Abstract

Background

The safety and effectiveness of expectant management (e.g., watchful waiting or initially managing non-operatively) for patients with a ventral hernia is unknown. We report our 3-year results of a prospective cohort of patients with ventral hernias who underwent expectant management.

Methods

A hernia clinic at an academic safety-net hospital was used to recruit patients. Any patient undergoing expectant management with symptoms and high-risk comorbidities, as determined by a surgeon based on institutional criteria, would be included in the study. Patients unlikely to complete follow-up assessments were excluded from the study. Patient-reported outcomes were collected by phone and mailed surveys. A modified activities assessment scale normalized to a 1–100 scale was used to measure results. The rate of operative repair was the primary outcome, while secondary outcomes include rate of emergency room (ER) visits and both emergent and elective hernia repairs.

Results

Among 128 patients initially enrolled, 84 (65.6%) completed the follow-up at a median (interquartile range) of 34.1 (31, 36.2) months. Overall, 28 (33.3%) patients visited the ER at least once because of their hernia and 31 (36.9%) patients underwent operative management. Seven patients (8.3%) required emergent operative repair. There was no significant change in quality of life for those managed non-operatively; however, substantial improvements in quality of life were observed for patients who underwent operative management.

Conclusions

Expectant management is an effective strategy for patients with ventral hernias and significant comorbid medical conditions. Since the short-term risk of needing emergency hernia repair is moderate, there could be a safe period of time for preoperative optimization and risk-reduction for patients deemed high risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ventral hernias are among the most common surgical pathology seen by clinicians, and ventral hernia repair is one of the most common procedures performed by general surgeons. Once diagnosed, these hernias are either managed through surgical repair or expectant management (e.g., watchful waiting or initial non-operative management). While the outcomes of operative ventral hernia repair are well reported, there is little evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of expectant management. Patients and clinicians may choose expectant management for multiple reasons including: history of significant medical disease, higher probability of surgical complications such as surgical site infections, patient choice, or minimally symptomatic hernias [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Studies of expectant management of other hernia types including inguinal hernias [15, 16] and hiatal hernias exist. However, a limited number of studies focus on expectant management of patients with ventral hernias. Many expectant management studies of patients with ventral hernias have a study design at high risk of bias (e.g., substantial loss to follow-up, small sample size, or retrospective study design) or have limited follow-up duration (2 years or less) [17,18,19,20]. The data from published retrospective studies evaluating crossover to operative management are inconsistent, and the rate of acute presentation, visits to the ER, and changes in symptoms for ventral hernias managed expectantly are not known [21, 22].

The purpose of this study is to report the 3-year outcomes, both patient-reported and clinical, for patients with ventral hernias who were initially managed expectantly.

Methods

We enrolled patients undergoing expectant management of a ventral hernia from 2014–2015 at a hernia clinic in an academic safety-net hospital that cares for uninsured and underserved people after institutional review board (IRB) approval of a prospective study and listing on Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02457364).

Inclusion criterion was any patient being treated with expectant management of a ventral hernia based on patient choice or judgment of the surgeon. Typically, surgeons in this clinic opt for expectant management of patients with an end-stage high-risk medical comorbidity (metastatic cancer, advanced cirrhosis), current smokers, a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1C) > 8%, or a body mass index (BMI) > 33 kg/m2 [23, 24]. At our institution, to be eligible for elective hernia repair, patients must lower their BMI to <33, cease all tobacco products for a minimum of six weeks, maintain a HbA1c of < 8%, and be considered medically optimized for elective surgery by the anesthesia team. If it was improbable a patient would follow-up, such as if they were planning on moving out of the area, they were excluded.

Reason(s) for expectant management and comorbidities were recorded for each patient enrolled as baseline data along with their demographics including ethnicity, age, and gender. Comorbidities included BMI, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), disease of the prostate, aneurysmal disease, immunosuppression, ascites, previous surgical site infection (SSI), as well as number of previous surgeries on their abdomen. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores, based on comorbidities present during the initial consult, were assigned to patients by trained abstractors. A BMI was calculated during the initial visit for each patient. Daily use of a tobacco product determined smoking status. DM was defined as use of diabetic medication or a HbA1c > 6.5%. A history of COPD in the electronic medical record was used to denote a patient with COPD. Prostate disease included having a diagnosis of benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostatitis, or prostate cancer in the medical record. Patient use of immunosuppressive medication, immunosuppressive disease (e.g., HIV), or receipt of chemotherapy within one month was used to define immunosuppression. Imaging or abdominal examination was used to determine the presence of ascites. Patient report or a history of SSI in the electronic medical record defined prior SSI. Patient report was used to determine the number of previous surgeries on their abdomen.

