Abstract

Ventriculo-femoral vein shunts have been described in few case reports as an alternative for treating complex cases of hydrocephalus in which other accesses are discarded. To our best knowledge, only 6 cases have been reported in the literature to date. We present a case of a 2-year-old female patient with hydrocephalus secondary to neonatal sepsis and meningitis. Patient was operated with various types of shunting procedures, such as ventriculo-peritoneal (V-P) shunt, ventriculo-atrial (V-A) shunt, ventriculo-pleural (V-PL) shunt, ventriculo-vesical shunt, ventriculo-superior sagittal sinus (V-SSS) shunt, and ventriculo-caval (V-C) shunt. All previous procedures were unsuccessful in treating the hydrocephalus. Finally, right ventriculo-femoro-caval shunt procedure was performed. Distal catheter was inserted into the right femoral vein and passed toward inferior vena cava under fluoroscopy guidance. The early postoperative period was uneventful. Late postoperative complications consisting of few periods of shunt dysfunction and distal obstruction were managed as an outpatient with injection for diluted heparin in the shunt valve, resulting in recovery of the shunt function. This was the management until the age of 4 when the femoral vein shunt was removed and right ventriculo-pleural shunt was placed. The patient tolerated this surgery and long-term follow-up showed good neurological status without episodes of shunt dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A variety of modalities exists for the management of hydrocephalus. Ventriculo-peritoneal (V-P), ventriculo-atrial (V-A) and ventriculo-pleural (V-PL) shunts are the most widely used methods for this indication [1]. For more rare situations, ventriculo-superior sagittal sinus (V-SSS), ventriculo-caval (V-C), ventriculo-vesicular (V-V), and ventriculo-biliary shunts are reported to be used for draining CSF in selected patients when conventional sites are not suitable either due to adhesions, infection, thrombosis, or obliteration [1]. In this article, the authors present a case of ventriculo-femoro-caval (V-F-C) shunt. To our best knowledge, only 6 cases have been reported in the literature to date [2,3,4].

Case presentation

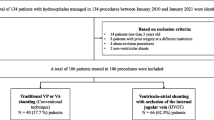

A preterm female baby was born at 34 weeks of pregnancy and transferred to the neonatal unit and developed neonatal sepsis and secondary bacterial meningitis, which resulted in communicating hydrocephalus. Patient was operated with ventriculo-peritoneal (V-P) shunt, which was failed and resulted in abdomen collection. The patient was then operated with V-A shunt. After 7 mounts and at the patient’s age of 13 months, the V-A shunt was removed due shunt infection. After that, the patient underwent many surgical procedures which all failed. Two V-P shunt operations were performed and failed due to intra-abdominal CSF collection. Also, 2 ventriculo-pleural (V-PL) shunt operations were performed and failed due to pleural effusion. Ventriculo-subclavian vein shunt operation was performed by percutaneous puncturing of the subclavian vein. Shunt failure developed due to breaking of the distal catheter at the subclavian vein entry site and migration to the right atrium of the heart. The migrated part was removed from heart with endovascular technique. Two ventriculo-vesical (V-V) shunt operations were performed and was complicated with E. coli meningitis and treated with antibiotics and EVD. V-A shunt was performed into the left internal jugular vein and failed due to stenotic jugular veins and left in place. The patient was transferred to our center with the EVD and she was at the age of 2 years. At the age of 2 year old, the patient was operated with ventriculo-superior sagittal sinus (V-SSS) shunt. Shunt failure developed after 1 month of surgery due to diagnosed the stenosis of both internal jugular veins in the CT venography. Decision was made to perform ventriculo-femoro-caval (V-F-C) shunt. Under general anesthesia and supine position, right inguinal area was dissected and right femoral vein was exposed. Distal catheter was inserted inside the vein upward toward the heart through the IVC guided by intraoperative C-arm fluoroscopy until reaching proximal to hepatic segment of the IVC (Fig. 1). Catheter and field irrigation was performed with diluted heparin (heparin 1 IU /1 cc normal saline). We made a small subcutaneous pocket around the site of the incision to harbor the smooth loop of the distal catheter preventing the sharp upward bending of the catheter at the venous insertion site. We intentionally left a long segment of the distal catheter inside the venous system as we did not know how long the shunt is going to remain in the patient, thus, tolerating possible body growth. Also, we preferred that the CSF is to be emptied directly in a large and high flow vein to avoid possible venous occlusion and/or thrombosis. The operation and postoperative period were uneventful. Postoperative low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) prophylactic dose of 0.5 mg/kg given subcutaneously twice a day was established. Patient was discharged after 1 week of the operation on anticoagulants with total recovery of symptoms. The patient was followed up until the age of 4 years. During this follow-up, the patient was referred to our emergency room 4 times—with mean interval of 6 months—with signs of shunt distal dysfunction. This was managed in the ER with injection of 20 cc of heparin diluted with normal saline (heparin 1 IU/1 cc NS) into the valve. The shunt resumed functioning after injection 3 times. In the last obstruction, management with percutaneous heparin injection failed. The patient was admitted and femoral vein shunt was removed and the tip of the shunt was found obstructed with coagulum. In the same operation, right V-PL shunt was placed. The operation and the postoperative period were uneventful. Patient is still under follow-up since 1 year of the operation and showing good neurologic status and functioning shunt.

