Abstract

Introduction

The increasing use of intracranial imaging has led to more frequent diagnoses of arachnoid cysts (ACs). Although ACs are a frequent finding on neuroimaging in children, the prevalence and natural history of these cysts are not well defined. Most ACs may persist and remain asymptomatic throughout life and not require treatment. However, there have been some case reports of ACs that have become larger or smaller over time and, in rare cases, have even spontaneously resolved. It is the authors’ practice to recommend serial neuroimaging in patients with asymptomatic sylvian ACs and not offer surgery to patients without symptoms, even in those with a relatively large cyst.

Case report

The present article describes a case involving a 6-year-old boy with a large, asymptomatic AC in the left Sylvian fissure involving the temporo-frontal region, which resolved spontaneously during the 2-year follow-up period after initial diagnosis without any surgical intervention. Currently, at the 7-year follow-up, the patient has remained neurologically intact, attends school, and is symptom-free.

Conclusion

Clinicians should be mindful of the possibility of spontaneous regression when encountering patients with asymptomatic and/or incidentally diagnosed sylvian ACs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although ACs are a frequent finding on neuroimaging in children, the exact prevalence and natural history of these cysts are not well understood. In adults, most ACs may remain stable and asymptomatic throughout life, and do not require surgical treatment [1]. In the pediatric population, however, it is unclear whether AC is stable or static. There are some case reports describing ACs that have become larger or smaller over time and, in rare cases, even spontaneously resolved [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9].

We report a rare pediatric case of a relatively large temporo-frontal AC that disappeared spontaneously during a 3-year-follow-up period without any surgical intervention.

Case report

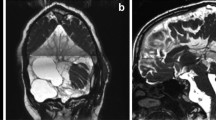

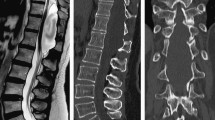

A 5-year-old boy presented with an incidentally discovered AC on computed tomography (CT) performed at a local hospital after being hit with a baseball bat while playing with friends of the same age. CT scans revealed a relatively large AC in the left side Sylvian fissure involving the fronto-temporal region, and a small subdural hygroma in the left frontal region (Fig. 1). Because there were no subjective symptoms or objective neurological signs at the time, further follow-up on an outpatient basis was pursued. CT scans performed at 6 years of age revealed a progressively decreased size of the AC (Fig. 2). When the patient was 8 years old, the cyst had virtually disappeared (Fig. 3).

During the clinical course, no other head injuries occurred and no intracranial inflammation, headache, or neurological deficits developed. Currently, during the 7 years of follow up, the patient remains neurologically intact, and his school life is very active without any symptoms.

Discussion

The majority of ACs may be static and remain asymptomatic throughout life and not require treatment [1, 10]. However, even spontaneous regression of ACs has been reported in the literature on rare occasion [3, 4, 6,7,8]. It remains unclear whether the size of most ACs remains unchanged, and whether AC is a static disease.

Al-Holou et al. reported that cyst enlargement occurred in 11 of 111 patients diagnosed with ACs incidentally, all of which initially presented at age < 4 years [11]. Lee et al. reported that 82.4% of patients who exhibited enlargement of ACs were < 1 year of age, and none of the patients > 3 years of age exhibited enlargement during follow-up [12]. These two reports suggest that there is a greater likelihood that the size of the cyst will increase if AC is diagnosed at an earlier age. It has also been reported that the larger the size of the AC at the time of diagnosis, the larger it becomes. Beck et al. comparatively analyzed the expansion of ACs according to age, and reported that small ACs exhibited no correlation with age, while large ACs correlated positively with age [2]. More specifically, the younger the age at diagnosis or the larger the size of AC, the greater the likelihood of AC growth while aging.

Another natural course of AC is spontaneous rupture. Although not common, cases of spontaneous regression of AC following rupture have been reported. Different mechanisms have been proposed to explain the spontaneous resolution of AC including head trauma and intracranial infection [5, 13,14,15]. There are some cases in which no clearly defined event affected the AC [7, 8, 16,17,18,19]. Head trauma, which is a major mechanism of spontaneous regression, often results in a tear of the cystic membrane; consequently, cystic fluid leaks into and is absorbed in the subarachnoid or subdural spaces [5, 20, 21].

