Abstract

The clinical benefit of thrombus aspiration (TA) in patients presenting with acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not well defined. Furthermore, there is a large variation in the use of TA in real-world registries. Between 2005 and 2008, a total of 7146 consecutive patients with acute STEMI undergoing primary PCI were prospectively enrolled into the PCI Registry of the Euro Heart Survey Programme. For the present analysis, patients treated additionally with TA (n = 897, 12.6 %) were compared with those without TA (n = 6249, 87.4 %). Patients with hemodynamic instability at initial presentation (15.1 vs. 11.0 %; p < 0.001) and resuscitation prior to PCI (10.4 vs. 7.4 %; p = 0.002) were more frequently treated with TA. TIMI flow grade 0/1 before PCI was more often found among those with TA (73.5 vs. 58.6 %; p < 0.001). After adjustment for confounding factors in the propensity score analysis, TA was not associated with improved in-hospital survival (risk difference −1.1 %, 95 % confidence interval −2.7 to 0.6 %). In this European real-world registry, the rate of TA use was low. Hemodynamically unstable patients were more likely to be treated with TA. Consistent with the results of the TASTE study and the TOTAL trial, TA was not associated with a significant reduction in short-term mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite considerable clinical progress in recent decades and a decline in acute and long-term mortality, acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is still a critical medical condition. A key therapeutic component is the rapid establishment of coronary and myocardial reperfusion by percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) as the treatment of choice [34]. The final outcome of STEMI is influenced by many variables such as comorbidity, time delay to treatment, bleeding complications and resulting left ventricular ejection fraction [18]. Another decisive factor is the TIMI flow and, even more important, myocardial reperfusion after PCI [24, 27]. The initial thrombus load at the culprit lesion site may increase the risk of distal embolization of thrombotic material, either spontaneously or peri-procedurally, which could reduce distal flow or lead to no-reflow, thus impairing reperfusion of viable myocardium [3, 6, 12, 19]. While routine use of distal protection devices does not promote a beneficial outcome and is thus not recommended, thrombus aspiration (TA) has recently shown mixed results [2, 15, 30]. The objective of several prospective trials within the last few years was to clarify whether routine TA in patients presenting with STEMI contributes to a reduced mortality. After the first promising results, mainly based on the single-centre “Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial Infarction Study” (TAPAS trial), routine TA has been integrated into European and American STEMI guidelines likewise as a class IIa recommendation, although not all studies have shown positive effects [4, 25, 28, 30, 33]. TAPAS, however, was not powered to clinical endpoints. Recent results of the largest randomized trials to date, the “Thrombus Aspiration during PCI in Acute Myocardial Infarction” (TASTE) study and the “Randomized Trial of Primary PCI with or without Routine Manual Thrombectomy” (TOTAL) trial, have not shown any significant differences in all-cause mortality, rehospitalisation or stent thrombosis after a maximum of one-year follow-up period [10, 14, 17]. These results suggest that routine use of TA is not necessary as a standard procedure in STEMI patients, but may be considered in selected patients, leading to a downgrade in the ESC Revascularization Guidelines to IIb [35].

The purpose of this analysis was to investigate the use and the clinical outcome of TA in a European real-world registry. Within the large Euro Heart Survey PCI Registry, which prospectively enrolled unselected patients from 2005 to 2008, we compared STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI alone with those with primary PCI and additional peri-procedural TA.

Methods

The PCI Registry of the Euro Heart Survey Programme

The PCI Registry is a prospective, multi-centre, observational study of current practice with unselected patients undergoing elective or emergency PCI. A total of 47,407 consecutive patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or stable coronary artery disease (CAD) were recruited within the period from May 2005 to April 2008. The participating hospitals were located throughout Europe (176 centres in 33 ESC countries) and included university hospitals, community hospitals, specialist cardiology centres and private hospitals all providing PCI. The mean annual PCI volume of the participating facilities was approximately 1000. Details have been previously reported [1].

During specified periods, all patients treated with PCI were prospectively registered and followed during their clinical course to document patient characteristics, adjunctive medical treatment, procedural details and in-hospital outcomes.

