Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review is to describe the scientific evidence regarding sonographic findings of joints in SLE patients.

Methods

Seven databases were searched (PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Cochrane, EMBASE, LILACS, and SciELO) for articles from 1950 to January 2015. The keywords used for selecting articles include “lupus”, “ultrasound imaging”, “ultrasonography”, “synovitis”, “tenosynovitis”, and “arthritis”.

Results

A total of 12 articles were included in the final analysis. In total, 610 SLE patients and 1,091 joints were studied. Most patients underwent bilateral joint examination by US. A total of 888 hands and wrists, 154 ankles/feet, and 56 knees were examined. Effusion was identified in 602 joints, synovitis in 213, tenosynovitis in 210, synovial hypertrophy in 150, and bone erosions in 73 cases. The majority of the studies demonstrated higher frequency of musculoskeletal abnormalities on US than those observed on physical examination.

Conclusion

US seems to be a valuable tool to identify subclinical joint manifestations in SLE. Prospective studies are necessary to determine if those patients with subclinical joint abnormalities have a higher risk for the development of chronic deformities as those seen in Jaccoud’s Arthropathy.

Key Points

• Musculoskeletal involvement occurs in more than 90 % of SLE cases.

• Arthralgia or tender/swollen joints found on physical examination showed more US findings.

• Patients without joint symptoms or physical examinations changes showed musculoskeletal sonographic findings.

• US became a useful tool for rheumatologists.

• A substantial number of asymptomatic patients show abnormalities at musculoskeletal US.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic autoimmune, inflammatory, multisystemic disease of unknown cause. Musculoskeletal involvement occurs in more than 90 % of the cases and can be related to the disease itself or to its treatment; arthralgia/arthritis being the most common manifestation [1]. In general, it responds promptly to the treatment, and only about 5 % of the patients develop chronic deforming arthropathy, named Jaccoud’s Arthropathy (JA) [2].

Some examples of the role of imaging techniques in the evaluation of the musculoskeletal manifestation of SLE are the absence of joint erosions on plain radiographs and the identification of avascular necrosis induced by corticosteroids by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [3–5]. Ultrasound (US) is a noninvasive diagnostic procedure with a good accuracy in the detection of joint effusion, evaluation of integrity of tendons and muscles, soft tissue swelling, and visualization of cartilage/bone surface [6, 7]. The main advantage of the US lies on its ability to detect these findings even on subclinical stage.

In some rheumatic disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA), US criteria are well defined, a fact that is not well established in SLE yet. This systematic review of the literature aims to describe the scientific evidence regarding the sonographic findings of joints in SLE patients.

Methods

This study was performed according to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [8].

Databases and research strategies

The search was conducted in seven databases (PubMed, ScienceDirect, Scopus, Cochrane, EMBASE, LILACS, and SciELO), including the so-called gray literature, from 1950 to January 2015. There was no language restriction. The research strategy used was: Search #2 (“Systemic Lupus Erythematosus” [MeSH Terms] OR “Lupus Erythematosus Disseminatus” [MeSH Terms] C17.300.480, C20.111.590; Search #3 ("ultrasound imaging" [MeSH Terms]) OR "Sonography" [MeSH Terms] OR “Ultrasonography” [MeSH Terms]) E01.370.350.850; Search #6 ("synovitis" [MeSH Terms]) C05.550.870; Search #7 ("tenosynovitis" [MeSH Terms]) C05.651.869.870; Search #8 ("arthritis" [MeSH Terms]) C05.550.114. Duplicate citations were excluded from the research.

Selection criteria and data extraction

Only articles related to SLE patients who underwent US of joints were selected for this research. The inclusion criteria were: 1) Studies with enough available information regarding ultrasonographic, clinical and laboratorial findings; 2) Studies that evaluated synovial hypertrophy, joint effusion, tenosynovitis, and bone erosion by US and these findings were associated with clinical and laboratorial parameters. Case reports, review articles, and studies including patients with more than one diffuse connective tissue disease (DCTD) were excluded.

Results

Forty-two articles fulfilled the initial keywords at databases search. From those 42, 25 studies were excluded after reading abstracts because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 17 articles were read by the authors, and five were excluded because they were case reports, review articles, and one was on monitoring after drug treatment. Thus, only 12 articles were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

In total, 610 SLE patients were studied, of which 527 were women. The mean age of the patients was 39 years (±7.7 years). One of the articles was on juvenile SLE patients [3], with a mean age of 15.8 years (±2.9 years) [3]. The duration of the disease at the time of the US ranged from 3.7 years to 17 years, with a mean of 11.2 years (±3.7 years). As one of the articles [9] did not indicate the duration of the disease, this information was calculated only with 11 studies (Table 1).

