Abstract

To investigate biopsychosocial variables that contribute to explaining social support, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge in patients with fibromyalgia. A cross-sectional study. We built ten models of predictive variables (schooling, ethnicity, associated diseases, body regions affected by pain, employment status, monthly income, marital status, health level, medication, sports activities, interpersonal relationships, nutrition level, widespread pain, symptom severity, cohabitation, dependent people, number of children, social support, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge) and individually tested their explanatory performance to predict mean scores on the Fibromyalgia Knowledge Questionnaire (FKQ), Medical Outcomes Study’s Social Support Scale (MOS-SSS), and Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised (ASAS-R). We used analysis of variance to verify the association among all variables of mathematically adjusted models (F-value ≥ 2.20) and we reported only models corrected with p < 0.05 and R2 > 0.20. One hundred and ninety people with fibromyalgia (aged 42.3 ± 9.7 years) participated in the study. Our results show that the variables schooling, ethnicity, body regions affected by pain, frequency of sports activities, dependent people, number of children, widespread pain, social support, and self-care determine 27% of the mean FKQ scores. Marital status, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge determine 22% of mean MOS-SSS scores. Schooling, ethnicity, employment status, frequency of sports activities, nutrition level, cohabitation, number of children, social support, and fibromyalgia knowledge determine 30% of the mean ASAS-R scores. Studies using mean scores of social support, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge should collect and analyze the social variables described in the present study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The social variables (biopsychosocial model) help capture people’s experience of chronic pain by affirming that biological, neuropsychological, and socioenvironmental elements play a role in chronic pain-related processes [1]. These variables are embedded in the definition of health of the World Health Organization of 1948 where Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being—and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity [2]. The model was then detailed by the World Health Organization with the International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health, which addresses the complex interaction among health conditions, individuals, and the environment in which individuals conduct their lives, to understand health outcomes in terms of disability [2]. The social variables try to overcome the biomedical approach, centered on purely biological mechanisms, however, this evaluation model is neglected in some diseases characterized by musculoskeletal pain [3], such as fibromyalgia [4,5,6].

Fibromyalgia is a chronic disorder that has been investigated for over 70 years [7]. However, the pathophysiology, the best treatment, as well as the understanding of the mechanisms surrounding fibromyalgia remain unclear [8, 9]. Biological aspects, such as widespread pain [10], fatigue [7, 11], and severity of symptoms [12] are investigated in most studies as they are part of the diagnostic criteria [13,14,15]. Psychological aspects such as catastrophizing [16,17,18,19], kinesiophobia [20,21,22,23,24], and suicidal ideation are also widely researched using questionnaires [25,26,27]. However, the social variables (such as social support, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge) of fibromyalgia patients remain uninvestigated, consequently making it difficult to understand the impact of those variables on this disease.

So far, there are less than 50 studies on fibromyalgia and social variables, indicating the need of studies with this focus [6]. Furthermore, no study has verified whether the current diagnostic criteria for diagnosing fibromyalgia include any biopsychosocial variable [13,14,15]. As such, and considering that scientific knowledge advances are based on discoveries, this study aimed to investigate possible biopsychosocial variables that contribute to explaining social support, self-care management, and fibromyalgia knowledge. Our hypothesis is that current criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia (i.e., widespread pain and symptom severity) significantly interact with these variables.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study reported in accordance with the guidelines of the Strengthening Reporting of OBservational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [28]. All procedures in this study previously complied with Resolutions 466/2012 and 510/2016 of the National Health Council, contemplating international guidelines (Declaration of Helsinki), as well as regulatory norms for research involving human beings in Brazil. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de São Carlos (Report Number: 4.292.322, August 3rd, 2020) and developed online during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Setting

After approval, the study was disclosed through university dissemination channels and social media, such as Facebook®, WhatsApp®, and Instagram®, for a period of two months (from October 20, 2021, to December 20, 2021). Thus, interested people contacted the researchers, who sent a link to the electronic form to be completed. All data were collected using Google Forms®, whose information storage is automatically transferred to a Google Sheets® spreadsheet. The participants received written explanations about the procedures and steps of the study. When they agreed to participate in the research, they clicked on “I agree to participate in the research”. Informed consent form was presented in the first section of the online form and was available for printing or filing in.pdf format.

