Abstract

Background

Defining the optimal timing of operative intervention for pediatric burn patients in a resource-limited environment is challenging. We sought to characterize the association between mortality and the timing of operative intervention at a burn center in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Methods

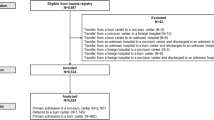

This is a retrospective analysis of burn patients (<18 years old) presenting to Kamuzu Central Hospital from 2011 to 2022. We compared patients who underwent excision and/or burn grafting based on the timing of the operation. We used logistic regression modeling to estimate the adjusted odds ratio of death based on the timing of surgery.

Results

We included 2502 patients with a median age of 3 years (IQR 1–5) and a male preponderance (56.8%). 411 patients (16.4%) had surgery with a median time to surgery of 18 days (IQR 8–34). The crude mortality rate among all patients was 17.0% and 9.1% among the operative cohort. The odds ratio of mortality for patients undergoing surgery within 3 days from presentation was 5.00 (95% CI 2.19, 11.44) after adjusting for age, sex, % total burn surface area (TBSA), and flame burn. The risk was highest for the youngest patients.

Conclusions

Children who underwent burn excision and/or grafting in the first 3 days of hospitalization had a much higher risk of death than patients undergoing surgical intervention later. Delaying operative intervention till >72 h for pediatric patients, especially those under 5 years old, may confer a survival advantage. More investment is needed in early resuscitation and monitoring for this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Burn injuries remain a significant public health problem, causing increased morbidity and mortality worldwide. Globally, the annual incidence of burns requiring management is between 7 and 12 million, ranking as the fourth most common cause of injuries after road traffic accidents, falls, and interpersonal violence [1]. Unfortunately, the burden of burn injury tends to disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where over 95% of severe burns and deaths occur [2, 3]. The impact of these often-preventable burn injuries in LMICs is amplified by a lack of specialty care and shortcomings in health infrastructure [4].

Pediatric burn injury epidemiology in LMICs differs from that in high-income countries (HICs). The overwhelming majority of those bearing the burden of burns in LMICs are children with associated burn sequelae of scars, contractures, and increased risk of skin malignancy [5]. Specifically, children under 15 years in LMICs are more likely to experience a burn injury than children in HICs, typically secondary to scalding or flames [6]. This disparity is especially stark in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where children under 10 years represent 80% of burns. Scald burns account for two-thirds of all burns in sub-Saharan Africa, with the home being the most common location of burn injury [5].

Optimizing pediatric burn management is challenging in SSA. Surgical care is essential in treating severe burn injuries and preventing burn-related complications, and burns comprise many surgical conditions requiring operative intervention [7]. Early excision and grafting remain the standard of care in HICs, particularly for partial- and full-thickness burns [8,9,10]. However, early excision and grafting in SSA may increase mortality [11,12,13]. This may be due to limited resources, shortage of personnel, and operating room space. Consequently, the timing of operative intervention for pediatric burn patients in this resource-limited environment needs to be further delineated. Therefore, we sought to identify the optimal timing of operative intervention for pediatric burns at a burn center in Lilongwe, Malawi.

Methods

This is a retrospective analysis of the burn registry at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH) in Lilongwe, Malawi. KCH is a public tertiary hospital with the only burn center in central Malawi, serving a referral area of approximately nine million people. The KCH Burn Center was established in 2011 and has received significant physical and human resources investments over the last decade [14]. The unit is staffed with a full-time plastic surgeon, clinical officers with burn training, and burn nurses.

This analysis included pediatric patients (<18 years old) admitted to the KCH burn unit from 2011 to 2022. We collected baseline patient characteristics, details of their injuries, presenting vital signs, the timing, and type of operative intervention, and whether the patient lived or died. The primary aim of the study was to determine the difference in mortality based on the timing of operative intervention after burn injury. Crude mortality was defined as in-hospital death. Operative intervention was defined as undergoing excision of the burn with or without skin grafting. Early intervention was defined as surgery within 3 days of arrival at the hospital, and late intervention was greater than 3 days.

Initially, we described the patient population using descriptive statistics. We then used bivariate analysis to compare patients based on whether they had early or late intervention. We used Chi-squared tests for the categorical variables and 2-sample t tests for continuous variables with normal distributions. For variables without a normal distribution, we used the Kruskal–Wallis test. We repeated this bivariate analysis comparing patients who lived and died to identify mortality-related factors. Based on factors identified in our bivariate analysis, we used logistic regression modeling to estimate the odds ratio of death based on whether patients underwent surgery before or after 48 h. We initially included variables identified in our bivariate analysis in the model and removed variables in a stepwise fashion if they changed the final model results by <10%. We report unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval. Using the same model, we also graphed the differences in predicted mortality by increasing age, stratified by operation timing.

