Abstract

Purpose

Urinary incontinence (UI) is a common condition in women. The aim of this study is to analyze women with self-reported UI, focusing on socio-demographic data, health-related conditions and comorbidities, and their impact on healthcare resources.

Methods

We analyzed data from a population-based survey with a representative sample of Portuguese women aged ≥ 18 years (n = 10,465). Women with self-reported symptoms of UI were distributed according to age, education level, and household income. The comparison of comorbidities and use of healthcare resources between the UI and non-UI groups was adjusted for age, education, and body mass index. We computed weighted prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratios with 95% confidence intervals using Poisson regression.

Results

Female UI prevalence was 9.9%, increasing with age (6.3% for 18- to 39-year-old, 40.8% for 75- to 85-year-old women). The prevalence decreased with education level (36.8% in women with no education, 4.6% in women with more than 12 years of education) and household income (29.8% in the 2nd quintile of income, 9.9% in the 5th quintile). Women with UI had a higher level of comorbidities, especially cardiovascular, respiratory, and mental health disorders. UI was also associated with higher consumption of healthcare resources.

Conclusion

UI is highly prevalent among Portuguese women. It increases with age, low education level, and low household income. The use of healthcare resources was higher, possibly related with associated comorbidities. Though obtained in a single European country, these data may be useful to design a comprehensive management of UI in other parts of the western world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Urinary incontinence (UI), as defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) as the complaint of any involuntary leakage of urine, is a common disorder [1]. Different forms of UI are known, all affecting severely the patients' quality of life, and physical and mental well-being.

While lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have similar prevalence in men and women, UI is more frequent in women [2, 3]. However, when we look at the studies reporting UI prevalence, the range of values presented across different countries is wide enough to raise questions concerning the etiology of those geographic asymmetries, since the known pathophysiological mechanisms are the same. The reported results are not adjusted to factors such body mass index, income, or education, and this may be one of the reasons for such observed differences.

Nevertheless, the burden of UI goes far beyond its frequency. It is difficult to separate health impact from social effect. Studies indicate that incontinence is associated with stress and depression. But also, the embarrassment and decreased ability to participate in social activities may lead to social isolation, which may further erode their overall mental health. The same reports link UI with deterioration in sexual life, and as women may be reluctant to discuss their condition with their partner, UI can strain personal relationships [4,5,6,7]. Finally, women with UI may face some challenges in their workplaces, with different repercussions according to their jobs. The concern with potential odors and the frequent toilet breaks may result in decreased productivity and even absenteeism.

This loss of productivity is interrelated with the economic impact of UI, being one of their major components. The economic burden is also felt in the healthcare costs, both at an individual level and to the healthcare system. All the expenses with consultations, diagnostic exams, and different treatments (medications, physical therapy, surgery, pads, and diapers) can be significant in a condition that may be chronic. As this paper is being written, European Association of Urology is sending to their associates a press release claiming that UI costs European society over 40 billion euros per year in 2023, including all the aforementioned reasons and also the environmental impact of incontinence care. They estimate a total accumulated economic burden of 320 billion euros in 2030, if nothing is done otherwise in an aging society.

Here, we aimed to expand the analysis of the impact of self-reported UI regarding age, socio-demographic data, and comorbidities, and how these parameters influence quality of life and the use of healthcare resources.

Methods

The present analysis is based on data collected as part of the National Health Survey (NHS) 2014, which is a nationwide community-based cross-sectional study that evaluated a sample of the Portuguese population, obtained through multistage stratified and cluster sampling.

This survey was approved by ethics committee, and all subjects provided signed informed consent.

Population sampling and data collection

A sample of households was defined using data from the 2011 Population and Housing Census and was used as the sampling frame for household surveys conducted by the INE. It included 1183 primary sampling units (PSU), selected systematically within larger geographical strata, with a probability proportional to the number of households in each unit. A random sample of the households was then selected, and all persons 15 years of age or older living in these households at the date of the recruitment were eligible. In each household, the selected individual was the one whose previous birthday was closest to the date of the contact. The sample size was defined to ensure a homogeneous distribution of the participants by the nine Territorial Nomenclature Units for Statistical Purposes, level II (NUTS II) regions.

