Abstract

The role of autologous stem cell transplantation (autoSCT) as consolidating treatment for peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL) is unsettled. The aim of this analysis was to investigate the impact of autoSCT in the upfront setting by intent-to-treat and to study salvage strategies after relapse. Retrospective follow-up of all patients aged 18–70 years and treated at our institution for ALK-PTCL diagnosed between 2001 and 2014. Of 117 eligible patients, diagnosis was PTCL-NOS in 34, ALCL ALK− in 31, AITL in 28, and other PTCL in 24 patients. Disregarding 20 patients who received first-line treatment externally, upfront autoSCT was not intended in 34 due to comorbidity, higher age, low IPI, physician’s decision or unknown reasons (nITT), while intent-to-transplant (ITT) was documented in 63 patients. ITT was not associated with significant benefits for 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) with 46 and 23% in the ITT group vs. 42 and 25% in the nITT group, even after multivariate adjustment for confounders. Altogether, 91 of all 117 patients relapsed or progressed. Thirty-one patients managed to proceed to salvage allografting and achieved a 5-year OS of 52%. In contrast, all 7 patients receiving salvage autoSCT relapsed and died, and only 3 of the 51 patients not eligible for SCT salvage survived. In this study, a significant benefit of intending first-line autoSCT over non-transplant induction in patients with ALK-PTCL did not emerge. Most patients fail first-line treatment and have a poor outlook if salvage alloSCT cannot be performed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peripheral T-cell lymphomas (PTCLs) are a rare and heterogeneous group of generally aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHLs) [1]. In comparison to aggressive B-cell lymphomas, the prognosis of PTCL is poor, except for anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive ALCL (ALCL ALK+) [1]. With standard CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) or CHOEP (CHOP plus etoposide)-based first-line therapy, the 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) ranged from 21 to 61% in patients with PTCL not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS), anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative ALCL (ALCL ALK−), and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL), depending on the patient’s IPI (International Prognostic Index) [2,3,4]. More intensive chemotherapy regimens do not appear to improve the prognosis of patients with PTCL [5, 6]. Moreover, consolidation of first-line responses with autologous stem cell transplantation (autoSCT) has been evaluated in PTCL [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, in the absence of comparative trials, the role of autoSCT for early consolidation in PTCL remains unclear [2].

In case of relapse, the outcome has been found to be extremely dismal with median survival times of only a few months in unselected population-based studies [7, 16, 17]. In contrast, most studies restricted to patients selected for transplantation actually performed reported a substantial proportion of long-term survivors both after autoSCT and allogeneic stem cell transplantation (alloSCT) [10, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the feasibility and efficacy of autoSCT in the upfront setting and the impact of stem cell transplantation on the outcome of relapsed or refractory PTCL in an unselected population.

Patients and methods

Study design and patient eligibility

Eligible for this retrospective single-center analysis were all consecutive patients aged 18–70 years who were referred to the University of Heidelberg for treatment of PTCL between 2001 and 2014. All diagnoses were made or confirmed by an experienced hematopathologist. ALCL ALK+ and primary cutaneous lymphomas except ALCL ALK− with systemic manifestations were excluded as well as T-cell leukemias. The primary objective of the first part of the study was to analyze the impact of an intent-to-autoSCT strategy in first-line treatment on outcome. The primary objective of the second part of the study was to investigate the impact of autologous and allogeneic transplantation on survival after PTCL relapse.

All patients gave written informed consent to data collection and scientific evaluation. Data analysis was approved by the Institutional Review Board (Approval S-200/2010).

Definitions

Disease response was defined according to the response criteria for lymphomas [26]. If the intention to autoSCT or alloSCT for consolidation after first-line treatment was documented and/or a stem cell mobilization attempt planned and/or a donor search initiated, patients were assigned to the intent-to-transplant group (ITT), whereas all other patients were considered as not intended to be transplanted (nITT).