Definitions

STEMI was diagnosed in the presence of the three following criteria: persistent angina pectoris for ≥20 min, new ST-segment elevations at the J point with the cut-off points ≥0.2 mV in V 1 through V 3 and ≥0.1 mV in other leads or the presence of a (presumed) new left bundle branch block and an elevation of troponin T or I levels. Post-procedural reinfarction was diagnosed if patients had signs of recurrent ischemia and an additional relevant increase in cardiac biomarkers. Bleeding complications were classified as major when the patient had an intracranial bleed or an overt clinical bleeding with a drop in haemoglobin of greater than 5 g/dl. Chronic renal failure was diagnosed by any of the following criteria: serum creatinine >2 mg/dl or 200 μmol/l in the past, on dialysis, or history of renal transplantation.

Data collection

Upon admission, data on patient characteristics were recorded, including age, gender, cardiovascular risk factors, concomitant diseases, prior myocardial infarction, prior stroke, prior cardiovascular interventions and chronic medical treatment, as well as data on symptoms and pre-hospital delay. Data on ECG findings, biochemical markers, procedural details and adjunctive therapy were also documented. At discharge, major cardiovascular or cerebrovascular adverse events, puncture site complications and recommended medical treatment were recorded.

Every participating centre was committed to include every consecutive patient undergoing PCI during the selected time periods. All patients gave written informed consent for processing their anonymous data. Electronic case report forms were used for data entry and transferred via the web to a central database located in the European Heart House, where they were edited for missing data, inconsistencies and outliers. Additional editing of the data and the statistical analyses for this publication was performed at the Institut fuer Herzinfarktforschung Ludwigshafen, Germany. The study was approved by the ethics committees responsible for the participating centres as required by local rules.

Statistical methods

Categorical data are presented as absolute numbers and percentages, metrical data as mean ± standard deviation or medians. The frequencies of categorical variables in two populations were compared by Pearson’s χ 2 test, and the distributions of metrical variables by the Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon test. Descriptive statistics were calculated from the available cases.

Furthermore, we evaluated the effect of TA on hospital mortality using propensity score methodology. In order to assess the imbalance in the distribution of risk factors between the treatment groups, the standardized mean difference (SMD) was used [1]. Values >0.1 of the SMD were regarded as indicative of potential confounding, so in addition to age and sex the following variables were included in the propensity score model: diabetes mellitus, prior resuscitation/cardiogenic shock, congestive heart failure, prior PCI, prior CABG (coronary artery bypass grafting), transradial access, TIMI flow grade 0/1 before PCI, type B and type C lesion, 3-vessel disease and treatment of left anterior descending (LAD). The control group was weighted by the odds of the propensity score to allow estimation of the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT).

P values ≤0.05 were considered significant. All p values are results of two-tailed tests. The statistical computations were performed with the SAS© system release 9.3 on a personal computer (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

Study population

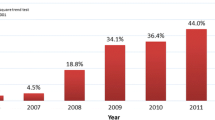

A total of 47,407 consecutive patients with ACS and stable CAD were enrolled in the Euro Heart Survey PCI Registry. Of these, 7146 had an acute STEMI. Out of these patients, 897 (12.7 %) were treated with TA in addition to PCI of the culprit lesion and were compared to those with lone primary PCI (n = 6249, 87.4 %). During the years of enrolment, the use of TA more than doubled (Table 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients (Table 2) demonstrate an equal distribution of demographic features. Patients with an increased incidence of hemodynamic instability at initial presentation (15.1 vs. 11.0 %; p < 0.001) and prior resuscitation (10.4 vs. 7.4 %; p = 0.002) were more likely to be treated with TA.

Angiographic and interventional characteristics

Although in most cases, the femoral artery was the preferred arterial access, a radial approach was more often performed in patients with TA (12.3 vs. 8.4 %; p < 0.001) (Table 3). There were no differences between the total number of stenosed vessels but patients with TA were more likely to have a single-vessel intervention (82.6 vs. 77.2 %; p < 0.001), which in most cases was the right coronary artery (RCA) (46.5 vs. 40.2 %; p < 0.001). The rate of TIMI flow grade 0/1 before PCI was higher in those patients referred for TA (73.5 vs. 58.6 %; p < 0.001). After PCI TIMI, flow grade 3 was less frequently observed in patients receiving TA (86.2 vs. 90.2 %; p < 0.001).