Hernia size was determined using computed tomography (CT) scan measurements. If they did not have a CT scan done, measurements were taken using physical examination. Hernia data obtained included history of ventral hernia repair, whether or not it was recurrent, hernia size (area), hernia type (incisional versus primary), and whether the hernia was located lateral or medial to the semilunar line [25].

Surveys were administered before consultation with a surgeon and during all follow-up visits to obtain patient-reported outcomes. Patients were asked whether or not they desired surgery, and if they did, they were instructed to list reasons explaining why they wished to undergo hernia repair surgery. Patients rated their satisfaction with their abdomen using a Likert scale of 1–10 with 10 meaning satisfied and 1 meaning dissatisfied. They also rated their abdominal pain using a visual analog scale with 10 meaning severe pain and 1 meaning the absence of pain. Finally, they rated the function of their abdomen using the mAAS with 100 meaning good function and 1 meaning poor function [26, 27]. A final score was calculated with the mAAS normalized to a 1–100 scale (eTable 1). Previous studies have demonstrated that the minimally clinically important difference (MCID) for a minor change is seven points and for a major change is 14 points [28].

Three years following initial enrollment, patients were contacted to obtain information about surgeries to their abdomen, current ventral hernia status, hernia repair and whether it was emergent or elective, ER visits due to their hernia after enrollment, and patient-reported outcomes described above.

The rate of conversion to hernia repair was the primary outcome, while secondary outcomes were rates of both elective and emergency repairs, any changes in patient-reported outcomes, and the number of ER visits. Crossover to hernia repair was defined as low risk if <1%/year, but high risk if >10%/year. Emergency repair was low risk if <1%/year, while 1–5% was considered moderate risk. We considered >5%/year high risk. These percentages are based on previous ventral and inguinal hernia non-operative studies [16, 23, 29, 30]. Outcomes for patients who crossed over to operative management of their hernia and those who remained non-operative were analyzed separately. Scores for initial and 3-year follow-up were reported as median (interquartile range), and Wilcoxon matched pairs signed rank test was used to compare differences.

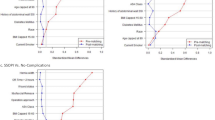

A subgroup analysis by comorbid patients, hernia type, and size was completed. Hernia type was either incisional or primary [25]. Hernia width was used to determine hernia size and was either small, medium, or large (<4, ≥4–10, or ≥10 cm, respectively) [25]. Comorbid patients were defined as any patient with comorbid condition that precluded elective surgery and divided into modifiable (e.g., smoking) or not modifiable (e.g., end-stage cirrhosis). Symptomatic was defined as modified AAS ≤ 80 [28].

Results

In total, 128 patients were enrolled in the study. The most common reason for expectant management was obesity which affected 87 patients (68%). Twenty-three patients (18%) were current smokers. Twenty patients (15.6%) were expectantly managed because of the presence of other comorbidities, 12 (9.4%) by their choice, and two (1.6%) because of surgical complexity. One-hundred patients (78.1%) wanted hernia repair, which was the majority of patients. Eighty-nine (69.5%) desired surgery because of pain from the hernia, 23 (18%) for cosmetic reasons, and 18 (14.1%) for functional limitations. Other less common reasons included wanting concomitant ostomy reversal (5, 3.9%), fear of incarceration/complications (4, 3.1%), wanting an enterocutaneous fistula repaired (2, 1.6%), nausea (2, 1.6%), itching (1, 0.8%), and chronic infection of their mesh (1, 0.8%).

At three years, 84 patients completed the follow-up survey, 38 could not be reached, four patients had died, and two were reached but declined to complete the survey. None of the four deaths were related to hernia complications. The causes of mortality were cancer progression (2), HIV/AIDS complications (1), and advanced cardiac disease (1). Table 1 includes data on patient comorbidities and demographics as well as details about their hernias.

There were few differences between patients who were lost to follow-up and those who responded.

