Abstract

Purpose

To characterize perceptions of palliative versus futile care in interventional radiology (IR) as a roadmap for quality improvement.

Methods

Interventional radiologists (IRs) and referring physicians were recruited for anonymous interviews and/or focus groups to discuss their perceptions and experiences related to palliative verse futile care in IR. Sessions were recorded, transcribed, and systematically analyzed using dedicated software, content analysis, and grounded theory. Data collection and analysis continued simultaneously until additional interviews stopped revealing new themes: 24 IRs (21 males, 3 females, 1–39 years of experience) and 7 referring physicians (3 males, 4 females, 6–14 years of experience) were analyzed.

Results

Many IRs (75%) perceived futility as an important issue. Years of experience (r = 0.60, p = 0.03) and being in academics (r = 0.62, p = 0.04) correlated with greater perceived importance. Perceptions of futility and whether a potentially inappropriate procedure was performed involved a balance between four sets of factors (patient, clinician, procedural, and cultural). These assessments tended to be qualitative in nature and are challenged by a lack of data, education, and consistent workflows. Referring clinicians were unaware of this issue and assumed IR had guidelines for differentiating between palliation and futility.

Conclusion

This study characterized the complexity and qualitative nature of assessments of palliative verses futile care in IR while highlighting potential means of improving current practices. This is important given the number of critically ill patients referred to IR and costs of potentially inappropriate interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interventional radiologists (IRs) often care for critically ill patients [1, 2], and there are numerous ways interventional radiology (IR) can positively contribute to the care of these patients [3, 4]. However, these procedures can have significant financial and non-financial costs [5], challenging clinicians, patients, families, and payers to consider when an intervention will truly benefit a patient.

Medical interventions that are highly unlikely to provide meaningful benefit are often described as “futile.” This contrasts with “palliative” interventions, which may not extend a patient’s life or treat a disease but provide benefit through symptom relief or increasing the quality of one’s life [4]. Discussions of palliation versus futility often arise in the context of end-of-life care but are not exclusive to this population and can arise throughout IR practice [4]. Truly futile interventions are widely considered unethical because they expose patients to risks without a chance of benefit [6, 7]. They are also costly, both financially [5] and psychologically [8]. For example, Huynh et al. [9] estimated that futile care occurs in 11% of intensive care, accounting for $2.6 million in costs over 3 months, and Furmis et al. [10] found that moral distress from providing care perceived as futile was independently associated with burnout. Nevertheless, it can be challenging to prospectively differentiate palliative from futile care [8, 11], especially considering that these assessments are often qualitative, cultural, and value-laden [12].

Futility in IR remains to be characterized and doing so seems important in light of calls to reduce unnecessary healthcare costs and high rates of burnout [13,14,15,16]. In the authors’ experience, discussions of whether a procedure should be performed tend to first occur between referring clinicians and IRs prior to engaging patients and families, so understanding the perceptions of clinicians seems critical for designing effective interventions to avoid futile care in IR [17]. Thus, this study sought to characterize IRs’ and referring physicians’ perceptions of palliative versus futile care to provide a roadmap for quality improvement.

Materials and Methods

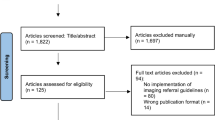

This study was performed in accordance with SRQR reporting guidelines [18]. Recruitment was performed according to grounded theory, a well-validated methodology from the social sciences for exploring complex topics. Recruitment, data collection, and analysis continued simultaneously until additional data stopped revealing new themes. This point of thematic saturation was used to determine the sample size and has occurred after analysis of 24 interventional radiologists (21 males, 3 females, 1–39 years of experience post-fellowship) across 5 practices in the USA: two academic centers, a salary-based compensation private practice group, a fee-for-service private practice group, and a Veterans Affairs (VA) hospital. Demographics are summarized in Table 1. These data were supplemented with focus groups with 7 referring physicians (3 males and 4 females, 6–14 years of experience post-fellowship) at one of the academic centers. Specialties included palliative care (2), oncology (2), critical care (2), and surgical oncology (1).