Participants

We calculated the sample, a priori, using SurveyMonkey®, using the parameters proposed by the epidemiological study by Souza and Perissinotti [29] regarding the prevalence of fibromyalgia in Brazil: four million people, statistical power of 80% and alpha of 5%. Thus, our sample was estimated at 164 participants. We included Brazilian adults (i.e., > 18 years old) of both sexes with a diagnosis of fibromyalgia according to the diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR-2016) [15]: Widespread Pain Index (WPI) ≥ 7 and the Symptom Severity Scale (SSS) ≥ 5 (or WPI > 4 + SSS > 9); pain in at least four of the five regions (axial, upper and lower limbs); persistent symptoms for at least three months.

Recruited participants received a booklet on chronic pain, containing information about the neuroscience of pain, coping with chronic pain, the importance of quality sleep, physical exercise, and relaxation tips (supplementary file 1). This booklet was sent in order to provide evidence-based information on chronic pain management to all study participants.

Data measurement

We divided the collection (via Google Forms®) into five sections: initial evaluation form; sociodemographic questionnaire; Medical Outcomes Study’s Social Support Scale (MOS-SSS), Appraisal of Self-Care Agency Scale-Revised (ASAS-R); and Fibromyalgia Knowledge Questionnaire (FKQ). The initial evaluation form (including the eligibility criteria [15]) and the sociodemographic questionnaire were prepared by the researchers (According to the country’s national survey). The use of medications and clinical conditions self-reported by patients are available in supplementary file 2.

MOS-SSS [30] was developed for the Medical Outcome Study [31] and adapted for the Brazilian population by Griep et al. [32, 33]. It contains 19 items with a five-point Likert scale (never = 1, rarely = 2, sometimes = 3, almost always = 4, always = 5) to assess the social support construct through four domains: material (items 1 to 4), affective (items 5 to 7), emotional/informational (items 8 to 14) and positive social association (items 15 to 19). The scores of each of the domains are obtained by ∑ of the points – minimum score. To standardize the results of all domains, we performed the following calculation: ([observed score – minimum score] / maximum score–minimum score × 100). The product of this ratio ranges from 0 to 100 per domain. The total score ranges from 0 to 400 (∑ of the 4 domains). A higher score means greater social support [32].

ASAS-R was adapted for the Brazilian population by Stacciarini [34]. It contains 15 items with a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree = 1, strongly agree = 5) to assess the self-care construct through three domains: having power (items 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 10) developing power (items 7, 8, 9, 12, and 13) and lacking power (items 4, 11, 14, and 15). The total score ranges from 15 to 75. Higher scores mean greater self-care ability [34].

FKQ was developed and validated by Suda et al. [35]. It contains 18 items to assess the specific knowledge of patients with fibromyalgia regarding fibromyalgia. The instrument is configured in four4 sections: items 1 to 5 about general fibromyalgia knowledge, 6 to 9 drugs in fibromyalgia, 10 to 13 exercises in fibromyalgia, and 14 to 18 joint protection and energy conservation [36]. The number of alternative correct answers is stated in the question itself so as not to confuse respondents, given that some questions contain more than one correct answer. The last alternative of all questions is always “I don’t know”, in order to avoid the possibility of patients answering without knowing the answer [35]. Each item receives 1 point when the patient answers the whole question correctly; otherwise, it receives a score proportional to the correct answers. The total score ranges from 0 to 18. Higher scores mean greater fibromyalgia knowledge.

Variables

Assessments generated 21 variables, whose description is configured as follows: education (five categories); ethnicity (four categories); associated diseases (two categories); body regions affected by pain (two categories); employment status (four categories); monthly income (five categories); marital status (seven categories); health level (five categories); medication (three categories); sports activities (six categories describing how often fibromyalgia prevented participation in team sports such as soccer, volleyball, basketball, and others); interpersonal relationships (six categories describing the frequency with which fibromyalgia prevented participation in face-to-face meetings of residents’ or employees’ associations, unions or parties, academic centers or similar); nutrition level (five categories); WPI + SSS (two categories); cohabitation (three categories); dependent people (three categories describing the number of people who depend on the care of the patient evaluated in this study); number of children (three categories); widespread pain (WPI); severity of symptoms (SSS); social support (MOS-SSS); self-care (ASAS-R); fibromyalgia knowledge (FKQ).