Statistical analysis

Co-primary endpoints for the first part of the study were PFS and overall survival (OS) calculated from start of therapy. Primary endpoint of the second part of the study was OS from first relapse. PFS-defining events were relapse/disease progression or death from any cause. The OS-defining event was death from any cause. Survival times were calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Median survival and p values are presented. The median follow-up (FU) was calculated by reversed Kaplan-Meier estimate. Categorical variables were described by absolute and relative frequencies. Quantitative variables were summarized by median and interquartile range. The Fisher’s exact test was used for testing associations between qualitative variables, Mann-Whitney test was used to compare quantitative variables between two groups, respectively. Statistical analyses were done with GraphPad Prism (release 5.0; San Diego, CA, USA); multivariate analysis for OS and PFS was made by Cox regression using IBM SPPS Statistics (release 24.0; Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Patients

Overall, 119 patients met the inclusion criteria. Two of them with a very aggressive course were diagnosed only after death and excluded from further analysis. In 20 patients, first-line treatment had been performed externally. Nineteen of these were referred to us with refractory disease or relapse; 2 of them after first-line autoSCT. The remaining patient was referred in complete remission (CR) after autoSCT performed externally. The other 97 patients were referred before or during first-line treatment without a preceding relapse or refractory disease (Fig. 1).

Patient characteristics and outcome by intent-to-transplantation

Disregarding the 20 patients who had received first-line treatment externally, autoSCT in first remission was intended in 63 patients (ITT), while 34 patients were not intended to be transplanted because of comorbidity, higher age, low IPI, physician’s decision, or unknown reasons (nITT). Also, three patients who died within 2 weeks after starting therapy were assigned to the nITT group.

In the nITT group, median age was slightly higher, but a significantly smaller proportion of patients had an elevated LDH (although not translating into a significant IPI difference), and a significantly higher fraction of patients received induction other than CHOP/CHOEP. Detailed patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

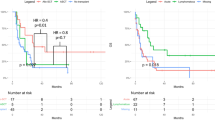

Both 5-year OS and PFS were not statistically different with 46 and 23% in the ITT group vs. 42 and 25% in the nITT group, respectively (Fig. 2).

By multivariate analysis adjusting for gender, age, IPI, PTCL subtype, and ITT, only younger age was associated with significant benefits for OS but not for PFS (Table 2).

Autologous transplantation in first remission

In the ITT group, transplantation was actually performed in 34 patients (54%). Thirty-two patients underwent autoSCT and 2 an allograft. Disease status at SCT was chemorefractory in two patients (one each in the autoSCT and alloSCT group), whereas all other patients proceeding to SCT had chemosensitive disease. Reasons for not undergoing transplantation though intended are detailed in Fig. 1.

Altogether, 72 of the 117 patients (62%) achieved at least partial remission (PR) after induction therapy. Thirty-four (47%) of them received an autoSCT for consolidation, while 38 patients (53%) with a response duration of at least 2 months did not because transplant was not intended or not possible due to the reasons listed in Fig. 1. Consolidation with autologous transplantation in first remission was not associated with a significant benefit compared to non-transplanted patients (5-year PFS 35 vs 27%, p = 0.96; 5-year OS 58 vs 47%, p = 0.39).

Relapse and outcome by secondary treatment strategies

Altogether, 91 of the 117 eligible patients (78%) were primary refractory (n = 47, 40%) or relapsed within (n = 19, 16%) or beyond 6 months after end of first-line therapy (n = 25, 21%). Two patients died within 2 weeks after starting first-line therapy due to a very aggressive course of disease and were therefore excluded from further analysis regarding relapse management (Fig. 3).

Primary relapse treatment policy in eligible patients was attempting alloSCT after re-induction with salvage chemotherapy. Patients not eligible for alloSCT who had not undergone autoSCT as part of first-line therapy were considered for salvage autoSCT. DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin) was the most frequently used chemotherapy for re-induction (n = 39), followed by high-dose methotrexate (n = 7) and DexaBEAM (dexamethasone, carmustine, etoposide, cytarabine, melphalan; n = 4). Seven patients received other poly-chemotherapy protocols, 16 patients obtained mono-chemotherapy, 2 underwent a radiation for local disease control, and 9 patients got steroid monotherapy only. Brentuximab was used for first salvage therapy in 4 and for subsequent-line therapy in 6 further patients.