Pre- and peri-procedural medication

Before and during PCI, no differences were observed in the administration of GP IIb/IIIa antagonists (51.8 vs. 53.2 %; p = 0.42). Inotropic agents were more frequently applied in patients with TA (15.2 vs. 11.0 %; p < 0.001).

Procedural complications

In patients undergoing TA, peri-procedural coronary perforation was more common (1.0 vs. 0.3 %; p < 0.001) (Table 4). No differences were noted concerning the incidence of subsequent cardiac tamponade, acute segment closure and emergency CABG. Distal embolization and acute stent thrombosis were likewise equally distributed between groups. A no-flow or slow-flow phenomenon was more often observed in patients undergoing TA (5.7 vs. 3.2 %; p < 0.001). Patients with TA required a cardiac pacemaker more often and were more frequently subjected to cardioversion and defibrillation (4.5 vs. 2.3 %; p < 0.001 and 4.2 vs. 1.8 %; p < 0.001). Intra-aortic balloon pump and respiratory ventilation were evenly applied between the groups.

Patient outcome

The univariate analysis for patient outcome (Fig. 1) shows no difference in in-hospital death rate among patients, irrespective of treatment (5.5 vs. 5.7 %, p = 0.73). MACE (major adverse cardiac events) and MACCE (major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events) were significantly lower in patients with TA due to a diminished occurrence of non-fatal myocardial reinfarction (7.2 vs. 9.4 %; p = 0.03; 7.4 vs. 10.0 %; p = 0.01), despite lower TIMI patency. Non-fatal stroke alone was not significantly different (0.2 vs. 0.6 %; p = 0.21). A higher incidence of major bleeding was found among those with TA (2.8 vs. 1.4 %; p = 0.003). No major difference in the occurrence of renal failure requiring dialysis was observed between the two groups.

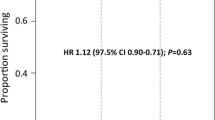

In the propensity score analysis (Table 5), TA was not associated with improved in-hospital survival (risk difference −1.1 %, 95 % confidence interval −2.7 to 0.6 %), but with a significant reduction of MACE and MACCE. TA had no effect on renal failure requiring dialysis, but was linked to a higher rate of major bleeding.

Discussion

Recent data from randomized trials investigating the role of TA in patients with STEMI, including meta-analyses of these trials, have shown inconsistent results with respect to mortality [2, 5, 7, 23]. In this large real-world cohort from the Euro Heart Survey PCI Registry, patients with a single, primary PCI were compared to those being treated additionally with TA. Only a minority of 12.6 % of all patients underwent TA. Our period of observation covered the years 2005–2008, during which there was a tendency towards an increase in the use of TA over time. One has to bear in mind, however, that the results of the TAPAS trial, which showed a mortality benefit, were published in 2008 [33]. Other real-world registries with more recent data have shown a utilization of TA between 18 and 62 %, with the highest rates documented in patients with TIMI flow grade 0/1 prior to intervention [9, 11, 16, 20–22, 26, 29, 32].

In our study, TA was used more often in patients presenting with hemodynamic instability and prior resuscitation. Also, patients with totally occluded infarct vessels were more likely to be treated with TA. These factors are important predictors for in-hospital mortality [13]. Therefore, it appears from our data that TA was used as a rescue method rather than as a routine procedure. Due to this selection bias, TIMI flow grade 3 after PCI was less frequently observed in patients with TA. Remarkably, only one registry confirmed the finding of an increased use of TA in hemodynamically unstable patients [29], while other registries did not demonstrate any significant differences in Killip class prior to PCI [11, 21, 22, 29, 32].

Surprisingly, GPIIb/IIIa antagonists were not given more often with TA, although their administration is an established therapy to improve coronary microcirculation and reduce major cardiac adverse events, presumably with the highest impact in lesions with a high thrombus burden and impaired TIMI flow [8, 31].

The findings concerning an increased incidence of cardioversion and implantation of temporary pacemakers in patients with TA can be linked to the higher rate of totally occluded vessels and the anatomical differences in the primary treated vessel. Surprisingly, the RCA represented the most commonly treated vessel in patients with TA and is notoriously associated with increased incidence of higher grade AV block and sinus arrest in acute coronary syndromes [8].

