Abstract

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of death from neoplastic disease in men and third in women of all ages. Globally, life expectancy is increasing, and consequently, an increasing number of operations are being performed on more elderly patients with the trend set to continue.

Elderly patients are more likely to have cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities that are associated with increased peri-operative risk. They further tend to present with more locally advanced disease, more likely to obstruct or have disseminated disease.

The aim of this review was to investigate the feasibility of laparoscopic colorectal resection in very elderly patients, and whether there are benefits over open surgery for colorectal cancer.

Methods

A systematic literature search was performed on Medline, Pubmed, Embase and Google Scholar. All comparative studies evaluating patients undergoing laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in the patients population over 85 were included.

The primary outcomes were 30-day mortality and 30-day overall morbidity. Secondary outcomes were operating time, time to oral diet, number of retrieved lymph nodes, blood loss and 5-year survival.

Results

The search provided 1507 citations. Sixty-nine articles were retrieved for full text analysis, and only six retrospective studies met the inclusion criteria. Overall mortality for elective laparoscopic resection was 2.92% and morbidity 23%. No single study showed a significant difference between laparoscopic and open surgery for morbidity or mortality, but pooled data analysis demonstrated reduced morbidity in the laparoscopic group (p = 0.032). Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery are more likely to have a shorter hospital stay and a shorter time to oral diet.

Conclusion

Elective laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer in the over 85 age group is feasible and safe and offers similar advantages over open surgery to those demonstrated in patients of younger ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of death from neoplastic disease in men and third in women of all ages [1,2,3] with a peak incidence between the 7th and 8th decades [4]. Globally, life expectancy has increased, and consequently, an increasing number of operations are being performed on more elderly patients with the trend set to continue.

Elderly patients are more likely to have cardiovascular and pulmonary comorbidities that are associated with increased peri-operative risk [5,6,7,8]. Further, advancing age leads to a reduced physiological reserve to cope with major surgery. In addition, elderly patients have been shown to present with more locally advanced disease, more likely to obstruct or have disseminated disease at time of presentation [9, 10]. Age is an independent risk factor for both morbidity and mortality when adjusted for other comorbidities [11].

Colorectal surgery has an increased risk of morbidity and mortality in the elderly population with a direct correlation between risk and age, i.e. the older patients having the highest risk [12]. The benefits of laparoscopic colorectal resections over open surgery have been clearly demonstrated in the general population [13,14,15], but there is limited knowledge for the elderly population. The haemodynamic changes secondary to an increased intra-abdominal pressure caused by the pneumoperitoneum can be associated with postoperative complications which may be most marked in this specific population [16].

The aim of this review was to investigate the feasibility of laparoscopic colorectal resection in very elderly patients, and whether there are benefits over open surgery for colorectal cancer.

Methods

Data sources and search strategy

Following the development of a review protocol in compliance with the PRISMA guidelines for reporting systematic reviews [17], two authors independently performed a comprehensive literature search of Medline, Pubmed, Embase and Google Scholar with no language, publication date or publication status restrictions. The searches were cross-checked against each other.

The search strategy included the terms in combination: “elective AND colorectal cancer AND laparoscopic surgery AND elderly”. The last search was run on September 30, 2015.

The reference list of the retrieved articles was searched to identify additional eligible studies.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) comparative studies evaluating patients undergoing laparoscopic versus open surgery for colorectal cancer in patient population over 85; (2) intention-to-treat analysis for the laparoscopic group (all procedures started laparoscopically were included in the laparoscopic group, even if converted); and (3) complete follow-up data on 30-day mortality and morbidity and losses to follow-up reported. Relevant studies with no control group were not included in the quantitative analysis, but data from large studies were collected on a separate spreadsheet.

Studies including only hand-assisted, robotic and single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) patients were excluded. Indexed abstract of posters and podium presentations at international meetings were not included. Reviews were only checked to find further relevant studies, and when the same author and institution published the same case series in different articles, only the most recent paper was evaluated.

Two reviewers independently assessed the reports for eligibility at title and abstract level. In case of discrepancies, a third author was consulted, and agreement was reached by consensus.

Data extraction, methodological quality appraisal and risk of bias assessment

Two authors independently retrieved the data from each included study filling an electronic database. For studies that reported insufficient data, the authors were contacted for further information; if no response was obtained after two reminders, the study was excluded from the review.

The quality of the included studies was evaluated by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [18]: on a scale of 9, a greater score was considered to be an indicator of better quality.

Outcome analysis

The primary outcomes were 30-day mortality and 30-day overall morbidity. Secondary outcomes were operating time, time to oral diet, number of retrieved lymph nodes, blood loss and 5-year survival.

Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used as summary measures for dichotomous outcomes, while weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CI were used for continuous outcomes.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 12 statistical software (STATA Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Study selection

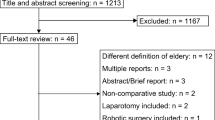

The search provided 1507 citations. After exclusion of 1438 not relevant articles at title and abstract level, 69 full text articles were assessed for eligibility and 6 studies met the inclusions criteria. A flowchart of the article yield is shown in Fig. 1. No unpublished relevant studies were found.

All the included studies were retrospective. Five were single centre studies [4, 19,20,21,22], one was multicenter [11], three compared laparoscopic to open resection in the over 85 age group [19, 20, 22] and two studies compared all colorectal resections between over and under 85 age groups [4, 11]. One study compared laparoscopic to open resections against multiple age groups [21]. The variables are displayed in Table 1.

Laparoscopic versus open

Patient demographics

Three studies reported no differences in the ASA grade between the two groups, while the fourth study did not report ASA grade. However, no differences were demonstrated in comorbidities such as heart failure and diabetes (p = 0.672). The most common cardiovascular diseases were hypertension and ischaemic heart failure [4] with a trend towards increased frequency of chronic pulmonary disease in the elderly group [11]. In three studies, the open and laparoscopic groups were comparable for tumour stage, while one study reported a significant difference, with less stage II and stage III patients in the laparoscopic group (p = 0.009). Two studies reported that the dimensions of the tumour were significantly larger in the open groups (p = 0.02 and p = 0.0371).

Primary outcomes

None of the studies demonstrated a significant difference in 30-day morbidity between the open and laparoscopic group. However, pooled data analysis demonstrated a significant benefit for laparoscopic surgery (31/135 for the laparoscopic group versus 54/157 for the open group, p = 0.032).

No difference was demonstrated in mortality. This was confirmed also at pooled data analysis (4/137 for the laparoscopic groups, 7/169 for the open groups, p = 0.568). The study results are shown in Table 2 with pooled data and analysis displayed in Table 3 .

Length of hospital stay, time to oral diet and postoperative analgesia

All four studies [19,20,21,22] reported length of hospital stay, two found no difference between the groups and the other two found significantly shorter hospital stay in the laparoscopic group (p < 0.001, p = 0.0001) [20, 22]. The mean length of stay varied between 10 and 20.2 days for laparoscopic and 15.4–21.7 for open. Pooled data showed an overall average stay of 13.1 and 18.9 days in the laparoscopic and open group, respectively (p < 0.0001).

Two studies reported a significantly shorter time to oral diet in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery (means of 3.4 versus 4.2 days, p = 0.03 and 2.7 versus 7.7 days, p < 0.0001) [19, 20], while only one study assessed the use of postoperative analgesia showing a significantly reduced demand in the laparoscopic group (p = 0.01) [19].

Operating time and blood loss

Of the three studies that measured length of operation, all three found that laparoscopic surgery had statistically significantly longer operative times (p < 0.01, p = 0.014, p = 0.0017) [19, 20, 22].

Intraoperative blood loss was less in the laparoscopic group in two studies (p < 0.001, p < 0.0001) [20, 22], while the third study demonstrated no differences.

Number of retrieved lymph nodes and 5-year survival

Lymph node dissection was measured in three of the studies with varying results. One study found that significantly fewer lymph nodes were retrieved in the laparoscopic group (means of 11.4 versus 18.2, p = 0.0181) [22], and the other two studies found that significantly more nodes were retrieved (p < 0.01, p = 0.032) [19, 20].

Two studies reported 5-year survival demonstrating no difference in the two study populations.

Morbidity and mortality in the over 85 patient population

Two studies compared morbidity and mortality for laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection in patients under the age of 85 and patients over the age of 85 [11, 21].

Pooled data analysis showed that the overall complication rate for all patients under 85 years old was 31.2% (142/455), and for the over 85 was 35.6% (32/90), (p = 0.419). Mortality in the under 85 age group was 4.2% (19/455) and 8.9% (8/90), (p = 0.0597) in the over 85.

Stepien et al. [4] compared a group of 94 patients over the age of 85 (mean = 88.9) with a random selection of 91 patients between the ages of 45–75 (mean = 56.4). They found that the older group presented with significantly more comorbidities (p < 0.01) and had a higher rate of emergency presentation (63–34.1%). However, this was for all surgical treatments and not specifically colorectal cancer. The study also showed a significant increase in rates of mortality in the older group (p < 0.05), but only for emergency admissions and not elective resection. Rates of overall complications for both emergency and elective admissions were found to be significantly different between the two groups (p < 0.01). The study was unable to demonstrate any difference in length of hospital stay between the groups with a mean stay of 10.7 days in the older group versus 9.4 days in the control (p > 0.05).

