Abstract

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have demonstrated high therapeutic efficacy in relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (r/r cHL). Nevertheless, despite the accumulated data, the question of the ICI therapy duration and efficacy of nivolumab retreatment remains unresolved. In this retrospective study, in a cohort of 23 adult patients with r/r cHL who discontinued nivolumab in complete response (CR), the possibility of durable remission achievement (2-year PFS was 55.1%) was demonstrated. Retreatment with nivolumab has demonstrated efficacy with high overall response rate (ORR) and CR (67% and 33.3% respectively). At the final analysis, all patients were alive with median PFS of 16.5 months. Grade 3–4 adverse events (AEs) were reported in 36% of patients, and there was no deterioration in terms of nivolumab retreatment–associated complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) have demonstrated high efficacy in the treatment of relapsed and refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (r/r cHL) in CHECKMATE-205 (nivolumab) and KEYNOTE-087 (pembrolizumab) studies [1, 2]. Introduction of immunotherapy to the treatment of cHL has transformed the concept of management and prognosis for this group of patients.

Nevertheless, despite the accumulated data, optimal duration of the ICI therapy is still unclear. In prior early studies, the nivolumab was discontinued in patients with r/r cHL predominantly due to either disease progression (25–28%) or severe treatment-related adverse events (5–11%) [1]. Published studies have demonstrated the possibility of durable remission achievement after ICI therapy discontinuation in patients with solid tumors [3,4,5,6,7,8]. At the same time, the analysis of CheckMate 153 performed by Spigel et al. (2017) demonstrated the significant improvement of PFS for patients with non-small cell lung cancer who continued therapy after 1 year compared to patients who stopped therapy after 1 year (PFS HR = 0.42 (95% CI, 0.25–0.71) [9]. However, in this study, patient groups were not well balanced according to achievement of complete or partial remission (70 vs 56%). The number of reports on therapy discontinuation in cHL patients is limited [10, 11]. The study by Manson et al. (2018) demonstrated that 91% of patients were alive at the last follow-up (median follow-up 21.2 months) and 80% of patients maintained CR after nivolumab discontinuation (total group was 11 patients) [10]. Therefore, there is evidence that a durable remission can be maintained after nivolumab discontinuation in patients with r/r cHL who achieved CR.

However, the results of previously published studies on ICI efficacy showed the absence of the PFS plateau in the survival curve for patients with r/r cHL. Most patients with Hodgkin lymphoma are not cured with PD-1-inhibitor therapy. Therefore, when deciding to discontinue ICI therapy, prognostic factors regarding the response duration should be defined and considered.

Assuming that such patients are refractory to conventional chemotherapy and the risk of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is high, ICI retreatment may be an attractive option in case of relapse after immunotherapy discontinuation. A limited number of previously published studies on ICI retreatment efficacy and safety in patients with solid tumors showed conflicting data [12,13,14,15]. Several reports were presented for patients with melanoma who had been retreated with ipilimumab monotherapy or in combination with nivolumab [16,17,18,19]. It was shown that ICI retreatment allowed to achieve favorable results for some of them. Noteworthy, for some patients the response to ICI retreatment was better compared to the initial therapy. Another study evaluating the response to ICI retreatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer demonstrated the achievement of partial remission or stable disease in 5 out of 11 patients [20]. Interestingly, patients who responded to primary therapy also had the good response to repeated therapy. In summary, the available published data does not clarify which patients can benefit from ICI re-challenge. Only a few clinical cases were published for patients with r/r cHL [10, 21]. In the study by Manson G. et al. (2018) devoted to the ICI discontinuation in patients with cHL, 4 patients were retreated with nivolumab after relapse. All patients achieved partial remission of the disease during nivolumab re-challenge [10]. Additionally, the results of pembrolizumab retreatment in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma were demonstrated in a 2-year follow-up of KEYNOTE-087 study [22]. The response was evaluated in 8 out of 10 patients. Overall response rate (ORR) was 75%. These findings suggest that ICI re-challenge may be a promising strategy in patients with r/r cHL.

