Abstract

Objective

To assess the outcome of low risk prostate cancer (PCa) patients who were candidates for active surveillance (AS) but had undergone robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP).

Method

We reviewed our prospectively collected database of patients operated by RARP between 2006 and 2014. Low D’Amico risk patients were selected. Oncological outcomes were reported based on pathology results and biochemical failure. Functional outcomes on continence and potency were reported at 12 and 24 months. Continence was assessed by the number of pads per day. With respect to potency, it was assessed using the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) and Erectile Hardness Scale (EHS).

Results

Out of 812 patients, 237 (29.2%) patients were D’Amico low risk and were eligible for analysis. 44 men fit Epstein’s criteria. 134 (56.5%) men had pathological upgrading. Age and clinical stage were predictors of upgrading on multivariate analysis. 220 (92.8%) patients had available follow-up for biochemical recurrence, potency, and continence for 2 years. The mean and median follow-up was 34.8 and 31.4 months, respectively. Only 5 (2.3%) men developed BCR, all of whom had pathological upgrading. Extra capsular extension and positive surgical margins were observed in 14.8 and 19.1%, respectively. 0 pad was achieved in 86.7 and 88.9% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. Proportion of patients with SHIM > 21 at 1 and 2 years was 24.8 and 30.6%, respectively. Moreover, patients having erections adequate for intercourse (EHS ≥ 3) were seen in 69.6 and 83.1% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. Functional outcomes of patients fitting Epstein’s criteria (n = 44) and patients with no upgrading on final pathology (n = 103) were not significantly different compared to the overall low risk study group.

Conclusion

This retrospective study showed that RARP is not without harm even in patients with low risk disease. On the other hand, considerable rate of upgrading was noted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is the only treatment for localized prostate cancer (PCa) that showed benefit in overall survival (OS) and cancer specific survival (CSS), compared with active surveillance (AS) [1,2,3].

Currently reported benefit of AS compared to active treatment is to avoid the risk of overtreatment specifically for very low risk and low-risk disease. The main advantage behind avoiding overtreatment is to prevent treatment complications, namely the risk of erectile dysfunction and incontinence. On the other hand, upgrading and/or upstaging are the main risks of AS compared to active treatment, but observed rates of cancer-specific mortality are indeed low [2]. The increasing usage of robots in radical prostatectomies has contributed to better functional outcomes [4]. Radical prostatectomy, witnessed a great amelioration throughout the years. Many techniques describing the preservation of pelvic floor integrity and the external sphincter mechanism have improved continence outcomes. Nerve sparing techniques have been playing a major role in potency as well as continence recovery. This has reduced the side effects related to radical prostatectomy, especially in low-risk patients where nerve-sparing techniques could be applied without interfering with cancer control and preserving at the same time potency and to a lesser extent continence.

This study analyzes the oncological and functional outcomes of low risk PCa patients eligible for AS who underwent RARP, the majority before AS era and the rest based on patients' choice, in order to examine if surgical treatment is devoid of harm from a functional point of view compared to AS. The ultimate goal being to achieve optimal cancer control without affecting functional outcomes.

Materials and methods

We queried our prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent RARP by two surgeons, between 2006 and 2015. Patients having D’Amico low risk PCa (PSA < 10, Gleason score ≤ 6, clinical stage ≤ T2a) [5] who were eligible for AS were selected. A subgroup of patients meeting Epstein’s criteria (PSA density < 0.15 ng/ml, Gleason score ≤ 6, clinical stage ≤ T1c, < 3 positive cores, < 50% cancer per core) [6] was also chosen. Oncological outcomes were measured by Gleason score upgrading, extra capsular extension (ECE), positive surgical margins (PSM), seminal vesical invasion (SVI), lymph node (LN) status, and biochemical recurrence (BCR). BCR was defined as two consecutive rises of PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/dl, or a PSA ≥ 0.4 ng/dl. Moreover, patients who received salvage external beam radiation therapy and/or androgen deprivation therapy were included in the BCR group [7]. Functional outcomes were examined at 1 and 2 years of follow-up at three levels: continence, potency, and functional lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Incontinence was measured by the number of pads needed in 24 h (0 pad, 1 security liner, 1 or more pads) at 1 and 2 years. Potency was evaluated using the Sexual Health Inventory for Men (SHIM) score, and the erectile hardness scale (EHS) by grouping together scores 3 and 4 which reflect erections hard enough for penetration. All patients had bilateral nerve sparing. Of note, erectile function was reported without taking into account if patients were on oral ED treatment due to the lack of information. International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) score with quality of life (QoL) questionnaire was used to evaluate LUTS.

