Abstract

Purpose

In recent times there has been a trend in mininvasive renal tumour surgery. Very limited evidence can be found in literature of the outcomes of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) for highly complex renal tumours. The aim of the present study was to assess the feasibility and safety of LPN for renal tumours of high surgical complexity in our single-institutional experience, comparing perioperative and functional data between clampless and clamped procedures.

Materials and methods

We enrolled 68 patient who underwent a clampless LPN (Group A) and 41 patients who underwent a clamped LPN (Group B) for a renal tumour with a R.E.N.A.L. NS ≥ 10. Intraoperative and post-operative complications have been classified and reported according to international criteria. Kidney function was evaluated by measuring serum creatinine concentration and eGFR.

Results

Group A was found to be similar to Group B in all variables measured except for WIT (P = 0) and blood loss (P = 0.0188). In group A the mean creatinine levels were not significantly increased at the third post-operative (P = 0.0555) day and at the 6-month follow-up (P = 0.3047). Otherwise, in the group B the creatinine levels were significantly increased after surgery (P = 0.0263), but decreased over time, showing no significant differences at 6 month follow-up (P = 0.7985) compared to preoperative values. The same trend was seen for eGFR. Optimal Trifecta outcomes were achieved in both groups.

Conclusions

Clampless LPN represents a feasible and safe procedure, even for tumours with high surgical complexity, in highly experienced laparoscopic centers. When compared to clamped LPN, it results in better preservation of immediate post-operative renal function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent times, there has been a trend towards parenchymal sparing in renal tumour surgery through the employment of the minimally invasive approach. The exact size and location of renal tumours suitable for this type of surgery is currently under discussion. At present, partial nephrectomy (PN) is the “gold standard” treatment for organ-confined renal tumours when technically feasible, resulting in the same oncological outcomes as radical nephrectomy for small renal tumours (<4 cm) [1, 2]. The limit for PN is commonly considered 7 cm for the maximum diameter of tumour whenever feasible [3]. However, very limited evidence can be found in literature of the perioperative and functional outcomes of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) for highly complex renal tumours.

Today, however, the growing use of robot-assisted renal surgery has allowed for a greater number of cases to be potentially performed by a minimally invasive approach [4, 5].

Whatever the surgical technique used, the complications and outcomes of PN are associated with the treatment centre’s case volume and the surgeon’s learning curve [6, 7] which correlates with the anatomical features of each case.

To clamp or not to clamp has always been a topic that has sparked off considerable debate.

Thompson et al. [8] demonstrated that “every minute counts” when the renal hilum is clamped and that warm ischaemia time (WIT) is a well-known predictor of the post-operative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Given this restriction, it is advisable to perform a clampless PN whenever feasible, particularly in patients with poor baseline renal function [9]. The aim of the present study was to assess the feasibility and safety of LPN for renal tumours of high surgical complexity in our single-institutional experience, comparing perioperative and functional data between clampless and clamped procedures.

Patients and methods

Between January 2008 and July 2015, 486 LPN were performed at our institution. Out of 486 patients, 109 with high tumour complexity were selected. We used R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry scores [10] for assessing tumour complexity. Patients were evaluated preoperatively with renal ultrasonography (US) and a CT scan (CT). All procedures were performed by a single surgical team.

Intraoperative and post-operative complications have been classified and reported according to Satava [11] and Clavien–Dindo system [12].

We report qualitative outcomes of our surgical series based on the achievement of the TRIFECTA outcome (combination of warm ischaemia time (WIT) ≤25 min, no positive surgical margin and complications ≤Clavien grade 2 [13, 14]).

Kidney function was evaluated by measuring serum creatinine concentration and eGFR preoperatively, on the third post-operative day and 6 months following LPN. eGFR was calculated using the modification of diet renal disease (MDRD) equation [15].

Follow-up was appointed from the date of surgery to the date of the most recent documented examination. A physical examination and US were performed on all patients at 3 months, followed by a US or CT at the 6 month follow-up and then during the first 5 years after surgery according to patient risk profile [16].