Since this issue was not well understood yet, the aim of the current study was to assess the efficacy and safety of nivolumab retreatment in patients with r/r сHL. We suppose that patients who have previously achieved complete remission during primary nivolumab therapy may remain sensitive to ICI.

Methods

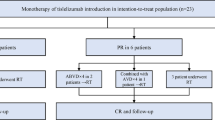

We retrospectively analyzed a cohort of 109 adult patients with r/r cHL receiving nivolumab (3 mg/kg every 14 days) in RM Gorbacheva Research Institute, Pavlov University, within Russian Named Patient Program. In 23 patients, the therapy was discontinued without any additional treatment after achieving complete remission. All these patients were included in our analysis. The disease status was assessed by positron-emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) using LYRIC criteria every 3 months.

Patients with r/r cHL who were at least 18 years old and relapsed after nivolumab discontinuation, were included in the retreatment efficacy and safety study. In all but one case, the nivolumab monotherapy was used; in one case ICI treatment was combined with chemotherapy. The dose of nivolumab was fixed at 40 mg or 3 mg/kg. The exclusion criteria were age under 18 years old and the history of another therapy between initial nivolumab and PD-1 inhibitor retreatment. The study was approved by Pavlov University Ethics Committee. All participants provided their written informed consent. The date of data cut-off was November 20, 2019.

The primary endpoint was ORR. Overall response rate was defined as rate of either complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) defined by LYRIC criteria. The secondary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Overall survival was defined as the time from nivolumab discontinuation to death from any cause. Progression-free survival 1 (PFS1) was defined as the time from nivolumab discontinuation to first documented progressive disease or death from any cause, whichever occurs first. Progression-free survival 2 (PFS2) was defined as the time from nivolumab retreatment to first documented progressive disease or death from any cause. In each survival outcome, data was censored at the date of last contact for patients who have not experienced the events of interest during their follow-up.

All patients receiving at least one therapy cycle were included in safety analysis. Adverse events (AEs) were evaluated according to NCI CTCAE 4.03 criteria.

For patients’ group characteristic evaluation, descriptive statistic methods were used. A full range of values was presented in descriptive statistics data where appropriate. The survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method. The univariate analysis of the influence of several factors on PFS after nivolumab discontinuation was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier method with log-rank test for nominal variables, and Cox regression for ordinal variables and continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics v.17 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Ill).

Results

The analysis included 23 adult patients with r/r cHL who discontinued nivolumab (3 mg/kg) in CR due to any reason. The PD-1 inhibitor therapy was discontinued due to Russian Named Patient Program completion in 20 (87%) patients or grade 3–4 AE in 3 (13%) patients. Adverse events included grade III colitis in 2 patients and combination of grade 3 arthritis and uveitis in 1 patient. Median follow-up after therapy discontinuation was 28.9 months (14.1–32.2) at the final analysis. There were 6 male and 17 female patients (26/74 %). Median age was 32 (20–48) years. Median number of lines of systemic therapy before nivolumab was 5 (3–10). In 11 (48%) cases prior therapy included autologous hemopoietic stem cell transplantation, also 11 (48%) patients had history of brentuximab vedotin treatment. At nivolumab therapy initiation, 6 (26%), 2 (9%), and 15 (65%) patients had stage II, III, and IV disease, respectively, with presence of B-symptoms in 14 (61%) cases and bulky disease (> 8 cm) in 1 (4%) case. Fourteen (61%) patients had progressive disease (PD), 4 (17%) stable disease (SD), and 3 (13%) partial response (PR) prior to nivolumab retreatment initiation. Performance status was evaluated by ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) score. Prior to initial ICI treatment, 10 (43%) patients had ECOG PS 0-1, 11 (48%) ECOG PS 2, and 2 (9%) ECOG PS 3 (Table 1). Median cycles of nivolumab were 24 (11-30). All patients achieved CR during the initial nivolumab therapy. Median number of nivolumab cycles before the best response achievement was 6 (6–24) with subsequent median nivolumab therapy duration of 7 (0–15) months (Table 2). At the moment of the last follow-up, all patients were alive (OS was 100%) (Fig. 1).

