Abstract

The effect of drawn orientation on crystalline fluorinated polymer/carbon nanotube nanohybrids was investigated. Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) were surface-modified with long-chain phosphonic acids, thus imparting heat-resistant/non-desorption properties. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) was used as the crystalline fluorinated polymer and a polypropylene (PP) matrix as the crystalline hydrogenated polymer, for comparison. In the nanocomposite preparation, PVDF was combined with phosphonic acid-modified SWCNT containing fluorocarbon chains, and PP was combined with phosphonic acid-modified SWCNT containing hydrocarbon chains. Nanocomposite preparations of organo-SWCNTs with an affinity for the polymer matrix were achieved by a simple melt-compound method. These nanocomposites were uniaxially drawn at high temperatures near its melting point, and the organo-SWCNTs were aligned in the polymer matrix along the drawn direction. The lamellae in the fluorinated polymer-based nanohybrids were aligned parallel to the drawn direction at 5 × drawing, and converted to a herringbone arrangement with a left–right tilting at 7 × to 9 × drawings. As a result, it was clarified that the addition of a small amount of SWCNT leads to an improvement of crystallinity, crystallization temperature, lamella thickness, and mechanical properties of the nanocomposites.

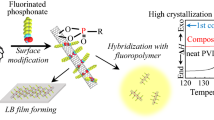

Graphic abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Controlling the structure on the nanometer level via the orientation effect has the potential to innovatively improve the physical properties of materials [1, 2]. Therefore, when rod-shaped, needle-shaped, and/or tubular nanofillers with a shape that has developed in the long-axis direction are oriented, it can be expected that a function that is specifically enhanced in the orientation direction is expressed [3, 4]. In the field of polymer composite materials [5, 6], single-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [7, 8] may be considered as one of these specially shaped nanofillers. Although the excellent functionalities of CNTs are too prominent and elaborate, they are allotropes of nanocarbon materials [9, 10], like fullerenes and graphenes. Further, the CNT is a single-layer or multi-layer coaxial tubular material made of a six-membered carbon-ring network/graphene sheet [11, 12]. Since there are too many reports on material development utilizing high conductivity, thermal conductivity, and heat resistance in addition to the morphological characteristics of thin, long, and flexible CNTs, it cannot be described here [13,14,15,16,17]. Active research on CNTs as inorganic nanofillers in nanocomposite medicine as well as in the field of polymer composites [18, 19] has raised a common problem in the extreme bundle-like aggregation of CNTs in the polymer matrix [20, 21]. Generally, the van der Waals interaction is remarkably enhanced between CNTs [22], and uniform dispersion in the matrix is difficult [23]. It is generally believed that polymer/inorganic nanofiller nanocomposite materials are enhanced in their physical properties by the uniform dispersion of nanofillers in the matrix [24]. In the highly aggregated state, the excellent physical properties peculiar to CNTs cannot be imparted to the nanocomposite material, and an increase in the ratio of CNTs is required to isolate the CNTs in the polymer. In addition, an aggregate structure of the CNTs that systematically faces a specific direction is required if the shape effect is sought [25].

The drawing effect on polymers is an effective method that can control the nanometer-dimensional structure from a size that can be handled on the centimeter level [26]. Macroscopic uniaxial drawing can orient lamellae in crystalline polymers and induce the formation of extended chain crystals [27, 28]. There is also a research example in which nanoparticles are oriented along the drawing direction in the matrix by drawing a composite material containing nanoparticles such as natural clay with a large aspect ratio [29]. Such a method also has the aspect that various physical properties such as mechanical and optical ones can be selectively enhanced along the orientation direction [30, 31]. In addition, there are various research examples on the free shrinkage after drawing, the use of fixed annealing, the use of biaxial drawing, and the correlation between the orientation structure and the functionality obtained by controlling the drawing temperature and magnification [32,33,34,35,36].

The shortcomings of CNTs include not only their remarkable tendency to aggregate, but also their persistence in the human body [37] and conversion to carcinogens [38]. Once introduced into the human body, CNTs are considered almost impossible to remove [39], and their retention in the lungs, analogous to asbestos, has been raised as a concern [40]. To effectively utilize CNTs, which are promising as a fossil resource [41], surface modification with organic matter reduces the likelihood of dusting/introducing into the human body and makes handling easier. Moreover, if the physical properties of the CNT can be utilized safely and to the maximum extent by a simple method, the applications of CNTs will be more widespread.