We used Stata/MP 18.0 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX) to complete all statistical analyses. The study was approved by The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board and the Malawi National Health Services Review Committee. Consent was waived.

Results

A total of 2502 pediatric patients (<18 years old) were included in the analysis. The median age was 3 years (IQR 1–5), and most were males (58.8%, n = 1418). The median percent total burn surface area (% TBSA) was 13.5% (IQR 8–20), and most burns were caused by scald injury (73.0%, n = 1,816). Only 411 (16.4%) patients underwent operative management with a median time to surgery of 18 days (IRQ 8–34).

Table 1 compares patients undergoing early and late intervention. There were no differences between the two cohorts in sex, type of burn of injury, % TBSA, burn cause, or time to presentation. However, children who underwent delayed surgery were older (4 vs. 3 years, p = 0.025). In addition, in-hospital crude mortality was significantly lower in the late surgery group at 8.4% (n = 33/391) compared to 26.6% (n = 17/64, p < 0.001) in the early surgery group.

We also explored factors associated with mortality. Table 2 compares those who lived and died among patients who underwent surgery. Age was associated with survival, with survivors being older with a median age of 4 years (IQR 2–7.5) compared to 3 years in those who died (IQR 2.0–4.8, p = 0.029). There was also a significant difference in burn size, with survivors having a much lower median % TBSA than those who died (15.0 vs. 25.0, p < 0.001). Lastly, the time to operative intervention was significantly longer for survivors, with a median of 18.0 days (IQR 9–34 days) in the survivor cohort compared to 8.5 days (IQR 2.5–19, p < 0.001) in the cohort that died. There were no differences in sex, burn type, burn case, or time to presentation.

With logistic regression modeling, the unadjusted odds ratio (OR) of mortality for patients undergoing early surgery was 3.85 (95% CI 1.99, 7.44) compared to late surgery. After adjusting for age, sex, % TBSA, and flame burn, the odds ratio for mortality for patients undergoing early surgery was 5.00 (95% CI 2.19, 11.44). Figure 1 demonstrates the adjusted predicted probability of mortality based on age, stratified by time to the operating room. The risk of death was highest for the youngest patients in both cohorts.

Discussion

Given the increased risk of burn injury for pediatric patients in this environment, understanding the differences in outcomes for patients is critical for improving clinical outcomes [6, 15, 16]. Early excision is an essential aspect of burn management in high-resource environments, with evidence that delayed excision is associated with an increased risk of infection, sepsis, and death [4, 9]. In contrast, our study from a limited-resource environment demonstrates an increase in mortality for pediatric burn patients who undergo early surgical management within the first 3 days of hospitalization. Previous work from Malawi showed a significant increase in mortality with early excision and grafting (<5 days) in a cohort of combined adult and pediatric burn patients due to limited burn infrastructure [12]. Our study joins a growing body of literature from LMICs that show early excision may be dangerous in certain environments and should be used cautiously. A 2021 systematic review on this topic concluded that delayed excision was associated with improvement mortality in low-income countries, albeit with low-quality data [11]. Given the relative lack of high-quality data on this subject, prospective data is imperative to fully understand factors leading to worse outcomes for patients.

In our study, patients who underwent early surgery had five times increased odds of mortality compared to delayed excision, representing an improvement from our previously published work. Using updated data in the pediatric population, this study suggests that early resuscitation may have improved at the KCH Burn Center for some patients over the study period after substantial investment in operative capacity and burn care.

Early excision and grafting is an important development in modern burn care that came with increasing our understanding of the pathophysiology of burn injury and refinement in surgical excision and grafting techniques [15]. However, only a third of hospitals in LMICs can provide skin grafting, treat common burn complications, or have the surgical infrastructure to manage advanced burns [8, 17]. While early excision remains the standard of care for burn injuries in HICs, the optimal time for early excision has been controversial in limited-resource settings where various challenges complicate management.

Burn injury size is likely the most important factor contributing to mortality in this environment, as evidenced by the significant difference in %TBSA between those who lived and those that died. However, in the context of operation timing, the etiology of the difference in mortality between those who undergo early versus late excision in LMICs is multifactorial. One contributing factor is the routine delay in care for burn patients. A lack of pre-hospital emergency care services often leads to delays in presentation to a burn center. In addition, many patients in Malawi seek care from a traditional healer prior to evaluation at a local clinic or hospital, which further delay burn resuscitation [18]. These pre-hospital delays lead to delayed resuscitation after presentation, increasing risks for undergoing surgical intervention. It is possible to overcome these challenges in settings with better monitoring capability and intensive care capacity. In contrast, resource limitations in many LMICs exacerbate the complications from delays to presentation.

