Abstract

Introduction

Calyceal diverticulum (CD) is the outpouching of a calyx into the renal parenchyma, connected by an infundibulum. Often associated with recurrent stones, common surgical options include percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) or retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS). We aim to present the real-world practises and outcomes comparing both approaches and the technical choices made.

Materials and methods

Retrospective data including 313 patients from 11 countries were evaluated. One hundred and twenty-seven underwent mini-PCNL and one hundred and eighty-six underwent RIRS. Patient demographics, perioperative parameters, and outcomes were analysed using either T test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data between groups were analysed using the Chi-squared test. Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed matching for baseline characteristics. Subgroup analyses for anomalous/malrotated kidneys and difficult diverticulum access were performed.

Results

After PSM, 123 patients in each arm were included, with similar outcomes for stone-free rate (SFR) and complications (p < 0.001). Hospitalisation was significantly longer in PCNL. Re-intervention rate for residual fragments (any fragment > 4 mm) was similar. RIRS was the preferred re-intervention for both groups. Intraoperative bleeding was significantly higher in PCNL (p < 0.032) but none required transfusion. Two patients with malrotated anatomy in RIRS group required transfusion. Lower pole presented most difficult access for both groups, and SFR was significantly higher in difficult CD accessed by RIRS (p < 0.031). Laser infundibulotomy was preferred for improving diverticular access in both. Fulguration post-intervention was not practised.

Conclusion

The crux lies in identification of the opening and safe access. Urologists may consider a step-up personalised approach with a view of endoscopic combined approach where required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Calyceal diverticulum (CD) is an outpouching of a calyx into the renal parenchyma, connected by a narrow infundibulum to the pelvicalyceal system. Aetiology may be congenital or arising from infection, vesicoureteric reflux or renal cyst rupture [1] and almost half arise from the upper pole, with 29.7% and 21.4% arising from middle and lower poles, respectively [2]. Most are asymptomatic and incidentally diagnosed. Recurrent pyelonephritis, abscess formation, microscopic haematuria as well as calculi formation are also seen.

Incidence of CD stones varies from 10 to 50%, due to urinary stasis and associated metabolic abnormalities [3]. PCNL was the traditional modality for success of access and stone extraction [4]. RIRS is widely accepted as a safe, minimally invasive alternative in the management of renal stones in adults [5], children [6] and even anomalous kidneys [7, 8]. There remains no consensus on the best approach for CD stone management due to the paucity of evidence, with clinicians generally opting for a stepwise approach from least to most invasive modalities [9, 10]. EAU guidelines suggest ESWL, PCNL, RIRS or even retroperitoneal laparoscopic diverticulectomy can be performed where feasible, as stone disintegration often alleviates symptoms [11].

Our study aims to present real-world practises and outcomes from a global multicentre cohort comparing PCNL and RIRS for CD stones. Our secondary aim is to highlight the technical choices made by surgeons concerning CD identification, access, lithotripsy, and exit strategy for each approach.

Materials and methods

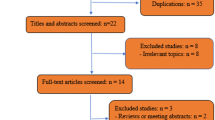

Anonymized pooled retrospective data of 313 patients from 11 countries were analysed. Patients aged ≥ 18 years with CD stones confirmed on pre-operative contrasted CT scan, who underwent RIRS or mini-PCNL between January 2017 and September 2022, were included. The preferred instrumentation such as single-use or disposable scope, single step or serial dilatation was based entirely on surgeon preferences and expertise. Anonymised pooled data were maintained in the ethics board approved registry of global trends in PCNL and RIRS intervention for CD (Maintained by Asian Institute of Nephrology and Urology 10/2022). Data collected included demographics, stone characteristics and intraoperative parameters including mode of identification, entry of diverticulum, exit strategy and surgical time—defined as time from cystoscopy to placement of double-J stent or percutaneous nephrostomy tube (PCN). Stone-free rate (SFR) was defined as no stone > 4 mm at imaging either by X-ray or CT scan done within 3 months during follow-up. Data regarding postoperative complications and secondary procedures were collected. This was evaluated using T test for continuous normally distributed variables and a Mann–Whitney U test for variables without normal distribution. Categorical data between groups were analysed using the Chi-squared test.