At the time of data cutoff, 11 (48%) patients with r/r cHL had relapsed after nivolumab therapy discontinuation. Median PFS1 was not reached: the 2-year PFS1 was 55.1% (95% CI, 32.3–73) (Fig. 2). Median time to relapse was 11 (5–26) months. All patients except one were retreated with nivolumab monotherapy. In 1 case nivolumab was combined with bendamustine and brentuximab vedotin at 1st cycle with 2 subsequent cycles of nivolumab combined with bendamustine followed by nivolumab monotherapy. At the time of the analysis, response was evaluated in 9 of 11 patients (Fig. 3). Median follow-up after ICI retreatment was 14.8 (2–25.4) months. With overall response rate of 67%, the best response was CR in 3 (33%), PR in 3 (33%), and indeterminate response (IR) in 3 (33%) patients (Fig. 4). Median number of nivolumab cycles to achieve the best response during nivolumab retreatment was 6 (6–12). Median time to achieve the best response was 3.6 (2.8–8.1) months. Retreatment was discontinued in 5 patients due to different reasons: grade 3–4 AE in 1 case and patient’s decision in 4 cases. At the moment of therapy discontinuation, 2 patients had CR, 1 patient PR, and 2 patients IR. Four out of five patients developed relapse after nivolumab retreatment was discontinued; in 1 case the disease progressed after 24 cycles of nivolumab retreatment. Median PFS2 was 16.5 months (95% CI, 16.3–16.7) (Fig. 1S). In patients relapsing after nivolumab retreatment, a different therapy was initiated consisting of nivolumab monotherapy (n = 3) or its combination with vinblastine (n = 1) or brentuximab vedotin and bendamustine (n = 1). None of these 5 patients was available for response evaluation at the time of the analysis. Close surveillance of these patients was continued.

In this study, the influence of several factors on PFS duration after nivolumab discontinuation was also examined. It was found that the early achievement of CR to nivolumab (3 months or 6 cycles) had a statistically significant effect on the duration of the remission after nivolumab discontinuation. At the last follow-up, 68.8% of patients who achieved CR at the moment of 3 months were alive and free of disease progression with median PFS not reached; median PFS for patients who achieved CR after 6 cycles of therapy was 13.3 months (p = 0.023; 95% CI, 5.8–20.8) (Fig. 4S). Other analyzed factors are presented in Table 1S in the Supplement Section. Potential predictors of response to nivolumab retreatment were also evaluated. None of the clinical characteristics assessed showed any predictive value (Table 2S).

During retreatment grade 3–4 AE occurred in 4 (36%) patients and included grade 3 arthralgia, grade 3 pyrexia, grade 3 thrombocytopenia, grade 4 pneumonitis, and pneumonia. At the same time, during the initial nivolumab therapy, grade 3–4 AEs were present in 5 out of 11 patients (45%). Interestingly, 1 out of 4 patients with grade 3–4 AE had no complications during initial nivolumab therapy. Grade ≤ 2 AEs were present in 2 patients: grade 1 creatinine elevation and grade 2 leukopenia. Only in one case of grade 3–4 AE (pneumonitis), the therapy was stopped and glucocorticoids therapy at 1 mg/kg was initiated, while the patient achieved CR before therapy discontinuation. There was no deterioration in terms of complications during retreatment with nivolumab. In addition, not all patients experienced relapse of the same complications that were present during primary therapy.