In half of the studies, the joints were examined bilaterally by US (six of 12). A total of 1,124 joints were examined: 888 hands and wrists, 154 ankles/feet, 56 knees, and 26 elbows. There were 602/1,124 (53.5 %) joints with effusion, 213/1,124 (18.9 %) with synovitis, 210/1,124 (18.7 %) with tenosynovitis, 150/1,124 (13.3 %) with synovial hypertrophy, and 73/1,124 (6.5 %) with bone erosions. Eleven out of 12 articles included mainly patients with articular symptoms or joint findings at physical examination. Only one study exclusively evaluated patients without joint manifestation [10].

The articles demonstrated that the patients with arthralgia or tender/swollen joints by physical examination had more US findings as synovitis than those without symptoms. For example, Iagnocco et al. [11] noted that patients with articular symptoms had more radioulnocarpal and metacarpophalangeal joint changes and higher inflammatory score by US than those without it. Similar results were reported by Dreyer et al. [9] as they found that wrist and metacarpophalangeal synovitis were statistically significant more frequent in patients with arthralgia than in those without it: wrist synovitis was detected by US in 16 SLE patients (81 %) with arthralgia compared to 17 patients without (18 %) (p = 0.0005) and 63 % had involvement of a metacarpophalangeal joint in the arthralgia group, but only 16 % in the asymptomatic group.

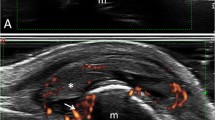

Gabba et al. [12] showed that patients with clinical manifestations had US and power Doppler changes mainly at joints, while asymptomatic individuals had more sonographic changes in tendons. All patients with arthritis on physical examination had pathology findings by US (13/13 – 100 %); 20 out of 26 (76.9 %) patients with only arthralgia had US changes (50 % of these were tendon synovial effusion) and 34 out of 69 (49.2 %) asymptomatic patients also had US alterations (29 % were tendon synovial effusion). Torrente-Segarra et al. [13] considered those patients who presented with arthralgia and normal physical examination, in addition to US changes and laboratory parameters of active disease, as having active subclinical disease.

The majority of the articles observed that many patients without joint symptoms or changes on physical examination showed sonographic findings on joints/tendons [3, 9–11, 14–17]. Iagnocco et al. [11] showed that only 40 % of their patients (25/62) had clinical features of joint involvement in SLE, while the majority of the patients (87.1 %) had US abnormalities. Yoon et al. [10] also demonstrated subclinical synovitis in 28/48 (58.3 %) of their patients, i.e., US alterations without symptoms or findings on physical examination. Accordingly, Ossandon et al. [15] described that US was able to detect joint inflammatory findings in 14 patients (37.8 %) who had normal physical examination of the joints. A recent study [17] reported that of 28 patients with inflammatory arthralgia and morning stiffness, 20 had at least one abnormality at US examination (either synovitis or tendon involvement). On the other hand, they observed that from 56 patients with US abnormalities, only 22 had joint finding at clinical examination, revealing the possibility of subclinical disease.

Six out of 12 studies showed the dissociation between disease activity, either clinical or laboratorial, and US findings [3, 11, 14–16, 18]. The laboratorial evaluation included C-reactive protein (CRP) obtained in 565 participants, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) performed in 478 patients, and levels of C3 and C4 tested in 523 and 446 patients, respectively. Autoantibodies, particularly anti-dsDNA antibodies, were evaluated in most studies, and a total of 558 patients were tested.

On the other hand, one study, Ball et al. [19], demonstrated that the plasma level of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) was associated with sonographic findings of synovitis [19]. Yoon et al. [10] showed a positive correlation between the US score and increased ESR and anti-dsDNA antibodies levels. Gabba et al. [12] observed that those individuals with lower serum levels of C3 and C4 were more likely to have musculoskeletal US abnormalities.

Discussion

US became a useful tool for rheumatologists as it can be used for diagnosis, monitoring treatment, and identification of complications, particularly in patients with RA. In recent years, such technique has also been studied in SLE patients as presented above.

One of the most difficult issues in the interpretation of the findings from the studies on US in SLE is the lack of standardization in sonographic techniques as well as the power Doppler features because the studies used different equipment. The ultrasound transducers used in these studies had a frequency varying from 5 to 18 MHz. It may have contributed to the lower frequency of tendon and joint abnormalities. It is well known that musculoskeletal US with higher-frequency transducers (13–20 MHz) have greater sensitivity in identifying morphological changes allowing detection of minor injuries in small joints [20, 21]. Moreover, the inter-observer concordance analysis was performed in only six of the twelve studies included in the present review.

From the extracted data, many studies lack information on the relationship between the use of corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressants and US findings. These medications have a direct effect on inflammatory cells and serum cytokines and consequently may interfere with the US findings.

