Abstract

Physical exercise has been used as a form of treatment for fibromyalgia, however, the results indicate the need for further investigations on the effect of exercise on different symptoms. The aim of the study was to synthesize and analyse studies related to the effect of exercise in individuals with fibromyalgia and provide practical recommendations for practitioners and exercise professionals. A search was carried out in the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases in search of randomized clinical trials (RCT) written in English. A meta-analysis was performed to determine the effectiveness of different types of exercise on the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ), and the protocol period and session duration on the pain outcome. Eighteen articles were eligible for a qualitative assessment and 16 were included in the meta-analysis. The exercise showed large evidence for the association with a reduction in the FIQ (SMD − 0.98; 95% CI − 1.49 to − 0.48). Protocols between 13 and 24 weeks (SMD − 1.02; 95% CI − 1.53 to − 0.50), with a session time of less than 30 min (SMD − 0.68 95% CI − 1.26 to − 0.11) or > 30 min and < 60 min (SMD − 1.06; 95% CI − 1.58 to − 0.53) presented better results. Better results were found after combined training protocols and aerobic exercises. It is suggested that exercise programs lasting 13–24 weeks should be used to reduce pain, and each session should last between 30 and 60 min. In addition, the intensity should always be carried out gradually and progressively.

PROSPERO registration number CRD42020198151.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fibromyalgia is defined as a chronic rheumatological disease that causes sensory changes and musculoskeletal pain [1]. Different aspects are presented regarding the origin of the pathology, with some authors defending the hyperexcitability of the central nervous system, while others point to the imbalance of neurotransmitters [2,3,4].

Although a vast number of symptoms are related to fibromyalgia, widespread pain, fatigue, and muscle weakness are the primary symptoms [5,6,7]. As the exact cause of the origin of fibromyalgia is not known, although there is a clinical diagnosis for this condition, there is a possibility of bias during the performance of tests or of underestimated diagnoses [8]. Treatment for this syndrome aims to reduce the signs and symptoms presented by the individual in different domains (e.g., neurological, rheumatological) [7,8,9].

Physical exercise has frequently been used as a form of non-pharmacological treatment [10,11,12]. Besides it being a low-cost intervention, exercise has come to be described as one of the best allies in reducing symptoms, in addition to promoting health [12,13,14,15]. Reducing the number of tender points, and the impact of the disease on daily activities and pain, as well as improving sleep and functional capacity, are just some of the benefits of exercise in individuals with fibromyalgia [16,17,18]. In addition to the aforementioned physical factors, physical exercise is effective in improving pain perception and modulation, in addition to improving vitality, depression, and quality of life [19,20,21,22,23].

In the literature, it is possible to find several studies that aim to evaluate the effects of aerobic exercises [24,25,26,27], strength exercises [10, 15, 28,29,30], flexibility [31, 32], and combined exercises [33, 34]. Some recently published systematic reviews demonstrate that exercise practice is efficient in reducing common physical and psychological symptoms among individuals with fibromyalgia, however, the results indicate the need for further investigations on the effect of exercise on different symptoms [15, 35]. Furthermore, investigations into the prescription of physical exercise and its implications are essential both for patients who need treatment and for health professionals who can use evidence-based clinical practice to make the best decisions during treatment.

Therefore, given the known benefits of physical exercise in the population with fibromyalgia and the lack of indicators regarding the type, duration, and intensity of exercise, the present study aims to synthesize and analyse the effects of different physical exercise protocols in individuals with fibromyalgia, through seeking to investigate the effectiveness of the interventions performed and their effects on the main symptoms.

Methods

Search strategy

The literature search was carried out in the Web of Science, Medline, and Scopus platforms, using the PICO (population, intervention, control, and outcome) research strategy. Literature published up to 14 April 2022 was included. Two reviewers (MLLA and HPN) independently performed the search and assessed the eligibility of each article. Doubts regarding the inclusion or exclusion of studies were resolved by discussion between the two independent researchers. To guarantee the quality of the study the protocols established by PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) were used [36]. The search terms used in the database search were: “fibromyalgia”, “Physical Activity”, “Exercise”, “Strength”, “flexibility”, “Aerobic Exercise”, “Resistance Exercise”, “Randomized Controlled Trial”, using the search expression Fibromyalgia) AND (Exercise) OR (strength) OR (flexibility) OR (aerobic) OR (resistance) OR (randomized controlled trial). Although there was no restriction in the search period, there was a specification as to the type of document and language, with scientific articles written in English being selected. This review was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO (registration no. CRD42020198151).