Between September and December 2014, a total of 22 538 households were contacted, and 18 204 persons (56.4% women) were evaluated. Data were collected using either computer-assisted personal interviewing or computer-assisted web interviewing (50% in each regional stratum). The questionnaire covered four thematic areas: health status, healthcare, health determinants, and income and health expenses.

The diagnosis of urinary incontinence was assessed in the section of chronic diseases, answering the question “Have you suffered from urinary incontinence or bladder control problems in the last 12 months?”.

A detailed description of the assessment of the participants’ associated comorbidities, mental health status, and healthcare consumption is presented.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was restricted to women aged ≥ 18 years that provided information on urinary incontinence, corresponding to a sample of 10,465 respondents.

We computed prevalence of urinary incontinence and used Poisson regression models to compute age- and education-adjusted prevalence ratios (PR) and respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) to compare women with and without urinary incontinence. All analyses were conducted with STATA, version 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA), using sampling weights computed based on the design weight, that is, the inverse of the probability of selection of each PSU and of each household within each PSU, further corrected for non-responses and for the effective number of subjects evaluated, regarding the age and gender structures.

Results

The nationwide prevalence of female self-reported UI was 9.9% (95%CI 9.1–10.8%). UI increased with age, from 2.0% (1.1–2.9%) for the 18- to 39-year-old age stratum to 28.9% (25.6–32.2%) for the 75- to 85-year-old women. The prevalence decreased with education level [28.2% (24.8–31.6%) to women with no education to 2.2% (1.2–3.2%) to women with more than 12 years of education]. Female UI prevalence also decreased with household income, ranging from 14.4% (12.3–16.4%) in the 2nd quintile of income to 5.3% (3.8–6.8%) in the 5th quintile.

Comorbidities

Women with UI had a high prevalence of comorbidities, especially hypertension [prevalence = 63.3% (95%CI: 59.0–67.5%)], obesity [27.8% (24.0–31.6%)], and diabetes mellitus [25.8% (22.0–29.7%)]. The age-, education-, and obesity-adjusted comparison between women with UI and those without UI demonstrated a higher level of respiratory [20% versus 8.6%, PR = 1.65 (95%CI 1.33–2.06)] and cardiovascular [24.8% versus 6%, PR = 1.69 (1.39–2.06)] diseases, and diabetes [25.8% versus 7.8%, PR = 1.40 (1.16–1.69)] (Fig. 1).

Comparison of the prevalence of depression diagnosis, use of mental health consultations, different dimensions of mental health disease and addictive behaviours between UI women and non-UI women. a Age-, education-, and BMI-adjusted prevalence ratio and corresponding 95% confidence interval: PR (95%CI)

Mental health

The estimated prevalence of depression among women with UI was 36.9%, being approximately 66% higher than the prevalence observed among women without UI, with depression in 15.6% of the cases [PR = 1.66 (1.43–1.92)]. Regarding the mental health assessment, the survey also identified a higher prevalence of self-perceived health status as bad [47.8% versus 13.5%, PR = 1.65 (1.46–1.88)], difficulty in concentrating [41.2% versus 20.7%, PR = 1.58 (1.381.82)], and a feeling of worthlessness or guilt during the last 2 weeks [48.6% versus 25.4%, PR = 1.49 (1.33–1.67)]. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding addictive behaviors (Fig. 2).

