histologic sections of LCH typically show aggregates composed of neoplastic dendritic cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, and lymphocytes; up to 57% of cases express the BRAF V600E mutation [2]. Gastrointestinal involvement usually presents with ulcerations and polyps, while hepatobiliary involvement has been described in rare cases [3, 4]. We hereby report a case of multisystemic LCH with digestive tract involvement that was initially misdiagnosed as Crohn’s disease.

Case report

A 39-year-old man first presented with severe anal fissures unresponsive to conventional treatment. The process had been ongoing for 9 months. No digestive symptoms were reported. A colonoscopy showed skip lesions throughout the colon with aphthous and deep ulcers of up to 1 cm in diameter and a submucosal fistula in the cecum (Fig. 1a, b). The terminal ileum was normal. Large anteroposterior anal fissures with indurated borders were observed. Crohn’s disease was suspected, and colon biopsies were sent for analysis with this information.

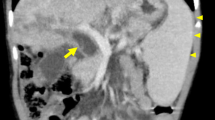

Endoscopic and histologic features of the affected colon. a Deep punctiform ulcers in the transverse colon. b Submucosal fistula in the cecum. c Photomicrograph depicting mild architectural distortion with predominantly mononuclear infiltrate in the lamina propria and reactive lymphoid follicles (HPS, × 10). d Zoomed-in view: large epithelioid cells suggestive of Langerhans cells intermixed with eosinophils (HPS, × 40). This was also seen in the bile duct aspiration. e CD1a staining of Langerhans cells (similar S100 and vimentin reactivity was also seen; not depicted; × 40). Cells were not expressing CD63 nor CD68 (not depicted). Immunohistochemistry marker: Ventana Medical System, Tucson, AZ; HPS hematoxylin-phloxine-safran

Upon initial histologic examination, mild architectural distortion and a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate were described. Crypt abscesses and hyperplastic lymphoid follicles were also observed. Sections of transverse and left colon biopsies showed large cell collections that were interpreted as granulomatas. Based on these observations, a diagnosis of granulomatous active chronic colitis was made. As part of the pre-immunosuppression assessment, both HIV and tuberculosis testing were negative.

Despite treatment with infliximab and antibiotics, anal fissures progressed to perianal wounds and multiple scrotal, ischiorectal, and inguinal abscesses requiring surgical drainage. Pre-immunosuppression workup revealed mild cholestasis, while subsequent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) showed multiple intra- and extrahepatic biliary tract strictures consistent with sclerosing cholangitis.

The patient’s previous records from another medical center were subsequently reviewed, which revealed a former diagnosis of panhypopituitarism with thickening of the pituitary stalk as seen using MRI. The panhypopituitarism first presented with insipidus diabetes and related workup showed central adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism, and hypogonadism. Moreover, a previous biopsy of cutaneous lesions showed xanthogranulomas consistent with non-X histiocytosis. The patient was referred to genetic (ZEH) and immunology services for evaluation since his multisystemic presentation raised the suspicion of LCH. Colon biopsies were then re-examined; an additional immunohistochemical study was performed. A revised diagnosis of colon involvement by LCH was made. Figure 1c–e depicts histologic findings from biopsies of the left colon, showing collection of large, epithelioid cells with irregular nuclei and central grooves, suggestive of Langerhans cells, intermixed with eosinophils. Langerhans cells expressed CD1a, S100, and vimentin. Of note, no BRAF V600E mutation was detected by DNA sequencing in the colon tissue sample.

A first liver biopsy performed using the transhepatic approach to rule out liver LCH was reviewed and only showed mild steatosis. However, the patient continued to suffer from cholestasis and intermittent cholangitis, requiring multiple ERCPs and transhepatic biliary drainages with lithotripsy for hepatolithiasis secondary to intra- and extrahepatic bile duct strictures. Aspirations of left and right hepatic ducts were performed during an ERCP, the content of which showed LCH cells expressing CD1a and S100 (Fig. 1d). The BRAF V600E mutation was detected by DNA sequencing of this bile duct sample. Finally, a PET scan revealed lytic bone lesions involving the skull and axial skeleton.

