Abstract

To date, no study has investigated how landscape structural (visual) alterations affect navigation and thus homing success in stingless bees. We addressed this question in the Australian stingless bee Tetragonula carbonaria by performing marking, release and re-capture experiments in landscapes differing in habitat homogeneity (i.e., the proportion of elongated ground features typically considered prominent visual landmarks). We investigated how landscape affected the proportion of bees and nectar foragers returning to their hives as well as the earliest time bees and foragers returned. Undisturbed landscapes with few landmarks (that are conspicuous to the human eye) and large proportions of vegetation cover (natural forests) were classified visually/structurally homogeneous, and disturbed landscapes with many landmarks and fragmented or no extensive vegetation cover (gardens and plantations) visually/structurally heterogeneous. We found that proportions of successfully returning nectar foragers and earliest times first bees and foragers returned did not differ between landscapes. However, most bees returned in the visually/structurally most (forest) and least (garden) homogeneous landscape, suggesting that they use other than elongated ground features for navigation and that return speed is primarily driven by resource availability in a landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anthropogenic activities can severely affect and alter bee communities by converting natural habitats into landscapes with reduced resource availability and diversity, and by increasing exposure to pesticides and non-native pathogens (Winfree et al. 2009; Potts et al. 2010; Roulston and Goodell 2011; Vanbergen and the Insect Pollinators Initiative 2013; Goulson et al. 2015). Anthropogenic activities can further alter the structure of the bees’ foraging landscape with severe consequences for foraging patterns and success (Steffan-Dewenter and Kuhn 2003; Westphal et al. 2006; Williams and Kremen 2007; Osborne et al. 2008; Kaluza et al. 2016).

While bee foraging success and thus fitness are predominantly affected by habitat related changes in resource availability and diversity (Roulston and Goodell 2011), the mere change of landscape (visual) structure, e.g., from spatially complex forests to uniform fields, may additionally affect foragers, e.g., by interfering with their navigation system, and therefore either benefit or impede foraging. This aspect has, to the best of our knowledge, not yet been examined.

Most studies on the navigation system of bees have focused on honeybees (Apis mellifera, Apidae: Apini) with their sophisticated recruitment system (von Frisch 1967). However, findings for honeybees most likely apply to most bee species, as orientation systems appear to be similar across invertebrates and even vertebrates (Dyer and Could 1983). Like other insects, bees combine a geocentric and egocentric navigation system, i.e., they integrate all distances and angles traveled into a home vector and further memorize landmarks to infer their position in relation to the environment, with visual information (‘view-based matching’) typically dominating over path integration in experienced foragers (Wehner et al. 1996; Menzel et al. 1996; Wystrach and Graham 2012; Menzel and Greggers 2015). They further use optical flow (i.e., integrate images moving in the eye) to assess travel distance between prominent landmarks while flying from nests to resource patches (Srinivasan 2014). Thus, bees appear to rely mostly on visual cues provided by the sky (i.e., polarized light) and the terrestrial environment to infer long-range directions and distances towards resource patches and their nest (Najera et al. 2015) with landmarks likely playing an important role (Menzel et al. 1996; Collett and Graham 2015).

The precise nature of visual landmarks used and memorized by bees is still subject to debate (Dyer et al. 2008; Wystrach and Graham 2012). Honeybees and stingless bees have trichromatic color vision peaking in the UV, blue and green region of the spectrum (Avarguès-Weber et al. 2012; Sánchez and Vandame 2012; Spaethe et al. 2014). They can thus perceive and memorize colors as well as visual shapes and patterns (Giurfa et al. 1999; Sánchez and Vandame 2012; Avarguès-Weber et al. 2012; Spaethe et al. 2014) and typically prefer global (i.e., the forest) over local (i.e., trees) patterns (Avarguès-Weber et al. 2015). Visual landmarks used in behavioral studies on navigation were often represented by shapes that are conspicuous to the human eye, including cars, tents, field margins (in field studies focusing on larger scales) and various paper shapes (in laboratory studies focusing on small scales) (Menzel et al. 1996; Fry and Wehner 2005). Radar tracking of inexperienced honeybee and bumblebee foragers suggested that they preferentially navigate along visual landmarks, i.e., elongated ground features, such as hedgerows, field margins or highways (Osborne et al. 2013; Collett and Graham 2015; Degen et al. 2015). Notably, such features conform with a very anthropogenic notion of landmarks (Wystrach and Graham 2012) and are most likely not found in the bees’ original habitat, which consisted of non-fragmented forest- or shrub-land. It may thus be more likely that bees, like ants and birds, rely on panoramic views for navigation, which would allow them to better cope with the complexity of natural landscapes given their poor visual resolution (Wystrach and Graham 2012).