Median second PFS and OS after relapse/progression was only 3 and 7 months, respectively, resulting in a 5-year OS of 20% (95% confidence interval (95%CI) 12–30%). Time of relapse after induction therapy did not predict the post-relapse outcome (Fig. 4).

Overall, 51 patients (57%) could not proceed to SCT generally because of progressive disease (38%), poor performance status (43%), or advanced age (8%). Of these, only three patients were alive at the time of data cut-off, two of them with a very short follow-up, translating into a median OS after relapse of 3 months. Of the 38 patients who managed to proceed to SCT, 31 underwent an alloSCT, 7 of them (23%) with chemorefractory disease (Table 3).

While 14 allografted patients died of progressive disease (n = 7) or non-relapse mortality (NRM; n = 7), 17 patients live disease-free at a median follow-up of 5.8 years (1.4–12.3) after relapse, corresponding to an estimated 5-year OS of 52% (95%CI 32–68%) (Fig. 5). In contrast, all seven patients who received an autoSCT as only salvage transplant strategy died of progressive disease, with a median OS of 10 months (Fig. 3). Relapsed patients from the ITT group underwent an alloSCT (43%) more frequently than patients in the nITT group (20%).

Moreover, only younger age, but neither time to relapse nor PTCL subset or IPI had a significant impact on survival after relapse by multivariate analysis (Table 2).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the natural course of ALK− PTCL in an unselected population with particular focus on transplant strategies in the first-line and salvage settings. In patients scheduled for upfront autoSCT, transplantation was feasible only in 54% of the patients. The most frequent reason for failure was primary refractory disease. On intent-to-treat analysis, the estimated 5-year PFS was less than 25% irrespective of intent-to-transplant. These results appear to be worse than those of the prospective trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL), where a 3-year PFS of 41 to 50% in patients with PTCL-NOS, ALCL ALK−, and AITL could be obtained [3]. Selection bias in the prospective trials may contribute to this difference. In population-based studies, 5-year PFS was about 20–30% [1, 7, 27] and therefore comparable to our study.

The impact of upfront autoSCT has been investigated in a few prospective and some retrospective studies [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In the largest prospective series, a phase II trial of the Nordic Lymphoma Group, 160 patients with untreated PTCL except ALCL ALK+ were intended to undergo autoSCT after standard CHOP-based induction. Early failures occurred in 26%, but 72% of patients underwent transplantation leading to a 5-year PFS of 44% [9]. Similar results have been reported in a German intent-to-transplant trial on 111 patients [8]. In these two prospective studies, however, only patients who were considered to tolerate autoSCT were included. Selection bias might be even stronger in retrospective studies on upfront autoSCT selecting for patients actually transplanted [6, 10, 11, 14], where 5-year PFS rates of up to 80% have been reported [10].

Similarly, a 5-year PFS of 41% was observed in the ITT group of a large population-based retrospective study from Sweden [7], with 68% of 128 patients planned for upfront autoSCT actually receiving a transplant. This was significantly better than the 5-year PFS of 20% in 124 comparable patients who were not planned to be transplanted. One caveat raised by the investigators of the Swedish study was a possible selection bias caused by early treatment failures who may not been included in the ITT-autoSCT group. In keeping with this hypothesis, the overall response rate (ORR) to first-line treatment was lower in the present study with only 62%, partly explaining why the proportion of patients proceeding to a planned autoSCT was smaller (54%), and contributing to the comparably poor 5-year PFS of only 23%.

However, even when restricting the analysis to those 72 patients who actually responded to induction, we were not able to show a significant benefit of a consolidative autoSCT. This finding is in line with two recent retrospective studies including only patients with PTCL in first remission who underwent or did not undergo autoSCT consolidation [28, 29].

