Abstract

Purpose

Although irinotecan monotherapy is often used in third-line treatment after the failure of taxanes in Japanese clinical practice, its survival benefit is still unclear. The aim of this study is to investigate the efficacy and safety of irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment.

Methods

Clinical data from consecutive patients in whom irinotecan had been initiated as third-line treatment between December 2003 and July 2015 in Shizuoka Cancer Center were retrospectively analyzed. Patients who were refractory or intolerant to fluoropyrimidine with or without platinum in first-line treatment and subsequent therapy with taxanes were included in this study. Irinotecan was administered at 150 mg/m2 every 2 weeks.

Results

The data of 50 patients who met the inclusion criteria were analyzed. The overall response rate was 18.4 % (7/38) among the patients with measurable disease. The median progression-free survival time was 66 days, and the median survival time was 180 days from the initiation of irinotecan therapy. The major grade 3 or 4 adverse events including neutropenia, fatigue, and anorexia were observed in 12 (24 %), 8 (16 %), and 7 (14 %), respectively. No treatment-related deaths occurred. Thirteen patients (26 %) required a dose reduction to 120 mg/m2 or less from the initiation of irinotecan.

Conclusions

This study suggests that irinotecan as third-line treatment has an anti-tumor effect and is feasible with optimal dose modification for advanced gastric cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. This is also the case in Japan, where 47,903 patients died of this disease in 2014 [2]. The only treatment option for unresectable advanced gastric cancer (AGC) is chemotherapy. Fluoropyrimidine plus platinum doublet therapy is a standard first-line treatment not only in Japan but in worldwide based on the results of the JCOG 9912 trial and SPIRITS trial [3, 4]. Although the standard treatment after the failure of first-line treatment has not been established, several clinical trials demonstrated a survival benefit of second-line treatment for AGC compared with best supportive care (BSC) [5–8].

In the WJOG 4007 trial, a randomized phase 3 trial conducted in Japan and there was a tendency for better overall survival (OS) and a better safety profile for paclitaxel than for irinotecan, as second-line treatment in patients with AGC [9]. Furthermore, in a randomized phase 3 trial (RAINBOW trial), the combination chemotherapy of ramucirumab plus paclitaxel as second-line treatment prolonged OS compared with placebo plus paclitaxel [hazard ratio (HR), 0.807, 95 % confidence interval (CI), 0.678–0.962] [10]. Thus, ramucirumab plus paclitaxel doublet therapy is currently regarded as the standard treatment in a second-line setting [11].

Third-line treatment of AGC is expected to be developed in the near future; therefore, it is important to evaluate the survival benefit of third-line treatment. After WJOG 4007 trial [9] and RAINBOW trial [10], taxanes are used in second-line treatment, and irinotecan is more often used for third-line treatment in Japanese clinical practice. It is thought to be a problem that irinotecan monotherapy is deemed as standard treatment in third-line setting without elucidating its efficacy and safety sufficiently. Thus, we investigated the efficacy and safety of irinotecan as third-line treatment for AGC.

Materials and methods

Patients

The subjects were patients with AGC treated with irinotecan monotherapy in a third-line setting between December 2003 and July 2015 at the Shizuoka Cancer Center, Shizuoka, Japan. All data were retrospectively collected from electronic medical records. All procedures were in accordance with institutional and national standards on human experimentation, as confirmed by the ethics committee of Shizuoka Cancer Center, and also with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent was obtained from all of the study participants. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) age of 75 years or less; (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 2 or less; (3) histologically proven metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma; (4) refractory or intolerant to fluoropyrimidines (fluorouracil, S-1, or capecitabine) or fluoropyrimidines plus platinum (cisplatin or oxaliplatin) in a first-line setting; (5) refractory or intolerant to taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel, or nab-paclitaxel) in a second-line setting; (6) no prior chemotherapy with irinotecan; (7) adequate organ function [neutrophils ≥1500/µL, platelets ≥100,000/µL, bilirubin ≤1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), aspartate aminotransferase ≤3.0 times ULN, alanine aminotransferase ≤3.0 times ULN]; (8) no other synchronous advanced cancer or other serious disease; and (9) without massive ascites. If ascites was confirmed in consecutive slices on computed tomography or ultrasonography from liver to pelvis, it was defined as massive ascites. All patients provided written informed consent before the start of treatment.