Previously, we proposed the application of a simple and efficient surface-modification method developed for nanodiamonds, which are allotropes of the same nanocarbon, to single-walled CNT (SWCNT), in addition to a prior hydrophilic treatment [42]. Furthermore, by modifying the SWCNT surface with a long-chain phosphonic acid, we achieved non-desorption/heat resistance organo-modification [43]. In addition, we have made strides toward nanocomposite preparations including organo-modified SWCNTs with crystalline polymers [44]. Moreover, a nanocomposite material using natural sepiolite clay as a special-shaped nanofiller was prepared [45] and its drawing orientation effect was clarified [46]. A nanofiller-containing nanocomposite with a shape that has developed along the major axis direction can achieve uniaxial drawing of the filler with enhanced physical properties along the drawn orientation.

Therefore, in this study, the orientation effect on the nanocomposite comprising fluorocarbon-modified SWCNT and crystalline fluoropolymer subjected to uniaxial drawing at high temperatures was evaluated. In addition, as a comparison, the nanocomposite consisting of hydrocarbon-modified SWCNT and general-purpose hydrogenated polymer was evaluated. Based on the results of this study, it was expected that this method can provide a new platform for the study of SWCNT filler addition in polymer-based nanocomposites (Fig. 1).

Materials and methods

Surface modification of SWCNT and nanocomposite preparation with matrix polymers

The SWCNT used in this study is a 5-nm-thick commercial product (ZEON NANO® SG101) provided by ZEON Nanotechnology Co. Ltd. and manufactured by the super-growth CVD method. The tube length has a distribution ranging from 100 to 600 nm (Fig. 2a). When this SWCNT is subjected to ultrasonic treatment in a mixed acid solution of sulfuric acid and nitric acid (3:1 for 24 h), the water-repellent surface is terminated with hydroxyl groups, becomes hydrophilic, and can be uniformly dispersed in an aqueous medium [42]. A toluene solution of 1H, 2H, 2H-perfluoro-n-decylphosphonic acid (FDPA, Fig. 2b) or stearyl phosphonic acid (ODPA, Fig. 2c) as a surface modifier was poured into an aqueous dispersion medium containing hydroxyl-terminated hydrophilic SWCNTs. At the water–oil interface, the positively charged terminal hydroxyl group and phosphonate anion undergo dehydration condensation, transferring protons to the adjacent functional groups to promote a positive surface charge. Furthermore, bidentate bonds of phosphonic acid were formed by dehydration condensation, which proceeded to modify the overall SWCNT surface with long-chain phosphonates. The modified organo-SWCNTs migrated to the oil layer, and the unreacted SWCNTs were removed together with the aqueous layer. The unreacted modifier was distilled off together with the solvent, and the resulting organo-modified SWCNTs were purified by washing away the small amount of unreacted material with a soluble solvent. Organo-SWCNTs obtained by hydrocarbon modification and fluorocarbon modification are abbreviated as ODP-SWCNTs and FDP-SWCNTs, respectively. The verification of the surface modification of these organo-SWCNTs and its characterization were performed by infrared spectroscopy. PVDF (provided by Kureha Co. Ltd., Mn = 280,000, Fig. 2d) was used as the matrix polymer for the nanocomposite. The melting point of PVDF is 174 °C. In previous studies [42,43,44,45,46], surface modification of SWCNT by FDPA was performed in the oil/water interface field. Toluene was poured into a water/methanol mixture of FDPA and SWCNT, and the fluorinated phosphonate-modified SWCNT obtained by the reaction was transferred to the oil phase. The aqueous phase and unreacted substances were removed, and FDP-SWCNT was purified and used. As comparison between hydrogenated and fluorinated crystalline polymers, polypropylene (PP, purchased from Prime Polymer Co. Ltd. Mn = 270,000) was used as a matrix (Fig. 2e). FDPA is tightly bound to the SWCNT surface via bidentate bonding of the phosphonic acid functional groups. Melt-compounding was performed at 200 °C for 5 min with a filler addition of 0.2 wt%. In addition, ODPA is also tightly bound to the SWCNT surface via bidentate bonding of the phosphonic acid functional groups. Melt-compounding was performed at 185 °C for 2 min with a filler addition of 0.5 wt% (Fig. 2f). The obtained nanocomposite was compression molded using a hot press and used for processing and measurements.

Drawing of neat polymers and polymer/long-chain phosphonate-modified SWCNT nanocomposites

Neat PVDF and a PVDF/fluorinated phosphonate-modified SWCNT nanocomposite were drawn uniaxially using a hand-drawing apparatus in an air oven at 154 °C. Further, neat PP and a PP/hydrogenated-modified SWCNT nanocomposite were also drawn uniaxially using a hand-drawing apparatus in an air oven at 139 °C (Fig. 2g). The surface of the film specimen was marked at intervals of 2 mm to measure the draw ratios. The drawing speed was fixed at 10 mm min–1, and the film was annealed at 154 or 139 °C for 5 min before drawing. The annealing temperature before drawing was set at 154 or 139 °C, which is exactly 20 °C below the melting point of the matrix polymer. To attain a constant condition, the crystalline polymers and their nanocomposites were cooled via immersion in water after drawing.