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review were: (i) randomized clinical trials (RCT); (ii) a study population over the age of eighteen; (iii) a diagnosis of fibromyalgia following the criteria established by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [1, 37]; (iv) an intervention protocol for a minimum period of four weeks; (v) aimed to evaluate the effects of a presential protocol consisting of physical exercise; (vi) use assessment instruments that analyse at least one of the symptoms presented by typical fibromyalgia patients (e.g., pain, depression, sleep, anxiety …); and (vii) present at least one intervention group and a control group without any type of intervention. The following documents were excluded from this systematic review: (i) literature reviews of any kind; ii) theses and dissertations (master's and doctorate); (iii) articles composed of multidisciplinary/interdisciplinary interventions; (iv) educational or cognitive-behavioural therapies; (v) articles that presented subjects with more than one medical diagnosis in addition to fibromyalgia; vi) investigations without a control group and physical exercise programs specific to a single modality or therapy.

Selection of studies

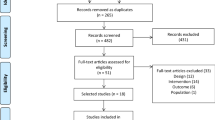

The selection of articles was carried out following the PRISMA recommendations [36]. Reference software (Endnote, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) was used to unify articles from different databases and then exclude duplicates. After the exclusion of duplicates, the title was read and then the abstracts were read, with non-relevant articles excluded. The articles eligible for the qualitative analysis were selected after complete reading of the remaining articles according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria previously mentioned in this study. This process was carried out by two reviewers (MLLA and HN) to reduce the risk of bias.

Data extraction

After defining the articles for inclusion in this study, data were extracted related to the parameters evaluated by each article and their respective analysis instruments, intervention period, number of sessions, details of the interventions, and their effects compared to control groups. The respective variables analysed in the articles were also extracted (e.g., pain, anxiety, depression). All extracted variables are detailed in the results. The authors of the articles that did not provide the necessary data for the meta-analysis were contacted by e-mail to acquire the information. For those who did not respond, the necessary information was acquired through old systematic reviews.

Bias risk assessment

The analysis of the risk of bias was performed by two researchers, separately (MLLA and HPN) and was carried out according to the methods recommended by Cochrane [38], bias according to, the following criteria: (1) generation of random sequence; (2) concealment of allocation; (3) blinding of participants and professionals; (4) blinding of outcome evaluators; (5) incomplete outcomes; (6) report of selective outcome; (7) other sources of bias. For these criteria, the following classifications were used: high risk of bias, low risk of bias, and uncertain risk of bias (the latter case when there was a lack of information or when there was any kind of doubt about the information found in the articles). For the creation of graphics referring to the risk of bias, Review Manager Software (RevMan, The Nordic Cochrane Center, Copenhagen, Denmark), version 5.4 was used.

Data analysis

The results of the studies were recalculated to determine the magnitude of the differences in the studied variables between the control and experimental groups. The percentage difference between the experimental group and the control group ([experimental group − control group/control group) × 100]) was calculated considering the average values presented by the studies that provided this information. To identify the gains or losses from the exercise, symbols were used to compare the control group with the experimental group, specifically “ > ” (higher than) and “ < ” (lower than). The meta-analysis was performed with RevMan 5.4 to determine the effects of the different types of exercises (i.e., aerobic, strength, and combined) and exercise durations (intervention period and time per session) on pain and on the FIQ domains. These variables were the most commonly used outcomes in the included studies, and thus considered the most relevant for further analysis. To assess the differences between the exercise interventions and the control group, the means and respective standard deviations were used as effect measures. Only articles that provided this information were included in the meta-analysis. The I2 was used to measure the heterogeneity of the RCTs, considering the classification established by Higgins et al. [39] (I2 < 25% low; I2 = 50–75% moderate; I2 > 75% high).To classify the magnitude of the effect size of the SMD the category of Cohen was selected (d values between 0.2 and 0.5 represent a small effect size; between 0.5 and 0.8 a medium effect size; greater than 0.8 a large effect size) [40]. Negative values of effect size in this meta-analysis favour the exercise intervention, while positive values favour the control group. All articles classified as combined interventions performed two different exercise modalities (e.g., aerobic and strength) in their intervention protocols. Aerobic interventions were considered those exercise programs aiming to increase cardiovascular response to exercise (e.g., increased heart rate, oxygen uptake) by performing specific activities such as walking, running, aquatic exercise, cycling, while the strength interventions included exercises aiming to improve muscular fitness by exercising a muscle or a muscle group against an external resistance or using bodyweight resistance.

Results

After the exclusion of duplicates, a total of 420 articles were eligible for this review. Following the analysis of the titles, 193 articles were read in full to check the criteria, resulting in 18 articles to be included in the quality review and 16 articles for the meta-analysis. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the included studies, specifically participants, duration, intervention, and main outcomes. Among the different evaluated variables, pain was the most analysed parameter (77.8% of the articles). The second and third most investigated variables were the FIQ and strength with 61.1% and 55.6% of the manuscripts, respectively. The minimum intervention period presented by one of the articles was 8 weeks [26, 41], while the maximum period lasted 8 months [42]. Regarding the frequency and duration of each session, 55.6% of the articles had a frequency of two sessions per week and 44.4% included three sessions per week. The shortest session duration, in one study, was 30 min[43] and the maximum session time ranged from 60 to 90 min [44].