In case of relapse, alloSCT appears to be the most potent tool for achieving durable disease control [30]. In our study, sustained remissions and long-term survival were only observed after allogeneic transplantation, even though 23% of the patients underwent alloSCT in a chemorefractory disease status. NRM and death due to progression were each 23%, which is similar to results reported previously [18,19,20,21]. Patients intended to upfront autoSCT underwent more often an alloSCT in case of relapse than those not scheduled for initial transplantation, which may have contributed to the trend for better OS in patients intended to transplant first line. In contrast, none of the patients who were unable to proceed to alloSCT in case of relapse enjoyed durable disease control, if any. Notably, this included patients who underwent salvage autoSCT. This is in contradiction to a variety of registry studies which suggest 3-year PFS rates of up to 42% in patients undergoing autoSCT in chemosensitive relapse [10, 11, 25, 31]. However, the number of patients receiving autoSCT was small in our study, and the non-alloSCT group represents a negative selection by including all patients who were too progressive, too sick, or for other reasons ineligible for alloSCT.

The results of alloSCT observed in the present study are comparable to recent findings by Chihara et al. who investigated the outcome of 321 patients with PTCL-NOS or AITL failing first-line therapy. In their analysis, 5-year OS of the 31 patients who proceeded to alloSCT was 52%. Although in that study the proportion of patients actually receiving alloSCT was < 10% and thus much smaller than in the present study (35%), the global OS was similar with 24% at 5 years [32]. The reason for this is that the 5-year OS of patients treated with autoSCT only (n = 36,) and of patients never transplanted was better than in the present study with 32 and 10%, respectively. Nevertheless, the results of our study strongly suggest that early alloSCT should be attempted in patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL if ever possible, especially given the fact that at every line of relapse/progression a large fraction of patients with PTCL will be unable to undergo any further treatment [7, 16, 17, 32].

With the recent advent of novel therapeutic options, such as brentuximab vedotin and checkpoint inhibitors, the outlook in particular of relapsed ALCL may dramatically improve [33, 34]. However, these agents were unavailable for the patients analyzed here except for brentuximab in a few patients with ALCL treated from 2012 onwards.

Interestingly, our data showed that time of relapse after induction therapy does not appear to predict the post-relapse outcome. This is in contrast to experience in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma who have a worse outcome if relapse occurred within 12 months after diagnosis [35], just as in patients with mantle cell lymphoma [36] and follicular lymphoma [37] relapsing within 1 year after upfront autoSCT.

In conclusion, a significant benefit of intending first-line autoSCT over non-transplant induction in patients with ALK− PTCL did not emerge in this study. More than three quarters of all patients will fail first-line treatment irrespective of autoSCT intention. These patients have a very poor outlook regardless of duration of first remission if salvage alloSCT cannot be performed, giving a rationale for using this modality early in patients with PTCL relapse.

References

Vose J, Armitage J, Weisenburger D (2008) International peripheral T-cell and natural killer/T-cell lymphoma study: pathology findings and clinical outcomes. J Clin Oncol 26:4124–4130. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.16.4558

Moskowitz AJ, Lunning MA, Horwitz SM (2014) How I treat the peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Blood 123:2636–2644. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-12-516245

Schmitz N, Trumper L, Ziepert M, Nickelsen M, Ho AD, Metzner B, Peter N, Loeffler M, Rosenwald A, Pfreundschuh M (2010) Treatment and prognosis of mature T-cell and NK-cell lymphoma: an analysis of patients with T-cell lymphoma treated in studies of the German high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma study group. Blood 116:3418–3425. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2010-02-270785

Sonnen R, Schmidt WP, Muller-Hermelink HK, Schmitz N (2005) The international prognostic index determines the outcome of patients with nodal mature T-cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol 129:366–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05478.x

Escalon MP, Liu NS, Yang Y, Hess M, Walker PL, Smith TL, Dang NH (2005) Prognostic factors and treatment of patients with T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer 103:2091–2098. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.20999

Nickelsen M, Ziepert M, Zeynalova S, Glass B, Metzner B, Leithaeuser M, Mueller-Hermelink HK, Pfreundschuh M, Schmitz N (2009) High-dose CHOP plus etoposide (MegaCHOEP) in T-cell lymphoma: a comparative analysis of patients treated within trials of the German high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma study group (DSHNHL). Ann Oncol 20:1977–1984. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp211