Comparing navigation of bees foraging in differently structured landscapes may shed some more light on the sort of landmarks used. However, to our knowledge, it has not yet been investigated whether landscapes differing in their visual/spatial structure differently affect bee navigation, e.g., whether modern (disturbed) landscapes facilitate bee navigation compared with more natural (undisturbed) closed forest or shrub-land habitats.

We addressed this question by investigating how (visual) habitat structure affected homing success in a highly social bee species, the stingless bee Tetragonula carbonaria (Apidae, Meliponini), which not only occurs in the tropical and subtropical forests of Australia, but also thrives in human-dominated landscapes, such as cities (Dollin et al. 2009; Leonhardt et al. 2014b; Heard 2016).

We assumed that navigation in T. carbonaria was similar to honeybees and therefore facilitated in landscapes with landmarks that were conspicuous/prominent to the human eye. Based on this rather anthropogenic view, we consequently hypothesized that homing success (i.e., the proportion of bees returning to their hive within an hour and the earliest time first bees returned to their hives) increased with decreasing landscape homogeneity, i.e., from undisturbed forests (as visually homogenous landscapes with few, if any, prominent landmarks) to suburban areas (as visually heterogeneous landscapes with multiple prominent landmarks).

Methods

Study species and landscapes

The study was conducted in Queensland, Australia, between January and November 2013. Homing success was tested in the Australian stingless bee Tetragonula carbonaria (Apidae, Meliponini) (Dollin et al. 1997; genus change: Rasmussen and Cameron 2007), which is native to the study region, but can also be kept and propagated in boxes (Heard 2016).

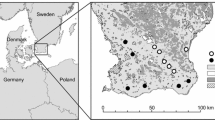

To test whether and how habitat alterations impact on homing success of T. carbonaria, we studied 11 colonies overall which had been experimentally placed in natural forests (four colonies) as well as two landscape types severely altered by humans, i.e., agricultural plantations (four colonies) and urban gardens (three colonies) (see Kaluza et al. 2016 for a detailed description of the study area, sites and landscape types) (Table 1; Fig. 1). Forests comprised relatively open Banksia heathland as well as denser sclerophyll forests with a closed canopy dominated by eucalypt species. Plantation sites comprised commercial macadamia plantations (Macadamia integrifolia Maiden and Betche X M. tetraphylla Johnson). Urban gardens in the study region typically included houses, surrounded by gardens of 300–1000 m2 with both native and exotic plants.

Examples for each of the three landscape types in which homing success was studied: (a) forest, (b) plantation and (c) garden. Circles give 500-m foraging radii around experimental hives. Habitat patches are outlined in color, i.e., green forest, purple garden, yellow plantation, and blue water. Circles indicate hive locations and blue and yellow arrows mark respective release points

Experimental setup

Overall 12 study sites had been established in 2011 (Kaluza et al. 2016), of which we used 7 for this experiment (Table 1). For each landscape type (plantation, forest and garden) we tested colonies at 2–3 study sites (Table 1). Hives with colonies had been mounted on metal posts roughly 1 m above ground (in forests and plantations) with the entrance facing NE. When posts could not be used due to sealed surfaces (in gardens), hives were placed on bricks close to the ground. All hives were located in shaded or semi-shaded locations and protected by a metal roof when not covered by house roofs. By the time the homing experiment started, all colonies were habituated to the location and surrounding foraging environment.