Morphological observation and structural estimation of nanohybrids including organo-modified SWCNT

The dispersion state of the organo-modified SWCNTs in the nanohybrid matrices was observed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (JEOL JEM-1400Plus) at an acceleration voltage of 120 kV. The nanohybrids, including the organo-SWCNT, were sliced into ultrathin sections approximately 100 nm in thickness using a Reichert ultramicrotome equipped with a diamond knife at room temperature. The sections were then transferred to a TEM grid for observation. The crystal structure and crystallinity of the nanohybrids were elucidated using high-performance wide-angle X-ray diffraction (WAXD) measurements (Bruker AXS, D8 ADVANCE) at 40 kV and 40 mA with rotating-anode Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) and a two-dimensional semiconductor detector. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on SII DSC6200 equipped with EXSTAR6000 controller. The scanning rate was 10 °C min–1. The spacing of the lamellae and the difference in the electron density between the crystalline and amorphous regions of the neat polymers and their nanohybrid were estimated by small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). The SAXS measurements (Nano-Viewer, Rigaku Co. Ltd.) were recorded at a tube current and voltage of 40 kV and 30 mA, respectively, with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.1542 nm). The mechanical properties of the neat polymers and their nanohybrids were evaluated by using tensile tests (Tensilon RTG1310, A&D Co. Ltd.) at a tensile speed of 10 mm min−1 and test-piece dumbbell punching at 23 °C.

Results and discussion

Change in crystallinity and crystallization temperature based on the SWCNT orientation in the matrices by high-temperature drawing

Nanocomposite preparations with a polymer can be achieved by introducing a hydrophilic functional group to SWCNT, which possess both water- and oil-repellent properties, by ultrasonic treatment with a mixed acid, and further introducing a hydrophobic organic molecular chain [43, 44]. Although it is difficult to introduce an amount of SWCNT into a polymer matrix, in general, heat-resistant phosphonate-modified SWCNTs can be nano-hybridized by a simple melt-compounding method. By substituting the modified chain with a fluorocarbon chain and imparting its affinity, it also becomes possible to introduce the organo-modified SWCNT into the fluoropolymer which has high phase-separated properties. However, as shown in the TEM image in upper part of Fig. 3, its dispersibility is not always sufficient. On the other hand, when this PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposite is subjected to high temperature drawing, not only is the nanofiller oriented in the drawing direction, but also its aggregation is relaxed (lower Fig. 3). From this TEM image, it was found that the needle-shaped nanofillers are arranged almost parallel to the drawn direction when subjected to 5 × drawing. The change in crystallinity and crystallization temperature to this orientation state is examined by the following measurements.

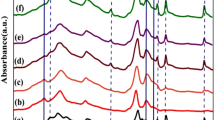

Figure 4 shows the change in WAXD profile with the draw ratio of the crystalline polymer/organo-modified SWCNT nanocomposite. In addition to the PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposite results (Fig. 4a), the measurement results for the PP/ODP-SWCNT nanocomposites (Fig. 4b) are also shown. In all cases, the WAXD vertical axis strength increased with the draw ratio. In the PVDF system, the diffraction peak intensities at the (100), (020), and (110) planes are remarkably improved, and in the PP system, the intensities of the (110), (040), and (130) diffraction peaks are conspicuously increased. On the other hand, in the PP system, the diffraction peak intensities of the plane indices (111) and (041) are significantly reduced due to the influence of orientation. To quantify these changes, the crystallinity was calculated and the results are shown in Table 1. In the PVDF system, the crystallinity increased remarkably during 2 × and 3 × drawing, but thereafter the change in the value was almost saturated. On the other hand, although the PP system exhibited a variation in this value, it does not show a remarkable improvement in the crystallinity after 2 × drawing. Further experimental data were collected in the form of the change in crystallization temperature by using DSC.