Eighty-four (65.6%) patients were followed up with a median (interquartile range) of 34.1 (31, 36.2) months. Overall, 28 (33.3%) patients visited the ER at least once because of their hernia (due to worsening symptoms with and without bowel incarceration, n = 7, 25% vs. n = 21, 75%), and 31 (36.9%) patients underwent operative management of their hernia. Of those who received surgery, 24 (77.4%) received elective repair, while seven (22.6%) underwent emergent repair (Table 2). Most patients undergoing elective repair met the operative requirements (N = 18, e.g., weight loss). Six patients went to another healthcare system, and two of these were for elective repair. Median (IQR) length of time to elective surgical repair was 14.8 months (11.2, 19.0). Outside institutions performed four of the seven emergent ventral hernia repairs. Records were not available for the six surgeries performed at outside institutions. Obstructions caused the two emergent repairs at our institution. Neither of these patients were found to have necrotic bowel. Among the 31 patients who underwent surgery, two (6.5%) developed a surgical site infection, three (9.7%) developed seroma, one (3.2%) developed wound dehiscence, and four (12.9%) suffered hernia recurrence.

Seven patients had surgery during the follow-up period not related to their hernia (i.e., hernia was not repaired). Eighty of the 84 patients (95.2%) had a physical examination performed during the follow-up period at a mean (range) of 48 months (3–65). Forty-nine patients (58.3%) had another CT scan done in the follow-up period at a mean (range) of 32 months (5–54). Among patients with both a baseline CT scan and a follow-up CT scan prior to surgery (N = 31), the area was 80.9 (107.7) versus 86.3 (116.5), p value 0.094 with a median follow-up of 39 (25) months. One-fourth (25.8%) of patients experienced an increase in their hernia defect size.

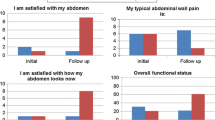

The operative and non-operative median baseline quality of life scores, 28.5 (9.3, 56.9) and 34.0 (11.1, 61.5), respectively, showed no significant difference p = 0.54. No significant change in quality of life was observed for patients undergoing non-operative management; however, patients who converted to operative management had considerable improvement in their quality of life (Fig. 1; Table 3). Patients managed operatively had an improvement in both cosmesis and general satisfaction with their abdomen. The median pain score also decreased in the operative group.

Patients with incisional ventral hernias were more likely to undergo elective repair. Only patients with incisional hernias underwent emergency repair; although this was not statistically significant, it is clinically significant. There was no difference in ER visits or surgical repairs when comparing patients by hernia defect size. This remains true when comparing symptomatic and oligosymptomatic individuals. However, symptomatic individuals were more likely to undergo elective repair (Table 4). More symptomatic individuals had an incisional hernia than a primary hernia (Table 5).

There were five patients with parastomal hernias included in the study; of these three patients completed follow-up. Of those that completed follow-up, all reported at least one ER visit due to their hernia. One patient reported undergoing elective hernia repair, but also reported a recurrence (Table 6).

Discussion

The 3-year risk of emergent repair of patients with ventral hernias initially managed expectantly is moderate (8.3%). One-third of patients visited the ER at least once because of their hernia, one-third ended up converting to operative management, and 7% underwent surgery elsewhere. Most patients who remained non-operative experienced no change in their baseline poor abdominal wall quality of life. It is notable that a greater percentage of patients with ventral incisional hernias as opposed to primary ventral hernias underwent elective and emergent surgeries.

Modifiable risk factors including smoking and obesity were the reason a majority of the patients (64.3%) in this study were managed expectantly; however, only 21.4% of these qualified for elective surgery by modifying their personal risk factors. A couple of patients who were managed expectantly in this study sought elective surgery at another institution. National consensus guidelines for managing patients who have risk factors that can be modified should be adopted along with evaluating preoperative risk-reduction programs for them [23]. In our evolution of patient selection, we currently practice expectant management for patients with (1a) major modifiable comorbid conditions (e.g., morbid obesity, current smoking, uncontrolled diabetes), (1b) severe non-modifiable medical condition (e.g., advanced cirrhosis, advanced cardiopulmonary disease), or (1c) oligosymptomatic; and (2) a hernia at low risk of bowel incarceration or strangulation (non-bowel containing hernia, incarcerated with fat, no prior hernia-related small bowel obstruction).

Early operative management might increase function and satisfaction when compared to expectant management of ventral hernias. Patients who converted to surgical repair had considerable improvement in functional status and patient-reported outcomes, while little improvement was seen in those who remained non-operative. Longer follow-up of these patients is still necessary to monitor for long-term complications and hernia recurrence. Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between operative and non-operative median mAAS baseline quality of life scores, which may indicate baseline satisfaction with their abdominal wall is not the main determinate of surgical intervention. Since the study was not powered to characterize the relationship between hernia symptoms and surgical intervention, a clinically significant difference may not be statistically significant.