We anticipated a flight radius of 500 m around hives which is the typical foraging range of bees of this size (equivalent to 0.78 km2 flight range; Greenleaf et al. 2007; Smith et al. 2016). Flight ranges of different study sites did not overlap and more than 75 % of the flight range at each site was covered by the target landscape (plantation, forest or garden) (Kaluza et al. 2016).

Assessing habitat homogeneity

Honeybees can navigate along visual landmarks that are easily perceived by humans, i.e., elongated ground features (Osborne et al. 2013; Collett and Graham 2015; Degen et al. 2015). Such landmarks are more likely to occur in heterogeneous landscapes with changing habitat types, such as urban areas or extensively used agricultural landscapes with small fields intermixed with semi-natural habitat and forest patches.

We therefore considered undisturbed natural landscapes with few prominent landmarks and large proportions of area covered by vegetation (i.e., forests) visually/structurally homogeneous, and disturbed landscapes with many prominent landmarks and fragmented or no extensive vegetation cover (i.e., gardens and plantations) visually/structurally heterogeneous (Table 1; Fig. 1), which certainly represents a very anthropogenic classification. Landmarks that are conspicuous to the human eye [(i.e., water (ponds/creeks/rivers), roads/bridges, tall buildings and small patches of natural habitats)] were counted and vegetation cover (i.e., area covered by forest and/or plantations) assessed within the 500 m radius around hives using aerial photographs from Google Earth (Fig. 1). We outlined all vegetation patches to calculate their area with the software KML toolbox and additionally validated our classifications by ground surveys (Kaluza et al. 2016). To further test whether homing success depended on the type of vegetation cover (i.e., uniform plantations with only one tree species vs. diverse forests with many different tree species), we also assessed shrub and tree (i.e., woody plant) species richness by performing transect walks at each site (Kaluza et al., submitted).

Recording homing and foraging success

We caught 60 individuals from each study colony by placing a clean clear plastic bag over the entrance thereby capturing bees leaving the hive. In particular stingless bee pollen foragers are known to carry small amounts of highly concentrated nectar in their crops, used as either ‘fuel’ or ‘pollen glue’ (Leonhardt et al. 2007). To discourage bees from foraging, we therefore gently squeezed the bees’ abdomen forcing them to regurgitate all nectar stored in their crop. Foragers were then separated into two groups (each consisting of 30 individuals) and marked with two different colors (acrylic paint) by carefully holding them between two fingers, placing a small droplet of paint on their thorax using brushes or small twigs and waiting for the paint to dry. Because painted bees were observed foraging for resources even up to 10 days after the experiment, we are confident that handling and marking did not significantly impact on bees. All marked bees of one group were kept in clear plastic insect containers prior to release.

Two people then simultaneously walked 150 m into opposite directions (up- and down-wind) from the hive using geographic information system devices (GPS, Garmin, Germany) for orientation. We consider 150 m a typical foraging distance for T. carbonaria as this species was found to have a maximum flight range of 500 m (Smith et al. 2016). In preliminary trials, we had also tested other distances and found distances >100 m sufficient for detecting obvious differences in homing behavior while restricting the overall experiment duration.

Bees of both groups were released simultaneously by both experimenters by opening plastic containers and placing all bees on bare ground. We then waited for 10 min to ensure that all marked bees took flight. Bees which did not leave within this time period were re-collected and kept in plastic tubes until the end of the experiment.

A third observer at the hive entrance re-captured all bees returning in 5-min intervals for 1 h. All returning bees were again placed in plastic containers and visually inspected for either pollen or resin on their corbiculae or nectar in their crops (see above) to determine whether the bees had gone foraging. We noted the number of bees returning within each 5-min interval, the thorax color and whether or not bees carried any resources. Note that none of the returning bees carried any pollen or resin, but several had nectar in their crops, which is why we decided to account for nectar foraging and thus indirectly the availability of resources (which differs between landscapes, Kaluza et al. 2016) as a potential major factor determining return speed in our study. Homing success was calculated as the proportion of bees returning to their hives within 1 h (bees returned/bees released) and the earliest time (i.e., 5-min interval) the first bee returned to its hive. Nectar foraging was assessed as the proportion of returning nectar foragers (bees returned with nectar in crop/bees returned) and the earliest time (i.e., 5-min interval) the first nectar forager returned to its hive. We repeated the experiment for a total of 11 hives/performed a total of 11 trials (4 trials/hives in plantations, 3 trials/hives in gardens and 4 trials/hives in forests, Table 1).