Here, the focus was the verification of the change in thermal behavior of the PVDF system. Figure 5a shows the draw ratio dependence of the PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposite in the DSC thermogram. In addition, Fig. 5b shows the draw ratio dependence of the DSC thermograms for neat PVDF. Focusing on the crystallization peaks during the 1st and 2nd cooling processes, the crystallization temperature gradually increased by 2.3 °C from the undrawn state to 153.2 °C after 5 × drawing. For the neat PVDF system, the crystallization temperature, which was 145.9 °C when undrawn, increased to 151.4 °C when stretched 3 ×, and increased by a further 0.4 °C when stretched 5 ×. The crystallization temperature of the undrawn PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposite was 150.9 °C, and the increase in the crystallization temperature of neat PVDF was 5.0 °C and 5.9 °C due to nanocomposite preparation and high-temperature drawing, respectively. Since the difference in crystallization temperature between neat PVDF and the PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposite after 5 × drawing was only 1.4 °C, it is expected that the change in thermal behavior for PVDF is more affected by high-temperature drawing than by nanocomposite preparation. However, a crystallization temperature of > 153 °C was achieved by the combination of composite preparation and high-temperature drawing. In general, the improvement of crystallization temperature reflects the thickening of the lamella, and thus in the next section, higher-order structural analyses using SAXS is presented.

Changes in lamella arrangement with high-temperature drawing of two kinds of nanocomposites containing SWCNT

Figure 6a shows the draw ratio dependence of the SAXS patterns and profiles for the PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposites. Circular scattering was confirmed in the undrawn sample, indicating an isotropic lamella arrangement. Two-point scattering of the 3 × and 5 × drawn samples indicated that the lamellae were arranged parallel to the drawing direction. Although the scattering image of the 9 × drawn sample appears to be a two-point image at first glance, the spot direction is upside down and a characteristic pattern that appears to be four-point image scatters combined with two-points was observed. This scattering image was seen equally for the 7 × or more drawn samples, and it was expected that the lamella formed a herringbone structure with a lateral tilt. This transition behavior is depicted in the illustration at the bottom of Fig. 6a. Although it was difficult to confirm the peak top at a relatively low intensity of the undrawn state in the SAXS profiles obtained by integrating these scattering images, the strength of the vertical axis increased drastically after 3 × drawing. At this time, the long period value increased by 3 nm or more, showing a value of 14.2 nm. After that, the intensity of the vertical axis decreased with the drawn ratio, and it remarkably decreased in the 9 × drawn sample. This behavior was also confirmed in the draw ratio dependence of SAXS for neat PVDF, which does not contain SWCNT (Fig. 6b). However, the decrease in the SAXS intensity after 9 × drawing is not clear compared to the corresponding SWCNT-containing nanocomposite. Since the intensity of the vertical axis of SAXS depends on the electron density difference in the measured sample, the density of the amorphous region becomes high when the composite is drawn by 9 ×, and it is considered that high-density amorphous regions are formed. In this regard, as a comparison, the draw ratio dependence of the SAXS patterns and profiles for PP/ODP-SWCNT nanocomposites is shown (Fig. 6c). Also in this case, when compared with the measurement results for neat PP (Fig. 6d), the composite system showed a marked decrease in the SAXS intensity after 3 × drawing. Therefore, it is considered that the density of the crystalline regions in the composite does not change greatly in both the fluorocarbon and hydrocarbon systems, and it is expected that the density of the amorphous regions will increase markedly with drawing. However, the appearance of voids is expected in hydrocarbon systems because clear void-scattering was observed in the SAXS patterns of the 3 × or more drawn samples. There may be a concern that defects in the PP-based composite are more likely to occur than in the fluorocarbon system. Here, since a significant difference in crystalline/amorphous electron densities was confirmed, precise analyses of the lamella was performed using a normalized one-dimensional electron density correlation function [46], calculated from the SAXS profiles (Fig. 7).

a SAXS patterns and b profiles with varying draw ratios of PVDF/fluorinated phosphonate-modified SWCNT nanocomposite. c SAXS profiles with varying draw ratios of neat PVDF. e SAXS patterns and f profiles with varying draw ratios of PP/hydrogenated phosphonate-modified SWCNT nanocomposite. g SAXS profiles with varying draw ratios of neat PP

Figure 7a shows a normalized one-dimensional electron density correlation function, K(z), obtained from the SAXS profiles of the PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanohybrid before and after drawing. From Fig. 6a, the long period value of the undrawn PVDF/FDP-SWCNT nanocomposite was 11.0 nm. This value corresponds to the distance between the centers of gravity of the lamella crystalline parts. The thickness of the lamella crystalline part and the distance between the lamella interfaces were calculated to be 3.0 and 7.6 nm, respectively. After 9 × drawing of this sample, the long period value expanded to 14.7 nm and the thickness of the lamella crystal part increased to 5.6 nm. Furthermore, the distance between the lamella interfaces increased to 13.4 nm, and the thickness of the amorphous part can be calculated to indicate that it is significantly larger than that of the crystalline part. From the remarkable decrease in the SAXS longitudinal intensity shown in Fig. 6a, it is expected that the density of the drawn amorphous region is considerably improved at this draw ratio.