Regarding the exercise protocols used, only one study evaluated a stretching protocol (4.7%) [19], six addressed strength exercises (28.6%) [10, 19, 45, 46, 51, 54], and six focused on aerobic exercise (28.6%) [26, 34, 43, 46, 48, 52]. The strength programs were carried out on the ground in four studies and one study combined aquatic and ground exercise. The aerobic exercise was implemented on the ground (n = 5) and combining aquatic and ground exercise (n = 1). Most studies (38.1%) carried out a combined protocol. Of the eight articles with combined therapies, 50% were performed in water and 50% used the ground. From the total of 18 articles, approximately 39% used water as a means of intervention and 61% used the ground to perform the exercises.

Regarding the intensity, while some studies started with 40–50% RM and progressed up to 80% RM, for strength gain most articles used 60–65% RM as a starting point. Eight (44.5%) articles created a protocol for the progression of exercise intensity each week, while others performed the adjustment at each session depending on the participant's tolerance.

Some outcomes were assessed by more than one article and specific exercise protocols had a greater impact on symptom improvement in the populations evaluated, namely: reduced pain (36.9%) [46], reduced FIQ (34.9%) [46], improved quality of life (60.5%) [19], increased pressure pain threshold (86.4%) [51], reduced depression (52%) [10] and anxiety (24%) [52], and increased balance (57.2%) [51].

Regarding the risks of bias, although all the articles included were RCTs, 55.6% of the studies demonstrated a low risk of bias for generation of random sequence and 61.1% an uncertain risk of bias for allocation concealment (Fig. 2). Only 38.9% of the articles had a low risk of bias for blinding of participants and professionals.

The meta-analysis presented in Fig. 3 provides a comparison of exercise and a control group for the FIQ because of different types of exercise intervention. All exercise interventions were shown to have a beneficial effect on reducing the FIQ (SMD − 0.98; 95% CI − 1.49 to − 0.48). As for the analysis of the subgroups, the aerobic training demonstrated a high effect size while the strength intervention had a moderate effect. Despite the high heterogeneity presented by the combined intervention groups, the effect size (SMD − 1.34; 95% CI − 2.2 to − 0.06) also favoured the practice of exercise to reduce the FIQ.

Considering the pain outcome as one of the most relevant variables for the individual with fibromyalgia, a deeper analysis of the intervention period (Fig. 4) and session time (Fig. 5) was performed. No significant results were found for protocols with a duration lower than 12 weeks or greater than 24 weeks. Protocols between 13 and 24 weeks, on the other hand, had a high effect size, but with a high heterogeneity index.

Regarding the session duration, only one study performed sessions with a duration equal to or lower than 30 min, with moderate effects on pain relief. There was a reduction in pain in the intervention subgroups with interventions between 30 and 60 min, despite high heterogeneity observed between the studies. When the intervention lasted for more than 60 min, the result was not significant (Fig. 5).

Discussion

The main objective of this systematic review with meta-analysis was to investigate the influence of physical exercise programs in individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia and to summarize the respective effects. Results showed that strength training, aerobic training, and combined exercise programs resulted in favourable effects on fibromyalgia symptoms. Among these, the aerobic and combined interventions presented the highest effects on reducing the FIQ. Flexibility interventions, however, were not significant for reducing it. Greater improvements in pain relief seemed to occur in exercise programs that lasted between 13 and 24 weeks and using training sessions that lasted no more than 60 min. Although the physical and psychosocial status impact the response to the treatment of fibromyalgia, and the progression of exercise depends on the symptoms presented by the individual [55], the training protocols that followed a gradual progression of intensity, specifically monitoring heart rate or % of maximal load, seemed to more consistently reduce symptomatology [10, 19, 41, 46, 50].

Analyzing the results included in this review, almost all articles had a beneficial effect on at least one of the evaluated parameters. The training programs that had the most positive effects on a greater number of symptoms were in the studies of Roman et al. [51], Gowans et al. [43] and Munguia-Izquierdo and Legaz-Arrese [50], during strength training, aerobic, and combined interventions, respectively. In line with these results, Geneen et al. [56] showed that aerobic activities and strength exercises proved to be beneficial for this population and Bidonde et al. [57] suggested an effect of combined interventions.

The literature presents different training methods (i.e., aerobic, strength, flexibility and combined interventions), but a common factor among them is the use of aquatic exercises, either alone or alternating with land-based exercise. The properties of water and the physical activity performed in a heated swimming pool seemed to positively affect different systems of the human body [58, 59]. As a consequence, these physiological changes can assist in the relaxation of body muscles, improve blood flow, and allow muscle strengthening due to the resistance generated by the water [58, 59]. Given the benefits, the practice of physical exercise in water has been strongly indicated to reduce common symptoms in this specific population, such as pain, anxiety, and depression as well as being effective for increasing the physical capacity of these individuals [25, 60, 61].