Surgical procedure

The patient was positioned in lateral decubitus. Initial trans-peritoneal access was made through an open Hasson approach using a Hasson cannula. A 0° telescopic and two multi-disposal metal trocars (1 × 10−11 mm, 1 × 5 mm) were used. Dissection was carried out by using monopolar scissors and bipolar forceps. The bowel was mobilized medially, and Gerota’s fascia was opened. In 68 patients a clampless LPN after careful isolation and preparation of the renal pedicle was performed. In the remaining 41 cases, transient clamping of the main or polar arterial branch was performed by applying a bulldog clamp, before proceeding with tumour enucleation.

In all cases, a simple tumour enucleation without a layer of normal parenchyma was performed. Eventual bleeding was controlled by using a bipolar dissector, and complete hemostasis was achieved with the help of “FloSeal® hemostatic matrix” (Baxter Healthcare Corporation Fremont, USA). When necessary, a sliding hem-o-lok® clips (Teleflex Medical, Research Triangle Park, NC) absorbable suture was used for better hemostasis and kidney reconstruction.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics of categorical variables focused on frequencies and proportions. Means and standard deviation were reported for continuously coded variables. Chi-square and Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare the statistical significance of differences in proportions and means, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), considering a statistical significance at P < 0.05.

Results

According to R.E.N.A.L. NS, out of the total 486 LPN patients, 109 presented with high tumour complexity (score 10–12). Group A included 68 patients who underwent clampless LPN, and Group B included 41 patients who received clamped LPN. Table 1 depicts patients’ demographics and baseline characteristics. The two groups showed no difference in terms of patients’ demographics as well as tumour characteristics in all variables. Furthermore, no difference was detected in terms of preoperative baseline creatinine level (0.9 ± 0.5 and 1 ± 0.2, respectively, P = 0.2247) and preoperative baseline eGFR (85.7 ± 12.9 and 89.8 ± 10.8, respectively, P = 0.0910).

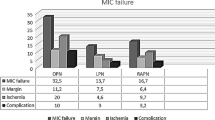

Table 2 summarizes the operative data. All operations were performed laparoscopically with a trans-peritoneal approach, and conversion to open surgery was required in no case. The Foley catheter was removed post-operatively on day 2 or 3. In only four cases, the catheter was left in place for a longer period (one case of haematuria and one of urinoma in group A; one case of haematuria and one of urinary tract infection in the group B). Group A was found to be similar to group B in terms of intraoperative variables except for WIT (P = 0.0) and blood loss (P = 0.0188). With regards to functional outcomes, in group A, the mean serum creatinine levels were not significantly increased at the third post-operative day (1.05 ± 0.4 mg/dL; P = 0.0555), and at the 6-month follow-up (0.98 ± 0.4 mg/dL; P = 0.3047) compared to the preoperative values. The same trend was seen for mean eGFR at the third post-operative day (81.5 ± 13.7 mL/min/1.73 m; P = 0.0679) and at 6-month follow-up (82.8 ± 13.4 mL/min/1.73 m; P = 0.2008). In group B, the mean serum creatinine levels were significantly increased after surgery (1.1 ± 0.2 mg/dL; P = 0.0263) compared to the preoperative values, but decreased over time, showing no significant increase at the 6-month follow-up (0.99 ± 0.15 mg/dL; P = 0.7985). Similar results were reported for eGFR at the third post-operative day (81.2 ± 9.7 mL/min/1.73 m; P = 0.0003) and at 6-month follow-up (87.4 ± 9.7 mL/min/1.73 m; P = 0.2930). Finally, Trifecta outcome was achieved in 64 patients (94 %) in group A and in 37 patients (90 %) in group B (P = 0.4525).

As shown in Table 2, two patients (2.9 %) of group A and one patient (2.4 %) of group B (P = 0.8766) presented positive surgical margins (PSMs). However, no present local and/or systemic tumour recurrence took place during the follow-up period.

Table 3 reports intra-operative and post-operative complications according to Satava and Clavien–Dindo systems. No significant differences between the two groups in terms of intraoperative (P = 0.5957) and post-operative complications (P = 0.4505) were detected.

Discussion

Our results indicate that LPN is a feasible and safe procedure in experienced hands in cases of tumours of high surgical complexity, regardless of whether performed with a clampless or clamped approach. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that reports detailed intraoperative and post-operative complications classified in accordance with international criteria and functional outcomes on a large series of LPN for renal tumours of high surgical complexity. Furthermore, it included a comparison between a clampless and clamped approach in terms of operative and functional outcomes.