After adjustment for confounding factors in the propensity score analysis, TA was not linked to an improved in-hospital survival, but the occurrence of MACE and MACCE in TA patients was significantly lower. Compared with other registries, the follow-up period of the present registry is rather short, yet most other registries with up to three years of follow-up have not shown significant advantages for TA in STEMI patients [9, 16, 21, 26, 29]. Others have shown positive results for TA in patients with proximal culprit lesions, anterior infarcts and low TIMI flow [11, 20, 22]. In summary, our data are consistent with the results of the TASTE study and the TOTAL trial, showing no reduction in mortality in patients with STEMI treated with TA compared to PCI alone.

Limitations

As the nature of the study is exploratory, the findings should be interpreted cautiously. In the Euro Heart Survey PCI Registry, the treatment, including the choice of the individual TA technique, was left to the discretion of the physician. This could result in selection bias, which cannot be fully eliminated by using a propensity score analysis. Unfortunately, we do not have one-year follow-up data. Moreover, the study population enrolled is not contemporary, since the enrolment was performed between 2005 and 2008.

Conclusions

In this large European registry, the use of TA was low. Hemodynamically unstable patients were more often treated with TA. After adjustment for confounding factors in the propensity score analysis, TA was not associated with a significant reduction in mortality.

References

Bauer T, Mollmann H, Weidinger F, Zeymer U, Seabra-Gomes R, Eberli F, Serruys P, Vahanian A, Silber S, Wijns W, Hochadel M, Nef HM, Hamm CW, Marco J, Gitt AK (2011) Predictors of hospital mortality in the elderly undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes and stable angina. Int J Cardiol 151:164–169

Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Bhatt DL (2008) Role of adjunctive thrombectomy and embolic protection devices in acute myocardial infarction: a comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur Heart J 29:2989–3001

Block PC, Elmer D, Fallon JT (1982) Release of atherosclerotic debris after transluminal angioplasty. Circulation 65:950–952

Brener SJ, Witzenbichler B, Maehara A, Dizon J, Fahy M, El-Omar M, Dambrink JH, Genereux P, Mehran R, Oldroyd K, Parise H, Gibson CM, Stone GW (2013) Infarct size and mortality in patients with proximal versus mid left anterior descending artery occlusion: the Intracoronary Abciximab and Aspiration Thrombectomy in Patients With Large Anterior Myocardial Infarction (INFUSE-AMI) trial. Am Heart J 166:64–70

Burzotta F, De Vita M, Gu YL, Isshiki T, Lefevre T, Kaltoft A, Dudek D, Sardella G, Orrego PS, Antoniucci D, De Luca L, Biondi-Zoccai GG, Crea F, Zijlstra F (2009) Clinical impact of thrombectomy in acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: an individual patient-data pooled analysis of 11 trials. Eur Heart J 30:2193–2203

Colavita PG, Ideker RE, Reimer KA, Hackel DB, Stack RS (1986) The spectrum of pathology associated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty during acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 8:855–860

De Luca G, Navarese EP, Suryapranata H (2013) A meta-analytic overview of thrombectomy during primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol 166:606–612

De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Stone GW, Antoniucci D, Tcheng JE, Neumann FJ, Van de Werf F, Antman EM, Topol EJ (2005) Abciximab as adjunctive therapy to reperfusion in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 293:1759–1765

Fernandez-Rodriguez D, Alvarez-Contreras L, Martin-Yuste V, Brugaletta S, Ferreira I, De Antonio M, Cardona M, Marti V, Garcia-Picart J, Sabate M (2014) Does manual thrombus aspiration help optimize stent implantation in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction? World J Cardiol 6:1030–1037

Frobert O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, Omerovic E, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Aasa M, Angeras O, Calais F, Danielewicz M, Erlinge D, Hellsten L, Jensen U, Johansson AC, Karegren A, Nilsson J, Robertson L, Sandhall L, Sjogren I, Ostlund O, Harnek J, James SK (2013) Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 369:1587–1597

