Abstract

A 10-year-old, male patient with a head injury caused by a fall presented with chemosis, exophthalmos, right orbital bruit, and intracranial venous reflux, based on which posttraumatic carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) was diagnosed. Coil embolization was semi-urgently performed for the dangerous venous drainage. After the treatment, right abducens nerve palsy newly appeared. To treat the neurological symptoms and preserve the parent artery, curative endovascular treatment using a pipeline embolization device (PED) with coil embolization was performed after starting dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT). The CCF and abducens nerve palsy finally resolved, and the internal carotid artery (ICA) was remodeled. Use of the PED with adjunctive coil embolization was effective and safe in the present case of pediatric traumatic direct CCF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Posttraumatic carotid cavernous fistula (CCF) usually presents high-flow shunt via direct fistulas between the internal carotid artery (ICA) and cavernous sinus. Symptoms include chemosis, exophthalmos, orbital bruit, pulsating tinnitus, vision loss, oculomotor or abducens nerve palsy, headache, and, occasionally, convulsions or intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) [1,2,3]. The ideal treatment involves occluding the arteriovenous shunt while maintaining ICA patency [4]. Detachable coils, n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate, and Onyx are normally used in the standard treatment. However, numerous studies have recently examined the use of flow diverter stents in CCF treatment [1, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] although most of the patients were adults or adolescents. We herein reported a pediatric case of traumatic direct CCF successfully treated using a flow diverter stent with detachable coils.

Case presentation

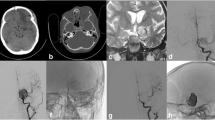

The patient was a 10-year-old male who fell from a height of two meters. He presented with bruising of the right eye and vision loss (0.02). Head CT revealed right orbital fractures (Fig. 1A). On day 28, chemosis and exophthalmos of the right eye (Fig. 1B) and pulsatile bruit were observed. Ophthalmological examination revealed temporal hemianopia and visual loss (0.15) in the right eye. Brain MRI showed engorgement of the right superior orbital vein and superficial middle cerebral veins. Based on these findings, posttraumatic direct CCF was diagnosed. To ameliorate the symptoms, semi-emergent endovascular treatment was performed. A right internal carotid angiogram performed under general anesthesia revealed the direct CCF between the right ICA and cavernous sinus, venous reflux into the right superior orbital vein, superficial middle cerebral veins, and uncal vein, and poor opacification of the right middle cerebral artery (MCA) and anterior cerebral artery (ACA) (Fig. 2A). A left internal carotid angiogram revealed opacification of the right ACA and MCA via the anterior communicating artery. Under systemic heparinization, a 5-Fr guiding sheath and 3.4-Fr intermediate catheter were advanced into the right internal jugular vein and the cavernous sinus, respectively. The microcatheter was advanced into the uncal vein, superior orbital vein, and superficial middle cerebral veins, then, transvenous embolization (TVE) with coils was performed. The post-treatment angiogram showed resolution of the venous reflux (Fig. 2C). Postoperatively, the chemosis and exophthalmos improved, but on postoperative day 3, right abducens nerve palsy appeared (Fig. 1C). To treat the neurological symptoms and preserve the ICA, curative endovascular treatment using a pipeline embolization device (PED) with TAE was scheduled for postoperative day 21. The patient was pretreated with dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of aspirin (81 mg/day) and clopidogrel (37.5 mg/day). Under general anesthesia, a triaxial system, including a microwire, microcatheter, and 5-Fr intermediate catheter, was navigated into the proximal region of the CCF. A 4 × 18-mm PED (Pipeline shield, Medtronic, Ireland) was navigated distal to the posterior communicating artery and deployed to cover the CCF (Fig. 2D). Subsequently, an adjunctive TAE was performed with coils using the jailing technique (Fig. 2F). Since the TAE failed to occlude the fistula, and natural thrombosis had not occurred, TVE with coils was performed in the next session six weeks after the second treatment. The final angiogram revealed almost complete disappearance of the shunt flow and restoration of the antegrade ICA flow (Fig. 2G). By postoperative day 14, the right abducens nerve palsy had completely resolved (Fig. 1D). However, visual acuity in the right eye returned only to 0.20, and the temporal hemianopia remained. Four months later, a cerebral angiogram visualized complete occlusion of the CCF and ICA remodeling (Fig. 2H). DAPT was then terminated. The patient was followed up for ten months but experienced no recurrence.