Propensity score matching (PSM) was performed between the two groups using the nearest-neighbour method and calliper size of 0.2, matching for baseline characteristics of age, gender, stone type (single < 1 cm, single > 1 cm, or multiple), diverticulum location, stone size and SFR assessment by at least one non-contrast CT scan. Identical analyses were repeated for the PSM cohort. Factors potentially influencing outcomes such as SFR and presence of residual fragments (RF) were analysed via univariate analysis (UVA). Potentially prognostic variables in UVA were entered into a generalised linear model for multivariate analysis (MVA), to assess their significance as independent predictors. Finally, two subgroup analyses were conducted for malrotated kidneys and difficult diverticulum access. Analyses were performed using statistical software (R-4.1.2) with p < 0.05 indicating statistical significance.

Results

Three hundred and thirteen patients were included. One hundred and twenty-seven patients had PCNL (Group 1) and one hundred and eighty-six underwent RIRS (Group 2). Table 1(A) describes the baseline cohorts before and after PSM. Post-PSM, there were 123 patients in each group. A similar number of asymptomatic patients were counselled for intervention in both groups. Pain was the most common reason for intervention (73.2% vs 73% in Group 1 vs Group 2). Recurrent stone formers, defined as patients with CD stone that was previously treated and recurred, were significantly higher in Group 2 (26.4% vs 15.1%, p < 0.05). Pre-PSM, the most common location of the CD was lower pole in Group 1 (42.5%) vs upper pole in Group 2 (34.2%). Group 2 had more patients with multiple stones and stones > 1 cm. Post-PSM, location of diverticulum, size and number of stones were equally matched. Patients with malrotated kidneys were more common in Group 1 (37.4 vs 27.2%, p < 0.051).

Table 1(B) demonstrates intraoperative characteristics. In both the groups, a similar usage of Thulium fibre laser or Holmium laser (HL < 50 W) was noted for lithotripsy. Pneumatic lithotripter (PL) was deployed in 44 cases in Group 1 and 9 of 12 cases in Group 2 who had endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery (ECIRS) to complete surgery. No difference was seen in total operating time between the two cohorts. At exit strategy in Group 1, 36.4% had a PCN alone, 27.3% used stents alone and 31.4% had both.

Table 1(C) outlines postoperative outcomes. Intraoperatively, on-table SFR by inspection was reportedly higher in Group 1 (82.9% vs 75.6%, p = 0.208). However, actual postoperative SFR was similar in both groups (71.5% vs 74.0%, p = 0.775), suggesting no significant difference by either intervention. Re-intervention rate for RF was also similar (12.2% vs 13%, p > 0.99). RIRS was the preferred mode for re-intervention. Although intraoperative bleeding was significantly higher in Group 1 (34.1% vs 21.1%, p < 0.032), none required blood transfusion. Four patients in Group 1 had a perirenal hematoma post-imaging but none required further intervention. Two patients in Group 2 required blood transfusions—both had pelvicalyceal injuries in a malrotated kidney, and one had a concurrent perirenal hematoma requiring embolization.

Table 2 shows the UVA for SFR. The odds of being stone-free were significantly higher in single stones (OR 2.694; 95% CI 1.522–4.82; p < 0.001) and the odds of having RF were significantly higher when stone was in the lower pole (OR 0.474, 95% CI 0.226–0.956, p = 0.041). On MVA (Supplementary Table 1), odds of being stone-free were only significant when managing a single stone (OR 2.10; 95% CI 1.11–3.99, p = 0.023), irrespective of location.

A separate subgroup analysis (Supplementary Tables 2–4) was performed for CD in malrotated kidneys (n = 81) and those with difficult access (n = 74). Difficult access was defined as CD with difficult intraoperative delineation, identification of opening or access into the cavity proper. In malrotated kidneys, lower pole CD was more commonly accessed by PCNL. In difficult access, upper pole CD was more commonly accessed by RIRS. Overall, lower pole CD presented greatest difficulty in access by either intervention. Intraoperative bleeding was the singular main complication when dealing with malrotated systems or difficult CD access, irrespective of intervention. RIRS has a significantly higher SRF in difficult access (78% vs 51.5%, p = 0.031), and whilst not significant, a similarly higher probability of single-stage SFR for malrotated kidneys (82.4% vs 66%, p = 0.166) was found.