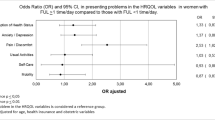

Use of healthcare resources

Female UI was associated with higher healthcare consumption, not only mental health evaluations [PR = 1.46 (1.06–2.00)] but also medical consultations in general [PR = 1.29 (1.19–1.39)], as well as prescribed medication [PR = 1.09 (1.05–1.14)] (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Several studies report female UI prevalence, with most of them estimating a percentage between 25 and 45% [8]. The larger studies, with the higher number of participants, included patients from several countries. In 2003, a study with women from France, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK) reported a 35% overall prevalence of self-reported involuntary loss of urine in the preceding 30 days [7]. The Epidemiology Urinary Incontinence and Comorbidities (EPIC) study, that recruited patients from Canada, Germany, Italy, Sweden, and the UK, described that the prevalence of UI in women was of 13.1% [2].

Further epidemiological analysis in this area, with the Epidemiology of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (EpiLUTS) study, carried in Sweden, the United States of America, and the UK estimated that UI in women ≥ 40 years was also highly prevalent. In spite of not reporting a global prevalence of UI, they noted that stress UI affected 31.8% of the responders, urgency UI 24.4%, and post-micturition UI 14.9% [3].

Our findings are in line with these data, with a nationwide prevalence of female UI of 9.9%, increasing with age, from 2.0% for 18- to 39-year-old to 28.9% for 75- to 85-year-old women. The rising prevalence with age is also consistent with the literature.

Our study adds an important information to the overall and age-related prevalence of UI, by analyzing for the first time the frequency of UI in conjunction with the educational level of affected women [2, 3]. In our analysis, it was clear that the prevalence varied with education level. UI was reported by 28.2% of women with low education in contrast with 2.2% among women with more than 12 years of education. The prevalence of UI was also inversely related to the household income, ranging from 14.4% in the 2nd quintile of income to 5.3% in the 5th quintile. This is surprising as one could expect that higher education and higher household income would increase the self-diagnosis and general knowledge about incontinence problems. However, there are some possible explanations to these numbers, considering that educational level and income may be interconnected. Women with lower education may have less knowledge about health in general and pelvic health in particular, regarding risk factors for UI and corresponding preventive measures. They are less likely to engage in a healthy lifestyle, which is one of the reasons why lower income populations have nowadays higher prevalence of smoking and obesity, two known risk factors for UI. Additionally, there is often a trend toward smaller family sizes as income rises, making lower income population more prone to higher parity, which is another risk factor to UI. They could also be more prone to certain occupations, more physically demanding or with more inflexible access to bathroom facilities, that may further exacerbate the condition. Furthermore, women with lower income have sometimes limited access to healthcare services, including not only treatment of UI but also preventive care. It is worth noting that this is particularly dramatic as this population with higher prevalence is precisely the one with more difficulties affording the costs of UI therapies and products.

We observed an association between women with UI and some comorbidities, such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. However, since this study applied a cross-sectional assessment, it is difficult to establish the causation link between the several comorbidities and the presence of female UI. Nevertheless, there are some possible justifications. Cardiovascular disease has a wide spectrum of manifestations. These patients have atherosclerosis and as a systemic disease it may have an impact in bladder arteries which, despite unproved, remains hypothesized as etiology to overactive bladder; they may have the need to take diuretics to control their hypertension or heart failure, or may simply be more prone to have obesity and diabetes as comorbidities. Regarding respiratory diseases, the presence of cough may increase awareness SUI. However, it may be also a consequence of attending more frequently medical facilities where women might be exposed to a better general medical care. By having more access to healthcare, it is possible that they become more aware that UI is a pathological condition and not a normal, integral part of aging, as sometimes patients unveil.

Regarding mental health domain, a subanalysis of the EpiLUTS study revealed that as the lower urinary tract symptoms increase, the outcomes in the questionnaires concerning quality of life, anxiety, and depression had worse outcomes [9]. Accordingly, the same survey showed that almost 50% of women with MUI and around 40% with UUI suffered from anxiety. In contrast, only 16.8% of women with pure SUI indicated some degree of depression [10]. Comparably, in our study, 60% of the women indicated a depressed mood, more than 1/3 had a diagnosis of depression and 10% were attending mental health consultations. Albeit there is not a proven cause effect link yet, incontinence undoubtedly affects mental health. The embarrassment caused by urine leakage in public places easily leads to isolation and depression. In this context urinary incontinence with an urgency component might be worse that pure stress incontinence due to its unpredictable characteristic. In addition, almost 50% perceived their health status as bad and reported a feeling of worthlessness. Interestingly, there were no relevant differences concerning addictive behaviors. Looking at this information, it is not surprising that incontinent women had higher healthcare consumption, including medical consultations, and received prescriptions.