The meta-analysis allowed us to further understand the effects of exercise in reducing the impact of fibromyalgia assessed by the FIQ. The three different types of exercises were able to improve the indicators associated with the FIQ and consequently reduce the fibromyalgia symptoms. The aerobic and strength protocols showed a moderate and high effect size; however, the combined protocols presented the greatest effect size. The high heterogeneity reveals a trend towards the need for further investigations on combined interventions with a better focus on methodological quality. Although blinding of intervention between evaluators and participants is desirable, blinding is difficult in intervention trials [62]. These results can be corroborated by Bidonde et al. [57] who presented low to moderate evidence of combined exercise in the different parameters related to fibromyalgia.

To facilitate the analysis of the intervention period and frequency, the articles were divided into categories: (i) < 12 weeks (3 months); (ii) 13–24 weeks (between 3 and 5 months); and (iii) > 24 weeks (> 6 months). All the aerobic exercise programs included in the meta-analysis had a duration of over 13 weeks. To promote positive effects, it is suggested that an aerobic protocol should have a frequency of two to three sessions per week and an intervention period composed of at least 4–6 weeks [63]. These results are supported by a recent study that also emphasized the importance of strength training in addition to aerobic training with 30–60 min per session [14]. In addition to this information, specifically for the pain outcome, protocols below 12 weeks and above 24 weeks did not demonstrate significant effects between the treatment group and control. Although these results favour the period of 13–24 weeks, it is essential to critically analyze these results, due to the heterogeneity between the protocols. This difference may exist due to differences in intensities and environment (aquatic or ground), among other factors, in addition to the methodological quality of each study. One can speculate that short durations are not enough to provide adaptations in pain, and very long interventions might lead to some reduced efficacy. However, we should be aware that only two studies focused on interventions that lasted 12 weeks or less [19, 42], and only one study focused on interventions longer than 24 weeks [43]. It would be expected that longer durations would result in greater improvements, but the low and steady intensity throughout the training program, the limited recovery of the patients' condition, and/or the few participants (decreasing the statistical power to detect some changes) may have influenced the results [43]. Nevertheless, from a qualitative perspective, all articles showed benefits in at least one of the assessed symptoms, reinforcing the results of Busch et al. [64] For the articles classified in the second classification (13–24 weeks), there was a predominance of interventions with a frequency of two training sessions per week, including aerobic, strength, or combined protocols.

The frequency and intensity of symptoms can incapacitate individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia. One way to interrupt the vicious circle of fibromyalgia is to replace 30 min of physical inactivity with light to moderate physical activity [20]. The results of this meta-analysis revealed that greater effects were observed after exercises performed for 30–60 min. To ensure the benefits of interventions lasting up to 30 min, further studies are needed.

In relation to strength training and despite the differences found in the articles regarding the intensity adopted at the beginning of the exercises performed, it is suggested that the intervention start with low intensity (40% of 1RM) and gradually increase the intensity [30]. With an aerobic focus, the most common intensity used was approximately 40–65% of maximum heart rate (MHR) in the initial phase of the exercise programs and then progression was made up to 80% MHR. Interventions should follow a well-structured protocol, that respects the individual's evolution. Each exercise should be performed with the appropriate intensity to reduce the risk of symptom increase. Otherwise, there will be a risk of worsening symptoms [65, 66].

Several studies reported the benefits of aerobic exercise for reducing the signs and symptoms presented by patients with fibromyalgia [27, 67, 68]. Six articles had the objective of evaluating the effects of an aerobic intervention protocol, but only four studies used instruments to assess cardiovascular parameters or performed analysis of aerobic capacity. The other studies chose to evaluate mainly the subjective effects of the applied training program, with positive results on pain, depression, quality of life, the FIQ, and the pressure pain threshold. Although aerobic exercise is widely indicated, different factors can create barriers and consequently affect the results expected. For instance, aerobic exercise programs with high intensities can be directly related to the individual's non-adherence to training [69]. All aerobic exercise protocols were performed with a maximum time of 60 min, with the Gowans et al.[43] study having the shortest aerobic intervention time, consisting of 30 min with significant results. As it is known that individuals with fibromyalgia have a low level of physical condition and consequently low tolerance to exercise, some authors suggested a reduction in the duration of the sessions and an increase in the frequency of exercises for the population with fibromyalgia [17, 70, 71]. Moreover, professionals should prioritize lower intensities to favour adherence to the activities and maintenance of the frequency throughout the program [17, 70, 71].