It has been previously described that clampless LPN is a valid option in patients with larger, more complex renal tumours without compromising the perioperative outcomes in high experienced hands [17].

Robotic technology appears to allow a safer and more precise excision of complex renal tumours with a technique that has a shorter learning curve and offers technical advantages over classical laparoscopy [5]. As a consequence, many hospitals have shifted from the open PN to the robotic assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN). In the present robotic era, it is worth highlighting the feasibility and safety of LPN procedures on very complex tumours in highly experienced laparoscopic centres when robotic devices are not available. Furthermore, most recent European Association of Urology Guideline states that there is no difference in progression free survival and overall survival comparing LPN and open PN in centres with laparoscopic expertise [18, 19].

Current evidence suggests that the amount of residual functional parenchyma after PN represents a significant surgical factor that impacts on post-operative renal function [9, 20] and that warm ischaemia time (WIT) is a well-known predictor of post-operative eGFR [9]. Given these findings, it would be advisable to perform a clampless partial nephrectomy removing the danger risk of sacrificing healthy parenchyma.

Moreover, whenever feasible, at our institute a simple enucleation is performed, that has been described as a safe technique [21] with oncologic equivalence to standard partial nephrectomy [22].

The average length of stay, positive margins, and estimated blood loss are in line with previously reported experiences for all R.E.N.A.L. score tumours for both techniques (clamped and clampless) [23], except for the mean operative time that was shorter than the other series. The overall post-operative complication rate was similar for both groups A and B to the previous series in which both clamped and clampless LPNs were enrolled. There are few studies that analyse perioperative and functional outcomes of classical laparoscopic partial nephrectomy of a high complexity. In particular, no study selectively focuses on very high-risk neoplasms except for Volpe’s study that included RAPN with a PADUA score ≥10 [24]. White et al. [25] showed an increase of some parameters (warm ischaemia time, blood loss, and complications) in patients with moderately or highly complex renal masses who had undergone RAPN. Nevertheless their study included only 11 patients with a R.E.N.A.L. score ≥10. Moreover, Tanagho et al. [26] showed a correlation between R.E.N.A.L. score and perioperative complications. In particular, in the subgroup of patients with R.E.N.A.L. score ≥10, the intraoperative complication rate was 8.2 % and the post-operative complication rate was 23 %. In our series, we report an intraoperative complication rate of 4.4 and of 2.4 % in group A and in group B, respectively. Furthermore, 16.2 % of group A patients and 22 % of group B patients experienced post-operative complications. Group A was found to be similar to the group B in all intraoperative and post-operative variables except for a longer WIT and more abundant blood loss. In group A we found no significant differences in terms of eGFR and serum creatinine levels either in the immediate post-operative period or at 6-month follow-up. This positive functional data can be easily explained by the use of a clampless technique [9]. Conversely, in group B a transient post-operative deterioration of functional outcome was detected, showing a significant increase in serum creatinine levels and decrease in eGFR at the third day follow-up. However, a progressive improvement of functional outcome was detected over time, with no significant differences at a 6-month follow-up. The results that we detected in the clamped group are similar to those reported in a clinical study that included RAPN with a PADUA score ≥10, with cases showing a comparable WIT [24].

The results of our series highlight the feasibility and safety of LPN even in complex renal tumours, which should be considered a viable surgical option when robotic devices are not available, especially in centres with high laparoscopic expertise. Both clamped and clampless techniques allow the operator to achieve good functional results at a short 6-month follow-up, even if larger prospective studies with longer follow-up are needed to definitively compare the two approaches. Furthermore, it is well known that the laparoscopic approach leads to reduced costs compared to the robotic procedure [27], although the lack of an equal comparison in terms of direct and indirect costs prevented us from concluding which could be considered the optimal approach.