a Schematic drawing showing the insertion point of the lower catheter into the femoral vein and the tract of the lower catheter toward the inferior vena cava. b P-A chest-abdomen-pelvis x-ray showing the final position of the distal catheter’s tip in the IVC through the femoral vein. IVC inferior vena cava, HV hepatic vein (segment), AVC abdominal vena cava, IIV internal iliac vein, EIV external iliac vein, FV femoral vein

Discussion

Once a diagnosis of hydrocephalus is made in a child, surgical treatment is mandated. The indication for treatment of pediatric hydrocephalus is ventriculomegaly associated with signs and symptoms of raised ICP [1]. V-P shunts remains the procedure of choice for hydrocephalus, due to the advantages of this procedure including technical simplicity, high efficacy, lower rate, and lesser severity of complications [1]. A variety of complex abdominal conditions, such as adhesions, prior major abdominal surgery, history of peritonitis, ascites, peritoneal dialysis, and failure of prior V-P shunt, makes the surgeons look for other alternatives for the shunt placement [1]. Such alternatives include V-A shunt, V-PL shunt, V-SSS shunt, V-C shunt, and V-V shunt with variable outcomes [1, 5]. Using of the inferior vena cava as a CSF draining pathway through the femoral vein access as in our case is a rarely documented technique and only 6 cases are reported in the literature to date with good outcome [2,3,4]. This technique as explained is simple and applicable by most surgeons, as there is no need for major vascular exposure. In our case, although the patient continued post-operatively on prophylactic doses of LMWH, she developed several times distal shunt obstruction in average of 6 months’ period. A study by Vandersteene et al. [5] showed that the CSF-blood-foreign material interaction promotes clot formation, which might result in thrombotic shunt complications. Their model showed a significantly greater percentage of shunt surface covered with deposits when the shunts were infused with CSF rather than Ringer’s lactate solution (90% vs 63%). In our case, this complication was simply managed in out-patient basis by injection of 20 cc of heparin diluted with normal saline (heparin 1 IU/1 cc NS) into the valve. The shunt resumed functioning after injection 3 times. In the last obstruction, management with percutaneous heparin injection failed. The patient was admitted and femoral vein shunt was removed and the tip of the shunt was found obstructed with coagulum. The advantage of this technique can be weighed over these complications, especially in the absence of other alternatives. In such cases, we recommend this technique as a salvage surgery until the patient become older with higher success rates for V-PL shunt. In this case, we already had decided to return to V-F-C shunt if the last V-PL shunt failed and to try V-PL shunt later in older age. During this period, we were accepting the complication of recurrent distal catheter obstruction because of its low morbidity and simplicity of management in absence of other alternatives.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

References

Kulkarni AV, Riva-Cambrin J, Butler J, Browd SR, Drake JM, Holubkov R, Kestle JR, Limbrick DD, Simon TD, Tamber MS, Wellons JC 3rd, Whitehead WE, Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network (2013) Outcomes of CSF shunting in children: comparison of Hydrocephalus Clinical Research Network cohort with historical controls: clinical article. J Neurosurg Pediatr 12(4):334–338

Gutiérrez-González R, Rivero-Garvía M, Márquez-Rivas J (2010) Ventriculovascular shunts via the femoral vein: a temporary feasible alternative in pediatric hydrocephalus. J Pediatr Surg 45(11):2274–2277

Philips MF, Schwartz SB, Soutter AD, Sutton LN (1997) Ventriculofemoroatrial shunt: a viable alternative for the treatment of hydrocephalus. Technical note. J Neurosurg 86(6):1063–1066

Tubbs RS, Barnhart D, Acakpo-Satchivi L (2007) Transfemoral vein placement of a ventriculoatrial shunt. Technical note. J Neurosurg 106(1 Suppl):68–69

Vandersteene J, Baert E, Planckaert GMJ, Van Den Berghe T, Van Roost D, Dewaele F, Henrotte MMDM, De Somer F (2018) The influence of cerebrospinal fluid on blood coagulation and the implications for ventriculovenous shunting. J Neurosurg 1:1–8

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Bashar Abuzayed

Methodology: Bashar Abuzayed, Khaled Alawneh

Formal analysis and investigation: Nabil Al-zoubi, Ziad Bataineh

Writing - original draft preparation: Bashar Abuzayed, Liqaa Raffee

Writing - review and editing: Bashar Abuzayed, Majdi Al Qawasmeh

Supervision: Bashar Abuzayed.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abuzayed, B., Al-zoubi, N., Bataineh, Z. et al. Ventriculo-femoro-caval shunt: a salvage surgery. Childs Nerv Syst 37, 2413–2415 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04919-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-020-04919-6