Jafadi et al. [11] demonstrated a higher rate of comorbidity in the over 85 age group using the “Elixhauser-Van Walraven comorbidity score” [23], with the over 85 group demonstrating a mean score of 9 (SD 3). The study also showed that the over 85 group had a higher rate of emergency admission at 50.4% as compared to the other age groups (45–64 = 29%, 65–69 = 29.6%, 70–74 = 31%, 75–79 = 34%, 80–84 = 39%).

Similarly, this study found a significant increase in mortality rates (p < 0.01) when compared to the control group of 45–64 years old. The study then calculated the risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality with an odds ratio of 4.7 and confidence intervals (CI) 4.30–5.18. Interestingly, the authors also found that over the 10-year observation period, the overall rates of mortality fell by an average of 6.6% per year with the over 85 age group having the highest rate of decreasing mortality at 9.1%.

The study also demonstrated a significant difference in mortality between the over 85 and the control age groups (p < 0.01), and the risk-adjusted morbidity was calculated with the odds ratio of 1.96 (CI 1.89–2.03). Specific complication was also assessed, and no difference in anastomotic leak, intra-abdominal abscess, intestinal fistula and ileus were demonstrated. However, other complications such as acute renal failure, cardiac complications, respiratory failure, urinary tract infection and pneumonia were more commonly present in the over 85 group (p < 0.01). Finally, the study acknowledges that the over 85 age group had the longest mean length of hospital stay at 12 days versus the control group at 9 days (p < 0.05).

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that laparoscopic surgery is a feasible and safe alternative to open surgery in the very elderly, with no reported differences in clinical outcomes between the two approaches. However, there are no prospective randomized studies that have reported on this topic to date. Although there is limited information available regarding the most elderly groups of cancer resection, a trend towards reduced length of hospital stay, shorter time to oral diet and reduced 30-day morbidity has been demonstrated in our study. The reduced use of opiates and the early return of bowel functions can also translate in early return to independence in this group of patients. This reflects current data of laparoscopic versus open surgery across all age groups even in high risk patients [24].

These conclusions need to be confirmed in larger trials specific to this population with consideration to non-operative treatment options in addition to the proportion of patients who present acutely and the permanent colostomy rates.

No significant difference in mortality has been demonstrated in laparoscopic versus open surgery in this patient population. Age in itself is an independent risk factor for mortality, although our study demonstrates a significant decrease in mortality over the past decade [11]. This most likely reflects overall improvements and advances in healthcare as well as more experience in the multidisciplinary management of an increasing ageing population [25]. These findings confirm the need for highly trained laparoscopic surgeons and experienced anaesthetists with interest in colorectal surgery as the length of surgery and late conversion directly relate to complications.

Our study has some limitations. The included studies have collected data over an extensive period of time that spans the introduction of laparoscopic colorectal resections. This means there would have been a learning curve for laparoscopy in the earlier studies adding some degree of bias to the results.

It is important to note that the heterogeneity of the included studies is another limitation that might have affected the significance of the pooled data analysis. In fact, variability exists amongst surgeons on the rate of defunctioning ileostomy, and surprisingly, data on preoperative radiochemotherapy are often lacking. This highlights the need for comprehensive prospective randomized trials.

Moreover, a tendency towards including more selected cases in the laparoscopic group was noted with larger tumours more likely to be resected via open surgery. However, as surgical experience and confidence grow, more difficult resections will be attempted laparoscopically [26]. These operative outcomes will also improve with regard to length of operation and rate of conversion [27,28,29].

As for the feasibility of surgery on the very old, there is compelling evidence that we have yet to find an upper limit of age where elective resection becomes a non-viable option. Although age has been demonstrated as an independent risk factor for mortality separate from comorbidity, this is across both elective and emergency admissions for open and laparoscopic surgery and is found to be 8% [11]. Not only is this set to improve based on the current trends but with regard to the laparoscopic studies examined the rates of mortality ranged from only 0–6.7%. It is important to have a robust preoperative assessment to ensure that patient risk stratification can be accurately detailed and the risks of surgery discussed. Appropriate patient selection is even more important in achieving favourable clinical outcomes for this unique sub-group and involves a multidisciplinary approach between surgeons, anaesthetists and nursing colleagues. Preoperative investigations and peri-operative planning with the use of high dependency and intensive care facilities are key to success.

Conclusion

Elective laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer in the over 85 age group is feasible and safe and offers similar advantages over open surgery to those demonstrated in patients of younger ages. This study demonstrates that advanced age must not be considered a contraindication to the laparoscopic approach.