Discussion

CD occurs most commonly in the upper pole, and can be classified as Type 1 or 2 based on communication with a minor or major calyx respectively, with no predilection for laterality [4]. Type 2 CD is often symptomatic—postulated by retrograde filling of urine with stasis and secondary stone formation [11]. Treatment modality must consider numerous factors including diverticular type, location, stone burden and size. The CD distribution in our cohort post-PSM is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1.

PCNL has been time tested, with studies reporting SFR of 83% and 90% success in rendering patients symptom–free [12]. Typically, this involves ureteral catheter placement, contrast delineation of the diverticulum, percutaneous access, tract dilatation and lithotripsy [2]. Traditionally, the diverticular neck is delineated with contrast and a guidewire placed across to widen with sequential dilatation [13]. Alternatively, identification can be performed with retrograde infusion of indigo carmine or carbon dioxide through the ureteral catheter [14]. In RIRS, the scope is steered to the contrast filled diverticulum and the opening identified visually. Classically, the methylene blue dye test is performed if opacification of the diverticulum is delayed or suboptimal. This technique has been well described by Lechevallier et al. [15] and well described in PCNL by Waigankar et al. [2]. In our series, the blue dye test was used in Group 1 (8.4%) more frequently than in Group 2 (4.9%) (Table 1B). A combination of direct visualisation and introduction of a guidewire into the CD possibly precluded the use of this technique in Group 2.

Monga et al. advocated subsequent dilatation and fulguration of CD which achieved 87.5% obliteration at 3-month follow-up [16]. Similarly, Shalav et al. [17] reported 83% obliteration rate, compared to 67% on dilatation alone. However, Eshgi et al. [18] and Hulbert JC et al. [19] do not advocate fulguration or electrocautery as this may traumatise the lining. Instead, PCN placement should suffice for granulation and re-epithelialization of the diverticular neck, for eventual obliteration to prevent recurrence. In our series, none of the surgeons reported usage of fulguration or electrocautery. Of note, laser infundibulotomy was done in 20.8% in Group 1 compared to 63.1% in Group 2. Sah et al. [20] reported a case of utilising Holmium laser for infundibulotomy in CD with settings of 200 μm, 1.0 J, 10 Hz and long pulse setting. Kim et al. [21] also reported a similar case in management of a stenotic infundibulum with Holmium. They reported it to be safe and efficient whilst avoiding the need for PCN. In our series, limitations include a lack of reporting of laser settings as well as a short follow-up period with imaging, as this could aid in commenting if those manoeuvres were useful in diverticular obliteration and preventing recurrence. Nevertheless, this is the first real-world large series reporting the advocated use of laser via both approaches for infundibulotomy as a surrogate to electrocautery in the past.

A recent systematic review by Ito et al. compared shockwave lithotripsy, RIRS and PCNL for single CD stones. Shockwave lithotripsy had the lowest SFR (21.3%) compared to RIRS (61.4%) and PCNL (83%) [12]. Of note, however, they included studies with inconsistent reporting of diverticula location, stones number, outcomes and complications. PCNL and RIRS have been further compared in small sample series [22, 23]; Ding et al. [22] compared mini-PCNL and RIRS and concluded a significant difference in SFR (90.5% vs 60%, p = 0.046). Bas et a l[23] also demonstrated, via a retrospective analysis of 54 patients, that symptom-free rates, success rates, SFR and RF were similar between the groups (p = 0.880, p = 0.537, p = 0.539 and p = 0.877 respectively), yet hospital stay was significantly longer for PCNL (3.86 ± 1.94 vs 1.04 ± 0.20 days; p < 0.001 for RIRS group). This is congruent with our study, where there is no significant difference in SFR in PCNL vs RIRS (71.5% vs 74%, p = 0.775), but longer hospital stay in PCNL group (p < 0.001, Table 1B).