When focusing on the strength training programs, studies showed a moderate effect size on the FIQ. The literature suggests that these protocols can reduce the number of tender points, improve balance, and reduce depression [15, 30]. These results are corroborated by the Busch et al. [64] study. Forty-three percent of the studies that presented a session time between 30 and 60 min included a strength protocol as the intervention and the higher percentages of strength gain occurred in medium intervention programs [10]. Among the studies that assessed the effects of strength training, the study by Hakkinen et al. [10] obtained the highest percentage strength gain, despite the lower number of sessions during the intervention period when compared to the study of Roman et al. [51]. Roman et al. [51] achieved good strength gains and positive results in other subjective parameters, such as the FIQ and a reduction in the pain threshold. The good results in the study of Hakkinen et al. [10] could be caused by the clearly defined progression of loads every 3 weeks and consequent adjustments that were made repeatedly to guarantee progression and adaptations. On the contrary, the study of Roman et al. [51] consisted of a strength intervention, carried out on the ground and in water, with variations in intensity and no clear description of load progression, perhaps leading to lower positive results related to strength gain. These differences between the types of training, in addition to the alternation in training environments, may justify the different gains between studies since exercises performed in a heated aquatic environment bring more benefits when compared to the ground [25].

The combined protocols demonstrated a high effect, specifically in reducing the FIQ. Busch et al. [64] found some limitations regarding the combined exercise protocols performed, which culminated in a lack of data regarding this exercise type. In a recent study carried out by Bidonde et al. [57] the effects of the combined practice were clear, despite the low evidence and great heterogeneity found, a factor that corroborates the findings of the present study. The high rate of heterogeneity in these exercise programs could be justified by the existence of variation in session time (45–90 min), total intervention time (15–24 weeks), and different types of intervention. The environment in which the intervention was carried out (aquatic environment and others) could also be a factor that increases the heterogeneity between studies. In addition to these factors, the methodological quality of the studies must be taken into account. Thus, in a qualitative analysis of the findings, we should highlight that combined training showed promising results, such as reducing the FIQ [70], and depression [42], and improving aerobic capacity [72] and muscle strength [48]. To achieve these benefits in this population, it is suggested that the exercises should start lightly and there should be a gradual increase in intensity over time, always within what is bearable by the individual, to obtain the desired positive effects [17].

The intervention consisting of flexibility exercises did not provide evidence of a significant reduction in the symptoms of fibromyalgia assessed by the FIQ. Although some authors suggested the prescription of stretches to improve the symptoms associated with fibromyalgia, there is still a scarcity of studies on the effects of this type of exercise in this population [32, 73].

Limitations and future perspectives

Despite the important contributions of this systematic review to fibromyalgia, especially regarding interventions performed using physical exercise and their effects on subjects diagnosed with fibromyalgia, some limitations should be mentioned. Limitations in the studies themselves might have influenced the results, such as the lack of information regarding the training program, namely load progressions (intensity and volume) during the intervention period, or incomplete information that made it impossible to analyse some variables. For example, not all articles evaluated in this review described complete data about the duration of the sessions and/or the intensity of the exercises performed, or the gains between the groups analysed, and this hindered the possibility of determining changes in all variables. Due to the difference in methodological quality presented by the studies included in this systematic review, the risk of bias presented in some protocols, and the heterogeneity of the exercise protocols (e.g., different durations, intensities, and activities performed), the results found should be carefully considered and analysed. Future investigations should be carefully designed to have greater methodological rigour and thus reduce the risk of bias. In addition, further research should focus on different exercise programs, such as understanding the effects of stretching on the symptoms of fibromyalgia.

Conclusion

The results confirmed that the practice of physical exercise seems to be beneficial for the improvement in symptoms and physical fitness of individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia. Thus, intervention protocols that have a more global positive effect on the main symptoms found in these individuals are suitable and can be used as a possible adjunctive treatment tool. Physical exercise in general (aerobic, strength, or combined) has been shown to be beneficial for individuals with fibromyalgia, but greater results were found after combined training protocols and aerobic exercises. Strength interventions presented a moderate effect on FIQ. Literature findings suggested that exercise programs lasting 13–24 weeks should be used to reduce pain, and each session should last between 30 and 60 min. Furthermore, it is recommended that each training program should start at light intensity with gradually increasing intensity over time. Otherwise, it may have a reverse effect, which could aggravate the symptoms of the affected individuals.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- FIQ:

-

Fibromyalgia impact questionnaire

- MHR:

-

Maximum heart rate

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCT:

-

Randomized clinical trials

- RM:

-

Repetition maximum

- SMD:

-

Standardized mean difference

References

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, Goldenberg DL, Häuser W, Katz RL et al (2016) Revisions to the 2010/2011 fibromyalgia diagnostic criteria. Semin Arthritis Rheum. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.08.012

Schmidt-Wilcke T, Clauw DJ (2011) Fibromyalgia: from pathophysiology to therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol 7:518–527. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrrheum.2011.98