Despite the above-mentioned limitations of the studies included, one can draw important conclusions:

-

1)

The association between musculoskeletal US findings and disease activity in SLE as measured by SLEDAI score as well as serological markers is conflicting.

-

2)

Although the US findings were more common in SLE patients with joints symptoms or alterations on physical examination, the majority of articles showed that a substantial number of asymptomatic patients can have abnormalities at musculoskeletal US. Thus, relying only on physical examination of the joints in SLE patients may underestimate the presence of active joint inflammation.

In about 5 % of SLE patients, a deforming arthropathy (JA) progressively and slowly may occur. Curiously, there is not necessarily an association between disease activity, serology findings, and its development. Moreover, some lupus patients who develop JA have only mild previous joint manifestation. The same pattern may occur in patients with rheumatic fever [2]. Prospective studies are necessary to determine if the patients with subclinical joint abnormalities that were earlier identified by US have a higher risk for JA development.

References

Messuti L, Zoli A, Gremese E, Ferraccioli G (2014) Joint involvement in SLE: the controversy of RHUPUS. Int Trends Immun 2(4):155–161

Santiago MB, Galvao V (2008) Jaccoud arthropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis of clinical characteristics and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 87(1):37–44

Demirkaya E, Ozcakar L, Turker T et al (2009) Musculoskeletal sonography in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 61(1):58–60

Grossman JM (2009) Lupus arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 23(4):495–506

Ball EM, Bell AL (2012) Lupus arthritis–do we have a clinically useful classification? Rheumatology 51(5):771–779

Kaya A, Kara M, Tiftik T et al (2013) Ultrasonographic evaluation of the femoral cartilage thickness in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int 33(4):899–901

Kaya A, Kara M, Tiftik T (2013) Ultrasonographic evaluation of the muscle architecture in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Rheumatol 32(8):1155–1160

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 151(4):W65–W94

Dreyer L, Jacobsen S, Juul L, Terslev L (2014) Ultrasonographic abnormalities and inter-reader reliability in Danish patients with systemic lupus erythematosus - a comparison with clinical examination of wrist and metacarpophalangeal joints. Lupus. doi:10.1177/0961203314561666

Yoon HS, Kim KJ, Baek IW et al (2014) Ultrasonography is useful to detect subclinical synovitis in SLE patients without musculoskeletal involvement before symptoms appear. Clin Rheumatol 33(3):341–348

Iagnocco A, Ceccarelli F, Rizzo C et al (2014) Ultrasound evaluation of hand, wrist and foot joint synovitis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology 53(3):465–472

Gabba A, Piga M, Vacca A et al (2012) Joint and tendon involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus: an ultrasound study of hands and wrists in 108 patients. Rheumatology 51(12):2278–2285

Torrente-Segarra V, Lisbona MP, Rotes-Sala D et al (2013) Hand and wrist arthralgia in systemic lupus erythematosus is associated to ultrasonographic abnormalities. Joint Bone Spine 80(4):402–406

Iagnocco A, Ossandon A, Coari G et al (2004) Wrist joint involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. An ultrasonographic study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 22(5):621–624

Ossandon A, Iagnocco A, Alessandri C, Priori R, Conti F, Valesini G (2009) Ultrasonographic depiction of knee joint alterations in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27(2):329–332

Delle Sedie A, Riente L, Scire CA et al (2009) Ultrasound imaging for the rheumatologist. XXIV. Sonographic evaluation of wrist and hand joint and tendon involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol 27(6):897–901

Mosca M, Tani C, Carli L et al (2015) The role of imaging in the evaluation of joint involvement in 102 consecutive patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev 14(1):10–15

Wright S, Filippucci E, Grassi W, Grey A, Bell A (2006) Hand arthritis in systemic lupus erythematosus: an ultrasound pictorial essay. Lupus 15(8):501–506

Ball EM, Gibson DS, Bell AL, Rooney MR (2014) Plasma IL-6 levels correlate with clinical and ultrasound measures of arthritis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 23(1):46–56

Grassi W, Filippucci E, Farina A, Cervini C (2000) Sonographic imaging of tendons. Arthritis Rheum 43(5):969–976

Grassi W, Lamanna G, Farina A, Cervini C (1999) Synovitis of small joints: sonographic guided diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Ann Rheum Dis 58(10):595–597

Acknowledgments

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Mittermayer Barreto Santiago M.D., PhD. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article. The authors state that this work has not received any funding. No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper. Institutional review board approval was not required because the article is a systematic review.

M.S. received a scholarship from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lins, C.F., Santiago, M.B. Ultrasound evaluation of joints in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Eur Radiol 25, 2688–2692 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3670-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-015-3670-y