Statistical analysis

We checked the data normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and presented it as mean (standard-deviation) and absolute number (%). Besides, we verified the linearity of all variables, homogeneity of variance, independence of errors among independent variables, non-multicollinearity, and low exogeneity. Afterward, we performed a multiple linear regression using the univariate general linear model (sequence and criteria are described below). We established an alpha of 0.05 for all tests and performed the analyses using IBM® SPSS® Statistics for Windows, version 20.0. (Armonk, NY, USA).

We built 10 models and individually tested the explanatory performance of all of them for the FKQ, MOS-SSS, and ASAS-R instruments. In each of the models, we evaluated the association between predictor variables (i.e., independent, x-axis) and outcome variables (i.e., dependent, y-axis) through analysis of variances of mathematically adjusted models (F-value ≥ 2.20, p < 0.05) [37,38,39].

In the analysis of variances, we considered the null and alternative hypotheses of the respective test (H0: constructed model = model without predictor; H1: constructed model ≠ model without predictor). Thus, we accept and report only the corrected models with a significance level < 0.05 and coefficient of determination adjusted for the independent variables (R2) > 0.20, whose explanation indicates that the performance of the built model is capable of explaining the dependent variable. The R2 increases proportionally as we add new variables to the regression, so it is possible to have models with irrelevant variables and a high R2 (to avoid this we use the adjusted R2) [37,38,39].

Identifying the corrected models with a significance level < 0.05, we performed multiple linear regression on each of them. Through the univariate model, we built a term of the main effects of the independent variables on the dependent variables. Therefore, the association among them had a mathematically randomized predictive power. To obtain the beta coefficients of each of the associations between variables, we evaluated the parameter estimates considering null and alternative hypotheses (H0: beta coefficient = 0; H1: beta coefficient ≠ 0). Therefore, the significance of the beta coefficient (p < 0.05) represents the performance significance of the independent variable and covariates [37,38,39].

We used 16 independent variables as fixed factors, whose interpretation considers the following reference categories highlighted with an asterisk (*): education (graduate*), ethnicity (black*), associated diseases (yes*), body regions affected by pain (5*), employment status (active*), monthly income (> 6 wages*), marital status (widow*), health level (excellent*), medication (yes*), sports activities (≥ 2x /year*), interpersonal relationships (≥ 2x/year*), nutrition level (optimal*), WPI + SSS (> 21*), cohabitation (4 to 6*), dependents (4 to 5*) and number of children (3 to 4*). In addition, we used five covariates from the instruments: WPI, SSS, MOS-SSS, ASAS-R, and FKQ.

In model 1, we used the FKQ as the dependent variable (y-axis). Thus, we obtained the R2 using categorical independent variables (schooling, ethnicity, associated diseases, body regions affected by pain, employment status, monthly income, marital status, health level, medication, sports activities, interpersonal relationships, nutrition level, WPI + SSS score, cohabitation, dependent people, children) and numerical covariates (widespread pain, severity of symptoms, social support, self-care).

In models from 2 to 6, we used the MOS-SSS as the dependent variable (y-axis) with the following configuration: model 2 for domain 1, model 3 for domain 2, model 4 for domain 3, model 5 for domain 4, and model 6 for the total MOS-SSS score (i.e., the ∑ of the 4 domains, 0–400 points). Thus, we obtain the R2 using categorical independent variables (schooling, ethnicity, associated diseases, body regions affected by pain, employment situation, monthly income, marital status, health level, medication, sports activities, interpersonal relationships, nutrition level, WPI + SSS score, cohabitation, dependent people, and children) and numerical covariates (widespread pain, severity of symptoms, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge).

In models from 7 to 10, we used the ASAS-R as the dependent variable (y-axis) with the following configuration: model 7 for domain 1, model 8 for domain 2, model 9 for domain 3, and model 10 for the score ASAS-R total (i.e., the ∑ of the 3 domains, 15–75 points). Thus, we obtain the R2 using categorical independent variables (schooling, ethnicity, associated diseases, body regions affected by pain, employment situation, monthly income, marital status, health level, medication, sports activities, interpersonal relationships, nutrition level, WPI + SSS score, cohabitation, dependent people, and children) and numerical covariates (widespread pain, severity of symptoms, self-care and fibromyalgia knowledge).