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are the effective treatment modality for patients with r/r cHL [1, 2, 23, 24]. However, the question of the ICI therapy duration has not been defined yet. Discontinuation of immune checkpoint inhibitors is a highly relevant issue. The key factors to be considered in this regard are as follows: development of adverse events in most patients, need for a regular long-term treatment, which has effect on the quality of life, and financial toxicity of such treatment. According to the published studies, the main reasons for therapy discontinuation were disease progression and severe adverse events. In our group of patients who achieved CR at the time of therapy cessation, in most cases the therapy was stopped due to the Named Patient Program closure and in 3 patients (13%)—due to grade 3–4 AEs. The previously published data demonstrated the possibility of durable remission achievement after PD-1 inhibitor discontinuation in patients with solid tumors [3,4,5,6,7,8,9] and Hodgkin lymphoma [10, 11]. In the current study, we also observed the long-term remission after nivolumab discontinuation in patients with r/r cHL. With median follow-up of 26 months, median PFS was not reached. Therefore, therapy discontinuation is a feasible option for some patients.

Nevertheless, defining prognostic factor for durable remission after nivolumab discontinuation is still an important task. In our study, the only factor with statistically significant influence on PFS probability defined by Kaplan–Meier method was early (at 3 months or 6 therapy cycles) response to nivolumab (Fig. 4S). However, this result should be considered with caution due to limited number of patients in analyzed population.

At the same time, the published reports demonstrated that patients with r/r cHL continue to relapse after ICI therapy [1, 2, 23]. The similar outcome was observed in our cohort of patients discontinuing nivolumab in CR as 48% of them developed a relapse in 2 years past therapy cessation. Thus, the solution to question of ICI therapy discontinuation in r/r cHL is closely related to the problem of choice of the next therapy step. Considering the refractory course of the disease, and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) associated risks, ICI retreatment seems to be a reliable option for patients who have achieved CR during the previous treatment. Although the currently published data is limited to case reports, it also seems to confirm this concept [10, 21].

Our study is the first detailed description which reports the outcome of nivolumab retreatment in patients with r/r cHL. We received encouraging data demonstrating that the ICI re-challenge may be safe and effective in patients who achieved CR during the initial nivolumab therapy. Limitations of this report include a retrospective study design within a single institution, which may lead to the selection bias, limited number of patients, and lack of comparator arm.

The minimum dose of nivolumab used in our study was 40 mg disregard of bodyweight. The efficacy and safety of nivolumab 40 mg fixed dose in patients with r/r cHL were assessed by our group in prospective setting, demonstrating that response rate and duration after 40 mg nivolumab treatment were comparable to standard 3 mg/kg dosing regimen [25].

The LYRIC criteria were used to avoid early discontinuation of immunotherapy in patients for which it could be potentially beneficial despite unconventional response pattern. These criteria were implemented prospectively on a large population of patients during Russian national nivolumab named patient program with results published by our group earlier [23], showing ORR and response duration comparable to conventional criteria data presented by other groups. All patients who achieved IR as the best response to nivolumab retreatment in this study (3/9 pts) had no signs of active disease during the entire treatment. These patients were not counted as having an objective response. Therefore, this reconsideration of response criteria would not affect the overall response rate and main results of the study (Figure 2S, 3S).

The overall response rate of 67% was comparable with previously published data of phase 2 KEYNOTE-087 study, demonstrating the 75% ORR after pembrolizumab retreatment [22]. In addition, other single case reports also demonstrated the achievement of complete and partial response to nivolumab retreatment [10, 21]. However, despite the inspiring results, relapses after nivolumab discontinuation, as well as after nivolumab retreatment, demonstrate that most patients are not cured with PD-1 inhibitors monotherapy, pointing to the need for response consolidation. In patients with inadequate response or relapse after nivolumab retreatment, allo-HSCT should be considered when possible. While allo-HSCT has proven its curative potential, this method poses a substantial risk of severe complications. At the same time, nivolumab retreatment in sensitive to PD-1 therapy patients allows to achieve significant overall survival with a good quality of life. In addition, several clinical trials are currently ongoing to assess the potential of new molecules and combinations that may prove to be effective in the treatment of r/r cHL in the near future [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34].

Summary

In conclusion, the study shows that ICI discontinuation is a feasible option for some patient groups. Also, data was obtained suggesting that the ICI re-challenge is an effective and safe approach. Although the results are encouraging, further study of nivolumab discontinuation and retreatment, as well as predictor factors of response and survival in a larger population of patients, is necessary.