All data collection and analyses were performed by a single experienced qualitative researcher for data consistency. IRs underwent anonymous interviews about their practice, cases they turn down, and how they make that assessment using the interview script provided in Table 2. The script was designed to establish rapport early in the interview and discuss similar topics across interviews while allowing the interviewee to guide the conversation. This is typical for semi-structured interviewing as it facilitates better exploration of what interviewees view as important with less biased responses [19].

Focus groups were used to collect referring clinician perspectives and facilitate cross talk, using the script provided in Table 2. This was performed after the IR interviews so that common perspectives among IRs could be shared with referring clinicians. Participants’ perceptions of futility and the relevance to IR were discussed prior to sharing common perceptions among IRs so as not to bias the initial responses and allow participants to discuss discrepancies and similarities in their perceptions. Additional focus groups at other sites were not performed due to the limited data that resulted from the initial focus groups.

Interviews and focus groups were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed according to constructivist grounded theory (C-GT) using a dedicated software (NVivo 12, QRS International, Burlington, MA) to identify themes based on the context, wording, and frequency of ideas [20]. This analysis was supplemented with content analysis, where the frequency of ideas and themes are quantified retrospectively [21]. These quantitative data were further analyzed using descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients with statistical significance defined as p = 0.05.

Results

Table 3 provides example quotes for the results below.

Perceived Importance

Many IRs (18/24, 75%) perceived differentiating between palliative and futile care as a relevant and difficult issue for the specialty and quickly offered multiple examples. There was a moderate correlation between perceived and years of experience (r = 0.60, p = 0.03) as well as perceived importance and being in academics (r = 0.62, p = 0.04). Participants earlier in their careers tended to describe not being exposed to many cases that they believed were futile even if they felt the topic was important. IRs in private practice tended to feel that requested interventions were rarely infeasible and even riskier interventions (e.g., stroke thrombectomy) were worth the risk as they were patients’ only option.

Definition

Common examples of futile care included requests for multiple biliary drains in the setting of malignant obstructions or feeding tubes for patients who are bed-bound and nonverbal. Common themes across examples included high cost (financial, pain, or risk of harm) with low probability of meeting the goals of care, repeating previously unsuccessful procedures, unrealistic expectations, and patients who were very old, depressed, near death, and/or had poor performance status. When IRs were asked how they made these assessments, they tended to describe qualitative metrics such as their “sense” of the patient (92%), goals of care (83%), personal experiences (positive or negative) (58%), and risk–benefit ratio (58%).

Motivators

IRs described palliative versus futile care as “complex” and a “balance” between multiple factors. Thematic analysis of the interview transcripts yielded four sets of factors that primarily contribute to IRs’ perceptions of futile care and whether they would perform a procedure perceived as potentially inappropriate. These included patient, clinician, procedure, and cultural factors that are listed in Fig. 1.

Challenges and Solutions

When asked what, if anything, should be done about requests for potentially inappropriate procedures, IRs described a need for more data, addressing financial and cultural incentives to do more, and training on how to make these assessments or navigate discussions with the referring team, patients, and families. Although some state and institutional licensures require ethics training, no IR felt they had received any formal training in how to differentiate between palliative versus futile care. Participants also emphasized that the perceived low-risk nature of IR procedures and IRs’ roles as consultants make these assessments more challenging, that it is often easier to say “yes” rather than “no.” It was also noted that US culture, fee-for-service reimbursement structures, or being in academics may push clinicians and patients to pursue more heroic interventions.

All (7/7) referring physicians were not aware that IRs struggle with requests for potentially inappropriate procedures and assumed IR had policies and guidelines for approaching these requests. They noted that primarily teams are not always expecting an intervention but want patients to hear all their options. Referring physicians emphasized the need for a consistent, multidisciplinary approach that ideally involved the clinician who knew the patient best such as the patient’s oncologist or primary care provider.