Re-intervention rate by RIRS for RF > 4 mm was similar for both groups. UVA and MVA demonstrated that only multiple stones was a significant independent risk factor for poor SFR, not stone size. On UVA, the odds of RF are higher in lower pole CD (OR 0.474, 95% CI 0.226–0.956, p < 0.041). In particular, the choice of modality does not influence this outcome. In modern endourology, miniaturisation of both PCNL and RIRS make them equally effective, a concept reiterating findings proposed by Smyth et al. [9]. This demonstrates that as modern endourology evolves, evidence-based medicine is adapted to experience-based practise in different healthcare systems [24].

Nevertheless, PCNL efficacy must still be weighed against invasiveness and complication rates [12]. In a meta-analysis by Chang et al., PCNL for CD stones had significantly higher SFR (p = 0.004), but with more bleeding, longer hospital stay and higher overall complications than RIRS, and no significant difference in operative time [25]. Auge et al. compared 22 PCNL cases with 17 URS cases with a 78% SFR vs 19% for the latter, as well as a significantly higher SFR in upper pole CD for PCNL(p < 0.05), but higher complication rates [26]. In our study, although on-table inspection and formal SFR were higher in Group 1 than 2 (82.9% vs 75.6%), this was insignificant on eventual postoperative CT scan. All of our PCNL patients underwent mini-PCNL, and even though intraoperative bleeding was significantly higher in Group 1 (p < 0.032), no patients required postoperative transfusion.

Notably, any use of laser must be performed with caution. Two patients in Group 2 with malrotated kidneys sustained pelvicalyceal injures requiring transfusion, and one even required arterio-calyceal fistula embolization. Following PCNL, although rare, formation of intrarenal arteriovenous malformations has been reported up to 1.4%[27]. Arteriovenous malformations after RIRS with Holmium laser have also been reported by Bashar et al. [28], possibly attributed to mechanical injury from laser probe or guidewire during initial manipulation, or even thermal injury during stone fragmentation [29]. Inadvertent laser injury to the abnormal infundibular or arcuate vessel has been reported to cause arterio-calyceal fistula potentially requiring embolization [30].

There were no significant differences in intraoperative delineation and access to CD in PCNL or RIRS. In our cohort, failure to identify the ostium occurred in one patient in Group 1 and seven patients in Group 2, where conversion to ECIRS had to be performed. In total, ECIRS was used to facilitate surgery in 6 cases in Group 1 and 12 cases in Group 2—either for lithotripsy removal of stones or PCN placement. Lim et al. proposed that ECIRS can offer a personalised and tailored approach for all kidney stones [31]. This highlights that urologists should be flexible to alter their operative plan from RIRS to PCNL or ECIRS in cases of difficulty to minimise complications or further procedures.

In our study, PSM minimised selection bias and adjusted for the bias inherent to the different baseline patient characteristics such that we could collect data on stone size and number, diverticula location and complications. Yet, we acknowledge that the retrospective nature of our study has the inherent bias of reporting and recording. Data from 11 countries were anonymised and this limited subgroup analysis based on ethnic or geographic backgrounds. Information on PCNL tract size was unavailable, and therefore we could not conclude if this affected the SFR. Furthermore, the study also did not assess quality of life and symptomatic relief which are equally important in patient management. Finally, recurrence of CD and/or stones is one of the most interesting issues—to assess equivalence of PCNL vs RIRS was unfortunately not possible in our study, neither did we have sufficient data on stone composition to make deducible inferences, although these are very relevant in clinical practise.

Nevertheless, our multicenter real-world experience reflects how evidence from past practises is adopted and modified to achieve actual outcomes, so as to provide a better understanding of CD stone management. MVA shows that odds of having a higher SFR are only significant when managing a single stone, irrespective of the location. RIRS also has the best odds for lower pole CD stones, and significantly higher odds if the stone size is < 1 cm, irrespective of location. Whilst the odds of having a successful RIRS are higher for malrotated kidneys and multiple stones, it is not necessarily significantly better.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicentre PSM real-world comprehensive comparison of RIRS vs PCNL in CD stone management. Both the approaches are feasible and safe but clinicians can adopt a step-up personalised approach, and also discuss the potential of ECIRS for a tailored approach when needed, to optimise single-stage SFR. Laser infundibulotomy may be easily performed by either route and does not have major consequences in the immediate postoperative period. The long-term benefit of preventing recurrence and symptomatic relief could not be assessed.