Our study also showed that the youngest pediatric patients had a higher mortality risk with early excision and grafting. We previously showed that infants and toddlers have a higher mortality rate than older children in Malawi, even when controlling for burn size [19]. Our study proves that mortality is higher in younger pediatric burn patients who undergo early excision in this resource-limited setting. This may be related to the inability to closely monitor and provide resuscitation for very young patients due to equipment, supplies, and human resources limitations. These challenges also extend to the perioperative period, where infants and toddlers may have an increased risk of adverse advents if appropriate anesthesia support is unavailable. Additionally, blood availability in our setting often does not meet patient care demands [20, 21]. Thus, hemorrhage and hypothermia may increase the chance of mortality in the early excision period, especially in younger children. More investment is needed in early resuscitation and monitoring for this patient population.

Our study is limited by its retrospective design, which only includes patients who presented to our facility. Consequently, we could not capture information related to patients with less severe burns that did not require medical attention or severe burns that died before presentation to KCH. Our study also does not have access to anesthesia records, blood transfusion amounts, or cause of death for patients. This data is very hard to reliably collect in this environment and we believe that the available data is still vital for improving burn care in this region. In addition, this is a single-institution study. However, KCH is one of the busiest burn centers in Malawi, with a large catchment population. Despite these limitations, our study provides important evidence for the timing of operative intervention for burn injuries in resource-limited settings.

Conclusion

Children who underwent burn excision and/or grafting in the first 3 days of hospitalization had a much higher risk of death than patients undergoing later intervention. Delaying operative intervention for 72 h for pediatric patients, especially those under 5 years old, may provide a survival advantage. More investment is needed in early resuscitation and monitoring for this patient population.

References

James SL, Lucchesi LR, Bisignano C et al (2020) Epidemiology of injuries from fire, heat and hot substances: global, regional and national morbidity and mortality estimates from the global burden of disease 2017 study. Inj Prev 26:i36–i45

Mock C, Peck M, Krug E et al (2009) Confronting the global burden of burns: a WHO plan and a challenge. Burns 35:615–617

Mock CPM, Peden M, Krug E (eds) (2008) A WHO plan for burn prevention and care. World Health Organization, France

Calland JF, Holland MC, Mwizerwa O et al (2014) Burn management in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities for implementation of dedicated training and development of specialty centers. Burns 40:157–163

Nthumba PM (2016) Burns in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Burns 42:258–266

Stokes MAR, Johnson WD (2017) Burns in the Third World: an unmet need. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 30:243–246

Botman M, Beijneveld J, Negenborn V et al (2019) Surgical burn care in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Burns Open 3:129–134

Gallaher JR, Banda W, Robinson B et al (2020) Access to operative intervention reduces mortality in adult burn patients in a resource-limited setting in sub-Saharan Africa. World J Surg 44:3629–3635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05684-y

Ong YS, Samuel M, Song C (2006) Meta-analysis of early excision of burns. Burns 32:145–150

Atiyeh B, Masellis A, Conte C (2009) Optimizing burn treatment in developing low-and middle-income countries with limited health care resources (part 2). Ann Burns Fire Disasters 22:189–195

Wong L, Rajandram R, Allorto N (2021) Systematic review of excision and grafting in burns: comparing outcomes of early and late surgery in low and high-income countries. Burns 47:1705–1713

Gallaher JR, Mjuweni S, Shah M et al (2015) Timing of early excision and grafting following burn in sub-Saharan Africa. Burns 41:1353–1359

Puri V, Khare NA, Chandramouli MV et al (2016) Comparative analysis of early excision and grafting vs delayed grafting in burn patients in a developing country. J Burn Care Res 37:278–282

Samuel JC, Campbell EL, Mjuweni S et al (2011) The epidemiology, management, outcomes and areas for improvement of burn care in central Malawi: an observational study. J Int Med Res 39:873–879

Organization WH (2008) A WHO plan for burn prevention and care. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241596299. Accessed 15 September 2023

Ahuja RB, Bhattacharya S (2004) Burns in the developing world and burn disasters. BMJ 329:447–449

Gupta S, Wong EG, Mahmood U et al (2014) Burn management capacity in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review of 458 hospitals across 14 countries. Int J Surg 12:1070–1073

Gallaher JR, Purcell LN, Banda W et al (2020) The effect of traditional healer intervention prior to allopathic care on pediatric burn mortality in Malawi. Burns 46:1952–1957

Gallaher J, Purcell LN, Banda W et al (2021) Re-evaluation of the effect of age on in-hospital burn mortality in a resource-limited setting. J Surg Res 258:265–271

Delaney M, Telke S, Zou S et al (2022) The BLOODSAFE program: building the future of access to safe blood in Sub-Saharan Africa. Transfusion 62:2282–2290

Bugge H, Karlsen N, Oydna E et al (2013) A study of blood transfusion services at a district hospital in Malawi. Vox Sang 104:37–45

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Davis, D., An, S., Kayange, L. et al. The Timing of Operative Intervention for Pediatric Burn Patients in Malawi. World J Surg 47, 3093–3098 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-023-07218-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-023-07218-8