Results

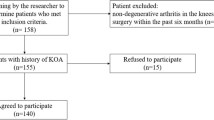

A total of 268 responses were collected, twelve of which were excluded for reporting continued use of alcohol and illicit drugs, and 66 did not meet the ACR-2016 [15] criteria. Finally, the sample of this study consisted of 190 patients with fibromyalgia aged between 20 and 76 years (mean age 42.3 ± 9.7 years), most of whom were female, with diseases associated with fibromyalgia, white ethnicity, monthly income of 1 to 2 salaries, married and taking medication (Tables 1 and 2).

Regarding fibromyalgia knowledge, we observed that the variables education, ethnicity, number of regions affected by pain, frequency of sports activities, dependent people, number of children, widespread pain, social support, and self-care significantly contribute (p < 0.05, β coefficient ranging from −5848 to 2779) for the performance of the built model (R2 = 0.27, p < 0.001). Namely, 27% of the variation in the mean FKQ scores can be explained by the independent variables. Significant categories, as well as other insignificant variables, are described in Table 3.

Regarding social support, we tested the performance of five corrected models and observed an R2 < 0.20 for the four MOS-SSS domains. Therefore, we report only the model built for the MOS-SSS with the sum of all domains (R2 > 0.20, p < 0.05), whose total score ranges from 0 to 400 points (Table 4). In this model, we observed that the variables marital status, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge contribute significantly (p < 0.05, β coefficient ranging between 5577 and 302,924) to the performance of the constructed model (R2 = 0.22, p = 0.001). Namely, 22% of the variation in the mean MOS-SSS scores can be explained by the independent variables.

Regarding self-care, we tested the performance of four corrected models and observed an R2 < 0.20 for domain 1 of the ASAS-R. Therefore, we report only models adjusted for domains 2, 3, and ASAS-R with the three domains (R2 > 0.20, p < 0.05), whose total score ranges from 15 to 75 points. In the model built for the ASAS-R with the three domains (Table 5), we observed that the variables education, ethnicity, employment situation, frequency of sports activities, nutrition level, cohabitation, number of children, social support, and fibromyalgia knowledge significantly contribute (p < 0.05, β coefficient ranging from −9003 to 2573) to the performance of the constructed model (R2 = 0.30, p < 0.001). Namely, 30% of the variation in mean ASAS-R scores can be explained by the independent variables.

Regarding domain 2 of the ASAS-R (Table 6), we observed that the variables frequency of sports activities and social support significantly contribute (p < 0.05, β coefficient ranging between 0.008 and 2.305) to the performance of the constructed model (R2 = 0.26, p < 0.001). In domain 3 of the ASAS-R (Table 7), we observed that the variables education, marital status, frequency of sports activities, nutrition level, and social support significantly contribute (p < 0.05, β coefficient ranging from −11.694 to 0.012) to the performance of the built model (R2 = 0.29, p < 0.001). Namely, from 26 to 29% the variations in the mean scores of the respective domains can be explained by the independent variables.

Discussion

We observed that 27% of the variation in mean scores of knowledge about the disease (fibromyalgia—FKQ) is explained by the independent variables tested (schooling, ethnicity, associated diseases, body regions affected by pain, employment status, monthly income, marital status, health level, medication, sports activities, interpersonal relationships, nutrition level, WPI + SSS, cohabitation, dependents, and number of children). We also observed that only widespread pain significantly interacted with social support (MOS-SSS), self-care (ASAS-R), and knowledge about the disease outcomes. Therefore, our hypothesis was rejected, pointing out that the current criteria for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia (ACR-2016) [15] partially contemplate some social variables, such as self-care agency, social support, and knowledge about the disease.

Our results showed that patients with fibromyalgia with primary education, compared to those with postgraduate degrees, have less knowledge about fibromyalgia. Considering the importance of health education for the treatment of the disease [40, 41]. We recommend that health professionals use language that is accessible to patients with low education levels. Regarding ethnicity, patients who report being yellow have lower levels of knowledge about the disease, as well as self-care, compared to those who report being black. Although ethnicity is a relevant variable in research on chronic pain [42], this is the first study that observed the association among ethnicity, fibromyalgia knowledge, and self-care.