Statistical analysis

To test whether releasing direction and thus wind influenced homing success and/or nectar foraging, we compared the proportion of bees returning within an hour, the earliest time (i.e., 5-min interval) the first bee returned and the first nectar forager returned as well as the proportion of nectar foragers using Wilcoxon matched pair tests. Data for both directions were pooled if releasing did not affect our response variables (which was the case for all variables but the proportion of foragers), while we included releasing direction as a random factor in a generalized linear mixed effect model (GLMM, lmer function in the lme4 package) if it did. Pooled data were compared between landscapes (forest, garden, plantation) by analyses of variances (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc tests. All data were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variances using Shapiro and Bartlett test, respectively, and log10- or arcsine square-root-transformed if these assumptions were not met. The earliest time the first bee returned did not pass tests for normality and homogeneity and was thus analyzed with a Kruskal–Wallis rank sum test.

To test whether single variables recorded for each site (i.e., area covered by vegetation, the richness of woody plant species, and the number of landmarks) better explained homing success and nectar foraging than landscape per se, we additionally composed generalized linear (mixed effect) models (GLMs, GLMMs) for each response variable. Because the area covered by vegetation and woody plant species richness were negatively correlated (Spearman’s correlation: r = −0.56, p = 0.035), we composed separate models for each explanatory variable. We finally used R 2 values to compare models comprising different explanatory variables (MuMIn package for R 2 values from GLMMs: Barton 2013; Nakagawa and Schielzeth 2013) except for models with the earliest time the first bee returned which could not be modeled with an appropriate distribution.

All statistical analyses were performed in R (R Development Core Team 2015).

Results

Homing success (i.e., the proportion of bees returning within 1 h) differed between landscapes (ANOVA: F = 10.99, p = 0.002). More bees returned within an hour in forests and gardens than in plantations (Table 1; Fig. 2a). The proportion of nectar foragers did not differ between landscapes (GLMM: χ 2 = 0.70, p = 0.855; Fig. 2b), neither did the arrival time of the earliest bee (Kruskal–Wallis test: χ 2 = 3.88, p = 0.144; Fig. 2c) or nectar forager (ANOVA: F = 1.32, p = 0.391; Fig. 2d).

Proportion of all released bees (a) and nectar foragers (b) returning within an hour as well as the earliest time (5-min interval) the first bee (c) and nectar forager (d) returned in plantations (P), gardens (G) and forests (F). Boxplots display the median (thick bar), lower (0.25) and upper (0.75) quartiles (gray box), minimum and maximum values (whiskers) and outliers (dots) of each dataset. Different letters indicate significant differences between landscapes (p < 0.05) according to Tukey post hoc tests. Overall, we performed 4 trials in plantations, 3 trials in gardens and 4 trials in forests

Models including only landscape as explanatory variables explained more variance in homing success and nectar foraging than models including the area covered by closed vegetation, number of landmarks, or woody plant species richness (Table 2). Arrival time of the earliest nectar forager was, however, best described by the model including woody plant species richness and landmarks (Table 2).

Discussion

In contrast to our expectations, homing was most successful, i.e., most bees returned, in undisturbed natural forest habitats as well as in heavily disturbed gardens. While gardens comprised a variety of elongated ground features which humans would easily use as landmarks for orientation and thus navigation, forests represented a visually homogenous structure to the human eye which had few, if any, conspicuous landmarks. This finding confirms that bees perceive landscapes very differently from humans (Wystrach and Graham 2012) and shows that they do not need seemingly conspicuous landmarks (such as elongated ground features) for navigation. In fact, like honeybees, stingless bees may be able to differentiate complex combinations of visual objects (typically existing in natural landscapes) and thus easily navigate in seemingly homogeneous forests (Dyer et al. 2008). However, because closed forests represent more than a choice between two similar complex landmarks (as tested by Dyer et al. 2008) and light conditions change over time (potentially affecting visual landmark features), stingless bees may additionally integrate knowledge on the current position of celestial cues (e.g., polarized light or the position of the sun) with a panoramic memory of the entire landscape to reliably infer their position at any time, as has been shown for honeybees (Towne and Moscrip 2008).