Few patients had wound complications and none had bowel strangulation, so surgical outcomes did not seem to be affected by postponing surgery. However, another study showed higher rates of intraoperative perforations, fistulas, and mortality in the watchful waiting group [21]. Of the patients who received emergent repair, there was no difference regarding hernia size, which challenges the belief that small hernias are more likely to incarcerate. More study is needed to accurately identify which patients are more likely to experience incarceration and strangulation of their ventral hernia and should look at specific types of ventral hernia. Outcomes of this study mimic those of inguinal hernias. Our study and those of inguinal hernias have similar crossover rates to operative repair and provide the same reasons for doing so [16, 17]. Despite large similarities, risk of incarceration and emergency surgery is slightly higher in our study than that conducted for inguinal hernias. Due to this difference, we believe close follow-up is warranted for patients with ventral hernias managed expectantly.

This study has several limitations. Patients were followed for a median of 34.1 months during this 3-year follow-up study. Longer follow-up is still necessary; however, a 5-year follow-up study is scheduled. This study was only powered to look at the effectiveness and safety of expectant management for ventral hernias, so it did not compare expectant and early operative management. We did not perform a randomized controlled trial (Clinicaltrials.gov NCT02365194) as we felt elective surgery on high-risk patients was not ethical if they could modify their risk factors to have a lower risk of complications. Despite having a limited power, this study demonstrates patient satisfaction may be improved with hernia repair. The loss to follow-up in this study was about one-third, so including these patients might have shown more emergent and elective hernia repairs along with more ER visits. The total percentage of emergent operation remains unknown, but is in a possible range of 5.5–39.8% versus 8.3% of the 84 included in this follow-up study. A higher rate of emergent operations could have changed the conclusions of the study. Most patient surveys were conducted by phone, which could introduce recall and information bias. The patient population at our county hospital differs significantly from that of other patient populations, so the results may not be generalizable. Since the majority of patients in this study were unemployed, under-insured, or uninsured, there was a high loss to follow-up. Applying the conclusions of this study to different patient populations should be done with caution. Finally, this study included a variety of hernias, and the term ventral hernia includes a very heterogenous group, so simple and complex hernias might have different results and conclusions about expectant management are hard to apply to all ventral hernias. A subgroup analysis by type and size of hernia was done to show any differences between simple and complex hernias; however, the study was not powered to draw conclusions from the subgroups so these results are only hypothesis generating. Additional studies, in particular large, multi-center, prospective trials with long-term follow-up, are warranted as the results may differ by hernia type and other subgroups.

Conclusions

Expectant management is an effective strategy for patients with ventral hernias and significant comorbid medical conditions. There was a moderate (8.3% cumulative risk) risk at three years of requiring surgery emergently, which suggests preoperative optimization and risk-reduction could be an effective strategy for patients deemed high risk for surgery. Operative repair improved patient-reported outcomes; however, patient function and satisfaction was not changed by non-operative management. Expectantly managing patients with severe comorbidities and a ventral hernia could be safe for a short period of time, but it does not increase their quality of life.

References

Fekkes JF, Velanovich V (2015) Amelioration of the effects of obesity on short-term postoperative complications of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 25(2):151–157

Ching SS, Sarela AI, Dexter SP, Hayden JD, McMahon MJ (2008) Comparison of early outcomes for laparoscopic ventral hernia repair between nonobese and morbidly obese patient populations. Surg Endosc 22(10):2244–2250

Sharma A, Mehrotra M, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M, Chowbey PK (2011) Laparoscopic ventral/incisional hernia repair: a single centre experience of 1,242 patients over a period of 13 years. Hernia 15(2):131–139

Tsereteli Z, Pryor BA, Heniford BT, Park A, Voeller G, Ramshaw BJ (2008) Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR) in morbidly obese patients. Hernia 12(3):233–238

Le D, Deveney CW, Reaven NL, Funk SE, McGaughey KJ, Martindale RG (2013) Mesh choice in ventral hernia repair: so many choices, so little time. Am J Surg 205(5):602–607

Fischer JP, Basta MN, Wink JD, Wes AM, Kovach SJ (2014) Optimizing patient selection in ventral hernia repair with concurrent panniculectomy: an analysis of 1974 patients from the ACS-NSQIP datasets. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 67(11):1532–1540

Berger RL, Li LT, Hicks SC, Davila JA, Kao LS, Liang MK (2013) Development and validation of a risk-stratification score for surgical site occurrence and surgical site infection after open ventral hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg 217(6):974–982

Goodenough CJ, Ko TC, Kao LS et al (2015) Development and validation of a risk stratification score for ventral incisional hernia after abdominal surgery: hernia expectation rates in intra-abdominal surgery (the HERNIA Project). J Am Coll Surg 220(4):405–413