Here, for comparison, the same analysis results for the PP-based nanocomposites containing SWCNTs are shown (Fig. 6b). Before and after 9 × drawing, the thickness of the lamella crystalline part increased from 4.7 to 6.3 nm. Furthermore, the distance between the lamella interfaces increased from 11.2 to 14.2 nm. The amorphous region is also drawn, and it is expected that the amorphous region will become rigid due to the decrease in SAXS intensity. However, changes in the amorphous region are not so remarkable as compared with the fluorocarbon polymer system. The reason for this tendency is probably related to the formation of a switch-board type lamella by the fluorinated polymers [47, 48], and fringed micelles [49] are easily formed by drawing. On the other hands, since the hydrocarbon-based general-purpose polymer forms lamella with a regular sharp folded chain [50,51,52], it seems that the transition to the fringed micelle structure is not remarkable.

Nanocarbon orientation effect on mechanical property enhancement accompanying high-temperature drawing of crystalline polymer/organo-modified SWCNT nanocomposites

Based on the structural analysis results of the draw-oriented crystalline polymer/organo-modified SWCNT nanocomposites thus far, the mechanical properties were evaluated by a tensile test (Fig. 8 and Table 2). As shown in the stress–strain (S–S) curves in Fig. 8a, the Young's modulus and maximum stress value of the PVDF-based nanocomposite including SWCNT increased with the draw ratio. Here, the tensile evaluation of the 9 × drawn sample lacked quantitative estimation because of the constraint of the macroscopic sample preparation. Therefore, the maximum stretch ratio sample was set to 7 ×. The S–S curve measurement was also performed for neat PVDF in order to separately consider the effect of drawn-orientation and the orientation effect of organo-modified SWCNTs. Due to the orientation effect of SWCNT, higher values of the Young's modulus and maximum stress calculated from the initial gradient were detected in the nanocomposite. In particular, when drawn at 5 ×, the difference in the Young's modulus between the two exceeded 1000 MPa. However, more remarkable is the difference in behavior of the strain axis on the horizontal axis. The strain value exceeded 30 to 40% due to the drawing and nanocomposite preparation, and not only did the stress value withstand rupture increases but the sample also exhibited excellent “elongation” characteristics. This behavior seems to be due to the development of the amorphous region clarified during the SAXS analyses. It is expected that the thickening of the crystalline region by drawing improves the maximum stress and the Young's modulus, while the formation of rigid and dense amorphous regions improves the elongation properties of the sample.

Figure 8c and d shows the draw ratio dependence of the S–S curves of the PP/ODP-SWCNT nanocomposite and neat PP. From the various parameters related to mechanical properties shown in Table 2, it can be seen that the increase in the Young's modulus and the maximum stress are more remarkable than in the PVDF system. On the other hand, the change in the abscissa value seen in the PVDF system can hardly be confirmed. This result also corresponds to the results of the SAXS analyses of the corresponding sample. In the PP system, the effect of the crystalline region clearly manifested in the change in mechanical properties, and the effect of the amorphous region is minor.

The above results are summarized in Fig. 9. The interesting effect confirmed in this study was that the orientation effect of the fluorinated phosphonate-modified SWCNT in the fluorinated polymer promoted the densification of the amorphous region in the polymer matrix and affected the elongation properties of the sample. The SWCNTs whose surface was modified with fluorocarbon and had an affinity for fluorinated polymers were arranged in the same direction as the lamella orientation in the fluoropolymer matrix without phase separation, by drawn-orientation. It was found that the changes in crystallinity and crystallization temperature were more affected by high-temperature drawing than by nanocomposite preparation. On the other hand, the effect on the amorphous region was significantly shown by the orientation effect of SWCNT, and the maximum value of a physical property was always recorded in the drawn-oriented nanocomposite containing SWCNT. However, considering the excellent physical properties of SWCNTs, the effect of drawn and oriented SWCNTs on the physical properties of nanohybrid material was somewhat disappointing. The reason for this result might be the initial dispersion state when preparing the nanocomposite. TEM observations showed that high-temperature uniaxial drawing had the effect of relaxing the aggregation of particles in the matrix. If the dispersion state was already improved at the nanocomposite preparation stage, the drawing orientation effect will be more remarkable. As the next approach, we aim to prepare well-dispersed SWCNT-containing nanocomposites by mixing a trace amount of a third component. As shown in Fig. S1, even under the adjusted conditions in which the modified SWCNTs introduced into the PP matrix remarkably aggregated, the dispersion state can be innovatively improved by adding a small amount of the modifier alone. This experimental finding is due to the extremely high sublimation temperature of long-chain phosphonic acid, and since it exists in the solid phase up to the melting point of PP or higher, it is possible to adjust the nanohybridization in a ternary system. In the next progress of this research, we aim to clarify the effect of the drawn orientation on such uniformly dispersed nanocomposites.