Treatment

The approved dose of irinotecan in Japan is 150 mg/m2 every 2 weeks. Therefore, irinotecan was started at 150 mg/m2 in 250 ml of 5 % glucose solution by intravenous infusion in 90 min, which was repeated every 2 weeks as one course. Treatment was repeated until disease progression, the occurrence of unacceptable toxicity, or the patient’s refusal to continue. In cases of severe toxicity, treatment was suspended until recovery. The dose of irinotecan was reduced to 120 or 100 mg/m2 depending on the toxicity or a physician’s judgment in any course. Dose intensity was calculated by dividing the total dose of drug by the duration of treatment.

Evaluation

Therapeutic effect was assessed approximately every 2 months using computed tomography, tumor markers, and clinical manifestations. Tumor response was evaluated by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST 1.1) [12]. Symptomatic toxicity and laboratory data were monitored at least every 2 weeks. Toxicity was graded by the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.0).

Statistical analysis

OS was calculated from the date of initiation of irinotecan until death. Patients who were alive or for whom data were missing at the data cutoff were censored. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of initiation of irinotecan until progressive disease was confirmed. Patients for whom there was no information regarding progression were treated as censored cases. OS and PFS were estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method. All analyses were conducted using EZR statistical software, version 1.30 [13]. Efficacy analyses were performed by intention-to-treat. Safety analyses included all patients who received at least one dose of irinotecan.

Results

Between December 2003 and July 2015, 79 patients were administered irinotecan as third-line treatment. Among them, 50 patients met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed (Fig. 1). Their characteristics are shown in Table 1. Forty patients (80 %) had an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1. Eighteen patients (36 %) had undergone gastrectomy, and 19 patients (38 %) had suffered mild or moderate ascites. As first-line treatment, fluoropyrimidine plus platinum had been administered in 45 patients (90 %) and fluoropyrimidine alone in 5 patients (10 %). As second-line treatment, paclitaxel had been administered in 45 patients (90 %), nab-paclitaxel in 3 patients (6 %), and docetaxel in 2 patients (4 %).

Efficacy

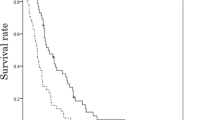

Thirty-eight patients with measurable lesions were evaluated for tumor response. Seven of these showed a partial response (Table 2), yielding a response rate (RR) of 18.4 % and a disease control rate (DCR: partial response and stable disease) of 55.2 %. Overall, 14 patients (36.8 %) experienced shrinking of the measurable lesion (Fig. 2). The median follow-up time was 191 days in censored cases, as of the cutoff date of March 29, 2016. The median PFS was 66 days (95 % CI 49–112) (Fig. 3), and the median OS was 180 days (95 % CI 133–241) (Fig. 3).

Safety

The hematological and non-hematological toxicities encountered are shown in Table 3. As for grade 3 or 4 hematological toxicities, anemia occurred in 15 patients (30 %), leukopenia in 12 (24 %), neutropenia in 12 (24 %), and thrombocytopenia in 1 (2 %). As for grade 3 or 4 non-hematological toxicities, fatigue occurred in 8 patients (16 %), anorexia in 7 (14 %), diarrhea in 4 (8 %), and febrile neutropenia in 3 (6 %). No treatment-related deaths occurred.

Treatment exposure

The median number of courses per patient was four (1–32). Thirteen patients required a dose reduction to 120 mg/m2 or less from the initiation of irinotecan, as judged necessary by a physician. Sixteen patients required a dose reduction in a subsequent course: because of grade 3 or 4 gastrointestinal toxicity (diarrhea, nausea, vomiting) in ten patients, fatigue in four, grade 3 neutropenia in three, and as judged necessary by a physician in two.

The median dose intensity was 56.3 mg/m2/week, which corresponded to 78 % of the standard dose. A dose reduction by 20 % of baseline dose was required in 23 patients, and by over 20 % in 6 patients. The treatment was discontinued in 49 patients: due to disease progression in 48 patients and death due to another disease in 1.