Shipley M (2018) Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia syndrome. Medicine (UK) 46:252–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpmed.2018.01.009

Andrade A, Vilarino GT, Sieczkowska SM, Coimbra DR, de Steffens RAK, Vietta GG (2018) Acute effects of physical exercises on the inflammatory markers of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. J Neuroimmunol 316:40–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.12.007

Clauw DJ (2009) Fibromyalgia: an overview. Am J Med 122:s3-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.09.006

Andrade A, Vilarino GT, Sieczkowska SM, Coimbra DR, Bevilacqua GG, de Steffens RAK (2020) The relationship between sleep quality and fibromyalgia symptoms. J Health Psychol 25:1176–1186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317751615

Arnold LM, Bennett RM, Crofford LJ, Dean LE, Clauw DJ, Goldenberg DL et al (2019) AAPT diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Pain 20:611–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2018.10.008

Wolfe F, Schmukler J, Jamal S, Castrejon I, Gibson KA, Srinivasan S et al (2019) Diagnosis of fibromyalgia: disagreement between fibromyalgia criteria and clinician-based fibromyalgia diagnosis in a University Clinic. Arthritis Care Res 71:acr.23731. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.23731

Wolfe F, Ross K, Anderson J, Russell IJ, Hebert L (1995) The prevalence and characteristics of fibromyalgia in the general population. Arthritis Rheum 38:19–28. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780380104

Häkkinen A, Häkkinen K, Hannonen P, Alen M (2001) Strength training induced adaptations in neuromuscular function of premenopausal women with fibromyalgia: comparison with healthy women. Ann Rheum Dis 60:21–26. https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.60.1.21

Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, Atzeni F, Häuser W, Flub E et al (2017) EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis 76:318–328. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724

Andrade A, Dominski FH, Sieczkowska SM (2020) What we already know about the effects of exercise in patients with fibromyalgia: an umbrella review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 50:1465–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.02.003

Valim V, Natour J, Xiao Y, Pereira AFA, da Cunha Lopes BB, Pollak DF et al (2013) Effects of physical exercise on serum levels of serotonin and its metabolite in fibromyalgia: a randomized pilot study. Rev Bras Reumatol 53:538–541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbr.2013.02.001

Andrade A, Dominski FH (2021) Infographic. Effects of exercise in patients with fibromyalgia: an umbrella review. Br J Sports Med 55:279–280. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102330

Vilarino GT, Andreato LV, de Souza LC, Branco JHL, Andrade A (2021) Effects of resistance training on the mental health of patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Clin Rheumatol 40:4417–4425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-021-05738-z

Acosta-Gallego A, Ruiz-Montero PJ, Castillo-Rodríguez A (2018) Land- and pool-based intervention in female fibromyalgia patients: a randomized-controlled trial. Turk J Phys Med Rehabilit 64:337–343. https://doi.org/10.5606/tftrd.2018.2314

Moore GE, Durstine JL, Painter PL (2016) Others AC of SM and ACSM’s exercise management for persons with chronic diseases and disabilities. 4 ed

Andrade A, Vilarino GT, Bevilacqua GG (2017) What is the effect of strength training on pain and sleep in patients with fibromyalgia? Am J Phys Med Rehabil 96:889–893. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHM.0000000000000782

Assumpção A, Matsutani LA, Yuan SL, Santo AS, Sauer J, Mango P et al (2018) Muscle stretching exercises and resistance training in fibromyalgia: which is better? A three-arm randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabilit Med 54:663–670. https://doi.org/10.23736/s1973-9087.17.04876-6

Gavilán-Carrera B, Segura-Jiménez V, Mekary RA, Borges-Cosic M, Acosta-Manzano P, Estévez-López F et al (2019) Substituting sedentary time with physical activity in fibromyalgia and the association with quality of life and impact of the disease: the al-Ándalus project. Arthritis Care Res 71:281–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/ACR.23717

McLoughlin MJ, Stegner AJ, Cook DB (2011) The relationship between physical activity and brain responses to pain in fibromyalgia. JPain 12:640–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2010.12.004

Andrade A, de Steffens RAK, Vilarino GT, Sieczkowska SM, Coimbra DR (2017) Does volume of physical exercise have an effect on depression in patients with fibromyalgia? J Affect Disord 208:214–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.003

Sieczkowska SM, de Casagrande PO, Coimbra DR, Vilarino GT, Andreato LV, Andrade A (2019) Effect of yoga on the quality of life of patients with rheumatic diseases: systematic review with meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med 46:9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.07.006

Andrade CP, Zamunér AR, Forti M, França TF, Tamburús NY, Silva E (2017) Oxygen uptake and body composition after aquatic physical training in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 53:751–758. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04543-9