We verified that patients who have four regions affected by pain have less knowledge about the disease compared to those who have five regions affected by pain. Wolfe et al. [43] describe that the number of body regions affected by pain, in patients with fibromyalgia, allows a better understanding of the results of research, serves as a guide for use in clinical care, and can be used for future reviews of diagnostic criteria for this disease. Regarding future diagnostic criteria, Toda [44] disagreed with this statement [43] and pointed out new criteria are already discussed [45].

Patients who perform sports activities 1x/year have less knowledge about the disease compared to those who attend 2x/year. Although physical activity, physical exercise, and sports activities have specific concepts, it is important to understand that they all include human physical exertion [46]. In this context, Mendoza-Muñoz et al. [47] found that women with fibromyalgia who understand the importance of physical activity for health have a better quality of life. However, the authors [47] found no association between knowledge of physical activity in fibromyalgia and the practice of physical exercise. Therefore, just like Mendoza-Muñoz et al. [47], we suggest further studies in this area.

Fibromyalgia patients who do not have people dependent on their care have greater knowledge about the disease compared to those who care for 4 to 5 people. Patients who do not have children have less knowledge about the disease than those who have 3 to 4 children. This indicates that patients with more free time acquire more knowledge about fibromyalgia. However, this same plausibility invalidates the lower score for patients who do not have children (compared to those who do), since children also depend on human care and require dedication of time. Therefore, we suggest further studies to understand the nature of this contradiction.

Regarding covariates, the two-dimensional rectangular Cartesian coordinates infer positive (WPI, MOS-SSS, p < 0.05) and negative (ASAS-R, p < 0.05) associations in the mean FKQ scores. Regarding the clinical applicability of these results, we emphasize that patients with higher levels of self-care should receive priority interventions in health education and pain neuroscience, as the self-care construct affects knowledge about the disease.

The association between marital status and social support, in this study, shows that patients who have not faced a loving partner's grief (i.e., dating, living together, married, separated, or divorced), compared to widowed patients, reach higher levels of self-care. Clinically, this means that the loss of a loving partner is associated with the loss of social support, thus stimulating self-care. Avis et al. [48] point out that there is still no defined model for discussing the stages of grief, as such, considering that this is the first study to address the biopsychosocial aspects of grief in patients with fibromyalgia, we suggest additional research in this context.

The association between schooling and self-care demonstrates that patients with fibromyalgia with incomplete elementary or high school education, compared to those with postgraduate degrees, have lower levels of self-care. This reinforces the discussion proposed by Arcaya and Saiz [49], whose approach suggests that lower education interferes with self-care.

Regarding employment status, patients who have already worked, compared to those active at the time of the survey, have lower levels of self-care. This inference shows that the loss of workability affects self-care. Our results corroborate the study by Collado et al. [50], whose finding indicates that patients with fibromyalgia who visit primary healthcare centers are negatively affected in terms of family and employment. Ben-Yosef et al. [51] certify that flexibility related to working hours is essential to keep patients functional and productive.

Regarding marital status, our study shows that patients who have not faced the grief of a loving partner, in relation to widowed patients, reach lower levels of self-care, certifying that single, dating, living together, married, separated, or divorced patients have lower levels of self-care. It is important to highlight that the inference of this parameter does not explain the reason why there is an increase in self-care in widowed patients. Therefore, further studies should investigate the effect of the experience built up over the relationship, the time spent with painful crises, and the patient’s ability to deal with grief.

Regarding sports activities, patients who do not attend, compared to those who attend ≥ 2x/year, reach lower levels of self-care. Those who attend 1x/week, compared to those who attend ≥ 2x/year, achieve higher scores. Therefore, we reinforce that patients who are more involved in sports activities have better prognoses [47]. Regarding the level of nutrition, patients who report having poor or more or less levels, compared to those who report an excellent level of nutrition, reach lower levels of self-care. Our results converge with the study proposed by Tomaino et al. [52], whose conclusion suggests that nutrition and/or nutritional intervention play a significant role in the severity of fibromyalgia.