Head CT at the first visit (A) and photographs of eye positions at diagnosis (B) 3 days after the first treatment (C) and 2 weeks after final treatment (D). The head CT revealed lateral right orbital bone fractures (arrow) (A). Chemosis and exophthalmos of the right eye were observed at posttraumatic CCF diagnosis (B). Although the chemosis and exophthalmos improved, right abducens nerve palsy appeared 3 days after the first TVE for the venous drainage (C). The right abducens nerve palsy resolved after the last treatment (D)

Right internal carotid angiograms. Lateral view (A) and 3-dimensional rotational image (B) of preoperative internal carotid angiogram revealed the direct CCF, venous reflux into the right superior orbital vein (arrow head), superficial middle cerebral veins (arrow), and uncal vein (small arrow), and the shunt point (circle). Lateral view of the internal carotid angiogram after the first treatment demonstrated resolution of the venous reflux (C). PED placement across the fistula can be seen (D). Deployment of PED with adjunctive TAE using coils was performed, resulting in incomplete fistula occlusion (E). Lateral view of the right internal carotid angiogram before (F) and after (G) the third treatment demonstrated nearly complete resolution of the shunt (arrow). Four months later, the CCF was completely occluded (H)

Discussion

Three sessions of endovascular treatment were performed in this case. These staged therapies ensured that the dose of contrast medium per session could be kept to a minimum, DAPT could be safely started without dangerous venous reflux, and neurological symptoms could be improved prior to radical treatment. Unexpectedly, the right abducens nerve palsy appeared after the first session, possibly due to increased pressure in the cavernous sinus after the drainage of the CCF decreased. The right abducens nerve palsy resolved completely in two weeks after the final treatment. In contrast, limited improvement was observed in the vision of the right eye, apparently due to the initial, traumatic damage to the optic nerve.

Several case series have reported the safety and efficacy of flow diverter stents [1, 4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. However, most of the patients enrolled in these studies were adults or adolescents [1, 4, 11]. We reviewed the literature on posttraumatic CCF in pediatric patients aged 10 years or younger (Table 1) and found that Barburoglu et al. reported two pediatric cases of CCF treated with flow diverter stents but gave no details about their age [1]. Only seven traumatic CCF cases in patients aged 10 years or younger who were treated with other methods have been reported [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Treatment is generally required for posttraumatic CCF. However, packing too many coils into the cavernous sinus may increase the internal pressure, exacerbating the neurological symptoms [19]. Parent artery occlusion may be required if the fistula cannot be occluded by other means. Hemodynamic stress caused by non-physiological conditions may increase the risk of de-novo aneurysm formation later [20]. Sacrificing the parent artery should be considered carefully in children.

Progress in flow diverter stent technology has significantly impacted the treatment of direct CCF by allowing (1) preservation of the parent artery during fistula occlusion; (2) reduction in the amount of coil used with multiple flow diverter stents; and (3) thrombosis induction even in the presence of residual shunt flow after treatment. These effects can reduce the stenosis and thrombosis risk in the parent artery and prevent neurological complications [4]. Flow diverter stents may be used as a scaffold and treated with coils or liquid embolic substances [4, 5]. In stand-alone treatments, multiple stents will usually be required to occlude the fistula completely [5].

Flow diverter stents have come to be used commonly for most cases of CCF in recent years. However, the indications for its use should be carefully considered especially in children because long-term follow-up is required, and the cost may be high in many countries.

Conclusion

Deployment of PED with adjunctive coil embolization for pediatric direct CCF was effective in occluding the fistula while reducing the total amount of coil placed in the cavernous sinus and preserving the parent artery.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CCF:

-

Carotid cavernous fistula

- ICA:

-

Internal carotid artery

- ICH:

-

Intracerebral hemorrhage

- MCA:

-

Middle cerebral artery

- ACA:

-

Anterior cerebral artery

- TVE:

-

Transvenous embolization

- TAE:

-

Transarterial embolization

- PED:

-

Pipeline embolization device

- DAPT:

-

Dual antiplatelet therapy

References

Barburoglu M, Arat A (2017) Flow diverters in the treatment of pediatric cerebrovascular diseases. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 38:113–118

Henderson AD, Miller NR (2018) Carotid-cavernous fistula: current concepts in aetiology, investigation, and management. Eye (Lond) 32:164–172

Naragum V, Barest G, AbdalKader M, Cronk KM, Nguyen TN (2018) Spontaneous resolution of post-traumatic direct carotid-cavernous fistula. Interv Neurol 7:1–5