Statistical analysis

SHIM, IPSS and QoL scores were compared to preoperative values by considering them as continuous variables and comparing their means by Student’s test. Predictors of Gleason upgrading were measured using a logistic regression model. All statistical tests were two-sided with a level of significance set at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using the R software environment for statistical computing and graphics (version 3.3.3; http://www.r-project.org/).

Results

Of 812 patients eligible for analysis, 237 (29.2%) low risk D’Amico patients met our inclusion criteria. Of those, 44 (18.6% of low risk patients) (5.4% of all patients) met Epstein’s criteria. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Oncological outcomes

Of the 237 individuals, 134 patients (56.5%) had pathological upgrading. Predictors of upgrading on multivariate analysis were advanced age and cT2a stage (Table 2).

Biochemical recurrence data were available for 220 (92.8%) patients. The mean and median follow-up was 34.8 and 31.4 months, respectively. In this group, 215 men were free of recurrence and 5 (2.3%) had BCR. Patients who recurred had a Gleason sum score of 7 on definitive pathology. With respect to patients meeting Epstein’s criteria, mean and median follow-up was 35 and 31 months, respectively. In this subgroup, we noted that 21 (47.7%) men had pathological upgrading (Table 3) but none had BCR.

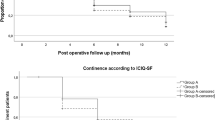

Continence

Continence rates were 86.7 and 88.9% at 1 and 2 years, respectively, using the 0 pad/24 h definition. When using the definition of 0 pad or 1 security liner, continence rates increased to 92.8 and 94.7% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. Only 2.8% of patients needed 2 pads or more at 1 year, and 2.6% at 2 years (Table 4).

Potency

Rates of EHS of 4 were 28.9 and 32.5% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. If we consider erections hard enough for penetration (EHS of 3 and 4), we found that the percentage increased to 55.6 and 64.3% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. If we exclude patients who had preoperative SHIM below 12, the percentage of EHS 3–4 increased to 61.9 and 73.3% at 1 and 2 years, respectively. These same values increase up to 64.5 and 75.9% at 1 and 2 years, respectively, if patients with a preoperative SHIM < 17 were excluded (Table 4).

Compared to preoperative score (mean = 19.72), SHIM was significantly lower at 1 year postoperatively (mean = 11.44, p < 0.001), and at 2 years (mean = 13.05, p < 0.001), respectively.

Functional urinary symptoms

Postoperative IPSS and QoL scores were significantly lower compared to preoperative values (Tables 4, 5, 6).

Discussion

In the present study we reported on the oncological and functional outcomes of low risk prostate cancer patients operated by RARP. Those patients were eligible for AS. Indeed, all patients included in this study had low-risk PCa (GS < 7, PSA < 10, cT < 2b). The Toronto group has pioneered active surveillance (AS) and supported AS in low and intermediate risk (PSA ≤ 20 ng/dl, cT ≤ 2b) patients but with a GS of 6 exclusively [8]. Despite using low risk criteria, our study detected a considerable rate of Gleason score upgrading (56.5%) and pathological upstaging to pT3 (15.25%). Moreover, 18.9% of the patients had PSM and 2.3% had BCR. The present study should be cautiously compared to larger series due the limited number of patients and the short follow-up period. In the PIVOT study, Wilt et al. [3] noted that the tumor was confined to the prostate in 65.8% of the low risk disease group, and the percentage of PSM was 19.1%. Despite these results, the PIVOT trial concluded that RP did not reduce prostate cancer mortality as compared to the observation group [3].

Furthermore, El Hajj et al. [9] found that 50% of the 625 patients who fulfilled the Prostate Cancer Research International Active Surveillance criteria, and who underwent radical prostatectomy, had adverse pathological outcomes. This same point was stressed by Vellekoop et al. [10] who reported that more than one-third (33–45%) of men meeting AS criteria had adverse pathology at RP. In Carlsson et al. [11] study, upgrading of Gleason score or upstaging to stage pT3 was present in 34% (115/333) of the cases, and surgical margins were positive in 16% (54/329). Moreover, BCR rate at 1 year was 2.4% (8/334).