Regarding cohabitation, patients who share a home with 1 to 3 people, compared to those who share it with 4 to 6, reach higher levels of self-care, indicating that sharing a home with a large number of people significantly affects the self-care of patients. patients with fibromyalgia. We emphasize that this analysis does not show whether self-care is reduced because more people are caring for the patient or vice versa. In view of this, we suggest further studies.

Patients who do not have, compared to those who have 3 to 4 children, reach lower levels of self-care. It is justifiable to predict that the feeling of protection is associated with other requirements, including self-care (i.e., to take care of a certain number of children, it is also necessary to take care of oneself). Furthermore, based on the covariates of positive (MOS-SSS, p < 0.001) and negative (FKQ, p = 0.031) associations on mean ASAS-R scores, increased social support to patients, even those with less fibromyalgia knowledge, encourages self-care in this population.

Studying fibromyalgia patients is a difficult task, as this population, usually, has several symptoms and may have other concomitant conditions. Our study has limitations that must be addressed. First, patient recruitment took place in an online format, with the burden of recruiting only people who had internet access, which does not reflect Brazilian reality [53] and may have led to a recruitment bias. Second, we did not evaluate all participants in person, and some issues regarding their understanding or their condition may have been overlooked; for example, in the question about people depending on the participant, we were not able to verify the reason for dependence (financial, physical, emotional). Third, given the multiplicity of outcomes and predictors, some of the findings are likely due to chance and do not represent generalizable patterns. Fourth, a detailed evaluation of regular exercise could have been performed rather than asking about sports activities. Fifth, in the sample, there are patients with rheumatological diseases, and disease activity was not evaluated, this may affect the parameters studied in the study. Sixth, in this study, almost 20% of the patients have psychiatric illnesses and are undergoing treatment, thus, the evaluation of these patients can be an important limitation of this study.

Conclusion

We conclude that the variables education, ethnicity, body regions affected by pain, frequency of sports activities, dependent people, number of children, widespread pain, social support, and self-care determine 27% of the mean FKQ scores. The variables marital status, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge determine 22% of the mean MOS-SSS scores. The variables education, ethnicity, employment situation, frequency of sports activities, nutrition level, cohabitation, number of children, social support, and fibromyalgia knowledge determine 30% of the mean ASAS-R scores.

Data availability

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third-party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

Childerhose JE, Cronin RM, Klatt MD, Schamess A (2023) Treating chronic pain in sickle cell disease - the need for a biopsychosocial model. N Engl J Med 388:1349–1351. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2301143

Rosignoli C, Ornello R, Onofri A et al (2022) Applying a biopsychosocial model to migraine: rationale and clinical implications. J Headache Pain 23:100. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-022-01471-3

Miaskowski C, Blyth F, Nicosia F et al (2020) A biopsychosocial model of chronic pain for older adults. Pain Med 21:1793–1805. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnz329

Da Silva Almeida DO, Pontes-Silva A, Dibai-Filho AV et al (2023) Women with fibromyalgia (ACR criteria) compared with women diagnosed by doctors and women with osteoarthritis: cross-sectional study using functional and clinical variables. Int J Rheum Dis. https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185X.14720

Pontes-Silva A, de Sousa AP, Dibai-Filho AV et al (2023) Do the instruments used to assess fibromyalgia symptoms according to American College of Rheumatology criteria generate similar scores in other chronic musculoskeletal pain? BMC Musculoskelet Disord 24:467. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-023-06572-x

Pontes-Silva A (2023) Fibromyalgia: are we using the biopsychosocial model? Autoimmun Rev 22(1):103235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2022.103235

Bazzichi L, Giacomelli C, Consensi A et al (2020) One year in review 2020: fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 38 Suppl 123(1):3–8

D’Agnelli S, Arendt-Nielsen L, Gerra MC et al (2019) Fibromyalgia: genetics and epigenetics insights may provide the basis for the development of diagnostic biomarkers. Mol Pain 15:1744806918819944. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744806918819944

Erdrich S, Hawrelak JA, Myers SP, Harnett JE (2020) Determining the association between fibromyalgia, the gut microbiome and its biomarkers: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21:181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03201-9

Wolfe F, Egloff N, Häuser W (2016) Widespread pain and low widespread pain index scores among fibromyalgia-positive cases assessed with the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia criteria. J Rheumatol 43:1743–1748. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.160153