The brain is a mobile structure and, despite being situated in the intracranial cavity, it “floats” in CSF and is shaking continuously, similar to a boat in a mobile water tank. Therefore, the membrane of ACs may be easily ruptured by minor trauma that does not cause injury to normal brain tissues or structures.

In the present case, the AC spontaneously regressed after minor trauma without intracranial injury. There have been many reported cases of spontaneous regression of ACs with a history similar to ours [3, 16, 19, 22, 23]. Hence, we suspect there is a history of minor trauma that was not recognized in most cases of spontaneous AC regression. As mentioned, brain tissue around the AC―or the AC itself―can be easily damaged by movement; therefore, cyst rupture may occur by mechanisms such as Valsalva maneuver, straining, sneezing, crying, or an unnoticed, presumably trivial injury. This is supported by the fact that spontaneous regression of ACs occur most frequently in the temporo-frontal sylvian region, which is most vulnerable to inertial injury [15]. When the AC membrane tears and cystic fluid is released and absorbed, a child’s brain is still developing and is expandable nature; the compressed brain will expand and fill the space previously occupied by the AC, resulting in disappearance of the cyst.

The spontaneous regression of ACs is not common in adults because the brains of adults are more of a fixed structure than a child’s brain [1, 11]. In other words, AC tears are not common and, even if AC tear occurs, brain expansion does not occur and AC size is not reduced as easily in adults.

Tear of the AC membrane does not always lead to good results. As the membrane of the AC tears, cystic fluid may spill into the subdural space rapidly, leading to increased intracranial pressure or, conversely, CSF may be entrapped within the cyst, which may increase its size. It may cause intracystic or subdural hemorrhage, resulting in symptomatic disease from an asymptomatic state [24,25,26,27]. For this reason, a significant number of neurosurgeons prefer to prophylactic surgical treatment of asymptomatic sylvian AC, according to the survey on the practical management of sylvian fissure AC [28]. However, as Di Rocco pointed out, in the case of sylvian arachnoid cyst, subdural hygroma requiring reoperation after surgery is highly likely to occur as a complication [29]. Hence, we agree that simple follow-up rather than surgical treatment may be a good choice unless there are serious symptoms.

In conclusion, we believe that sylvian AC is not a static disease in children. In children, a sylvian AC is easily ruptured, which may induce regression or become symptomatic. This phenomenon may occur naturally and gradually, or may be triggered by minor or major trauma. Therefore, we strongly recommend close observation with periodic imaging, even though the size of the sylvian AC is large or gradually increases, if there are no symptoms.

References

Al-Holou WN, Terman S, Kilburg C, Garton HJ, Muraszko KM, Maher CO (2013) Prevalence and natural history of arachnoid cysts in adults. J Neurosurg 118:222–231

Becker T, Wagner M, Hofmann E, Warmuth-Metz M, Nadjmi M (1991) Do arachnoid cysts grow? A retrospective CT volumetric study. Neuroradiology 33:341–345

Cokluk C, Senel A, Celik F, Ergur H (2003) Spontaneous disappearance of two asymptomatic arachnoid cysts in two different locations. Minim Invasive Neurosurg 46:110–112

Moon KS, Lee JK, Kim JH, Kim SH (2007) Spontaneous disappearance of a suprasellar arachnoid cyst: case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst 23:99–104

Poirrier AL, Ngosso-Tetanye I, Mouchamps M, Misson JP (2004) Spontaneous arachnoid cyst rupture in a previously asymptomatic child: a case report. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 8:247–251

Seizeur R, Forlodou P, Coustans M, Dam-Hieu P (2007) Spontaneous resolution of arachnoid cysts: review and features of an unusual case. Acta Neurochir 149:75–78

Weber R, Voit T, Lumenta C, Lenard HG (1991) Spontaneous regression of a temporal arachnoid cyst. Childs Nerv Syst 7:414–415

Yamauchi T, Saeki N, Yamaura A (1999) Spontaneous disappearance of temporo-frontal arachnoid cyst in a child. Acta Neurochir 141:537–540

Yuksel MO, Gurbuz MS, Senol M, Karaarslan N (2016) Spontaneous subdural haematoma developing secondary to arachnoid cyst rupture. J Clin Diagn Res 10:pd05–pd06