Alternatively (or additionally), they may rely on other than visual cues for navigation, e.g., olfactory cues emanating from environmental sources such as different tree species. In fact, olfactory navigation is widely found across the animal kingdom (Jacobs 2012); and honeybees are known to use olfactory cues (i.e., floral scents) when communicating resource quality and location within hives (Farina et al. 2005) and when locating communicated food sources at close range in the field (Reynolds et al. 2009; Menzel and Greggers 2013). Stingless bees further use complex volatile blends to locate preferred resin sources (Leonhardt et al. 2010, 2014a; Wallace and Leonhardt 2015). Whether (stingless) bees can also use olfactory landmarks, e.g., the scent of flowering tree species or a rotting log, instead or in addition to visual landmarks for path integration and map memorizing, has, to our knowledge, not yet been investigated. Such olfactory mapping has however been demonstrated for desert ants (Cataglyphis fortis: Buehlmann et al. 2015) and should be subject to further study in bees.

Given that bees returned equally well in the most (forest) and least (garden) homogeneous landscape, their returning speed and thus the proportion of bees returning within an hour may have been mainly driven by the availability of nectar resources within the surrounding landscape, despite the handling procedure and removal of crop content. Although we did not expect bees to go foraging after having been squeezed, painted and kept in a plastic container for up to 30 min, we found bees returning with nectar in their crops, indicating that they nevertheless visited flowers for nectar collection. In contrast, designated pollen or resin foragers may have returned directly (without any nectar in their crops). Moreover, mean and variance recorded for the earliest time the first nectar forager returned were highest in plantations (albeit not significantly different from other landscapes). Plantations provide the least woody plant species richness (Table 1) and thus likely the least nectar resources across seasons (Kaluza et al. 2016). Searching for scattered resources likely increases foraging durations, as has also been shown for bumblebees in agricultural landscapes (Westphal et al. 2006). Moreover, variance in the time the first forager returned was better captured by a model including woody plant species richness and landmarks than by the model, which included only landscape as explanatory variable, further stressing the importance of resource availability (i.e., plant species richness) in determining homing speed of nectar foragers. We therefore cannot rule out that reduced homing success in plantations was not (also) driven by limited resource availability.

To conclude, our study demonstrates that homing success in bees can be strongly affected by the surrounding foraging landscape. However, landscape structural/visual alteration (by disturbance) does not seem to provide more or less visual information used for navigation than undisturbed natural habitats, as bees returned equally fast and successfully in natural forests and human-altered urban garden areas. This finding indicates that return speed is primarily driven by resource availability in a landscape and suggests that elongated ground features are not necessary for orientation, at least not for stingless bees. In fact, we found only few, if any, such landmarks in forests, suggesting that stingless bees visually assess landscape differently from humans, or use complex combinations of visual objects or olfactory landmarks in more natural, seemingly homogeneous habitats. Future studies should thus quantify respective differences between landscapes as seen from the (stingless) bees’ perspective.

References

Avarguès-Weber A, Mota T, Giurfa M (2012) New vistas on honey bee vision. Apidologie 43(3):244–268

Avarguès-Weber A, Dyer AG, Ferrah N, Giurfa M (2015) The forest or the trees: preference for global over local image processing is reversed by prior experience in honeybees. Proc R Soc B 282:20142384

Barton K (2013) MuMIn: Multi-model inference. R package version 190 ed

Buehlmann C, Graham P, Hansson BS, Knaden M (2015) Desert ants use olfactory scenes for navigation. Anim Behav 106:99–105. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.04.029

Collett TS, Graham P (2015) Insect navigation: do honeybees learn to follow highways? Curr Biol 25(6):240–242