Kaoutzanis C, Leichtle SW, Mouawad NJ et al (2015) Risk factors for postoperative wound infections and prolonged hospitalization after ventral/incisional hernia repair. Hernia 19(1):113–123

Finan KR, Vick CC, Kiefe CI, Neumayer L, Hawn MT (2005) Predictors of wound infection in ventral hernia repair. Am J Surg 190(5):676–681

Stey AM, Russell MM, Sugar CA et al (2015) Extending the value of the national surgical quality improvement program claims dataset to study long-term outcomes: rate of repeat ventral hernia repair. Surgery 157(6):1157–1165

Nelson JA, Fischer J, Chung CC et al (2015) Readmission following ventral hernia repair: a model derived from the ACS-NSQIP datasets. Hernia 19(1):125–133

Lovecchio F, Farmer R, Souza J, Khavanin N, Dumanian GA, Kim JY (2014) Risk factors for 30-day readmission in patients undergoing ventral hernia repair. Surgery 155(4):702–710

Koolen PG, Ibrahim AM, Kim K et al (2014) Patient selection optimization following combined abdominal procedures: analysis of 4925 patients undergoing panniculectomy/abdominoplasty with or without concurrent hernia repair. Plast Reconstr Surg 134(4):539e–550e

Fitzgibbons RJ Jr, Ramanan B, Arya S et al (2013) Long-term results of a randomized controlled trial of a nonoperative strategy (watchful waiting) for men with minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias. Ann Surg 258(3):508–515

O’Dwyer PJ, Norrie J, Alani A, Walker A, Duffy F, Horgan P (2006) Observation or operation for patients with an asymptomatic inguinal hernia: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 244(2):167–173

Eid GM, Wikiel KJ, Entabi F, Saleem M (2013) Ventral hernias in morbidly obese patients: a suggested algorithm for operative repair. Obes Surg 23(5):703–709

Cevese PG, D’Amico DF, Biasiato R et al (1984) Peristomal hernia following end-colostomy: a conservative approach. Ital J Surg Sci 14(3):207–209

Cherney DZ, Siccion Z, Chu M, Bargman JM (2004) Natural history and outcome of incarcerated abdominal hernias in peritoneal dialysis patients. Adv Perit Dial 20:86–89

Liu NW, Hackney JT, Gellhaus PT et al (2014) Incidence and risk factors of parastomal hernia in patients undergoing radical cystectomy and ileal conduit diversion. J Urol 191(5):1313–1318

Verhelst J, Timmermans L, van de Velde M et al (2015) Watchful waiting in incisional hernia: Is it safe? Surgery 157(2):297–303

Kokotovic D, Sjolander H, Gogenur I, Helgstrand F (2016) Watchful waiting as a treatment strategy for patients with a ventral hernia appears to be safe. Hernia 20(2):281–287

Liang MK, Holihan JL, Itani K et al (2017) Ventral Hernia management: expert consensus guided by systematic review. Ann Surg 265(1):80–89

Holihan JL, Alawadi ZM, Harris JW et al (2016) Ventral hernia: patient selection, treatment, and management. Curr Probl Surg 53(7):307–354

Muysoms FE, Miserez M, Berrevoet F et al (2009) Classification of primary and incisional abdominal wall hernias. Hernia 13(4):407–414

Krpata DM, Schmotzer BJ, Flocke S et al (2012) Design and initial implementation of HerQLes: a hernia-related quality-of-life survey to assess abdominal wall function. J Am Coll Surg 215(5):635–642

McCarthy M Jr, Jonasson O, Chang CH et al (2005) Assessment of patient functional status after surgery. J Am Coll Surg 201(2):171–178

Cherla DV, Moses ML, Viso CP et al (2018) Impact of abdominal wall hernias and repair on patient quality of life. World J Surg 42(1):19–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4173-6

Fitzgibbons RJ, Jonasson O, Gibbs J et al (2003) The development of a clinical trial to determine if watchful waiting is an acceptable alternative to routine herniorrhaphy for patients with minimal or no hernia symptoms. J Am Coll Surg 196(5):737–742

Sarosi GA, Wei Y, Gibbs JO et al (2011) A clinician’s guide to patient selection for watchful waiting management of inguinal hernia. Ann Surg 253(3):605–610

Funding

No external funding was used to perform this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, A.C., Lyons, N.B., Bernardi, K. et al. Expectant Management of Patients with Ventral Hernias: 3 Years of Follow-up. World J Surg 44, 2572–2579 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05505-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05505-2