Abstract

Introduction

Shared decision making (SDM) in surgical specialties was demonstrated to diminish decisional regret, decisional anxiety and decisional conflict. Urolithiasis guidelines do not explicit patient preference to choose treatment. The aim of this review article was to perform a systematic evaluation of published evidence regarding SDM in urinary stone treatment.

Methods

A systematic review in accordance PRISMA checklist was conducted using the MEDLINE (PubMed) database. Inclusion criteria were studies that evaluated stone treatment preferences. Reviews, editorials, case reports and video abstracts were excluded. ROBUST checklist was used to assess quality of the studies.

Results

188 articles were obtained. After applying the predefined selection criteria, seven articles were included for final analysis. Six out of seven studies were questionnaires that propose clinical scenarios and treatment alternatives. The last study was a patient preference trial. A general trend among included studies showed a patient preference towards the least invasive option (SWL over URS). The main reasons to choose one treatment over the other were stone-free rates, risk of complications and invasiveness.

Discussion

This review provides an overview of the patients’ preferences towards stone treatment in small- and medium-sized stones. There was a clear preference towards the least invasive management strategy. The main reason was less invasiveness. This is opposed to the global trends of performing more ureteroscopies and less SWL. Physicians played a pivotal role in counselling patients. SDM should be encouraged and improved. The main limitation of this study is the characteristics of the included studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Shared decision making (SDM) represents a shift from paternalistic practice to active engagement of the patient with the physician [1]. It aims to achieve high quality treatment decisions trough the sharing of knowledge between patient and their healthcare provider, whenever multiple options are considered clinically acceptable [2, 3]. It looks to improve que quality of medical decisions by helping patients choose options, delay or forego care altogether, concordant with their values and in accordance with the best available scientific evidence [2]. Adoption of SDM in surgical specialties was demonstrated to diminish decisional regret, decisional anxiety and decisional conflict. At the same time, SDM does not decrease surgical volume and increases awareness and decisional satisfaction for the patients [4]. Most urologist reports that they use SDM during their daily practice [5]. EAU Urolithiasis guidelines [6] state that the treatment of urinary stones is based on several parameters and it is individualized for each patient, implying that patient preferences should be taken into consideration, without explicitly mentioning it. If we could incorporate patient reported outcomes, such as satisfaction, treatment expectations and health-related quality of life, we could learn how to better tailor each specific alternative option for our patients [7]. Against this background, the aim of this review article was to perform a systematic evaluation of published evidence about patient preferences and SDM in urinary stone treatment (surgical, medical and/or observation).

Methods

A systematic review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist was conducted [8]. A literature search was conducted by one author (FP), using the MEDLINE (PubMed) database, using keywords “endourology”, “urolithiasis”, “ureteroscopy”, in combination with each of the following “patient preferences”, “shared decision making” compiling them with “AND”. Search was done from inception to April 04, 2023. Inclusion criteria were studies that evaluated patient preferences in stone treatment. Duplicates were removed from screening, and reviews, editorials, case reports and video abstracts were excluded from the full-text eligibility assessment. No language exclusion criteria were used. The resulted studies were included for qualitative analysis. The literature analysis was done by one author (FP) and confirmed for final selection by one author (EV) previous assessment to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Data extraction about objective of the studies, method to assess patient preference, results of each study concerning decision of the patient and the reasons (when stated) to choose one treatment over other alternative. Finally, the conclusions were also tabulated. Utility value and percentage were the main effect measures used in the presentation of results.

The risk of bias utilized for surveys tool (ROBUST) [9] was used to assess the quality of all studies by one author. The ROBUST checklist eight specific items. Each study was assigned a scores 0–8. Studies scoring 8 points representing the highest level of confidence (low risk of bias) and 0 the lowest level (high risk of bias) (Table 1).

According to the substantial degree of heterogeneity among the included studies in terms of both design and outcomes, we report here a narrative synthesis of the results.

Results

A total of 188 articles were obtained from the literature research (Fig. 1). After applying the predefined selection criteria, seven articles were included for final analysis. The following management strategies for stone disease were analysed: observation/active surveillance, medical expulsive therapy (MET), shock wave lithotripsy (SWL), and endourological procedures. In detail, one study evaluated patient attitudes regarding medical expulsive therapy (MET) solely [10]. Of the six remaining studies, four compared patients preferences for surgical or medical treatments (including observation/active surveillance) [1, 11,12,13]. Eventually, two studies investigated only surgical alternatives [14, 15] (Table 2).