Baranoski JF, Ducruet AF, Przbylowski CJ, Almefty RO, Ding D, Catapano JS, Brigeman S, Fredrickson VL, Cavalcanti DD, Albuquerque FC (2019) Flow diverters as a scaffold for treating direct carotid cavernous fistulas. J Neurointerv Surg 11:1129–1134

Huseyinoglu Z, Oppong MD, Griffin AS, Hauck E (2019) Treatment of direct carotid-cavernous fistulas with flow diversion - does it work? Interv Neuroradiol 25:135–138

Limbucci N, Leone G, Renieri L, Nappini S, Cagnazzo F, Laiso A, Muto M, Mangiafico S (2020) Expanding indications for flow diverters: distal aneurysms, bifurcation aneurysms, small aneurysms, previously coiled aneurysms and clipped aneurysms, and carotid cavernous fistulas. Neurosurgery 86:S85–S94

Lin LM, Colby GP, Jiang B, Pero G, Boccardi E, Coon AL (2015) Transvenous approach for the treatment of direct carotid cavernous fistula following Pipeline embolization of cavernous carotid aneurysm: a report of two cases and review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg 7:e30

Nadarajah M, Power M, Barry B, Wenderoth J (2012) Treatment of a traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula by the sole use of a flow diverting stent. J Neurointerv Surg 4:e1

Ogilvy CS, Motiei-Langroudi R, Ghorbani M, Griessenauer CJ, Alturki AY, Thomas AJ (2017) Flow diverters as useful adjunct to traditional endovascular techniques in treatment of direct carotid-cavernous fistulas. World Neurosurg 105:812–817

Pradeep N, Nottingham R, Kam A, Gandhi D, Razack N (2015) Treatment of post-traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas using pipeline embolization device assistance. BMJ Case Rep 2015

Wendl CM, Henkes H, Martinez Moreno R, Ganslandt O, Bäzner H, Aguilar Pérez M (2017) Direct carotid cavernous sinus fistulae: vessel reconstruction using flow-diverting implants. Clin Neuroradiol 27:493–501

Barrow DL, Fleischer AS, Hoffman JC (1982) Complications of detachable balloon catheter technique in the treatment of traumatic intracranial arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurosurg 56:396–403

Debrun G, Lacour P, Vinuela F, Fox A, Drake CG, Caron JP (1981) Treatment of 54 traumatic carotid-cavernous fistulas. J Neurosurg 55:678–692

Morais BA, Yamaki VN, Caldas J, Paiva WS, Matushita H, Teixeira MJ (2018) Post-traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula in a pediatric patient: a case-based literature review. Childs Nerv Syst 34:577–580

Paiva WS, de Andrade AF, Beer-Furlan A, Neville IS, Noleto GS, Bernardo LS, Caldas JG, Teixeira MJ (2013) Traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula at the anterior ascending segment of the internal carotid artery in a pediatric patient. Childs Nerv Syst 29:2287–2290

Pawar N, Ramakrishanan R, Maheshwari D, Ravindran M (2013) Acute abducens nerve palsy as a presenting feature in carotid-cavernous fistula in a 6-year-old girl. GMS Ophthalmol Cases 3:Doc03

Wajima D, Nakagawa I, Park HS, Yokoyama S, Wada T, Kichikawa K, Nakase H (2017) Successful coil embolization of pediatric carotid cavernous fistula due to ruptured posttraumatic giant internal carotid artery aneurysm. World Neurosurg 98:871.e823-871.e828

Yang Y, Kapasi M, Abdeen N, Dos Santos MP, O’Connor MD (2015) Traumatic carotid cavernous fistula in a pediatric patient. Can J Ophthalmol 50:318–321

Bink A, Goller K, Luchtenberg M, Neumann-Haefelin T, Dutzmann S, Zanella F, Berkefeld J, du Mesnil de Rochemont R (2010) Long-term outcome after coil embolization of cavernous sinus arteriovenous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31:1216–1221

Arambepola PK, McEvoy SD, Bulsara KR (2010) De novo aneurysm formation after carotid artery occlusion for cerebral aneurysms. Skull Base 20:405–408

Acknowledgements

All the authors would like to thank Mr. James Robert Valera for his assistance with editing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Kyoji Tsuda wrote the first draft. Takahiro Ota, Maya Kono, and Satoshi Ihara reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

The patient and his parents consented to the submission of this case report to the journal. Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest regarding the content of this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper has not been previously published or presented

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tsuda, K., Ota, T., Kono, M. et al. Flow diverter stents for pediatric traumatic carotid cavernous fistula: a case report and literature review. Childs Nerv Syst 38, 1409–1413 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-021-05423-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-021-05423-1