Discussion

This qualitative study characterized the complexity of perceptions of palliation versus futility in IR. More experienced IRs in academic practices tended to view futility as a more important issue than those with less experience or those in private practice. This may be due to exposure and environmental incentives. The longer one is in practice, the more opportunities one has to be exposed to poor outcomes from risky, heroic interventions. Likewise, academic practices may be exposed to more complex referrals that push the boundary between palliation and futility. If one’s environment incentivizes intervening and the interventions are felt to be low risk or the patient’s “only option,” it is unlikely that many requests are going to be perceived as futile regardless of the outcome. However, there were multiple additional factors found to contribute to perceptions of futility among IRs and whether an intervention perceived as potentially inappropriate is still performed (Fig. 1). For example, placing a gastrostomy tube may have little to no chance of providing physiologic benefit or achieving the goals of care, but the procedure is performed because feeding is culturally important to the family, the procedure is relatively low risk, and saying “no” may invite multiple phone calls and a lawsuit.

Previous studies of futility have highlighted similar challenges. Clinicians tend to perceive futility as complex and difficult to define [8]. Patients tend to indicate that they would not want heroic measures when presented hypothetical scenarios, yet they also often do not believe physicians can accurately determine when an intervention has little chance of success [7] and feel obligated to exhaust all options, particularly in certain cultures [11, 12]. The crux of the issue seems to be that prospectively identifying something as “futile” relies upon predictions of physiology and value that are rarely clear in the moment. Even if clinicians are able to accurately predict the physiologic impact of an intervention, the value and meaning of potential benefits and risks rest with individual patients and families [12]. Thus, a single rigid definition of “futility” may not be feasible or as helpful as a standard approach that allows clinicians and patients to effectively navigate these requests together on a case-by-case basis.

In response, multiple societies have produced guidelines on how to approach “potentially inappropriate procedures” [6, 7]. They opt for this phrase to better convey that these assessments are preliminary and value laden. Nevertheless, the proposed workflows seem more directed at primary teams than consultant services like IR. Consultants must not only navigate requests for potentially inappropriate procedures with patients and families but primary teams, and often these inter-team dynamics are equally challenging. However, it is important to note that the referring clinicians in this study emphasized that they are not always expecting a procedure when they place a consult so much as advice and a conversation.

Considering these findings, avoiding futile care in IR will require a multidimensional approach aimed at increasing awareness, fostering additional data and education, and developing and trialing consistent workflows. An important first step is increasing awareness by providing forums for IRs and referring clinicians to discuss this issue. National scientific meetings and social media posts tend to celebrate the heroic “saves,” which may underplay risks and costs, pushing less-experienced IRs toward more heroic interventions. Changing the narrative to balance procedural victories with thoughtful debate on long-term outcomes and complications may balance the conversation and provide a safe space for exploring this issue. Similarly, IR practices could host multidisciplinary mortality and morbidity conferences to expose referring clinicians to these challenges and invite discussion of referral patterns and workflows. For example, IRs at the salaried-based private practice group in this study partnered with palliative care to develop an institutional policy of not placing gastrostomy tubes in patients with severe dementia due to growing evidence that these interventions rarely provide any benefit [22].

In addition to awareness, this study highlighted a need for more data and training to empower IRs with tools to identify potentially inappropriate procedures and navigate these requests effectively, both with other clinicians and patients and families. For example, there seems to be a need for more investigations on the cost-effectiveness of palliative IR procedures, in terms of both financial costs and patients’ and families’ perceptions.

Finally, it is paramount that consistent workflows are developed and adopted based on multisociety guidelines [6, 7] as well as the unique challenges for IR characterized in this study. The authors propose a tentative workflow in Fig. 2 where non-emergent IR consults are screened to identify patients with a serious illness. Advance care planning is then used to clarify patients’ and families’ preferences, understanding, and goals, which has been shown to improve satisfaction and reduce distress and costs at the end of life [23, 24]. This step is imperative as it ensures regular, early involvement of patients and families in these decisions. When a potentially inappropriate IR procedure is identified, a collective recommendation is offered as an IR practice to discourage “doctor shopping” within the practice. There should then be a multidisciplinary goal of care discussion that involves a clinician with a longitudinal relationship with the patient as well as an ethics committee or palliative care team as needed to mediate disagreements.

This study had several limitations. The sample size was modest, though typical for the methodologies used. The study did not assess the perspectives of all stakeholders, such as patients and families. This was done to focus the study on the stakeholders who would be targeted by subsequent interventions, e.g., a new clinical workflow and training. This investigation relied on qualitative methods that are well-suited for characterizing complex perceptions but can introduce bias from the researcher serving as an instrument for data collection and analysis. A single-experienced qualitative researcher was used to maximize consistency, but this remains a limitation worth considering.