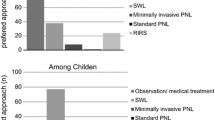

The studies included in this synthesis are rather heterogeneous. Most of the studies [1, 10,11,12,13,14] were questionnaires with clinical scenarios proposed to patients with either active or recent history of stone disease. In detail, five out of seven studies proposed clinical scenarios for renal stones and offered those treatment alternatives detailing stone-free and complications rates. The preferred treatment in all studies was extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) [1, 11,12,13,14]. A preference trial [15] enrolled and treated patients either with ureteroscopy (URS) or SWL, and evaluated the degree of which patients would choose the same treatment modality again in the future and SWL was significantly above URS in the patient preferences. PCNL was the least option, even with medium-sized stones (15–20 mm) scenarios URS was preferred over PCNL [12, 13]. Up to 56–85% of the patients relied on the physician recommendations for the treatment modality [1, 12]. A general trend among included studies showed a patient preference towards the least invasive option. The main reasons to choose one treatment over the other was stone-free rates (SFR), risk of complications and invasiveness.

Discussion

Our results show a clear preference of patients with stone disease towards the least invasive management strategy. In medium-sized stones, URS is preferred over PCNL. Key factors in treatment choice were stone-free rates (SFR), risk of complications and invasiveness. During decision making, physicians played a pivotal role in counselling patients.

Shared decision making implies that whenever patients are offered a range of clinical options, both benefits and harms should be clearly disclosed. In terms of SFR after URS, we now know that the real-life numbers are not as good as are results coming from trials [16]. A study that looked over 6000 ureteroscopies in multiple centers reported an average SFR of 49.6% for renal and 72.7% for ureteral stones [17]. The studies included in this review and offered URS to the enrolled patients indicating a potential stone-free rate for renal stones between 70 and 90% [1, 12,13,14]. This underlines that the data we use to inform our patients during shared decision making should reflect more precisely real-world numbers. Ideally, each surgeon should inform patients with updated results coming from the retrospective analysis of her/his series, in terms of both efficacy and complications [18]. Surprisingly, despite this possible bias, most patients preferred SWL over URS.

This is even more compelling given that that ureteroscopy has currently become the most frequently active treatment modality for urolithiasis in many countries [19]. Its use has increased over 250% in total number of treatments performed, with a share of total treatments increase by 17%. Conversely, SWL is performed less and less with an opposite trend as compared to URS and a share of total treatments decrease by 14.5%. PCNL has a more or less static rate [19]. As whole, URS diffusion and utilization keeps increasing despite an apparent patient preference towards SWL. This can be explained by the fact that up to 85% of patients would rely on the physician’s recommendation for the treatment modality [1, 12], and ureteroscopy may be more attractive to perform by practicing urologists. However, when urologists were asked what treatment would they prefer for a < 1 cm lower pole stone, 52.3% choose observation, 25.5% SWL, and only 16.1% URS [20], making the understanding of the general picture even more difficult. In addition, it must be considered that probably many centers are not still fully equipped with SWL, making a bias in the treatment decision/recommendation.

A systematic review that evaluated SDM and surgery conclude that data is limited regarding this topic in the surgical literature, which is similar to our results. In addition, they stated that patients and surgeon expressed preference towards SDM [21].

One more key point has to be considered during SDM, i.e., how we provide information to our patients [2]. Information must be given tailor made to our patients to adapt it to their cultural, educational and social background. We have to consider that there is also a nocebo effect, which is opposite to the placebo. Nocebo means that poor outcomes result, because patients believe that the outcome will be negative [22]. It means that socially given negative expectations and their emotional associations facilitate their own realization [23]. One striking example of this effect is that women from the Framingham study who believed that they were more likely than others to suffer a heart attack were 3.7 times as likely to die of coronary conditions as were women who believed that they were less likely, independently of commonly risk factors [24]. Considering the urological literature, some years ago, a study assessed sexual side effects of finasteride comparing two treated groups, one of those was not counselled about finasteride side effects. Sexual side effects were three times more in the counseled group compared to the control [25]. Being the nocebo phenomenon a side effect of human culture [23], we recommend informing patients during the SDM as to adhere to quality standards.