The patient was given a regimen of 5 days of cytarabine per month. His anal fissures healed progressively under chemotherapy, and general well-being improved. However, cholestasis and bile duct stenosis worsened. Prednisone 20 mg daily was introduced after seven chemotherapy cycles. After 3 months of treatment with corticosteroids, cholestasis improved with reduced intrahepatic bile duct dilatation and stenosis compared to baseline magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) imaging. Chemotherapy was completed after 11 cycles. Follow-up PET scan and colonoscopy showed disappearance of bone and colonic lesions; only the biliary tract involvement persisted. Second-line therapy with cladribine has been started and is well tolerated.

Discussion

We describe here a case of multisystemic LCH with digestive tract involvement, including the colon, anal area, and biliary tract. Gastrointestinal LCH is rare and mostly seen in the pediatric population. The adult form is usually less symptomatic, as shown in our patient’s case: his complaints were limited to pain due to anal fissures and right upper quadrant fullness. Indeed, in a series of 12 patients with LCH involving the gastrointestinal tract, 50% of the adult cases were found incidentally during colorectal cancer screening. The other 50% had non-specific symptoms [3]. In addition, anal and perianal presentations of LCH are rare; in a recent series, only 2 out of 85 cases showed anal disease, both with hepatobiliary involvement [4].

A complete review of the literature revealed four other cases of LCH that mimicked Crohn’s disease [5,6,7,8]. The main reasons for reconsidering the Crohn’s diagnosis were persistent colitis despite anti-TNF therapy in one patient with pulmonary histiocytosis, and stomach involvement with smooth fibrinous lesions in another [5, 7]. In a case series of patients with cutaneous histiocytosis, one adult was initially diagnosed and treated for Crohn’s disease with methylprednisolone. He also had biopsy-proven cirrhosis with sclerosing cholangitis-like features [6].

Colonic LCH may share some histologic similarities with Crohn’s disease. Both conditions can involve chronic changes such as crypt distortion, and lymphocytic and histiocytic infiltration of the mucosae. LCH collections of dendritic cells admixed with a fair amount of eosinophils may superficially resemble the granulomas of Crohn’s disease. Although Langerhans cells can mimic non-neoplastic histiocytes due to their abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, their elongated, irregular nuclei with nuclear grooves as well as immunohistochemical reactivity for S100, CD1a, vimentin, and BCL-2 are valuable in reaching the correct diagnosis [9].

Liver involvement is usually associated with multisystemic disease and carries a worse prognosis [4]. In a series of 23 patients, 56% presented with sclerosing cholangitis-like lesions, while the other 44% showed hepatomegaly, liver nodules, or isolated abnormal liver function tests (LFTs) [4]. Most liver involvement is limited to intrahepatic small- and medium-sized bile ducts. Early manifestations consist of inflammatory histiocytic infiltrates surrounding the bile ducts, leading to ductopenia and concentric fibrosis and stenosis [10]. However, histologic examination of the liver often shows non-specific findings due to late diagnosis or perhaps misguided sampling [4, 10]. In our case, sampling of medium- and large-sized bile ducts obtained with ERCP was successful in retrieving diagnostic material, a better approach compared to transhepatic biopsy. Finally, other cases of liver LCH have been reported to improve with corticosteroids, but cases with a sclerosing cholangitis-like presentation, as seen with our patient, may be harder to manage; liver transplantation is being proposed as a potential treatment for this presentation [4, 10].

BRAF V600E mutation was detected in the biliary tract specimen and not in the colonic tissue. This could be explained by the possible paucity (< 20%) of histiocytes in the colonic specimen, which could lead to false negative with conventional DNA sequencing [11]. There is very few data on BRAF V600E mutation among adult cases of LCH with digestive tract involvement. A French pediatric cohort showed an association between BRAF V600E mutation and multisystemic disease, liver and skin involvement, and permanent consequences (insipidus diabetes, sclerosing cholangitis), which are all featured in this adult case. Also, mutation carriers had a lower rate of response to first-line therapy, necessitating more often second-line or rescue therapy [11]. BRAF inhibitor (vemurafenib) has shown promising results in LCH [12]. However, response to this treatment in cases of digestive and biliary LCH remains to be established.

In conclusion, LCH is a multisystemic disease that rarely involves the gastrointestinal tract and may mimic Crohn’s disease or primary sclerosing cholangitis. Although the histologic features of LCH are typical, they may be difficult to recognize. Therefore, a high index of suspicion is necessary to attain the correct diagnosis in patients with multiorgan involvement.