Conclusion

Differentiating between palliative and futile care in IR is an important but complex issue that is challenged by a lack of data, guidelines, and training on how to approach these cases. In light of these results, the authors propose creating forums for discussing these issues during training and at conferences, generating more data on palliative IR procedures, and piloting a consistent workflow to help IRs navigate consults for potentially inappropriate interventions and avoid futile care. One of the most challenging and important questions in IR may not be “can we do something,” but “should we?”.

References

McCullough HK, Bain RM, Clark HP, Requarth JA. The radiologist as a palliative care subspecialist: providing symptom relief when cure is not possible. Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:462–7.

Pottash M, Aronhime S. Palliative procedures in interventional radiology (S755). J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55:687.

Patel IJ, Bhojwani N, Buethe JY, Robbin MR, Prologo JD. Palliative care procedures for interventional oncologist. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:S128.

Requarth JA. IR and palliative care: a good match. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2015;26:1740–1.

Singavi AK, Szabo A, Thomas JP, et al. Costs of care with liver directed therapy (LDT) and sorafenib (S) in patients (pts) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:383–383.

Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. An official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM policy statement: responding to requests for potentially inappropriate treatments in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:1318–30.

Kon AA, Shepard EK, Sederstrom NO, et al. Defining futile and potentially inappropriate interventions: a policy statement from the society of critical care medicine ethics committee. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1769–74.

Muller R, Kaiser S. Perceptions of medical futility in clinical practice—a qualitative systematic review. J Crit Care. 2018;48:78–84.

Huynh TN, Kleerup EC, Wiley JF, et al. The frequency and cost of treatment perceived to be futile in critical care. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1887–944.

Fumis RRL, Junqueira Amarante GA, de Fatima NA, Vieira Junior JM. Moral distress and its contribution to the development of burnout syndrome among critical care providers. Ann Intensive Care. 2017;7:71.

Swetz KM, Burkle CM, Berge KH, Lanier WL. Ten common questions (and their answers) on medical futility. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:943–59.

Bagheri A. Medical futility: a cross-national study. New Jersey: Imperial College Press; 2013. p. 18.

Charalel RA, McGinty G, Brant-Zawadzki M, et al. Interventional radiology delivers high-value health care and is an Imaging 3.0 vanguard. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12:501–6.

May P, Normand C, Cassel JB, et al. Economics of palliative care for hospitalized adults with serious illness: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:820–9.

Sarwar A, Boland G, Monks A, Kruskal JB. Metrics for radiologists in the era of value-based health care delivery. Radiographics. 2015;35:866–76.

Bundy JJ, Hage AN, Srinivasa RN, et al. Burnout among interventional radiologists. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2020;31(607–613):e601.

Keller EJ, Crowley-Matoka M, Collins JD, Chrisman HB, Milad MP, Vogelzang RL. Fostering better policy adoption and inter-disciplinary communication in healthcare: a qualitative analysis of practicing physicians' common interests. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0172865.

O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2014;89:1245–51.

Spradley JP. The ethnographic interview. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1979. p. 7.

Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. London, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2006. p. 8.

Corbin JM, Strauss AL. In: Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2015. p. 18

American Geriatrics Society Ethics C, Clinical P, Models of Care C. American Geriatrics Society feeding tubes in advanced dementia position statement. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:1590–3.

Klingler C, in der Schmitten J, Marckmann G. Does facilitated advance care planning reduce the costs of care near the end of life? Systematic review and ethical considerations. Palliat Med. 2016;30:423–33.

Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Society of Interventional Radiology’s and Society of Interventional Oncology’s Applied Ethics Working Groups.

Funding

This study was funded by Stanford’s Division of Interventional Radiology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

This study has obtained IRB approval from Stanford University IRB Panel 61, and the need for informed consent was waived.

Consent for Publication

Consent for publication was obtained for every individual person’s data included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keller, E.J., Rabei, R., Heller, M. et al. Perceptions of Futility in Interventional Radiology: A Multipractice Systematic Qualitative Analysis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 44, 127–133 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02675-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-020-02675-3