References

Malvezzi M, Arfe A, Bertuccio P et al (2011) European cancer mortality predictors for the year 2011. Ann Oncol 22:947–956

Rossi T, Malvezzi M, Bosetti C et al (2016) Cancer mortality in Europe, 1970–2009: an age, period and cohort anaysis. Eur J Cancer Prev. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000282

Yamauchi M, Lochhead P, Morikawa T et al (2012) Colorectal cancer: a tale of two sides or a continuum? Gut 61:794–797

Stepien S, Gluszek S, Koziel D et al (2014) The risk of surgical treatment in patients aged 85+, with special consideration of colorectal cancer. Pol Prezegl Chir 86(3):132–140

Merlin F, Prochilo T, Tondulli L et al (2008) Colorectal cancer treatment in elderly patients: an update on recent clinical studies. Clin Colorectal Cancer 7:357–363

Akiyoshi T, Kuroyanagi H, Oya M et al (2009) Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic rectal surgery for primary rectal cancer in elderly patients: is it safe and beneficial? J Gastrointest Surg 13:1614–1618

Amemiya T, Oda K, Ando M et al (2007) Activities of daily living and quality of life of elderly patients after elective surgery for gastric and colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 246:222–228

Ganai S, Lee KF, Merrill A et al (2007) Adverse outcomes of geriatric patients undergoing abdominal surgery who are at high risk for delirium. Arch Surg 142:1072–1078

Scott NA, Jeacock J, Kingston RD (1995) Risk factors in patients presenting as an emergency with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 82:321–323

Turrentine FE, Wang H, Simpson V et al (2007) Surgical risk factors, morbidity and mortality in elderly patients. J Am Coll Surg 203:865–877

Jafari MD, Hafari F, Halabi WJ et al (2014) Colorectal cancer resections in the aging US population: a trend toward decreasing rates and improved outcomes. JAMA Surg 149:557–564

Longo WE, Virgo KS, Johnson FE et al (2000) Risk factors for morbidity and mortality after colectomy for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 43:4383–4391

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H et al (2005) Short term end points of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365:1718–1726

Neudecker J, Klein F, Bittner R et al (2009) Short-term outcomes from a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 96:1458–1467

Takahata O, Kunisawa T, Nagashima M et al (2007) Effect of age on pulmonary gas exchange during laparoscopy in the Trenedelenburg lithotomy position. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 51:687–692

Van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA et al (2013) Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 14:210–218

Moher D, Liberati A, Telzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 339:b2535

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’Amico R, International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group, European Carotid Surgery Trial Collaborative Group et al (2003) Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess 7(27):iii-x):1–173

Tominaga T, Takeshita H, Arai J et al (2015) Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in oldest-old patients. Dig Surg 32:32–38

Mukai T, Akiyoshi T, Ueno M et al (2014) Outcomes of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer in oldest-old patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 24:366–369

Vallribera Valls F, Landi F, Espin Basany E et al (2014) Laparoscopy-assisted versus open colectomy for treatment of colon cancer in the elderly: morbidity and mortality outcomes in 545 patients. Surg Endosc 28:3373–3378

Nakamura T, Sato T, Miura H et al (2014) Feasibility and outcomes of surgical therapy in very elderly patients with colorectal cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 24:85–88

van Walraven C, Austin PC, Jennings A et al (2009) A modification of the Elixhauser comorbidity measures into a point system for hospital death using administrative data. Med Care 47:626–633

Hernandas AK, Abdelrahman T, Flashman KG et al (2010) Laparoscopic colorectal surgery produces better outcomes for high risk cancer patients compared to open surgery. Ann Surg 252:84–89

Harari D, Hopper A, Dhesi J et al (2007) Proactive care of older people undergoing surgery (‘POPS’): designing, embedding, evaluating and funding a comprehensive geriatric assessment service for older elective surgical patients. Age Ageing 36(2):190–196

Marush F, Gastinger I, Schneider C et al (2001) Experience as a factor influencing the indications for laparoscopic colorectal surgery and the results. Surg Endosc 15:116–120

Giglio MC, Celentano V, Tarquini R et al (2015) Conversion during laparoscopic colorectal resections: a complication or a drawback? A systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcomes. Int J Color Dis 30(11):1445–1455

Tekkis PP, Senagore A, Delaney et al (2005) Evaluation for the learning curve in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: comparison of right-sided and left-sided resections. Ann Surg 242:83–91

Mackenzie H, Miksovic D, Ni M et al (2013) Clinical and educational proficiency gain of supervised laparoscopic colorectal surgical trainees. Surg Endosc 27:2704–2711

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Devoto, L., Celentano, V., Cohen, R. et al. Colorectal cancer surgery in the very elderly patient: a systematic review of laparoscopic versus open colorectal resection. Int J Colorectal Dis 32, 1237–1242 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2848-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00384-017-2848-y