Twenty patients (40 %) received subsequent chemotherapy after the failure of treatment with irinotecan. Fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy was administered in 13 patients (26 %) and taxanes in 5 (10 %) (Table 4).

Discussion

Some reports have been published about the outcome of third-line treatment for AGC [14–16]. We previously reported the efficacy and safety of weekly paclitaxel for AGC in a third-line setting and suggested that third-line treatment for AGC had anti-tumor activity [14]. A retrospective study in Korea also suggested that biweekly FOLFIRI regimen including irinotecan as third-line treatment might have survival benefit: OS and PFS were 5.6 and 2.1 months, respectively, and RR was 9.6 % [16]. In Japan, although irinotecan is commonly used as third-line treatment in clinical practice based on the results of the WJOG 4007 trial, the treatment outcome of irinotecan monotherapy in a third-line setting is still unclear. Therefore, we investigated the efficacy and safety of irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment. In terms of the efficacy, the RR and survival time in this study were similar to those in previous studies in a second-line setting [17, 18]. Ten patients achieved a PFS of over 180 days; however, we could not identify any predictive markers of increased survival. Considering that the OS in the BSC group after second-line treatment was only 2.4 to 4.3 months in previous clinical trials [5–8, 19] and the survival time of our study was longer than that of Korean study [16], irinotecan monotherapy might be regarded as an available treatment option for AGC in a third-line setting. While 57 % of study participants in that Korean study were needed initial dose reduction, 26 % were needed in this study [16]. Irinotecan monotherapy may be more feasible regimen probably because FOLFIRI regimen is a burden for patients in salvage line.

The most common adverse event in this study was anemia, probably because the study participants had undergone intensive treatment and many of them had primary lesions that might cause occult bleeding. Indeed, 46 of 50 patients had suffered severe anemia of grade 1 or more before the initiation of irinotecan. Worsening of anemia by over one grade compared with that at baseline occurred in 29 patients; however, anemia was not related to the discontinuation of irinotecan. The incidences of anorexia and fatigue were higher than in previous studies [17, 18], probably because more AGC patients in a third-line setting had peritoneal dissemination or ascites. Adverse events were manageable because the incidence of such events was generally consistent with those in previous reports [17, 18] and no treatment-related deaths occurred. However, four patients died due to disease progression within 30 days of the final dosage of irinotecan. The selection of patients who are suitable for chemotherapy in a third-line setting seems to be necessary because chemotherapy can worsen the quality of life and shorten overall survival in some cases.

Now that evidence for first and second-line standard treatments has been established, the development of chemotherapy regimens after a second-line setting is anticipated. A phase 3 study in China, which compared the efficacy and safety of apatinib with those of a placebo, showed a survival benefit in third-line treatment: OS and PFS were 6.5 months (HR 0.709; 95 % CI 0.537–0.937) and 2.6 months (HR 0.444; 95 % CI 0.331–0.595), respectively, and RR was 2.84 % [15]. This is the first phase 3 study demonstrating the survival benefit of a vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-targeted drug as third-line treatment. The OS and PFS associated with apatinib administration were similar to those in our study. In addition, while apatinib is currently available only in China, irinotecan can be used worldwide. Therefore, the development of irinotecan-based regimens may be preferable. In fact, a clinical trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of irinotecan plus ramucirumab compared with those of irinotecan monotherapy is now being planned in Japan. Furthermore, a phase 3 study to investigate the effect of avelumab, an immune-checkpoint inhibitor, compared with the physician’s choice (irinotecan, paclitaxel, or BSC) in AGC patients for whom second-line treatment failed is ongoing (NCT02625623). The results of the current study may thus be useful as reference data for these new clinical trials.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, the fact that it was performed in a single institution, its small sample size, and its potential for selection bias. In addition, the general condition of patients who are able to receive third-line treatment is usually favorable: They might thus be more sensitive to chemotherapy.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report the efficacy and safety of irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment for patients who are intolerant or refractory to standard treatment. Irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment might have an anti-tumor effect and is feasible with optimal dose modification for advanced gastric cancer.