References

Magro F, Langner C, Driessen A, Ensari A, Geboes K, Mantzaris GJ, Villanacci V, Becheanu G, Borralho Nunes P, Cathomas G, Fries W, Jouret-Mourin A, Mescoli C, de Petris G, Rubio CA, Shepherd NA, Vieth M, Eliakim R, European Society of P, European Cs, Colitis O (2013) European consensus on the histopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 7(10):827–851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crohns.2013.06.001

Berres ML, Allen CE, Merad M (2013) Pathological consequence of misguided dendritic cell differentiation in histiocytic diseases. Adv Immunol 120:127–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-417028-5.00005-3

Singhi AD, Montgomery EA (2011) Gastrointestinal tract Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a clinicopathologic study of 12 patients. Am J Surg Pathol 35(2):305–310. https://doi.org/10.1097/PAS.0b013e31820654e4

Abdallah M, Genereau T, Donadieu J, Emile JF, Chazouilleres O, Gaujoux-Viala C, Cabane J (2011) Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis of the liver in adults. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 35(6–7):475–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2011.03.012

Coronel E, Micic D, Rubin DT (2015) Patchy colitis and interstitial lung disease. Gastroenterology 148(1):26–27. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.003

Podjasek JO, Loftus CG, Smyrk TC, Wieland CN (2014) Adult-onset systemic Langerhans cell histiocytosis mimicking inflammatory bowel disease: the value of skin biopsy and review of cases of Langerhans cell histiocytosis with cutaneous involvement seen at the Mayo Clinic. Int J Dermatol 53(3):305–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05716.x

Roeb E, Etschmann B, Gattenlohner S (2012) Is it always Crohn’s disease in a patient with perianal fistulae and skip lesions in the colon? Gastroenterology 143(1):e7–e8. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.013

Sakanoue Y, Kusunoki M, Shoji Y, Yanagi H, Nishigami T, Yamamura T, Utsunomiya J (1992) Malignant histiocytosis of the intestine simulating Crohn’s disease. Report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 35(3):266–269

Behdad A, Owens SR (2014) Langerhans cell histiocytosis involving the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138(10):1350–1352. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2014-0290-CC

Desrame J, Bechade D, Defuentes G, Goasdoue P, Raynaud JJ, Claude V, Renard JL, Genereau T, Coutant G, Algayres JP (2005) Langerhans cell histiocytosis in an adult patient associated with sclerosing cholangitis and cerebellar atrophy. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 29(3):300–303

Heritier S, Emile JF, Barkaoui MA, Thomas C, Fraitag S, Boudjemaa S, Renaud F, Moreau A, Peuchmaur M, Chassagne-Clement C, Dijoud F, Rigau V, Moshous D, Lambilliotte A, Mazingue F, Kebaili K, Miron J, Jeziorski E, Plat G, Aladjidi N, Ferster A, Pacquement H, Galambrun C, Brugieres L, Leverger G, Mansuy L, Paillard C, Deville A, Armari-Alla C, Lutun A, Gillibert-Yvert M, Stephan JL, Cohen-Aubart F, Haroche J, Pellier I, Millot F, Lescoeur B, Gandemer V, Bodemer C, Lacave R, Helias-Rodzewicz Z, Taly V, Geissmann F, Donadieu J (2016) BRAF mutation correlates with high-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis and increased resistance to first-line therapy. J Clin Oncol 34(25):3023–3030. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9508

Heritier S, Jehanne M, Leverger G, Emile JF, Alvarez JC, Haroche J, Donadieu J (2015) Vemurafenib use in an infant for high-risk Langerhans cell histiocytosis. JAMA Oncol 1(6):836–838. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0736

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Maya Nader and Christina Tam for proofreading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Therrien A reviewed the medical record and scientific literature and wrote the manuscript. Nguyen B interpreted the histological specimens and supervised and reviewed critically the manuscript. Wartelle-Bladou C, Côté-Daigneault J, and El Haffaf Z contributed to the interpretation of data and reviewed critically the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Institutional review board statement

The publication of this case report was approved by the institutional review board, Le Comité d’éthique de la recherche du Centre Hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal.

Informed consent statement

The patient’s written consent was obtained for publication of this case report.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Therrien, A., El Haffaf, Z., Wartelle-Bladou, C. et al. Langerhans cell histiocytosis presenting as Crohn’s disease: a case report. Int J Colorectal Dis 33, 1501–1504 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3066-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-018-3066-y