Jentoft ES, Grimstvedt Kvalvik A, Marit MA (2001) Effects of pool-based and land-based aerobic exercise on women with fibromyalgia/chronic widespread muscle pain. Arthritis Rheum 45:42–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200102)45:1%3c42::aid-anr82%3e3.3.co;2-1

Nichols DS, Glenn TM (1994) Effects of aerobic exercise on pain perception, affect, and level of disability in individuals with fibromyalgia. Phys Ther 74:327–332. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/74.4.327

Valim V, de Olsasl A, Natour J, Valim V, Oliveira L, Suda A, Silva L et al (2003) Aerobic fitness effects in fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 30:1060–1069

Ericsson A, Palstam A, Larsson A, Löfgren M, Bileviciute-Ljungar I, Bjersing J et al (2016) Resistance exercise improves physical fatigue in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 18:176. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-016-1073-3

Larsson A, Palstam A, Löfgren M, Ernberg M, Bjersing J, Bileviciute-Ljungar I et al (2015) Resistance exercise improves muscle strength, health status and pain intensity in fibromyalgia—a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-015-0679-1

Andrade A, de Azevedo-Klumb-Steffens R, Sieczkowska SM, Peyré Tartaruga LA, Torres-Vilarino G (2018) A systematic review of the effects of strength training in patients with fibromyalgia: clinical outcomes and design considerations. Adv Rheumatol 58:36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42358-018-0033-9

Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM, Potempa KM (2002) A randomized controlled trial of muscle strengthening versus flexibility training in fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 29:1041–1048

Matsutani LA, Marques AP, Ferreira EAG, Assumpção A, Lage LV, Casarotto RA et al (2007) Effectiveness of muscle stretching exercises with and without laser therapy at tender points for patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 25:410–415

Miguel G-H, Tomás G-I, Patricia M-M, Daniel P-M, Alejandro F-G, Francisco H-C et al (2020) Benefits of adding stretching to a moderate-intensity aerobic exercise programme in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabilit 34:242–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215519893107

Sañudo B, Galiano D, Carrasco L, Blagojevic M, De Hoyo M, Saxton J (2010) Aerobic exercise versus combined exercise therapy in women with fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 91:1838–1843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2010.09.006

Clark SR, Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Bennett R (2001) Exercise for patients with fibromyalgia: risks versus benefits. Curr Rheumatol Rep 3:135–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-001-0009-2

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, The PRISMA et al (2020) Statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ 2021:372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles M-A, Goldenberg DL, Katz RS, Mease P et al (2010) The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res 62:600–610. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.20140

Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ et al (2019) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327:557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. L. Erlbaum Associates

Izquierdo-Alventosa R, Inglés M, Cortés-Amador S, Gimeno-Mallench L, Chirivella-Garrido J, Kropotov J et al (2020) Low-intensity physical exercise improves pain catastrophizing and other psychological and physical aspects in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:3634. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103634

Tomas-Carus P, Gusi N, Häkkinen A, Häkkinen K, Leal A, Ortega-Alonso A (2008) Eight months of physical training in warm water improves physical and mental health in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 40:248–252. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0168

Gowans SE, deHueck A, Voss S, Silaj A, Abbey SE, Reynolds WJ (2001) Effect of a randomized, controlled trial of exercise on mood and physical function in individuals with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 45:519–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(200112)45:6%3c519::AID-ART377%3e3.0.CO;2-3

Valkeinen H, Alén M, Häkkinen A, Hannonen P, Kukkonen-Harjula K, Häkkinen K (2008) Effects of concurrent strength and endurance training on physical fitness and symptoms in postmenopausal women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89:1660–1666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.022

Häkkinen K, Pakarinen A, Hannonen P, Häkkinen A, Airaksinen O, Valkeinen H et al (2002) Effects of strength training on muscle strength, cross-sectional area, maximal electromyographic activity, and serum hormones in premenopausal women with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 29:1287–1295

Kayo AH, Peccin MS, Sanches CM, Trevisani VFM (2012) Effectiveness of physical activity in reducing pain in patients with fibromyalgia: a blinded randomized clinical trial. Rheumatol Int 32:2285–2292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-011-1958-z

Letieri RV, Furtado GE, Letieri M, Góes SM, Pinheiro CJB, Veronez SO et al (2013) Pain, quality of life, self-perception of health, and depression in patients with fibromyalgia treated with hydrokinesiotherapy. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia (English Edition) 53:494–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2013.04.004

Mengshoel AM, Komnaes HB, Forre O (1992) The effects of 20 weeks of physical fitness training in female patients with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 10:345–349

Munguía-Izquierdo D, Legaz-Arrese A (2007) Exercise in warm water decreases pain and improves cognitive function in middle-aged women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 25:823–830

Munguía-Izquierdo D, Legaz-Arrese A (2008) Assessment of the effects of aquatic therapy on global symptomatology in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 89:2250–2257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2008.03.026