In our view, what stands out of this evidence is that UI has a strong influence on women’s well-being. Perhaps physicians should pay more attention to UI reported by women and actively investigate their UI status, offer a diagnostic work-up, research treatment, and refer the patients to a Urologist whenever necessary. Information of the community in general is also a fundamental step in our society, where many times, for cultural reasons leakage of urine is seen as a normal event in the aging process of women and therefore not always reported spontaneously to the doctors.

Our findings, coming from a large population-based study in Portugal, can most probably apply to other western countries, and perhaps to other societies despite their different cultural norms, health perceptions, and access to healthcare. It is important to stress that despite being more prevalent among women from lower educational level and lower income population, UI affect women across all socioeconomic backgrounds. Public health initiatives to promote health education and increase access to early intervention may reduce socioeconomic disparities, diminish healthcare economic burden, and improve patients’ quality of life [11].

Conclusion

Urinary incontinence is highly prevalent in women, and it increases with age, low educational level, and low household income. Respiratory, cardiovascular, and mental health disorders are important independent comorbidities associated to female UI. The use of healthcare resources was also more prevalent among these women. Public health policies may mitigate this problem by raising awareness both in the population and in the clinicians. Education might prevent some cases by promoting healthier lifestyles and help reduce the impact of other cases by encouraging them to seek earlier treatment. A comprehensive approach to the condition is crucial.

References

Abrams P et al (2002) The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 21:167

Irwin DE et al (2006) Population-based survey of urinary incontinence, overactive bladder, and other lower urinary tract symptoms in five countries: results of the EPIC study. Eur Urol 50:1306

Coyne KS et al (2009) The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: results from the Epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int 104:352

Irwin DE et al (2006) Impact of overactive bladder symptoms on employment, social interactions, and emotional well-being in six European countries. BJU Int 97:96–100

Lai H et al (2015) Correlation between psychological stress levels and the severity of overactive bladder symptoms. BMC Urol 15:14

Balzarro M et al (2019) Impact of overactive bladder-wet syndrome on female sexual function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Med Rev 7:565–574

Hunskaar S et al (2004) The prevalence of urinary incontinence in women in four European countries. BJU Int 93:324

Hunskaar S et al (2005) Epidemiology of urinary incontinence (UI) and faecal incontinence (FI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP). In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A (eds) Incontinence, 3rd edn. Health Publication Ltd, Plymouth, UK, pp 255–312

Coyne KS et al (2009) The burden of lower urinary tract symptoms: evaluating the effects of LUTS on health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression: EpiLUTS. BJU Int 103(Suppl 3):4

Coyne KS et al (2012) Urinary incontinence and its relationship to mental health and health-related quality of life in men and women in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Eur Urol 61:88–95

Wagner T et al (2016) Economics of urinary and faecal incontinence, and prolapse. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Wagg A, Wein A (eds) Incontinence, 6th edn. Health Publications Ltd, Paris, pp 17–24

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Margarida Manso contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. Francisco Botelho performed data analysis. Cláudia Bulhões was responsible for project development and data collection. Francisco Cruz wrote the manuscript. Luís Pacheco-Figueiredo was involved in project development and data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. There is no funding to declare.

Ethics and Informed consent

This survey was approved by ethics committee, and all subjects provided signed informed consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Manso, M., Botelho, F., Bulhões, C. et al. Self-reported urinary incontinence in women is higher with increased age, lower educational level, lower income, number of comorbidities, and impairment of mental health. Results of a large, population-based, national survey in Portugal. World J Urol 41, 3657–3662 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04677-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04677-5