Huang JH, Mei WZ, Chen Y, Chen JW, Lin ZX (2015) Analysis on clinical characteristics of intracranial arachnoid cysts in 488 pediatric cases. Int J Clin Exp Med 8:18343–18350

Al-Holou WN, Yew AY, Boomsaad ZE, Garton HJ, Muraszko KM, Maher CO (2010) Prevalence and natural history of arachnoid cysts in children. J Neurosurg Pediatr 5:578–585

Lee JY, Kim JW, Phi JH, Kim SK, Cho BK, Wang KC (2012) Enlarging arachnoid cyst: a false alarm for infants. Childs Nerv Syst 28:1203–1211

Mori T, Fujimoto M, Sakae K, Sakakibara T, Shin H, Yamaki T, Ueda S (1995) Disappearance of arachnoid cysts after head injury. Neurosurgery 36:938–941

Yoshioka H, Kurisu K, Arita K, Eguchi K, Tominaga A, Mizoguchi N, Tajima T (1998) Spontaneous disappearance of a middle cranial fossa arachnoid cyst after suppurative meningitis. Surg Neurol 50:487–491

Bristol RE, Albuquerque FC, McDougall C, Spetzler RF (2007) Arachnoid cysts: spontaneous resolution distinct from traumatic rupture. Case report. Neurosurg Focus 22:E2

Beltramello A, Mazza C (1985) Spontaneous disappearance of a large middle fossa arachnoid cyst. Surg Neurol 24:181–183

Inoue T, Matsushima T, Tashima S, Fukui M, Hasuo K (1987) Spontaneous disappearance of a middle fossa arachnoid cyst associated with subdural hematoma. Surg Neurol 28:447–450

Rakier A, Feinsod M (1995) Gradual resolution of an arachnoid cyst after spontaneous rupture into the subdural space. Case report. J Neurosurg 83:1085–1086

Wester K, Gilhus NE, Hugdahl K, Larsen JL (1991) Spontaneous disappearance of an arachnoid cyst in the middle intracranial fossa. Neurology 41:1524–1526

van der Meche FG, Braakman R (1983) Arachnoid cysts in the middle cranial fossa: cause and treatment of progressive and non-progressive symptoms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 46:1102–1107

Dodd RL, Barnes PD, Huhn SL (2002) Spontaneous resolution of a prepontine arachnoid cyst. Case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosurg 37:152–157

Mokri B, Houser OW, Dinapoli RP (1994) Spontaneous resolution of arachnoid cysts. J Neuroimaging 4:165–168

Nadi M, Nikolic A, Sabban D, Ahmad T (2017) Resolution of middle fossa arachnoid cyst after minor head trauma–stages of resolution on mri: case report and literature review. Pediatr Neurosurg 52:346–350

Domenicucci M, Russo N, Giugni E, Pierallini A (2009) Relationship between supratentorial arachnoid cyst and chronic subdural hematoma: neuroradiological evidence and surgical treatment. J Neurosurg 110:1250–1255

Mori K, Yamamoto T, Horinaka N, Maeda M (2002) Arachnoid cyst is a risk factor for chronic subdural hematoma in juveniles: twelve cases of chronic subdural hematoma associated with arachnoid cyst. J Neurotrauma 19:1017–1027

Parsch CS, Krauss J, Hofmann E, Meixensberger J, Roosen K (1997) Arachnoid cysts associated with subdural hematomas and hygromas: analysis of 16 cases, long-term follow-up, and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 40:483–490

Kaszuba MC, Tan LA, Moftakhar R, Kasliwal MK (2018) Nontraumatic subdural hematoma and intracystic hemorrhage associated with a middle fossa arachnoid cyst. Asian J Neurosurg 13:116–118

Tamburrini G, Dal Fabbro M, Di Rocco C (2008) Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts: a survey on their diagnostic workout and practical management. Childs Nerv Syst 24:593–604

Di Rocco C (2010) Sylvian fissure arachnoid cysts: we do operate on them but should it be done? Childs Nerv Syst 26:173–175

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lim, JW., Choi, SW., Song, SH. et al. Is arachnoid cyst a static disease? A case report and literature review. Childs Nerv Syst 35, 385–388 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-018-3962-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-018-3962-z