In the Vellkoop et al. [10] study, predictors of adverse pathology were older age, higher prostate specific antigen (PSA), PSA density greater than 0.15 ng/ml/cm3, palpable disease (cT2) and extent of cancer greater than 4 mm on biopsy. In another cohort of 1753 patients, who met the AS criteria and underwent RP, PSA was the most important predictor for unfavorable pathological features [12]. This is in contradiction with our study, where age and clinical stage were shown to be statistically significant predictors of upgrading as mentioned in Table 2. The lack of PSA association could be the result of limited number of patient and low PSA level.

Upgrading, upstaging, and SM may be bad surrogates for OS and CSS. This would explain the high OS and CSS in clinical low risk patient population despite high rates of upgrading and upstaging. Klotz et al. [13] showed that 2.8 and 1.5% of patients on AS have developed metastatic disease and died from prostate cancer, respectively, over a follow-up period of 15 years. However, in the Goteborg trial the overall survival benefit was in favor of radical prostatectomy. Indeed radical prostatectomy did not improve CSS in low risk patient (RR 0.54, p = 0.17). However, radical prostatectomy was associated with less metastases (RR 0.4, p < 0.006) [14]. With a 23.2 years follow-up (median of 13.4 years), the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group Randomized clinical trial reported that mortality was substantially decreased in the RP group (56.1%) versus the watchful waiting (WW) group (68.9%) [15]. Of note, the ProtecT study with a 10 year follow-up showed that there was no significant difference in prostate cancer mortality; however, lower incidence of disease progression or metastases was eminent in the RP or radiation therapy (RT) groups compared to AS group [16].

We need to emphasize that incorporation of new imaging techniques, such as “mpMRI” and “Genetic panels”, is highly promising for selecting candidates eligible for AS. Indeed, a recent review by Druskin et al. [17] it was shown that MR has a role in both selecting patients eligible for AS, and monitoring patients who are under AS. “Genetic panels” are promising prediction tools that help select patients for AS and deciding whether to monitor or to actively treat [18,19,20,21].

Despite its good oncological outcomes, and high cure rate, RARP has its functional drawbacks. Wilt et al. [22] stated in his updated PIVOT trial that RP was associated with higher frequency of adverse events but a lower frequency of treatment related disease progression. RP had the greatest negative effect on urinary incontinence at 6 months, and the recovery remained worse in this group compared to AS and RT groups [23]. In the study by Carlsson et al. [11], 84% of patients were continent at 12 months when continence was defined as less than 1 pad per 24 h. When defined as pad free it dropped to 72%, and went down to 47.3% when using the definition of pad free and leakage free. According to Donovan et al. [24], 17% of the patients were still using pads 6 years after the surgery. In the current study, continence was defined as pad free. Rates of 0 pad were 87% at 12 months and 89% at 24 months. Our results compare favorably to the literature on continence post RARP. A systematic review done by Ficcara et al. [25] that discussed the continence recovery of all risk patients after RARP showed that the continence rate was 72%, 12 months after surgery. Wallerstedt et al. used the definition of < 1 pad and found a continence rate of 76% at 12 months post retropubic radical prostatectomy (RRP) or RARP. Moreover, in their trial, all risk category was taken into consideration [26]. It was shown that continence rates increased with the degree of nerve preservation [27]. This could explain our higher rates since all the patients underwent nerve prseservation. Severe incontinence is reported in less than 3%. Some of the risk factors associated with worse incontinence are older age, black race, and a high PSA score at diagnosis [28].

Additionally, IPSS and QoL improved after RARP despite the development of urinary incontinence. Moreover, the QoL score we used is dependent on urinary symptoms and is not affected by sexual complaints. Impotence could negatively impact the quality of life as well. The Scandinavian study stated that all men with localized prostate cancer reported a negative influence on their daily activities regardless of the treatment strategy [29].