Conclusions

The effect of drawn orientation at high temperatures on crystalline fluorinated polymer/carbon nanotube nanohybrids was investigated. SWCNTs were surface-modified with a long-chain phosphonic acid, thus imparting heat resistance/non-desorption properties, and suppressing dusting and high-level aggregation. In the preparation of the nanocomposites, fluorocarbon-modified SWCNTs, which have an affinity for phase-separable fluorinated polymers, were added to achieve nanocomposite formation by melt-compounding. The nanocomposite was uniaxially drawn at high temperatures near its melting point and the organo-modified SWCNTs were found to orient along the drawn direction in the polymer matrix. The fluorinated polymer-based nanohybrid lamellae were arranged parallel to the drawn direction like SWCNTs after 5 × drawing, and the lamellae were transferred to the herringbone arrangement on the left and right when drawn at 7 × or more. Drawn-oriented nanohybrids have increased crystallinity, crystallization temperature, lamella thickness, and increased density in the amorphous regions. As a result, it was confirmed that the mechanical properties were enhanced by an increase in the crystalline region, and the elongation property was improved by the densification of the amorphous region.

References

Koziol K, Vilatela J, Moisala A, Motta M, Cunniff P, Sennett M, Windle A (2007) High-performance carbon nanotube fiber. Science 318:1892

Roach P, Farrar D, Perry CC (2006) Surface tailoring for controlled protein adsorption: effect of topography at the nanometer scale and chemistry. J Am Chem Soc 128:3939

Zhang XM, Zhang JJ, Xia LC, Li CH, Wang JF, Xu F, Zhang XL, Wu H, Guo SY (2017) Simple and consecutive Melt extrusion method to fabricate thermally conductive composites with highly oriented boron nitrides. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9:22977

Guin T, Kowalski BA, Rao R, Auguste AD, Grabowski CA, Lloyd PF, Tondiglia VP, Maruyama B, Vaia RA, White TJ (2018) Electrical control of shape in voxelated liquid crystalline polymer nanocomposites. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 10:1187

Kalaj M, Denny MS, Bentz KC, Palomba JM, Cohen SM (2019) Nylon–MOF composites through postsynthetic polymerization. Angew Chem Int Ed 58:2336

Liu PJ, Yao ZJ, Li L, Zhou JT (2016) In situ Synthesis and mechanical, thermal properties of polyimide nanocomposite film by addition of functionalized graphene oxide. Polym Compos 37:907

Desai SB, Madhvapathy SR, Sachid AB, Llinas JP, Wang QX, Ahn GH, Pitner G, Kim MJ, Bokor J, Hu CM, Wong HSP, Javey A (2016) MoS2 transistors with 1-nanometer gate lengths. Science 354(6308):99–102

Zhang CF, Anasori B, Seral-Ascaso A, Park SH, McEvoy N, Shmeliov A, Duesberg GS, Coleman JN, Gogotsi Y, Nicolosi V (2017) Transparent, flexible, and conductive 2D titanium carbide (MXene) films with high volumetric capacitance. Adv Mater 29:1702678

Santos NF, Cicuendez M, Holz T, Silva VS, Fernandes KJS, Vila M, Costa FM (2017) Diamond-graphite nanoplatelet surfaces as conductive substrates for the electrical stimulation of cell functions. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9:1331

Kawamoto M, He P, Ito Y (2017) Green processing of carbon nanomaterials. Adv Mater 29:1602423

Xu PD, Xie RX, Liu YP, Luo GA, Ding MY, Liang QL (2019) Bioinspired microfibers with embedded perfusable helical channels. Adv Mater 29:1701664

Ma CR, Li X, Deng CJ, Hu YY, Lee S, Liao XZ, He YS, Ma ZF, Xiong H (2019) Coaxial carbon nanotube supported TiO2@ MoO2@ carbon core–shell anode for ultrafast and high-capacity sodium ion storage. ACS Nano 13:671

Guan XY, Zheng GQ, Dai K, Liu CT, Yan XR, Shen CY, Guo ZH (2016) Carbon nanotubes-adsorbed electrospun PA66 nanofiber bundles with improved conductivity and robust flexibility. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 8:14150

Xeng XL, Sun JJ, Yao YM, Sun R, Xu JB, Wong CP (2017) A combination of boron nitride nanotubes and cellulose nanofibers for the preparation of a nanocomposite with high thermal conductivity. ACS Nano 11:5167