Data availability

Not available.

References

Mullett R, Belfield JC, Vinjamuri S (2012) Calyceal Diverticulum - a Mimic of Different Pathologies on Multiple Imaging Modalities. J Radiol Case Rep 6(9):10–17

Waingankar N, Hayek S, Smith AD, Okeke Z (2014) Calyceal diverticula: a comprehensive review. Rev Urol 16(1):29–43

Turna B, Raza A, Moussa S, Smith G, Tolley DA (2007) Management of calyceal diverticular stones with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy: long-term outcome. BJU Int 100(1):151–156

Timmons JW, Malek RS, Hattery RR, Deweerd JH (1975) Caliceal diverticulum. J Urol 114(1):6–9

Gauhar V, Chew BH, Traxer O, Tailly T, Emiliani E, Inoue T et al (2023) Indications, preferences, global practice patterns and outcomes in retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) for renal stones in adults: results from a multicenter database of 6669 patients of the global FLEXible ureteroscopy Outcomes Registry (FLEXOR). World J Urol 41(2):567–574

Quiroz Y, Somani BK, Tanidir Y, Tekgul S, Silay S, Castellani D et al (2022) Retrograde intrarenal surgery in children: evolution, current status, and future trends. J Endourol 36(12):1511–1521

García Rojo E, Teoh JYC, Castellani D, Brime Menéndez R, Tanidir Y, Benedetto Galosi A et al (2022) Real-world global outcomes of retrograde intrarenal surgery in anomalous kidneys: a high volume international multicenter study. Urology 159:41–47

Lim EJ, Teoh JY, Fong KY, Emiliani E, Gadzhiev N, Gorelov D et al (2022) Propensity score-matched analysis comparing retrograde intrarenal surgery with percutaneous nephrolithotomy in anomalous kidneys. Minerva Urol Nephrol. https://doi.org/10.23736/S2724-6051.22.04664-X

Smyth N, Somani B, Rai B, Aboumarzouk OM (2019) Treatment options for calyceal diverticula. Curr Urol Rep 20(7):37

Canales B, Monga M (2003) Surgical management of the calyceal diverticulum. Curr Opin Urol 13(3):255–260

Skolarikos A, Jung H, Neisius A, Petřík A, Somani B, Tailly T, Gambaro G (2023) EAU guidelines on urolithiasis. Edn. In: Presented at the EAU Annual Congress Milan 2023 (ISBN 978-94-92671-19-6)

Ito H, Aboumarzouk OM, Abushamma F, Keeley FX (2018) Systematic review of caliceal diverticulum. J Endourol 32(10):961–972

Cohen TD, Preminger GM (1997) Management of calyceal calculi. Urol Clin North Am 24(1):81–96

Bellman GC, Silverstein JI, Blickensderfer S, Smith AD (1993) Technique and follow-up of percutaneous management of caliceal diverticula. Urology 42(1):21–25

Lechevallier E, Saussine C, Traxer O (2008) Management of stones in renal caliceal diverticula. Progres En Urol J Assoc Francaise Urol Soc Francaise Urol 18(12):989–991

Monga M, Smith R, Ferral H, Thomas R (2000) Percutaneous ablation of caliceal diverticulum: long-term follow-up. J Urol 163(1):28–32

Shalhav AL, Soble JJ, Nakada SY, Wolf JS, McClennan BL, Clayman RV (1998) Long-term outcome of caliceal diverticula following percutaneous endosurgical management. J Urol 160(5):1635–1639

Eshghi M, Tuong W, Fernandez R, Addonizio JC (1987) Percutaneous (Endo) infundibulotomy. J Endourol 1(2):107–114

Hulbert JC, Hernandez-Graulau JM, Hunter DW, Castañeda-Zuñiga WR (1988) Current concepts in the management of pyelocaliceal diverticula. J Endourol 2(1):11–17