According to Wilt et al. [22] a higher percentage of erectile and sexual dysfunction was noted in the surgical group. Moreover, in Donovan trial, it was found that at 6 months after surgery, only 12% of patients reported erections hard enough for intercourse. This value increases to 21% at 36 months and then back to 17% at 6 years [17, 24]. Similar results were reported in the Scandinavian study [29]. In a recent review of literature by Ficcarra et al. [30], the erectile function recovery was found to be 70% at 12 months. Definition varied between different studies from SHIM > 21 to erection sufficient for intercourse in more than 50% of times. In the study of Carlsson et al. [11], 15.6% had an IIEF score > 21 at 1 year and 36.9% had erection sufficient for intercourse in about half the time or above. Using the definition of erectile recovery of the LAPPRO trials, Hangling et al. showed a recovery of 25 to 30% at 1 year [31]. In our study, of patients with preoperative SHIM ≥ 17, 64.5 and 75.9% had an EHS ≥ 3 at 1 and 2 years, respectively. On the other hand only 36.6 and 42.3% of patients recovered a SHIM ≥ 17 at 1 and 2 years, respectively. Similarly, of patients with preoperative SHIM > 21, 69.6 and 83.1% had an EHS ≥ 3 at 1 and 2 years, respectively.

Another study on patients eligible for AS was conducted by Van der Bergh [32], where 14% of the men were sexually active without erectile problems at 18 months compared with 70% of the men in the group who had not undergone surgery. Mulhall et al. [33] showed that erectile dysfunction was higher in multicenter, multisurgeons’ trials compared to single center, single surgeon’s experience. This could partly explain our higher rates of sexual function recovery when measured by EHS.

Despite its merits, our study is limited by its retrospective design with a limited number of patients and short follow-up. It is also a single center experience. However, it is one of few studies that reported outcomes on patients eligible for AS and were operated by RARP. Another important drawback is that the majority of these patients did not undergo confirmatory biopsy or multiparametric MRI. Therefore, they do not represent a true AS cohort.

Conclusion

This retrospective study showed that RARP even for patients with low risk disease is not harmless. On the other hand, despite low BCR rate, considerable rates of upgrading, extra capsular extension (ECE), and PSM were also observed.

Abbreviations

- AS:

-

Active surveillance

- BCR:

-

Biochemical recurrence

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CSS:

-

Cancer specific survival

- EHS:

-

Erectile Hardness Scale

- ECE:

-

Extra capsular extension

- LUTS:

-

Lower urinary tract symptoms

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- PCa:

-

Prostate cancer

- PSM:

-

Positive surgical margin

- RARP:

-

Robot-assisted radical prostatectomy

- RP:

-

Radical prostatectomy

- RRP:

-

Retropubic radical prostatectomy

- RT:

-

Radiotherapy

- SHIM:

-

Sexual Health Inventory for Men

References

Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Filén F et al (2008) Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in localized prostate cancer: the Scandinavian prostate cancer group-4 randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 100:1144–1154. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn255

Andersson S-O, Andrén O, Lyth J et al (2011) Managing localized prostate cancer by radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: cost analysis of a randomized trial (SPCG-4). Scand J Urol Nephrol 45:177–183. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365599.2010.545075

Wilt TJ, Brawer MK, Jones KM et al (2012) Radical prostatectomy versus observation for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 367:203–213. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1113162

Kwon O, Hong S (2014) Active surveillance and surgery in localized prostate cancer. Minerva Urol E Nefrol Ital J Urol Nephrol 66:175–187

D’Amico AV, Whittington R, Malkowicz SB et al (1998) Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 280:969–974

Lee MC, Dong F, Stephenson AJ et al (2010) The Epstein criteria predict for organ-confined but not insignificant disease and a high likelihood of cure at radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 58:90–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2009.10.025

eau 2016 guidelines prostate cancer—Google Search. https://www.google.fr/#q=eau+2016+guidelines+prostate+cancer. Accessed 29 Oct 2016

Musunuru HB, Yamamoto T, Klotz L et al (2016) Active surveillance for intermediate risk prostate cancer: survival outcomes in the Sunnybrook experience. J Urol 196:1651–1658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2016.06.102

El Hajj A, Ploussard G, de la Taille A et al (2013) Analysis of outcomes after radical prostatectomy in patients eligible for active surveillance (PRIAS). BJU Int 111:53–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11276.x