Estévez-López F, Maestre-Cascales C, Russell D et al (2021) Effectiveness of exercise on fatigue and sleep quality in fibromyalgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 102:752–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.019

Shaikh N, Kurs-Lasky M, Hoberman A (2019) Modification of the acute otitis media symptom severity scale. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 122:170–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.04.026

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A et al (2010) The American college of rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 62:600–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20140

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A et al (2011) Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 38:1113–1122. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.100594

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A et al (2016) 2016 Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum 46:319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012

Izquierdo-Alventosa R, Inglés M, Cortés-Amador S et al (2020) Low-intensity physical exercise improves pain catastrophizing and other psychological and physical aspects in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103634

Edwards RR, Bingham CO 3rd, Bathon J, Haythornthwaite JA (2006) Catastrophizing and pain in arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Rheum 55:325–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.21865

Peñacoba C, Pastor-Mira MÁ, Suso-Ribera C et al (2021) Activity patterns and functioning. A contextual-functional approach to pain catastrophizing in women with fibromyalgia. int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18105394

Varallo G, Scarpina F, Giusti EM et al (2021) The role of pain catastrophizing and pain acceptance in performance-based and self-reported physical functioning in individuals with fibromyalgia and obesity. J Pers Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11080810

Serrat M, Almirall M, Musté M et al (2020) Effectiveness of a multicomponent treatment for fibromyalgia based on pain neuroscience education, exercise therapy, psychological support, and nature exposure (NAT-FM): a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9103348

İnal Ö, Aras B, Salar S (2020) Investigation of the relationship between kinesiophobia and sensory processing in fibromyalgia patients. Somatosens Mot Res 37:92–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/08990220.2020.1742104

KoÇyİĞİt BF, Akaltun MS (2020) Kinesiophobia levels in fibromyalgia syndrome and the relationship between pain, disease activity, depression. Arch Rheumatol 35:214–219. https://doi.org/10.46497/ArchRheumatol.2020.7432

Varallo G, Suso-Ribera C, Ghiggia A et al (2022) Catastrophizing, kinesiophobia, and acceptance as mediators of the relationship between perceived pain severity, self-reported and performance-based physical function in women with fibromyalgia and obesity. J Pain Res 15:3017–3029. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S370718

Leon-Llamas JL, Murillo-Garcia A, Villafaina S et al (2022) Relationship between Kinesiophobia and mobility, impact of the disease, and fear of falling in women with and without fibromyalgia: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148257

Galvez-Sánchez CM, Duschek S, Reyes Del Paso GA (2019) Psychological impact of fibromyalgia: current perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag 12:117–127. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S178240

Ordóñez-Carrasco JL, Sánchez-Castelló M, Calandre EP et al (2020) suicidal ideation profiles in patients with fibromyalgia using transdiagnostic psychological and fibromyalgia-associated variables. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010209

Calandre EP, Ordoñez-Carrasco JL, Rico-Villademoros F (2021) Marital adjustment in patients with fibromyalgia: its association with suicidal ideation and related factors A cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 39(Suppl 1):89–94. https://doi.org/10.55563/clinexprheumatol/pufzd6

Malta M, Cardoso LO, Bastos FI et al (2010) STROBE initiative: guidelines on reporting observational studies. Rev Saude Publica 44:559–565. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102010000300021

de Souza JB, Perissinotti DMN (2018) The prevalence of fibromyalgia in Brazil – a population-based study with secondary data of the study on chronic pain prevalence in Brazil. Brazilian J Pain 1:345–348. https://doi.org/10.5935/2595-0118.20180065

Griep R, Chor D, Faerstein E, Werneck GLC (2005) Validade de constructo da escala de apoio social do Medical outcomes study adaptada para o português no Estudo Pró-Saúde. Cad Saúde Pública 21(3). https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2005000300004

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL (1991) The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32:705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-B

Griep RH, Chor D, Faerstein E, Lopes C (2003) Apoio social: confiabilidade teste-reteste de escala no Estudo Pró-Saúde. Cad Saude Publica 19:625–634. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2003000200029

Griep RH, Chor D, Faerstein E et al (2005) Validade de constructo de escala de apoio social do medical outcomes study adaptada para o português no Estudo Pró-Saúde. Cad Saude Publica 21:703–714. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-311X2005000300004