Degen J, Kirbach A, Reiter L, Lehmann K, Norton P, Storms M, Koblofsky M, Winter S, Georgieva PB, Nguyen H, Chamkhi H, Greggers U, Menzel R (2015) Honeybees apply effective exploration strategies during orientation flights. Anim Behav 102:45–57

Dollin AE, Dollin LJ, Sakagami SF (1997) Australian stingless bees of the genus Trigona (Hymenoptera: apidae). Invertebr Taxon 11(6):861–896

Dollin A, Walker K, Heard T (2009) Trigona carbonaria sugarbag bee (Tetragonula carbonaria). PaDIL - http://www.padilgovau:2012. Accessed Apr 2010

Dyer FC, Could JL (1983) Honey bee navigation: the honey bee’s ability to find its way depends on a hierarchy of sophisticated orientation mechanisms. Am Sci 71(6):587–597

Dyer AG, Rosa MGP, Reser DH (2008) Honeybees can recognise images of complex natural scenes for use as potential landmarks. J Exp Biol 211:1180–1186

Farina WM, Grüter C, Diaz PC (2005) Social learning of floral odours inside the honeybee hive. Proc R Soc B 272(1575):1923–1928

Fry SN, Wehner R (2005) Look and turn: landmark-based goal navigation in honey bees. J Exp Biol 208:3945–3955. doi:10.1242/jeb.01833

Giurfa M, Hammer M, Stach S, Stollhoff N, Müller-Deisig N, Mizyrycki C (1999) Pattern learning by honeybees: conditioning procedure and recognition strategy. Proc R Soc B 57:315–324

Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botias C, Rotheray EL (2015) Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347(6229):1255957. doi:10.1126/science.1255957

Greenleaf SS, Williams NM, Winfree R, Kremen C (2007) Bee foraging ranges and their relationship to body size. Oecologia 153:589–596

Heard TA (2016) The Australian native bee book. Keeping stingless bee hives for pets, pollination and sugarbag honey. Sugarbag Bees, Brisbane

Jacobs LF (2012) From chemotaxis to the cognitive map: the function of olfaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:10693–10700

Kaluza BF, Wallace HM, Heard TA, Klein A-M, Leonhardt SD (2016) Urban gardens promote bee foraging over natural habitats and plantations. Ecol Evol. doi:10.1002/ece1003.1941

Leonhardt SD, Dworschak K, Eltz T, Blüthgen N (2007) Foraging loads of stingless bees and utilisation of stored nectar for pollen harvesting. Apidologie 38:125–135

Leonhardt SD, Zeilhofer S, Schmitt T (2010) Stingless bees use terpenes as olfactory cues to find resin sources. Chem Senses 35:603–611

Leonhardt SD, Baumann A-M, Wallace HM, Brooks P, Schmitt T (2014a) The chemistry of an unusual seed disperal mutualism: bees use a complex set of chemical cues to find their partner. Anim Behav 98:41–51

Leonhardt SD, Heard TA, Wallace HM (2014b) Differences in the resource intake of two sympatric Australian stingless bee species. Apidologie 45(4):514–525. doi:10.1007/s13592-013-0266-x

Menzel R, Greggers U (2013) Guidance by odors in honeybee navigation. J Comp Phys A 199(10):867–873

Menzel R, Greggers U (2015) The memory structure of navigation in honeybees. J Comp Phys A 201(6):547–561

Menzel R, Geiger K, Chittka L, Joerges J, Kunze J, Müller U (1996) The knowledge base of bee navigation. J Exp Biol 199:141–146

Najera DA, McCullough EL, Jander R (2015) Honeybees use celestial and/or terrestrial compass cues for inter-patch navigation. Ethology 121:94–102. doi:10.1111/eth.12319

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H (2013) A general and simple method for obtaining R2 from generalized linear mixed-effects models. Method Ecol Evol 4(2):133–142

Osborne JL, Martin AP, Carreck NL, Swain JL, Knight ME, Goulson D, Hale RJ, Sanderson RA (2008) Bumblebee flight distances in relation to the forage landscape. J Anim Ecol 77(2):406–415