Hachinohe D, Jeong MH, Saito S, Kim MC, Cho KH, Ahmed K, Hwang SH, Lee MG, Sim DS, Park KH, Kim JH, Hong YJ, Ahn Y, Kang JC, Kim JH, Chae SC, Kim YJ, Hur SH, Seong IW, Hong TJ, Choi D, Cho MC, Kim CJ, Seung KB, Chung WS, Jang YS, Rha SW, Bae JH, Park SJ (2012) Clinical impact of thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention: results from Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. J Cardiol 59:249–257

Henriques JP, Zijlstra F, Ottervanger JP, de Boer MJ, van ‘t Hof AW, Hoorntje JC, Suryapranata H (2002) Incidence and clinical significance of distal embolization during primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 23:1112–1117

Jinnouchi H, Sakakura K, Wada H, Arao K, Kubo N, Sugawara Y, Funayama H, Momomura S, Ako J (2014) Transient no reflow following primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels 29:429–436

Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, Meeks B, Pogue J, Rokoss MJ, Kedev S, Thabane L, Stankovic G, Moreno R, Gershlick A, Chowdhary S, Lavi S, Niemela K, Steg PG, Bernat I, Xu Y, Cantor WJ, Overgaard CB, Naber CK, Cheema AN, Welsh RC, Bertrand OF, Avezum A, Bhindi R, Pancholy S, Rao SV, Natarajan MK, ten Berg JM, Shestakovska O, Gao P, Widimsky P, Dzavik V (2015) Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med 372:1389–1398

Kelbaek H, Terkelsen CJ, Helqvist S, Lassen JF, Clemmensen P, Klovgaard L, Kaltoft A, Engstrom T, Botker HE, Saunamaki K, Krusell LR, Jorgensen E, Hansen HH, Christiansen EH, Ravkilde J, Kober L, Kofoed KF, Thuesen L (2008) Randomized comparison of distal protection versus conventional treatment in primary percutaneous coronary intervention: the drug elution and distal protection in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (DEDICATION) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 51:899–905

Kilic S, Ottervanger JP, Dambrink JH, Hoorntje JC, Koopmans PC, Gosselink AT, Suryapranata H, van ‘t Hof AW (2014) The effect of thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention on clinical outcome in daily clinical practice. Thromb Haemost 111:165–171

Lagerqvist B, Frobert O, Olivecrona GK, Gudnason T, Maeng M, Alstrom P, Andersson J, Calais F, Carlsson J, Collste O, Gotberg M, Hardhammar P, Ioanes D, Kallryd A, Linder R, Lundin A, Odenstedt J, Omerovic E, Puskar V, Todt T, Zelleroth E, Ostlund O, James SK (2014) Outcomes 1 year after thrombus aspiration for myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 371:1111–1120

Lin TH, Lai WT, Kuo CT, Hwang JJ, Chiang FT, Chang SC, Chang CJ (2014) Additive effect of in-hospital TIMI bleeding and chronic kidney disease on 1-year cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndrome: data from Taiwan Acute Coronary Syndrome Full Spectrum Registry. Heart Vessels 30(4):441–450

MacDonald RG, Feldman RL, Conti CR, Pepine CJ (1984) Thromboembolic complications of coronary angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 54:916–917

Mangiacapra F, Wijns W, De Luca G, Muller O, Trana C, Ntalianis A, Heyndrickx G, Vanderheyden M, Bartunek J, De Bruyne B, Barbato E (2010) Thrombus aspiration in primary percutaneous coronary intervention in high-risk patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a real-world registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 76:70–76

Messas N, Hess S, Adraa AE, Ristorto J, Goiorani F, Brocchi J, Radulsecu B, Jesel L, Zupan M, Ohlmann P, Morel O (2014) Impact of manual thrombectomy on myocardial reperfusion as assessed by ST-segment resolution in STEMI patients treated by primary PCI. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 107:672–680

Minha S, Kornowski R, Vaknin-Assa H, Dvir D, Rechavia E, Teplitsky I, Brosh D, Bental T, Shor N, Battler A, Lev E, Assali A (2012) The impact of intracoronary thrombus aspiration on STEMI outcomes. Cardiovasc Revasc Med 13:167–171

Mongeon FP, Belisle P, Joseph L, Eisenberg MJ, Rinfret S (2010) Adjunctive thrombectomy for acute myocardial infarction: a bayesian meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 3:6–16