Trifecta was achieved in 64 (94 %) and 37 (90 %) of group A and group B patients, respectively (P = 0.4525). In the most recent era of zero ischaemia PN, trifecta was reached in 63–82 % of patients depending on the definitions that were applied [28]. The high rate of Trifecta achievement in both groups can be explained by the fact that all procedures were performed by a well trained and very experienced laparoscopic surgical team. Moreover, if we analyse Trifecta outcomes including all intraoperative and post-operative complications [29], Trifecta was obtained in 54 patients (79 %) in the group A and in 29 patients (71 %) in the group B (P = 0.3030).

Some limitations of the study herein include, firstly, the small cohort of patients and short follow-up time. Another limitation is that all procedures were performed by a single surgical team with significant expertise in laparoscopic surgery which may restrict the applicability of our results to centres with more limited laparoscopic experience. Furthermore we present only short-term functional data. Although our data was collected in a prospectively maintained database, a selection bias cannot be excluded. Moreover, this study is limited by its retrospective nature. Finally, the MDRD equation has limitations for eGFR evaluation [30] and although total renal function was preserved, we cannot include an accurate evaluation of post-operative ipsilateral renal function change due to the small number of patients who underwent a renal scan.

Conclusion

LPN represents a feasible and safe procedure for renal tumours of a high surgical complexity if performed in highly experienced laparoscopic centres. The procedure offers a low rate of intraoperative and post-operative complications and good preservation of renal function at short-term follow-up, regardless of a clampless or clamped approach. When compared to clamped LPN, clampless LPN results in better preservation of immediate post-operative renal function.

References

MacLennan S, Imamura M, Lapitan MC et al (2012) Systematic review of oncological outcomes following surgical management of localized renal cancer. Eur Urol 61:972–993

Ljungberg B, Cowan NC, Hanbury DC et al (2010) EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: the 2010 update. Eur Urol 58:398–406

Simmons MN, Weight CJ, Gill IS (2009) Laparoscopic radical versus partial nephrectomy for tumors >4 cm: intermediate-term oncologic and functional outcomes. Urology 73(5):1077–1082

Hanzly M, Frederick A, Creighton T, Atwood K, Mehedint D, Kauffman EC, Kim HL, Schwaab T (2015) Learning curves for robot-assisted and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. J Endourol 29(3):297–303

Pierorazio PM, Patel HD, Feng T, Yohannan J, Hyams ES, Allaf ME (2011) Robotic-assisted versus traditional laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: comparison of outcomes and evaluation of learning curve. Urology 78:813–819

Osaka K, Makiyama K, Nakaigawa N, Yao M (2015) Predictors of trifecta outcomes in laparoscopic partial nephrectomy for clinical T1a renal masses. Int J Urol. 22(11):1000–1005

Porpiglia F, Bertolo R, Amparore D, Fiori C (2013) Margins, ischaemia and complications rate after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: impact of learning curve and tumour anatomical characteristics. BJU Int 112(8):1125–1132

Thompson RH, Lane BR, Lohse CM, Leibovich BC, Fergany A, Frank I, Gill IS, Blute ML, Campbell SC (2010) Every minute counts when the renal hilum is clamped during partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol 58(3):340–345

Porpiglia F, Bertolo R, Amparore D, Podio V, Angusti T, Veltri A, Fiori C (2015) Evaluation of functional outcomes after laparoscopic partial nephrectomy using renal scintigraphy: clamped vs clampless technique. BJU Int 115(4):606–612

Kutikov A, Uzzo RG (2009) The R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score: a comprehensive standardized system for quantitating renal tumor size, location and depth. J Urol 182(3):844–853

Kazaryan AM, Røsok BI, Edwin B (2013) Morbidity assessment in surgery: refinement proposal based on a concept of perioperative adverse events. ISRN Surg 16(2013):625093

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D et al (2009) The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg 250(2):187–196

Carneiro A, Sivaraman A, Sanchez-Salas R, Di Trapani E et al (2015) Evolution from laparoscopic to robotic nephron sparing surgery: a high -volume laparoscopic center experience on achieving ‘trifecta’ outcomes. World J Urol 33(12):2039–2044

Hung AJ, Cai J, Simmons MN et al (2012) “Trifecta” in partial nephrectomy. J Urol 189:36–42

Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T et al (2006) Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 145(4):247–254

Skolarikos A, Alivizatos G, Laguna P et al (2007) A review on follow-up strategies for renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. Eur Urol 51(6):1490–1500