Ellin F, Landstrom J, Jerkeman M, Relander T (2014) Real-world data on prognostic factors and treatment in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a study from the Swedish Lymphoma Registry. Blood 124:1570–1577. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-04-573089

Wilhelm M, Smetak M, Reimer P, Geissinger E, Ruediger T, Metzner B, Schmitz N, Engert A, Schaefer-Eckart K, Birkmann J (2016) First-line therapy of peripheral T-cell lymphoma: extension and long-term follow-up of a study investigating the role of autologous stem cell transplantation. Blood Cancer J 6:e452. https://doi.org/10.1038/bcj.2016.63

d'Amore F, Relander T, Lauritzsen GF, Jantunen E, Hagberg H, Anderson H, Holte H, Osterborg A, Merup M, Brown P, Kuittinen O, Erlanson M, Ostenstad B, Fagerli UM, Gadeberg OV, Sundstrom C, Delabie J, Ralfkiaer E, Vornanen M, Toldbod HE (2012) Up-front autologous stem-cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: NLG-T-01. J Clin Oncol 30:3093–3099. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2011.40.2719

Smith SM, Burns LJ, van Besien K, Lerademacher J, He W, Fenske TS, Suzuki R, Hsu JW, Schouten HC, Hale GA, Holmberg LA, Sureda A, Freytes CO, Maziarz RT, Inwards DJ, Gale RP, Gross TG, Cairo MS, Costa LJ, Lazarus HM, Wiernik PH, Maharaj D, Laport GG, Montoto S, Hari PN (2013) Hematopoietic cell transplantation for systemic mature T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 31:3100–3109. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.46.0188

Rodriguez J, Caballero MD, Gutierrez A, Marin J, Lahuerta JJ, Sureda A, Carreras E, Leon A, Arranz R, Fernandez de Sevilla A, Zuazu J, Garcia-Larana J, Rifon J, Varela R, Gandarillas M, SanMiguel J, Conde E (2003) High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma: the GEL-TAMO experience. Ann Oncol 14:1768–1775

Rodriguez J, Conde E, Gutierrez A, Arranz R, Leon A, Marin J, Bendandi M, Albo C, Caballero MD (2007) Frontline autologous stem cell transplantation in high-risk peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a prospective study from The Gel-Tamo Study Group. Eur J Haematol 79:32–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.00856.x

Reimer P, Rudiger T, Geissinger E, Weissinger F, Nerl C, Schmitz N, Engert A, Einsele H, Muller-Hermelink HK, Wilhelm M (2009) Autologous stem-cell transplantation as first-line therapy in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 27:106–113. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.17.4870

Corradini P, Tarella C, Zallio F, Dodero A, Zanni M, Valagussa P, Gianni AM, Rambaldi A, Barbui T, Cortelazzo S (2006) Long-term follow-up of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas treated up-front with high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation. Leukemia 20:1533–1538. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.leu.2404306

Mercadal S, Briones J, Xicoy B, Pedro C, Escoda L, Estany C, Camos M, Colomo L, Espinosa I, Martinez S, Ribera JM, Martino R, Gutierrez-Garcia G, Montserrat E, Lopez-Guillermo A (2008) Intensive chemotherapy (high-dose CHOP/ESHAP regimen) followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation in previously untreated patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol 19:958–963. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn022

Mak V, Hamm J, Chhanabhai M, Shenkier T, Klasa R, Sehn LH, Villa D, Gascoyne RD, Connors JM, Savage KJ (2013) Survival of patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma after first relapse or progression: spectrum of disease and rare long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol 31:1970–1976. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.44.7524

Biasoli I, Cesaretti M, Bellei M, Maiorana A, Bonacorsi G, Quaresima M, Salati M, Federico M, Luminari S (2015) Dismal outcome of T-cell lymphoma patients failing first-line treatment: results of a population-based study from the Modena Cancer Registry. Hematol Oncol 33:147–151. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2144