Song PG, Dai JF, Chen GR, Yu YM, Fang ZP, Lei WW, Fu SY, Wang H, Chen ZG (2018) Bioinspired design of strong, tough, and thermally stable polymeric materials via nanoconfinement. ACS Nano 12(9):9266–9278

Duduta M, Wood RJ, Clarke DR (2016) Multilayer dielectric elastomers for fast, programmable actuation without prestretch. Adv Mater 28:8058

Min H, Kim YT, Moon SM, Han JH, Yum K, Lee CY (2019) High‐yield fabrication, activation, and characterization of carbon nanotube ion channels by repeated voltage‐ramping of membrane‐capillary assembly. Adv Funct Mater 29:1900421

Zhao YH, Tang JJ, Motavalizadehkakhky A, Kakooei S, Sadeghzadeh SM (2019) Synthesis and characterization of a novel CNT-FeNi3/DFNS/Cu(ii) magnetic nanocomposite for the photocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in wastewater. RSC Adv 9:35022

Vannozzi L, Gouveia P, Pingue P, Canale C, Ricotti L (2020) Novel ultrathin films based on a blend of PEG-b-PCL and PLLA and doped with ZnO nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 12:21398

Pramanik C, Gissinger JR, Kumar S, Heinz H (2017) Carbon nanotube dispersion in solvents and polymer solutions: mechanisms, assembly, and preference. ACS Nano 11:12805

Gaikwad PV, Sharma SK, Sudarshan K, Kumar V, Kshirsagar A, Pujari PK (2018) Molecular packing of polyvinyl alcohol in PVA‐gold nanoparticles composites and its role on thermo‐mechanical properties. Polym Compos 39:1137

Mallakpour S, Soltanian S (2016) Surface functionalization of carbon nanotubes: fabrication and applications. RSC Adv 6:109916

Fukumaru T, Fujigaya T, Nakashima N (2013) Mechanical reinforcement of polybenzoxazole by carbon nanotubes through noncovalent functionalization. Macromolecules 46:4034

Subramani NK, Nagaraj SK, Shivanna S, Siddaramaiah H (2016) Highly flexible and visibly transparent poly (vinyl alcohol)/calcium zincate nanocomposite films for UVA shielding applications as assessed by novel ultraviolet photon induced fluorescence quenching. Macromolecules 49:2791

Hwang JY, Kim HS, Kim JH, Shin US, Lee SH (2015) Carbon nanotube nanocomposites with highly enhanced strength and conductivity for flexible electric circuits. Langmuir 31:7844

Shabahang S, Tao G, Kaufman JJ, Qiao Y, Wei L, Bouchenot T, Gordon AP, Fink Y, Bai Y, Hoy RS, Abouraddy AF (2016) Controlled fragmentation of multimaterial fibres and films via polymer cold-drawing. Nature 534:529

Li L, Hu J, Li Y, Huang Q, Sun X, Yan S (2020) Evidence for the soft and hard epitaxies of poly (l-lactic acid) on an oriented polyethylene substrate and their dependence on the crystallization temperature. Macromolecules 53:1745

Li H, Liu D, Bu X, Zhou Z, Ren Z, Sun X, Reiter R, Yan S, Reiter G (2020) Formation of asymmetric leaf-shaped crystals in ultrathin films of oriented polyethylene molecules resulting from high-temperature relaxation and recrystallization. Macromolecules 53:346

Wang KH, Xu M, Choi YS, Chung IJ (2001) Effect of aspect ratio of clay on melt extensional process of maleated polyethylene/clay nanocomposites. Polym Bull 46:499

Krause S, Neumann M, Fröbe M, Magerle R, von Borczyskowski C (2016) Monitoring nanoscale deformations in a drawn polymer melt with single-molecule fluorescence polarization microscopy. ACS Nano 10:1908

Boersma A, van Turnhout J, Wübbenhorst M (1998) Dielectric characterization of a thermotropic liquid crystalline copolyesteramide: 2. Orientation and crystallinity. Macromolecules 31:7461

Chae S, Lee JP, Kim JM (2016) Mechanically drawable thermochromic and mechanothermochromic polydiacetylene sensors. Adv Funct Mater 26:1769

Deng H, Skipa T, Bilotti E, Zhang R, Lellinger D, Mezzo L, Fu Q, Alig I, Peijs T (2010) Preparation of high‐performance conductive polymer fibers through morphological control of networks formed by nanofillers. Adv Funct Mater 20:1424

de Kort GW, Rastogi S, Wilsens CHRM (2019) Controlling processing, morphology, and mechanical performance in blends of polylactide and thermotropic polyesters. Macromolecules 52:6005