Rais-Bahrami S, George AK, Herati AS et al (2012) Off-clamp versus complete hilar control laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: comparison by clinical stage. BJU Int 109(9):1376–1381

Gill IS, Kavoussi LR, Lane BR et al (2007) Comparison of 1800 laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomies for single renal tumors. J Urol 178(1):41–46

Marszalek M, Meixl H, Polajnar M et al (2009) Laparoscopic and open partial nephrectomy: a matched pair comparison of 200 Patients. Eur Urol 55(5):1171–1178

Volpe A, Blute ML, Ficarra V, Gill IS, Kutikov A, Porpiglia F, Rogers C, Touijer KA, Van Poppel H, Thompson RH (2015) Renal ischemia and function after partial nephrectomy: a collaborative review of the literature. Eur Urol 68(1):61–74

Longo N, Minervini A, Antonelli A et al (2014) Simple enucleation versus standard partial nephrectomy for clinical T1 renal masses: perioperative outcomes based on a matched-pair comparison of 396 patients (RECORd project). Eur J Surg Oncol 40(6):762–768

Minervini A, Ficarra V, Rocco F et al (2011) Simple enucleation is equivalent to traditional partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: results of a nonrandomized, retrospective, comparative study. J Urol 185:1604–1610

Choi JE, You JH, Kim DK, Rha KH, Lee SH (2015) Comparison of perioperative outcomes between robotic and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 67(5):891–901

Volpe A, Garrou D, Amparore D, De Naeyer G, Porpiglia F, Ficarra V, Mottrie A (2014) Perioperative and renal functional outcomes of elective robot-assisted partial nephrectomy (RAPN) for renal tumours with high surgical complexity. BJU Int 114(6):903–909

White MA, Haber GP, Autorino R, Khanna R, Hernandez AV, Forest S, Yang B, Altunrende F, Stein RJ, Kaouk JH (2011) Outcomes of robotic partial nephrectomy for renal masses with nephrometry score of ≥7. Urology 77(4):809–813

Tanagho YS, Kaouk JH, Allaf ME, Rogers CG, Stifelman MD, Kaczmarek BF, Hillyer SP, Mullins JK, Chiu Y, Bhayani SB (2013) Perioperative complications of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: analysis of 886 patients at 5 United States centers. Urology. 81(3):573–579

Buse S, Hach CE, Klumpen P, Alexandrov A, Mager R, Mottrie A, Haferkamp A (2015) Cost-effectiveness of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy for the prevention of perioperative complications. World J Urol. doi:10.1007/s00345-015-1742-x

Takagi T, Mir MC, Campbell RA, Sharma N, Remer EM, Li J, Demirjian S, Kaouk JH, Campbell SC (2014) Assessment of outcomes in partial nephrectomy incorporating detailed functional analysis. Urology 84(5):1128–1133

Khalifeh A, Autorino R, Hillyer SP, Laydner H, Eyraud R, Panumatrassamee K, Long JA, Kaouk JH (2013) Comparative outcomes and assessment of trifecta in 500 robotic and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy cases: a single surgeon experience. J Urol 189(4):1236–1242

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH et al (2009) A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150:604–612

Acknowledgments

Juliet Ippolito, B.A. Vassar College, MPhil University of Dundee for English language editing.

Authors contribution

P. Verze was involved in protocol/project development, manuscript writing/editing, and data collection or management; P. Fedelini was involved in protocol/project development and data collection or management; F. Chiancone performed manuscript writing/editing, protocol/project development, data collection or management, and data analysis; V. Cucchiara contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing/editing; R. La Rocca was involved in data analysis; M. Fedelini and C. Meccariello performed data collection or management; A. Palmieri and V. Mirone were involved in protocol/project development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.ACKNOWLEDGMENT Juliet Ippolito, B.A. Vassar College, MPhil University of Dundee for English language editing

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Verze, P., Fedelini, P., Chiancone, F. et al. Perioperative and renal functional outcomes of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy (LPN) for renal tumours of high surgical complexity: a single-institute comparison between clampless and clamped procedures. World J Urol 35, 403–409 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-016-1882-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-016-1882-7