Corradini P, Dodero A, Zallio F, Caracciolo D, Casini M, Bregni M, Narni F, Patriarca F, Boccadoro M, Benedetti F, Rambaldi A, Gianni AM, Tarella C (2004) Graft-versus-lymphoma effect in relapsed peripheral T-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas after reduced-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic transplantation of hematopoietic cells. J Clin Oncol 22:2172–2176. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2004.12.050

Dodero A, Spina F, Narni F, Patriarca F, Cavattoni I, Benedetti F, Ciceri F, Baronciani D, Scime R, Pogliani E, Rambaldi A, Bonifazi F, Dalto S, Bruno B, Corradini P (2012) Allogeneic transplantation following a reduced-intensity conditioning regimen in relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphomas: long-term remissions and response to donor lymphocyte infusions support the role of a graft-versus-lymphoma effect. Leukemia 26:520–526. https://doi.org/10.1038/leu.2011.240

Le Gouill S, Milpied N, Buzyn A, De Latour RP, Vernant JP, Mohty M, Moles MP, Bouabdallah K, Bulabois CE, Dupuis J, Rio B, Gratecos N, Yakoub-Agha I, Attal M, Tournilhac O, Decaudin D, Bourhis JH, Blaise D, Volteau C, Michallet M (2008) Graft-versus-lymphoma effect for aggressive T-cell lymphomas in adults: a study by the Societe Francaise de Greffe de Moelle et de Therapie Cellulaire. J Clin Oncol 26:2264–2271. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.14.1366

Shustov AR, Gooley TA, Sandmaier BM, Shizuru J, Sorror ML, Sahebi F, McSweeney P, Niederwieser D, Bruno B, Storb R, Maloney DG (2010) Allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation after nonmyeloablative conditioning in patients with T-cell and natural killer-cell lymphomas. Br J Haematol 150:170–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08210.x

Shustov A (2013) Controversies in autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in peripheral T/NK-cell lymphomas. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 26:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beha.2013.04.008

Smith SD, Bolwell BJ, Rybicki LA, Brown S, Dean R, Kalaycio M, Sobecks R, Andresen S, Hsi ED, Pohlman B, Sweetenham JW (2007) Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma using a uniform high-dose regimen. Bone Marrow Transplant 40:239–243. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705712

Rodriguez J, Caballero MD, Gutierrez A, Gandarillas M, Sierra J, Lopez-Guillermo A, Sureda A, Zuazu J, Marin J, Arranz R, Carreras E, Leon A, De Sevilla AF, San Miguel JF, Conde E (2003) High dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation in patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma not achieving complete response after induction chemotherapy. The GEL-TAMO experience. Haematologica 88:1372–1377

Beitinjaneh A, Saliba RM, Medeiros LJ, Turturro F, Rondon G, Korbling M, Fayad L, Fanale MA, Alousi AM, Anderlini P, Betul O, Popat UR, Pro B, Khouri IF (2015) Comparison of survival in patients with T cell lymphoma after autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplantation as a frontline strategy or in relapsed disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21:855–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.01.013

Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, Lister TA, Vose J, Grillo-Lopez A, Hagenbeek A, Cabanillas F, Klippensten D, Hiddemann W, Castellino R, Harris NL, Armitage JO, Carter W, Hoppe R, Canellos GP (1999) Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol 17:1244. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1999.17.4.1244

Dearden CE, Johnson R, Pettengell R, Devereux S, Cwynarski K, Whittaker S, McMillan A (2011) Guidelines for the management of mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms (excluding cutaneous T-cell lymphoma). Br J Haematol 153:451–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08651.x

Yam C, Landsburg DJ, Nead KT, Lin X, Mato AR, Svoboda J, Loren AW, Frey NV, Stadtmauer EA, Porter DL, Schuster SJ, Nasta SD (2016) Autologous stem cell transplantation in first complete remission may not extend progression-free survival in patients with peripheral T cell lymphomas. Am J Hematol 91:672–676. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajh.24372