Wilsens CHRM, Pepels MPF, Spoelstra AB, Portale G, Auhl D, Deshmukh YS, Harings JAW (2016) Improving stiffness, strength, and toughness of poly (ω-pentadecalactone) fibers through in situ reinforcement with a vanillic acid-based thermotropic liquid crystalline polyester. Macromolecules 49:2228

Hassan MK, Cakmak M (2015) Strain-induced crystallization during relaxation following biaxial stretching of PET films: a real-time mechano-optical study. Macromolecules 48:4657

Reshma SC, Syama S, Mohanan PV (2016) Nano-biointeractions of PEGylated and bare reduced graphene oxide on lung alveolar epithelial cells: a comparative in vitro study. Colloids Surf B 140:104

Lee DK, Jeon S, Han Y, Kim SH, Lee S, Yu IJ, Song KS, Kang A, Yun WS, Kang SM, Huh YS, Cho WS (2018) Threshold rigidity values for the asbestos-like pathogenicity of high-aspect-ratio carbon nanotubes in a mouse pleural inflammation model. ACS Nano 12:10867

Chen G, Liu D, He C, Gannett TR, Lin W, Weizmann Y (2015) Enzymatic synthesis of periodic DNA nanoribbons for intracellular pH sensing and gene silencing. J Am Chem Soc 137:3844

Kinaret P, Ilves M, Fortino V, Rydman E, Karisola P, Lahde A, Koivisto J, Jokiniemi J, Wolff H, Savolainen K, Greco D, Alenius H (2017) Inhalation and oropharyngeal aspiration exposure to rod-like carbon nanotubes induce similar airway inflammation and biological responses in mouse lungs. ACS Nano 11:291

Wang J, Kaskel S (2012) KOH activation of carbon-based materials for energy storage. J Mater Chem 22:23710

Hirayama S, Abiko Y, Machida H, Fujimori A (2019) Application of a simple and highly efficient nanoparticle surface modification method to single-walled carbon nanotubes and formation of an interfacial organized film. Thin Solid Films 685:168

Abiko Y, Hayasaki T, Hirayama S, Almarasy AA, Kawabata Y, Fujimori A (2020) Formation, structure, and function of hydrogenated and fluorinated long-chain phosphonate-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes with bidentate bonds. ChemistrySelect. https://doi.org/10.1002/slct.202001535

Abiko Y, Hayasaki T, Hirayama S, Almarasy AA, Fujimori A (2020) Attempt of uniform dispersion in polymer-based nanocomposites using surface-modified single-walled carbon nanotubes. Polym Bull. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-020-03180-w

Hirayama S, Hayasaki T, Okano R, Fujimori A (2020) Preparation of polymer‐based nanocomposites composed of sustainable organo‐modified needlelike nanoparticles and their particle dispersion states in the matrix. Polym Eng Sci 60:541

Hirayama S, Hayasaki T, Almarasy AA, Yabu H, Tokita M, Fujimori A (2020) Influence of uniaxial orientation of fluorinated polymer/phosphonate-modified needle-like nanofiller composite by drawing. Polym Compos. https://doi.org/10.1002/PC.25598

Flory PJ (1962) On the morphology of the crystalline state in polymers. J Am Chem Soc 84:2857

Fujimori A, Hayasaka Y (2008) Changes in arrangement of lamella and fine crystallite in fluorinated “crystalline” transparent fibers with drawing. Macromolecules 41:7606

Li LS, Zhou F, Li YW, Chen XF, Zhang ZB, Zhou NC, Zhu XL (2018) Cooperation of amphiphilicity and smectic order in regulating the self-assembly of cholesterol-functionalized brush-like block copolymers. Langmuir 34:11034

Keller A (1957) A note on single crystals in polymers: evidence for a folded chain configuration. Philos Mag 2:1171

Till PH (1957) The growth of single crystals of linear polyethylene. J Polym Sci 24:301

Fischer EWZ (1957) Stufen- und spiralförmiges kristallwachstum bei hochpolymeren. Naturforschung 12(a):753

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “MSF Materials Science (Grant No. JP 19H05118)”. Further, authors also thank Mr. M. Yajima, ZEON Nanotechnology Co. Ltd., for the providing of carbon nanotube samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supporting Information

This material is available free of charge via the Internet at https://www.springer.com/journal/289 (PDF 153 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hayasaki, T., Abiko, Y., Almarasy, A.A. et al. Effect of the uniaxial orientation on the polymer/filler nanocomposites using phosphonate-modified single-walled carbon nanotube with hydro- or fluorocarbons. Polym. Bull. 78, 5503–5524 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-020-03388-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-020-03388-w