References

Ferlay J SI, Ervik M, et al. GLOBOCAN 2012 v1.0, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: IARC CancerBase No. 11. Lyon, France: International agency for research on Cancer; 2013. http://globocan.iarc.fr (accessed Oct 7, 2015)

Statistics and Information Department MoH, Labour and Welfare. Vital statistics in 2014 (in Japanese). http://www.mhlwgojp/Accessed 1 Nov 2015

Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T et al (2008) S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol 9:215–221. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(08)70035-4

Boku N, Yamamoto S, Fukuda H et al (2009) Fluorouracil versus combination of irinotecan plus cisplatin versus S-1 in metastatic gastric cancer: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 10:1063–1069. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(09)70259-1

Thuss-Patience PC, Kretzschmar A, Bichev D et al (2011) Survival advantage for irinotecan versus best supportive care as second-line chemotherapy in gastric cancer–a randomised phase III study of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie (AIO). Eur J Cancer 47:2306–2314. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.002

Kang JH, Lee SI, Lim do H et al (2012) Salvage chemotherapy for pretreated gastric cancer: a randomized phase III trial comparing chemotherapy plus best supportive care with best supportive care alone. J Clin Oncol 30:1513–1518. doi:10.1200/jco.2011.39.4585

Ford HE, Marshall A, Bridgewater JA et al (2014) Docetaxel versus active symptom control for refractory oesophagogastric adenocarcinoma (COUGAR-02): an open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 15:78–86. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70549-7

Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ et al (2014) Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 383:31–39. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)61719-5

Hironaka S, Ueda S, Yasui H et al (2013) Randomized, open-label, phase III study comparing irinotecan with paclitaxel in patients with advanced gastric cancer without severe peritoneal metastasis after failure of prior combination chemotherapy using fluoropyrimidine plus platinum: WJOG 4007 trial. J Clin Oncol 31:4438–4444. doi:10.1200/jco.2012.48.5805

Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E et al (2014) Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 15:1224–1235. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(14)70420-6

NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Gastric Cancer v.3 2015, accessed Nov 9, 2015, at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

Kanda Y (2013) Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 48:452–458. doi:10.1038/bmt.2012.244

Shimoyama R, Yasui H, Boku N et al (2009) Weekly paclitaxel for heavily treated advanced or recurrent gastric cancer refractory to fluorouracil, irinotecan, and cisplatin. Gastric Cancer 12:206–211. doi:10.1007/s10120-009-0524-9

Li J, Qin S, Xu J et al (2016) Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Trial of Apatinib in Patients With Chemotherapy-Refractory Advanced or Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Stomach or Gastroesophageal Junction. J Clin Oncol 34:1448–1454. doi:10.1200/jco.2015.63.5995

Kang EJ, Im SA, Oh DY et al (2013) Irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin third-line chemotherapy after failure of fluoropyrimidine, platinum, and taxane in gastric cancer: treatment outcomes and a prognostic model to predict survival. Gastric Cancer 16:581–589. doi:10.1007/s10120-012-0227-5

Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Shimada K et al (2014) Biweekly irinotecan plus cisplatin versus irinotecan alone as second-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III trial (TCOG GI-0801/BIRIP trial). Eur J Cancer 50:1437–1445. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2014.01.020

Nishikawa K, Fujitani K, Inagaki H et al (2015) Randomised phase III trial of second-line irinotecan plus cisplatin versus irinotecan alone in patients with advanced gastric cancer refractory to S-1 monotherapy: TRICS trial. Eur J Cancer 51:808–816. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.02.009

Ohtsu A, Ajani JA, Bai YX et al (2013) Everolimus for previously treated advanced gastric cancer: results of the randomized, double-blind, phase III GRANITE-1 study. J Clin Oncol 31:3935–3943. doi:10.1200/jco.2012.48.3552

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for their participation in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kawakami, T., Machida, N., Yasui, H. et al. Efficacy and safety of irinotecan monotherapy as third-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 78, 809–814 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-016-3138-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-016-3138-z