Fossard G, Broussais F, Coelho I, Bailly S, Nicolas-Virelizier E, Toussaint E, Lancesseur C, Le Bras F, Willems E, Tchernonog E, Chalopin T, Delarue R, Gressin R, Chauchet A, Gyan E, Cartron G, Bonnet C, Haioun C, Damaj G, Gaulard P, Fornecker L, Ghesquieres H, Tournilhac O, Gomes da Silva M, Bouabdallah R, Salles G, Bachy E (2017) Role of up-front autologous stem cell transplantation in peripheral T-cell lymphoma for patients in response after induction: an analysis of patients from LYSA centers. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx787

Lunning MA, Moskowitz AJ, Horwitz S (2013) Strategies for relapsed peripheral T-cell lymphoma: the tail that wags the curve. J Clin Oncol 31:1922–1927. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2012.48.3883

Kyriakou C, Canals C, Goldstone A, Caballero D, Metzner B, Kobbe G, Kolb HJ, Kienast J, Reimer P, Finke J, Oberg G, Hunter A, Theorin N, Sureda A, Schmitz N (2008) High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in angioimmunoblastic lymphoma: complete remission at transplantation is the major determinant of Outcome-Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 26:218–224. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2007.12.6219, https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2008.12.6219

Chihara D, Fanale MA, Miranda RN, Noorani M, Westin JR, Nastoupil LJ, Hagemeister FB, Fayad LE, Romaguera JE, Samaniego F, Turturro F, Lee HJ, Neelapu SS, Rodriguez MA, Wang M, Fowler NH, Davis RE, Medeiros LJ, Hosing C, Nieto YL, Oki Y (2017) The survival outcome of patients with relapsed/refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma-not otherwise specified and angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol 176:750–758. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.14477

Lesokhin AM, Ansell SM, Armand P, Scott EC, Halwani A, Gutierrez M, Millenson MM, Cohen AD, Schuster SJ, Lebovic D, Dhodapkar M, Avigan D, Chapuy B, Ligon AH, Freeman GJ, Rodig SJ, Cattry D, Zhu L, Grosso JF, Bradley Garelik MB, Shipp MA, Borrello I, Timmerman J (2016) Nivolumab in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancy: preliminary results of a phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol 34:2698–2704. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2015.65.9789

Pro B, Advani R, Brice P, Bartlett NL, Rosenblatt JD, Illidge T, Matous J, Ramchandren R, Fanale M, Connors JM, Fenton K, Huebner D, Pinelli JM, Kennedy DA, Shustov A (2017) Five-year results of brentuximab vedotin in patients with relapsed or refractory systemic anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Blood 130:2709–2717. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2017-05-780049

Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, Singh Gill D, Linch DC, Trneny M, Bosly A, Ketterer N, Shpilberg O, Hagberg H, Ma D, Briere J, Moskowitz CH, Schmitz N (2010) Salvage regimens with autologous transplantation for relapsed large B-cell lymphoma in the rituximab era. J Clin Oncol 28:4184–4190. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.28.1618

Dietrich S, Boumendil A, Finel H, Avivi I, Volin L, Cornelissen J, Jarosinska RJ, Schmid C, Finke J, Stevens WB, Schouten HC, Kaufmann M, Sebban C, Trneny M, Kobbe G, Fornecker LM, Schetelig J, Kanfer E, Heinicke T, Pfreundschuh M, Diez-Martin JL, Bordessoule D, Robinson S, Dreger P (2014) Outcome and prognostic factors in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma relapsing after autologous stem-cell transplantation: a retrospective study of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Ann Oncol 25:1053–1058. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu097

Kornacker M, Stumm J, Pott C, Dietrich S, Sussmilch S, Hensel M, Nickelsen M, Witzens-Harig M, Kneba M, Schmitz N, Ho AD, Dreger P (2009) Characteristics of relapse after autologous stem-cell transplantation for follicular lymphoma: a long-term follow-up. Ann Oncol 20:722–728. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn691

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rohlfing, S., Dietrich, S., Witzens-Harig, M. et al. The impact of stem cell transplantation on the natural course of peripheral T-cell lymphoma: a real-world experience. Ann Hematol 97, 1241–1250 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-018-3288-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-018-3288-7