Stacciarini TSG (2012) Adaptação e validação da escala para avaliar a capacidade de autocuidado. Univ São Paulo

Suda AL, Jennings F, Bueno VC, Natour J (2012) Development and validation of fibromyalgia knowledge questionnaire: FKQ. Rheumatol Int 32:655–662. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-010-1627-7

Moretti FA, Heymann RE, Marvulle V et al (2011) Avaliação do nível de conhecimento sobre fibromialgia entre usuários da internet. Rev Bras Reumatol 51:13–19. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0482-50042011000100002

Nakagawa S, Johnson PCD, Schielzeth H (2017) The coefficient of determination R2 and intra-class correlation coefficient from generalized linear mixed-effects models revisited and expanded. J R Soc Interface. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2017.0213

Saunders LJ, Russell RA, Crabb DP (2012) The coefficient of determination: what determines a useful R2 statistic? Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 53(11):6830–6832. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-10598

Edwards LJ, Muller KE, Wolfinger RD et al (2008) An R2 statistic for fixed effects in the linear mixed model. Stat Med 27:6137–6157. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3429

Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE et al (2017) EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 76:318–328. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724

Häuser W, Ablin J, Fitzcharles M-A et al (2015) Fibromyalgia. Nat Rev Dis Prim 1:15022. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2015.22

Orhan C, Van Looveren E, Cagnie B et al (2018) Are pain beliefs, cognitions, and behaviors influenced by race, ethnicity, and culture in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Pain Physician 21:541–558

Wolfe F, Butler SH, Fitzcharles M et al (2019) Revised chronic widespread pain criteria: development from and integration with fibromyalgia criteria. Scand J pain 20:77–86. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2019-0054

Toda K (2020) Should we use linked chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria? Scand J Pain 20(2):421. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2019-0165

Arnold LM, Bennett RM, Crofford LJ et al (2019) AAPT diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Pain 20:611–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2018.10.008

Pontes-Silva A (2022) A mathematical model to compare muscle-strengthening exercises in the musculoskeletal rehabilitation. Musculoskelet Sci Pract 6:102635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2022.102635

Mendoza-Muñoz M, Morenas-Martín J, Rodal M et al (2021) Knowledge about fibromyalgia in fibromyalgia patients and its relation to HRQoL and physical activity. Biology (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/biology10070673

Avis KA, Stroebe M, Schut H (2021) Stages of grief portrayed on the internet: a systematic analysis and critical appraisal. Front Psychol 12:772696. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.772696

Arcaya MC, Saiz A (2020) Does education really not matter for health? Soc Sci Med 258:113094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113094

Collado A, Gomez E, Coscolla R et al (2014) Work, family and social environment in patients with fibromyalgia in Spain: an epidemiological study: EPIFFAC study. BMC Health Serv Res 14:513. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0513-5

Ben-Yosef M, Tanai G, Buskila D et al (2020) Fibromyalgia and its consequent disability. Isr Med Assoc J 22(7):446-450

Tomaino L, Serra-Majem L, Martini S et al (2021) Fibromyalgia and nutrition: an updated review. J Am Coll Nutr 40:665–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2020.1813059

IBGE — Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (2021) Use of internet, television, and cell phones in Brazil

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants of the present study. The authors would like to thank Mr. Guilherme Tavares de Arruda (PT, MSc, PhD student) for the help on the assessment of the study’s first draft. We also would like to thank funders: Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Brazil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001, The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Grant Number 2020/08870-8 (IN). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was partially supported by Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel—Brazil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001, The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant number 2020/08870–8 (IN). Role of funding sources: The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AP-S: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data analysis and interpretation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; IN: Data collection; Data analysis, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; AM-R: Data analysis and interpretation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; MCS: Conceptualization, Data interpretation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; JMD: Conceptualization, Data interpretation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing; MAA: Conceptualization, Project Administration, Funding requisition, data interpretation, Conceptualization, Data interpretation, Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pontes-Silva, A., Nunes, I., De Miguel-Rubio, A. et al. Social variables for replication of studies using mean scores of social support, self-care, and fibromyalgia knowledge: a cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Int 43, 1705–1721 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05374-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-023-05374-7