Data Availability

Not applicable

References

Armand P, Engert A, Younes A, Fanale M, Santoro A, Zinzani PL, Timmerman JM, Collins GP, Ramchandren R, Cohen JB, de Boer JP, Kuruvilla J, Savage KJ, Trneny M, Shipp MA, Kato K, Sumbul A, Farsaci B, Ansell SM (2018) Nivolumab for relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma after failure of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation: extended follow-up of the multicohort single-arm phase II CheckMate 205 trial. J Clin Oncol 36(14):1428–1439. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.76.0793

Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, Armand P, Johnson NA, Brice P, Radford J, Ribrag V, Molin D, Vassilakopoulos TP, Tomita A, von Tresckow B, Shipp MA, Zhang Y, Ricart AD, Balakumaran A, Moskowitz CH, for the KEYNOTE-087 (2017) KEYNOTE-087. Phase II study of the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 35(19):2125–2132. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1316

Gauci M, Lanoy E, Champiat S, Caramella C et al (2019) Long-term survival in patients responding to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and disease outcome upon treatment discontinuation. Clinical Cancer Research 25(3):946–956. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-18-0793

Tachihara M, Negoro S, Inoue T, Tamiya M, Akazawa Y, Uenami T, Urata Y, Hattori Y, Hata A, Katakami N, Yokota S (2018) Efficacy of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies after discontinuation due to adverse events in non-small cell lung cancer patients (HANSHIN 0316). BMC Cancer 18:946. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-018-4819-2

Jansen YJL, Rozeman EA, Mason R, Goldinger SM, Geukes Foppen MH, Hoejberg L, Schmidt H, van Thienen JV, Haanen JBAG, Tiainen L, Svane IM, Mäkelä S, Seremet T, Arance A, Dummer R, Bastholt L, Nyakas M, Straume O, Menzies AM, Long GV, Atkinson V, Blank CU, Neyns B (2019) Discontinuation of anti-PD-antibody therapy in the absence of disease progression or treatment limiting toxicity: clinical outcomes in advanced melanoma. Annals of Oncology 30(7):1154–1161. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz110

Myint ZW, Arays R, Raajasekar AKA, Wang P (2018) Long-term outcomes in patients after discontinuation of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Res Med 1(3):1–4. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e15086

Atkinson VG, Ladwa R (2016) Complete responders to anti-PD1 antibodies. What happens when we stop? Ann Oncol 27(6):1116P. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw379.11

Myint Z, Arays R, Raajasekar AKA, Huang B, Chen Q, Wang P (2018) Long-term outcomes in patients after discontinuation of PD1/PDL1 inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 36:e15086. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e15086

Spigel DR, et al (2017) CHECKMATE153: Randomized results of continuous vs 1-year fixed-duration nivolumab in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 28:5. Abstract 1297O. https://www.primeoncology.org/app/uploads/prime_activities/42584/VPS_Madrid_1297O_Lung_Spigel.pdf

Manson G, Herbaux C, Brice P, Bouabdallah K, Stamatoullas A, Schiano JM, Ghesquieres H, Dercle L, Houot R, Lymphoma Study Association (2018) Prolonged remissions after anti-PD-1 discontinuation in patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 131:2856–2859. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-03-841262

Lepik K, Fedorova L, Mikhailova N et al (2019) Cessation of immune checkpoint inhibitors therapy in r/r Hodgkin lymphoma: should we consider HSCT? 45th Annual Meeting of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, Abstract collection. Poster number A232

Goodman A (2017) Retreatment with checkpoint inhibitors may be feasible for some patients with NSCLC. The ASCO post. https://www.ascopost.com/issues/july-10-2017/retreatment-with-checkpoint-inhibitors-may-be-feasible-for-some-patients-with-nsclc. Accessed 10 June 2017

Santini FC, Rizvi H, Wilkins O, van Voorthuysen M, Panora E, Halpenny D, Kris MG, Rudin CM, Chaft JE, Hellmann MD (2017) Safety of retreatment with immunotherapy after immune-related toxicity in patients with lung cancers treated with anti-PD(L)-1 therapy. J Clin Oncol 35(15):9012. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9012