Osborne JL, Smith A, Clark SJ, Reynolds DR, Barron MC, Lim KS, Reynolds AM (2013) The ontogeny of bumblebee flight trajectories: from naïve explorers to experienced foragers. PLoS One 8:e78681

Potts SG, Biesmeijer JC, Kremen C, Neumann P, Schweiger O, Kunin WE (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trend Ecol Evol 25:345–353

R Development Core Team (2015) R: A language and environment for statistical computing, URL http://www.R-project.org. R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna

Rasmussen C, Cameron SA (2007) A molecular phylogeny of the old world stingless bees (Hymenoptera: apidae: Meliponini) and the non-monophyly of the large genus Trigona. Syst Entomol 32:26–39

Reynolds AM, Swain J-L, Smith AD, Martin AP, Osborne JL (2009) Honeybees use a levy flight search strategy and odour-mediated anemotaxis to relocate food sources. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 64:115–123

Roulston TH, Goodell K (2011) The role of resources and risks in regulating wild bee populations. Annu Rev Entomol 56:293–312

Sánchez D, Vandame R (2012) Color and shape discrimination in the stingless bee Scaptotrigona mexicana Guérin (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Neotrop Entomol 41(3):171–177. doi:10.1007/s13744-012-0030-3

Smith JP, Heard TA, Gloag AR, Beekman M (2016) Flight range of the Australian stingless bee, Tetragonula carbonaria (Hymenoptera, Apidae). Austral Entomol (in press)

Spaethe J, Streinzer M, Eckert J, May S, Dyer AG (2014) Behavioural evidence of colour vision in free flying stingless bees. J Comp Phys A 200(6):485–496

Srinivasan MV (2014) Going with the flow: a brief history of the study of the honeybee’s navigational odometer. J Comp Phys A 200(6):563–573

Steffan-Dewenter I, Kuhn A (2003) Honeybee foraging in differentially structured landscapes. Proc R Soc B 270(1515):569–575. doi:10.1098/rspb.2002.2292

Towne WF, Moscrip H (2008) The connection between landscapes and the solar ephemeris in honeybees. J Exp Biol 211:3729–3736

Vanbergen AJ, the Insect Pollinators Initiative (2013) Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators. Front Ecol Envir 11(5):251–259

von Frisch K (1967) The dance language and orientation of bees. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Wallace HM, Leonhardt SD (2015) Do hybrid trees inherit invasive characteristics? fruits of Corymbia torelliana XC. citridora hybrids and potential for seed dispersal bees. PLoS One 10(9):e0138868

Wehner R, Michel B, Antonsen P (1996) Visual navigation in insects: coupling of egocentric and geocentric information. J Exp Biol 199:129–140

Westphal C, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T (2006) Foraging trip duration of bumblebees in relation to landscape-wide resource availability. Ecol Entomol 31:389–394

Williams NM, Kremen C (2007) Resource distributions among habitats determine solitary bee offspring production in a mosaic landscape. Ecol Appl 17:910–921

Winfree R, Aguilar R, Vazquez DP, LeBuhn G, Aizen MA (2009) A meta-analysis of bees responses to anthropogenic disturbance. Ecology 90(8):2068–2076

Wystrach A, Graham P (2012) What can we learn from studies of insect navigation? Anim Behav 84:13–20. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.04.01

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Julia Nagler, Manuel Pützstück, Birte Hensen, Nora Drescher and Bradley Jeffers for assistance with field work. We further thank Sahara Farms, Macadamia Farm Management Pty Ltd and Maroochy Bushland Botanic Gardens, as well as numerous private land and garden owners to keep our bee hives and let us walk around their properties. We are further grateful for the comments of two anonymous reviewers, which helped to improve our manuscript. BFK received funding from the German Academic Exchange Agency (DAAD). The project was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), LE 2750/1-1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leonhardt, S.D., Kaluza, B.F., Wallace, H. et al. Resources or landmarks: which factors drive homing success in Tetragonula carbonaria foraging in natural and disturbed landscapes?. J Comp Physiol A 202, 701–708 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-016-1100-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00359-016-1100-5