Back in 2019, a survey was done by the AUA [5] about SDM with more than 2200 urologist answering this census. Overall, 77% reported that they regularly use SDM in at least one clinical scenario. 66.3% of the urologist responded yes to four or more SDM elements that were asked about urolithiasis. Surprisingly, only 66% of the sample reported asking patients about their values and preferences for urolithiasis. The lowest reported that SDM adoption rates were seen in urinary incontinence and pediatric vesicoureteral reflux, 63 and 50%, respectively. Strikingly urologist practicing in academic settings were less likely to report SDM use. However, only 9% of decisions met the definition of SDM completeness in another study [26] and almost half of patients with urolithiasis report decisional conflict [27].

As a whole, 84% of urologist reported that they felt no barriers to routine use of SDM [5]. Anyhow, the main barriers associated with SDM are differences between guidelines recommendations and patient preferences for a certain scenario. In addition, an emergency setting differs from an elective one. Actually, it has been reported that patients in an emergency setting were much more likely to sign the consent form regardless of its content compared to elective surgery (93 vs 39%) [28]. Another concern is the time needed to give a complete explanation of available alternatives to the patient. The more trained we are the more efficient we will be. Decisional aids are tools frequently used in SDM for improving knowledge sharing and facilitating the decision process [4]. The use of decisional aids has demonstrated to have a positive impact on level of knowledge and diminish decisional conflict for patients with symptomatic non-lower pole stone < 20 mm [29]. Non-availability of specific equipment or technology can also undermine SDM process. There is a five-step approach (SHARE approach) [30] to SDM that outlines how health care professionals can ensure that they are effectively implementing shared decision making with patients during clinical encounters (Table 3). In addition, there is an updated version of how to implement SDM into urological practice published by the AUA that we encourage to look at [2]. This systematic review has some limitations due to the heterogenous study design of included articles, as well as their limited sample size.

This is the first review of patients’ preferences in stone treatment to our knowledge, and despite the limitations that this study has we think it puts a topic over the table about the real patient preferences compared to what urologist prefer to do and has available or encourage the patient to perform. We must consider that maybe our obsession with stone-free rates is not the most important factor to patients.

Conclusion

This systematic review reported the patients’ preferences regarding small- and medium-sized renal stones treatments. When patients decide for active treatment, they prefer the least invasive as first choice. The main reasons to choose one treatment over another are success rate, risk of complications and invasiveness. There is an incongruency between patients’ preferences (SWL) and treatment modalities perform worldwide (URS over SWL). SDM should be encouraged and improved.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

References

Omar M, Tarplin S, Brown R, Sivalingam S, Monga M (2016) Shared decision making: why do patients choose ureteroscopy? Urolithiasis 44(2):167–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-015-0806-0

Makarov D, Fagerlin A, Finkelstein J et al (2022) American Urological Association (AUA) implementation of shared decision making into urological American Urological Association (AUA) shared decision making. (April):1–19

Shirk JD, Crespi CM, Saucedo JD et al (2017) Does patient preference measurement in decision aids improve decisional conflict? A randomized trial in men with prostate cancer. Patient 10(6):785–798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-017-0255-7

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, Poenaru D (2020) Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 13(6):667–681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-020-00443-6

Lane GI, Ellimoottil C, Wallner L, Meeks W, Mbassa R, Clemens JQ (2020) Shared decision-making in urologic practice: results from the 2019 AUA census. Urology 145:66–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.06.078

Skolarikos A, Jung H, Neisius A et al (2023) EAU guidelines on urolithiasis. Eur Assoc Urol Guidel (March):1–20. https://www.uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/22-Urolithiasis_LR_full.pdf

Penniston KL, Nakada SY (2016) Treatment expectations and health-related quality of life in stone formers. Curr Opin Urol 26(1):50–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0000000000000236

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

Nudelman G, Otto K (2020) The development of a new generic risk-of-bias measure for systematic reviews of surveys. Methodology 16(4):278–298. https://doi.org/10.5964/METH.4329

Bell JR, Penniston KL, Best SL, Nakada SY (2017) A survey of patient preferences regarding medical expulsive therapy following the SUSPEND trial. Can J Urol 24(3):8827–8831

Kuo R, Aslan P, Abrahamse P, Matchar D, Preminger G (1999) Incorporation of patient preferences in the treatment of upper urinary tract calculi: a decision analytical view. J Urol 162(6):1913. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(05)67394-6