Fujita K, Uchida N, Yamamoto Y, et al (2019) Retreatment with anti-PD-L1 antibody in advanced non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with anti-PD-1 antibodies. Anticancer Research 39(7):3917–3921. 10.21873/anticanres.13543

Alaiwi SA, Martini DJ, Xie W et al (2019) Safety and efficacy of restarting immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) after immune-related adverse events (irAEs) in metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC). J Clin Oncol 37(7):652–652. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2019.37.7_suppl.652

Pollack MH, Betof A, Dearden H, Rapazzo K, Valentine I, Brohl AS, Ancell KK, Long GV, Menzies AM, Eroglu Z, Johnson DB, Shoushtari AN (2018) Safety of resuming anti-PD-1 in patients with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) during combined anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD1 in metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 29:250–255. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx642

Lebbé C, Weber JS, Maio M, Neyns B, Harmankaya K, Hamid O, O'Day SJ, Konto C, Cykowski L, McHenry MB, Wolchok JD (2014) Survival follow-up and ipilimumab retreatment of patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab in prior phase II studies. Ann Oncol 25:2277–2284. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu441

Chiarion-Sileni V, Pigozzo J, Ascierto PA, Simeone E, Maio M, Calabrò L, Marchetti P, de Galitiis F, Testori A, Ferrucci PF, Queirolo P, Spagnolo F, Quaglino P, Carnevale Schianca F, Mandalà M, di Guardo L, del Vecchio M (2014) Ipilimumab retreatment in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: the expanded access programme in Italy. Br J Cancer 110:1721–1726. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.126

Robert C, Schadendorf D, Messina M, Hodi FS, O'Day S, MDX010-20 investigators (2013) Efficacy and safety of retreatment with ipilimumab in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma who progressed after initially achieving disease control. Clin Cancer Res 19:2232–2239. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3080

Maiko N, Nakaya A, Kurata T, et al (2018) Immune checkpoint inhibitor re-challenge in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 9(64):32298–32304. 10.18632/oncotarget.25949

Pellegrini C, Casadei B, Cellini C, Argnani L, Cavo M, Zinzani PL (2018) Sequential double bridging to transplant with diversified anti-PD1 monoclonal antibodies retreatment in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: a case report. J Cancer Sci Ther 10(6):149. https://doi.org/10.4172/1948-5956.1000534

Chen R, Zinzani PL, Lee HJ, Armand P, Johnson NA, Brice P, Radford J, Ribrag V, Molin D, Vassilakopoulos TP, Tomita A, von Tresckow B, Shipp MA, Lin J, Kim E, Nahar A, Balakumaran A, Moskowitz CH (2019) Pembrolizumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma: two-year follow-up of KEYNOTE-087. Blood. 134:1144–1153. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2019000324

Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB, Moiseev IS, et al (2019) Nivolumab for the treatment of relapsed and refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma after ASCT and in ASCTnaïve patients. Leukemia & Lymphoma 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2019.1573368

Kozlov AV, Kazantzev IV, Iukhta TV, et al (2019) Nivolumab in pediatric Hodgkin’s lymphoma. CTT. 10.18620/ctt-1866-8836-2019-8-4-41-48

Lepik KV, Fedorova LV, Kondakova EV et al (2020) A phase 2 study of nivolumab using a fixed dose of 40 mg (Nivo40) in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Hemasphere 4(5):480. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000480

Shi Y, Su H, Song Y, Jiang W, Sun X, Qian W, Zhang W, Gao Y, Jin Z, Zhou J, Jin C, Zou L, Qiu L, Li W, Yang J, Hou M, Zeng S, Zhang Q, Hu J, Zhou H, Xiong Y, Liu P (2019) Safety and activity of sintilimab in patients with relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (Orient-1): a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 6:e12–e19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30192-3