Latorre-Román PÁ, Santos-E-Campos MA, García-Pinillos F (2015) Effects of functional training on pain, leg strength, and balance in women with fibromyalgia. Modern Rheumatol 25:943–947. https://doi.org/10.3109/14397595.2015.1040614

Sañudo B, Carrasco L, de Hoyo M, Figueroa A, Saxton JM (2015) Vagal modulation and symptomatology following a 6-month aerobic exercise programme for women with fibromyalgia. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33:S41–S45

Sañudo B, Galiano D, Carrasco L, De Hoyo M, McVeigh JG (2011) Effects of a prolonged exercise programe on key health outcomes in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 43:521–526. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0814

Andrade CP, Zamunér AR, Forti M, Tamburús NY, Silva E (2019) Effects of aquatic training and detraining on women with fibromyalgia: controlled randomized clinical trial. Eur J Phys Rehabilit Med 55:79–88. https://doi.org/10.23736/S1973-9087.18.05041-4

American College of Sports Medicine (2017) ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, 10th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH (2017) Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub2

Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, Webber SC, Musselman KE, Overend TJ et al (2019) Mixed exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013340

Bahadorfar M (2014) A Study of Hydrotherapy and Its Health Benefits. Int J Res 1:294–305

Hall J, Skevington SM, Maddison PJ, Chapman K (1996) A randomized and controlled trial of hydrotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 9:206–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/1529-0131(199606)9:3%3c206::AID-ANR1790090309%3e3.0.CO;2-J

Altan L, Bingöl U, Aykaç M, Koç Z, Yurtkuran M (2004) Investigation of the effects of pool-based exercise on fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheumatol Int 24:272–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00296-003-0371-7

McVeigh JG, McGaughey H, Hall M, Kane P (2008) The effectiveness of hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 29:119–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-008-0674-9

de Morton NA (2009) The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother 55:129–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0004-9514(09)70043-1

Häuser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, Moradi B, Steinbach M, Schiltenwolf M et al (2010) Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar3002

Busch AJ, Schachter CL, Overend TJ, Peloso PM, Barber KAR (2008) Exercise for fibromyalgia: a systematic review. J Rheumatol 35:1130–1144

Gowans SE, DeHueck A (2007) Pool exercise for individuals with fibromyalgia. Curr Opin Rheumatol 19:168–173. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e3280327944

Kisner C, Colby L, Borstad J (2017) Therapeutic exercise: foundations and techniques, 6th edn. FA Davis publication

Mannerkorpi K, Nyberg B, Ahlmen M, Ekdahl C (2000) Pool exercise combined with an education program for patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. A prospective, randomized study. J Rheumatol 27:2473–2481

Mccain GA, Bell DA, Mai FM, Halliday PD (1988) A controlled study of the effects of a supervised cardiovascular fitness training program on the manifestations of primary fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 31:1135–1141. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780310908

de Steffens RAK, Fonseca ABP, Liz CM, Araújo AVMB, da Viana MS, Andrade A (2012) Fatores associados à adesão e desistência ao exercício físico de pacientes com fibromialgia: uma revisão. Revista Brasileira de Atividade Física & Saúde 16:353–357. https://doi.org/10.12820/rbafs.v.16n4p353-357

Clark SR (1994) Prescribing exercise for fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Care Res 7:221–225. https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1790070410

Nørregaard J, Lykkegaard JJ, Mehlsen J, Danneskiold-Samsøe B (1997) Exercise training in treatment of fibromyalgia. J Musculoskelet Pain 5:71–79. https://doi.org/10.1300/J094v05n01_05

Tomas-Carus P, Gusi N, Häkkinen A, Häkkinen K, Raimundo A, Ortega-Alonso A (2009) Improvements of muscle strength predicted benefits in HRQOL and postural balance in women with fibromyalgia: an 8-month randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology 48:1147–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kep208

Valim V (2006) Benefícios dos exercícios físicos na fibromialgia. Rev Bras Reumatol 46:49–55. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0482-50042006000100010

Acknowledgements

Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology and Foundation for research and innovation support of the State of Santa Catarina

Funding

This work was supported by national funding through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under project UIDB/04045/2020 and by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 and FAPESC—Foundation for research and innovation support of the State of Santa Catarina—Grant number 2019031000035 and call number 04.2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: MLLA, DM, DAM and HPN. Data acquisition: MLLA and HPN. Analysis: MLA, DM, DAM, GTV, AA and HN. Interpretation of data for the work: MLLA, DM, GTV, AA and HPN. All authors drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published. All authors had agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors take full responsibility for the integrity of the study and the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albuquerque, M.L.L., Monteiro, D., Marinho, D.A. et al. Effects of different protocols of physical exercise on fibromyalgia syndrome treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int 42, 1893–1908 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05140-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-022-05140-1