Sah AK, Maharjan B, Adhikari MB (2021) Flexible ureteroscopic holmium laser infundibulotomy and lithotrypsy for the management of calyceal diverticular stone with infundibular atresia: a case report. Birat J Health Sci 6(3):1657–1660

Kim HL, Gerber GS (2000) Use of ureteroscopy and holmium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet laser in the treatment of an infundibular stenosis. Urology 55(1):129–131

Ding X, Xu ST, Huang YH, Wei XD, Zhang JL, Wang LL et al (2016) Management of symptomatic caliceal diverticular calculi: Minimally invasive percutaneous nephrolithotomy versus flexible ureterorenoscopy. Chronic Dis Transl Med 2(4):250–256

Bas O, Ozyuvali E, Aydogmus Y, Sener NC, Dede O, Ozgun S et al (2015) Management of calyceal diverticular calculi: a comparison of percutaneous nephrolithotomy and flexible ureterorenoscopy. Urolithiasis 43(2):155–161

Puljak L (2022) The difference between evidence-based medicine, evidence-based (clinical) practice, and evidence-based health care. J Clin Epidemiol 1(142):311–312

Chang X, Xu M, Ding L, Wang X, Du Y (2022) The clinical efficacy of percutaneous nephrolithotomy and flexible ureteroscopic lithotripsy in the treatment of calyceal diverticulum stones: a meta-analysis. Arch Esp Urol 75(5):423–429

Auge BK, Munver R, Kourambas J, Newman GE, Preminger GM (2002) Endoscopic management of symptomatic caliceal diverticula: a retrospective comparison of percutaneous nephrolithotripsy and ureteroscopy. J Endourol 16(8):557–563

Aboumarzouk OM, Somani BK, Monga M (2012) Flexible ureteroscopy and holmium:YAG laser lithotripsy for stone disease in patients with bleeding diathesis: a systematic review of the literature. Int Braz J Urol Off J Braz Soc Urol. 38(3):298–305 (discussion 306)

Bashar A, Hammad FT (2019) Intrarenal arteriovenous malformation following flexible ureterorenoscopy and holmium laser stone fragmentation: report of a case. BMC Urol 19(1):20

Tiplitsky SI, Milhoua PM, Patel MB, Minsky L, Hoenig DM (2007) Case report: intrarenal arteriovenous fistula after ureteroscopic stone extraction with holmium laser lithotripsy. J Endourol 21(5):530–532

Silva Simões Estrela JR, Azevedo Ziomkowski A, Dauster B, Costa Matos A (2020) Arteriocaliceal fistula: a life-threatening condition after retrograde intrarenal surgery. J Endourol Case Rep. 6(3):241–243

Lim EJ, Osther PJ, Valdivia Uría JG, Ibarluzea JG, Cracco CM, Scoffone CM, Gauhar V (2021) Personalized stone approach: can endoscopic combined intrarenal surgery pave the way to tailored management of urolithiasis? Minerva Urol Nephrol 73(4):428–430

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VG: project development, protocol development, manuscript editing. OT: data collection, data management. SJQW: manuscript writing, manuscript editing. KYF: data collection, data analysis. DR: data collection, data management, manuscript editing. AW: data collection, data management. SB: data collection, manuscript editing. AM: data collection, data management. MP: data collection. NG: data collection. YT: data collection. IGM: data collection, Data management. CA: protocol development, data collection. YB: data collection. BHS: data collection, data management. RBF: data management. MSM: data collection. TI: data collection, data management. JYCT: data collection. DC: data collection, data management. SB: protocol development, data collection. EJL: data analysis, protocol development, manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organisation&& or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This retrospective chart review study involving human participants was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Anonymized data used were maintained in the Human Investigation Committee (IRB) approved registry of global trends in PCNL and RIRS intervention for Calyceal Diverticulum, maintained by the by Asian Institute of Nephrology and Urology (AINU).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gauhar, V., Traxer, O., Woo, S.J.Q. et al. PCNL vs RIRS in management of stones in calyceal diverticulum: outcomes from a global multicentre match paired study that reflects real world practice. World J Urol 41, 2897–2904 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04650-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-023-04650-2