Song Y, Gao Q, Zhang H, Fan L, Zhou J, Zou D, Li W, Yang H, Liu T, Wang Q, Lv F, Yang Y, Guo H, Yang L, Elstrom R, Huang J, Novotny W, Wei V, Zhu J (2018) Tislelizumab (Bgb-A317) for relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma: preliminary efficacy and safety results from a phase 2 study. Blood 132:682. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-99-117848

Nie J, Wang C, Liu Y, Yang Q, Mei Q, Dong L, Li X, Liu J, Ku W, Zhang Y, Chen M, An X, Shi L, Brock MV, Bai J, Han W (2019) Addition of low-dose decitabine to anti-Pd-1 antibody camrelizumab in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 37:1479–1489. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.02151

Chen R, Gibb AL, Collins GP, Popat R, el-Sharkawi D, Burton C, Lewis D, Miall FM, Forgie A, Compagnoni A, Andreola G, Brar S, Thall A, Woolfson A, Radford J (2017) Blockade of the PD-1 checkpoint with anti–PD-L1 antibody Avelumab is sufficient for clinical activity in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL). Hematol Oncol 35:67. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2437_54

Hamadani M, Collins GP, Samaniego F, Spira AI, Davies A, Radford J, Caimi P, Menne T, Boni J, Cruz H, Feingold J, He S, Wuerthner J, Horwitz SM (2018) Phase 1 study of Adct-301 (Camidanlumab Tesirine), a novel pyrrolobenzodiazepine-based antibody drug conjugate, in relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 132:928. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2018-99-118198

Rothe A, Sasse S, Topp MS, Eichenauer DA, Hummel H, Reiners KS, Dietlein M, Kuhnert G, Kessler J, Buerkle C, Ravic M, Knackmuss S, Marschner JP, Pogge von Strandmann E, Borchmann P, Engert A (2015) A phase 1 study of the bispecific anti-CD30/CD16A antibody construct Afm13 in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 125:4024–4031. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-12-614636

Smith SM, Schöder H, Johnson JL, et al (2013) The Anti-CD80 primatized monoclonal antibody, galiximab, is well-tolerated but has limited activity in relapsed Hodgkin lymphoma: cancer and leukemia group B 50602 (Alliance) Leukemia & Lymphoma 54:1405–1410. 10.3109/10428194.2012.744453

Freedman AS, Kuruvilla J, Assouline SE et al (2010) Clinical activity of lucatumumab (Hcd122) in patients (Pts) with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin or non-Hodgkin lymphoma treated in a phase Ia/II clinical trial (NCT00670592). Blood 116:284. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V116.21.284.284

Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB, Kondakova EV, Zalyalov YR, Fedorova LV, Tsvetkova LA, Kotselyabina PV, Borzenkova ES, Babenko EV, Popova MO, Darskaya EI, Baykov VV, Moiseev IS, Afanasyev BV (2020) A study of safety and efficacy of nivolumab and bendamustine (NB) in patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma after nivolumab monotherapy failure. HemaSphere 4:e401. https://doi.org/10.1097/HS9.0000000000000401

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Alexander Kulagin, Ilya Kazantzev, and Vladislav Evseev for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: Fedorova LV, Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB, Moiseev IS, Afanasyev BV

Provision of study materials or patients: Fedorova LV, Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB, Kondakova EV, Zalyalov YR, Kozlov AV, Babenko EV, Baykov VV

Collection and assembly of data: Fedorova LV, Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB, Kondakova EV, Zalyalov YR, Kozlov AV

Data analysis and interpretation: Fedorova LV, Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB, Kondakova EV, Moiseev IS, Afanasyev BV.

Manuscript writing: Fedorova LV, Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB

Final approval of manuscript: all authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: Fedorova LV, Lepik KV, Mikhailova NB

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and approved by the institutional review board. All enrolled patients gave written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Code availability

Not applicable

Materials availability

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedorova, L.V., Lepik, K.V., Mikhailova, N.B. et al. Nivolumab discontinuation and retreatment in patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Hematol 100, 691–698 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-021-04429-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-021-04429-8