Morishima I, Sone T, Okumura K, Tsuboi H, Kondo J, Mukawa H, Matsui H, Toki Y, Ito T, Hayakawa T (2000) Angiographic no-reflow phenomenon as a predictor of adverse long-term outcome in patients treated with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for first acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:1202–1209

O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso JE, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX (2013) 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 127:529–555

Puymirat E, Aissaoui N, Cottin Y, Vanzetto G, Carrie D, Isaaz K, Valy Y, Tchetche D, Schiele F, Steg PG, Simon T, Danchin N (2014) Effect of coronary thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention on one-year survival (from the FAST-MI 2010 Registry). Am J Cardiol 114:1651–1657

Resnic FS, Wainstein M, Lee MK, Behrendt D, Wainstein RV, Ohno-Machado L, Kirshenbaum JM, Rogers CD, Popma JJ, Piana R (2003) No-reflow is an independent predictor of death and myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J 145:42–46

Silva-Orrego P, Colombo P, Bigi R, Gregori D, Delgado A, Salvade P, Oreglia J, Orrico P, de Biase A, Piccalo G, Bossi I, Klugmann S (2006) Thrombus aspiration before primary angioplasty improves myocardial reperfusion in acute myocardial infarction: the DEAR-MI (Dethrombosis to Enhance Acute Reperfusion in Myocardial Infarction) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 48:1552–1559

Siudak Z, Mielecki W, Dziewierz A, Rakowski T, Legutko J, Bartus S, Bryniarski KL, Partyka L, Dudek D (2015) No long-term clinical benefit from manual aspiration thrombectomy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients. Data from NRDES registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 85:E16–E22

Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Borger MA, Di Mario C, Dickstein K, Ducrocq G, Fernandez-Aviles F, Gershlick AH, Giannuzzi P, Halvorsen S, Huber K, Juni P, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Lenzen MJ, Mahaffey KW, Valgimigli M, van ‘t Hof A, Widimsky P, Zahger D (2012) ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 33:2569–2619

Stone GW, Grines CL, Cox DA, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, Griffin JJ, Guagliumi G, Stuckey T, Turco M, Carroll JD, Rutherford BD, Lansky AJ (2002) Comparison of angioplasty with stenting, with or without abciximab, in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 346:957–966

Valente S, Mattesini A, Lazzeri C, Chiostri M, Giglioli C, Meucci F, Baldereschi GJ, Cordopatri C, Gensini GF (2014) Thrombus aspiration in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: does it actually impact on long-term outcome? Cardiol J. doi:10.5603/CJ.a2014.0061

Vlaar PJ, Svilaas T, van der Horst IC, Diercks GF, Fokkema ML, de Smet BJ, van den Heuvel AF, Anthonio RL, Jessurun GA, Tan ES, Suurmeijer AJ, Zijlstra F (2008) Cardiac death and reinfarction after 1 year in the Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction Study (TAPAS): a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet 371:1915–1920

Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, de Belder M, Knot J, Aaberge L, Andrikopoulos G, Baz JA, Betriu A, Claeys M, Danchin N, Djambazov S, Erne P, Hartikainen J, Huber K, Kala P, Klinceva M, Kristensen SD, Ludman P, Ferre JM, Merkely B, Milicic D, Morais J, Noc M, Opolski G, Ostojic M, Radovanovic D, De Servi S, Stenestrand U, Studencan M, Tubaro M, Vasiljevic Z, Weidinger F, Witkowski A, Zeymer U (2010) Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe: description of the current situation in 30 countries. Eur Heart J 31:943–957

Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, Collet JP, Cremer J, Falk V, Filippatos G, Hamm C, Head SJ, Juni P, Kappetein AP, Kastrati A, Knuuti J, Landmesser U, Laufer G, Neumann FJ, Richter DJ, Schauerte P, Sousa Uva M, Stefanini GG, Taggart DP, Torracca L, Valgimigli M, Wijns W, Witkowski A (2014) 2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS)Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 35:2541–2619

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

K. F. Weipert, T. Bauer contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Weipert, K.F., Bauer, T., Nef, H.M. et al. Use and outcome of thrombus aspiration in patients with primary PCI for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: results from the multinational Euro Heart Survey PCI Registry. Heart Vessels 31, 1438–1445 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-015-0754-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-015-0754-1