Vellekoop A, Loeb S, Folkvaljon Y, Stattin P (2014) Population based study of predictors of adverse pathology among candidates for active surveillance with Gleason 6 prostate cancer. J Urol 191:350–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.034

Carlsson S, Jäderling F, Wallerstedt A et al (2016) Oncological and functional outcomes 1 year after radical prostatectomy for very-low-risk prostate cancer: results from the prospective LAPPRO trial. BJU Int 118:205–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/bju.13444

Mizuno K, Inoue T, Kinoshita H et al (2016) Evaluation of predictors of unfavorable pathological features in men eligible for active surveillance using radical prostatectomy specimens: a multi-institutional study. Jpn J Clin Oncol 46:1156–1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyw130

Klotz L, Vesprini D, Sethukavalan P et al (2015) Long-term follow-up of a large active surveillance cohort of patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 33:272–277. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1192

Godtman RA, Holmberg E, Khatami A et al (2013) Outcome following active surveillance of men with screen-detected prostate cancer. Results from the Göteborg randomised population-based prostate cancer screening trial. Eur Urol 63:101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.08.066

Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H et al (2014) Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 370:932–942. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1311593

Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA et al (2016) 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1415–1424. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606220

Druskin SC, Macura KJ (2018) MR imaging for prostate cancer screening and active surveillance. Radiol Clin N Am 56:251–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2017.10.006

Cuzick J, Berney DM, Fisher G et al (2012) Prognostic value of a cell cycle progression signature for prostate cancer death in a conservatively managed needle biopsy cohort. Br J Cancer 106:1095–1099. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.39

Crawford ED, Scholz MC, Kar AJ et al (2014) Cell cycle progression score and treatment decisions in prostate cancer: results from an ongoing registry. Curr Med Res Opin 30:1025–1031. https://doi.org/10.1185/03007995.2014.899208

Klein EA, Cooperberg MR, Magi-Galluzzi C et al (2014) A 17-gene assay to predict prostate cancer aggressiveness in the context of Gleason grade heterogeneity, tumor multifocality, and biopsy undersampling. Eur Urol 66:550–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.05.004

Cullen J, Rosner IL, Brand TC et al (2015) A biopsy-based 17-gene genomic prostate score predicts recurrence after radical prostatectomy and adverse surgical pathology in a racially diverse population of men with clinically low- and intermediate-risk prostate cancer. Eur Urol 68:123–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.11.030

Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ et al (2017) Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 377:132–142. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1615869

Donovan MJ, Cordon-Cardo C (2014) Genomic analysis in active surveillance: predicting high-risk disease using tissue biomarkers. Curr Opin Urol 24:303–310. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0000000000000051

Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Lane JA et al (2016) Patient-reported outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 375:1425–1437. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1606221

Ficarra V, Novara G, Rosen RC et al (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting urinary continence recovery after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 62:405–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.045

Wallerstedt A, Carlsson S, Steineck G et al (2013) Patient and tumour-related factors for prediction of urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy. Scand J Urol 47:272–281. https://doi.org/10.3109/00365599.2012.733410

Steineck G, Bjartell A, Hugosson J et al (2015) Degree of preservation of the neurovascular bundles during radical prostatectomy and urinary continence 1 year after surgery. Eur Urol 67:559–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.011

Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J et al (2008) Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med 358:1250–1261. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa074311

Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Holmberg L et al (2013) Long-term distress after radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in prostate cancer: a longitudinal study from the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomized clinical trial. Eur Urol 64:920–928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.02.025

Ficarra V, Novara G, Ahlering TE et al (2012) Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting potency rates after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Eur Urol 62:418–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2012.05.046

Haglind E, Carlsson S, Stranne J et al (2015) Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction after robotic versus open radical prostatectomy: a prospective, controlled, nonrandomised trial. Eur Urol 68:216–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.02.029

Van den Bergh RCN, Korfage IJ, Roobol MJ et al (2012) Sexual function with localized prostate cancer: active surveillance vs radical therapy. BJU Int 110:1032–1039. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10846.x

Mulhall JP (2009) Defining and reporting erectile function outcomes after radical prostatectomy: challenges and misconceptions. J Urol 181:462–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.047

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zanaty, M., Ajib, K., Zorn, K. et al. Functional outcomes of robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in patients eligible for active surveillance. World J Urol 36, 1391–1397 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2298-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-018-2298-3