Sarkissian C, Noble M, Li J, Monga M (2013) Patient decision making for asymptomatic renal calculi: Balancing benefit and risk. Urology 81(2):236–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2012.10.032

Walters A, Massella V, Pietropaolo A, Seoane LM, Somani B (2022) Decision-making, preference, and treatment choice for asymptomatic renal stones-balancing benefit and risk of observation and surgical intervention: a real-world survey using social media platform. J Endourol 36(4):522–527. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2021.0677

Spradling K, Bhambhvani HP, Chang T et al (2021) Evaluation of patient treatment preferences for 15 to 20 mm kidney stones: a conjoint analysis. J Endourol 35(5):706–711. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2020.0370

Karlsen SJ, Renkel J, Tahir AR, Angelsen A, Diep LM (2007) Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy versus ureteroscopy for 5- to 10-mm stones in the proximal ureter: prospective effectiveness patient-preference trial. J Endourol 21(1):28–33. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2006.0153

Canvasser N, Lay A, Kolitz E, Antonelli J, Pearle M (2017) Mp75-12 Prospective evaluation of stone free rates by computed tomography after aggressive ureteroscopy. J Urol 197(4S):e1007–e1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2017.02.2160

Kim HJ, Daignault-Newton S, Dibianco JM et al (2022) Real-world practice stone-free rates after ureteroscopy from a surgical collaborative: Much to improve. Eur Urol 81:S1510–S1511. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0302-2838(22)01105-8

Montorsi F (2019) On having grey hair. Eur Urol 75(4):541–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2019.01.002

Geraghty RM, Jones P, Somani BK (2017) Worldwide trends of urinary stone disease treatment over the last two decades: a systematic review. J Endourol 31(6):547–556. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2016.0895

Ates F, Zor M, Yılmaz O et al (2016) Management behaviors of the urology practitioners to the small lower calyceal stones: the results of a web-based survey. Urolithiasis 44(3):277–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00240-015-0825-x

Shinkunas LA, Klipowicz CJ, Carlisle EM (2020) Shared decision making in surgery: a scoping review of patient and surgeon preferences. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 20(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-020-01211-0

Voelker R (1996) Nocebos contribute to host of ills. JAMA 275(5):345–347. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.275.5.345

Hahn RA (1997) The nocebo phenomenon: concept, evidence, and implications for public health. Prev Med (Baltim) 26(5):607–611. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1996.0124

Eaker ED, Pinsky J, Castelli WP (1992) Myocardial infarction and coronary death among women: psychosocial predictors from a 20-year follow-up of women in the Framingham study. Am J Epidemiol 135(8):854–864. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116381

Mondaini N, Gontero P, Giubilei G et al (2007) Finasteride 5 mg and sexual side effects: how many of these are related to a Nocebo phenomenon? J Sex Med 4(6):1708–1712. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00563.x

Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W (1999) Informed decision making in outpatient practice: time to get back to basics. JAMA 282(24):2313–2320. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.282.24.2313

Cabri JN, Saigal CS, Lambrechts S et al (2019) Decisional quality among patients making treatment decisions for urolithiasis. Urology 133:109–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2019.07.023

Maher DI, Serpell JW, Ayton D, Lee JC (2021) Patient reported experience on consenting for surgery—elective versus emergency patients. J Surg Res 265(September):114–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2021.03.026

Gökce MI, Esen B, Sancl A, Akplnar C, Süer E, Gülplnar Ö (2017) A Novel decision aid to support informed decision-making process in patients with a symptomatic nonlower pole renal stone <20 mm in diameter. J Endourol 31(7):725–728. https://doi.org/10.1089/end.2017.0077

The SHARE Approach—Essential Steps of Shared Decisionmaking: Expanded Reference Guide with Sample Conversation Starters. Ahrq 1–14. https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/curriculum-tools/shareddecisionmaking/tools/tool-2/index.html

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FP: project development, data collection, manuscript writing. EV: data collection, manuscript writing. OT: manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Prof. Olivier Traxer is a consultant for Coloplast, Rocamed, Olympus, EMS, Boston Scientific and IPG. Eugenio Ventimiglia and Felipe Pauchard have no potential conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This research did not involve Human Participants and/or Animals.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not used.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pauchard, F., Ventimiglia, E. & Traxer, O. Patient’s preferences: an unmet need by current urolithiasis guidelines: a systematic review. World J Urol 41, 3807–3815 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04678-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04678-4