Abstract

This study introduces a bio-economic approach to evaluate the influence of local socioeconomic contexts on complex processes of landscape transformation (urbanization, withdrawal of farming with woodland creation and loss in crop mosaics) in a sustainable development perspective. Land-use and socioeconomic indicators (including shares of agriculture, industry and services in total product, per-worker value added, productivity by economic sector, distance from central cities, latitude and elevation) at the local district scale in Italy have been considered together in an exploratory approach based on multivariate statistics. The combined use of land-use and socioeconomic indicators was preferred to more traditional approaches based on single-variable analysis and allows identifying latent factors of landscape transformation at the local scale. Our approach sheds light in the intimate relationship between regional economic structures and land-use change in districts with varying socio-environmental attributes across Italy. Urban-rural divides, coastal–inland dichotomy and the elevation gradient were relevant factors shaping urbanization-driven landscape transformations at the country scale. Indicators of economic structure (and especially industrial production and per-worker productivity of industry and services) were also documented to influence greatly entity and direction of change in the use of land. Discontinuous and dispersed urbanization has been demonstrated to be spatially-decoupled from consolidated (continuous and compact) urbanization, expanding into undeveloped rural areas progressively far away from central cities and being spatially associated with forest land.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global change has significantly altered natural and agricultural landscapes, challenging assessment and conservation tools used to monitoring ecosystem quality and resilience. The sustainability of human societies depends on the wise use of natural resources. Lands contribute to basic human needs like food, clean water, and clean air, and are a major carrier for biodiversity (Keesstra et al. 2016). Landscape transformations in the last century have been molded by mutual relationships between biophysical factors (e.g., topography, climate, soil and water) and the (changing) socioeconomic context (Serra et al. 2008). Rural landscapes have demonstrated to adapt (more or less rapidly) to diversified socioeconomic functions moving towards structural heterogeneity (Detsis et al. 2010). Landscape ‘homologation’ (Frondoni et al. 2011), polarization in ecologically high-quality and low-quality areas (Salvati et al. 2013) and simplification of the spatial relationship between uses of land (Salvati et al. 2017), have been identified as typical—albeit subtle— processes, being observed in regions with high human pressure and urban expansion (Debussche et al. 1999; Bonet 2004; Feranec et al. 2007).

Land-use change is a multifaceted issue with controversial aspects in both patterns and processes, e.g., spatial configuration and its evolution over time (Petit and Lambin 2002), being the result of multiple drivers (Soliman 2004; Paul and Tonts 2005; Christopoulou et al. 2007; Jomaa et al. 2008). In economically-dynamic regions, land-use changes lead to fragmented rural landscapes which were losing rapidly their typical traits because of the decline of crop mosaic (Pelorosso et al. 2009; Geri et al. 2010; Feranec et al. 2010; Cimini et al. 2013). At the same time, peri-urban landscapes have been progressively shaped by dispersed urbanization determining an increasingly mixed use of land and more fragmented spatial structures (EEA 2006; Christopoulou et al. 2007; Hennig et al. 2015).

According to the European Commission (2012), the progressive increase in world population, the growing demand for food and energy and the spatially-asymmetric distribution of natural resources stimulate a reflection on interpretative frameworks supporting strategies aimed at harmonizing socioeconomic targets to environmental requirements. Bio-economic approaches are important when addressing these challenges by ensuring conditions for local sustainability and supporting rural development, the potential for reducing emissions of greenhouse gases, eco-compatible production, and the diffusion of innovation industry across the entire value chain (EEA 2013).

The informed assessment of land-use changes requires an in-depth analysis of the socioeconomic context underlying different trajectories of landscape modification (Soliman 2004; Theobald and Romme 2007; Jomaa et al. 2008; Shrestha et al. 2012). Existing data are generally insufficient for an improved understanding of past and actual land-use structures and should be integrated with spatial information clarifying the main causes of transformation (Committee on Global Change Research 1999). In this regard, containment of land take from urbanization has become a major challenge requiring permanent monitoring based on homogeneous classification and analysis criteria (Martinez-Fernandez et al. 2015; Quatrini et al. 2015).

Long-term observation and mapping of land-use spatial distribution are essential to evaluate dimensions, consequences and causes of landscape transformation and to predict future trends (Houet et al. 2010; Loveland et al. 1999, 2002). Monitoring tools allow to identify in a quick way and at low cost key landscape patterns and their structural and functional changes (Corona et al. 2012). To detect and quantify land-use change at an enough detailed spatial scale, the CORINE (Coordination of Information for the Environment) land cover (CLC) project, a pan-European initiative promoted by the European Environment Agency (EEA), has been applied successfully to monitor landcover dynamics in European countries. CLC maps cover 36 European countries with a homogeneous land classification in the time interval between 1990 and 2012. Data on land-use change derived from CLC maps evidence that the expansion of urban and forest land has led to a progressive loss of cropland. For example, change in land-use between 2000 and 2006 involved 1.3% of the total land stock in Europe (68,353 km2 out of 5.42 million km²). Monitoring land-use in Europe through the CLC maps allows a diachronic analysis of the latent relationship between environmental and socioeconomic contexts, based on indicators assessing the role of spatially-differentiated drivers of change (Geist and Lambin 2002).

In the Mediterranean region, anthropogenic factors (such as urbanization, late industrialization, tourism-related activities, forest fires and deforestation, land abandonment, and crop intensification) have determined important changes in the use of land (Bonet 2004; Sluiter and de Jong 2007; Feranec et al. 2010). Rural landscapes underwent considerable modifications, including forest recovery in mountainous areas (Falcucci et al. 2007; Salvati and Zitti 2012; Cimini et al. 2013), sprawl-driven habitat fragmentation in coastal areas and around the major cities (Sallustio et al. 2015; Salvati and Ferrara 2015; Gasparella et al. 2017), and change from extensive to intensive agriculture in both hilly and flat areas (Salvati and Colantoni 2015). At the same time, local socioeconomic contexts have been frequently constrained by biophysical factors, such as climate aridity, poor soil and limited vegetation cover, steep topography and diffused vulnerability to soil erosion and landslides (Salvati et al. 2013). Based on these premises, evaluating spatial relationships between land-use structure and socioeconomic background appears to be a complicated research issue that needs further investigation.

By integrating land-use data derived from CLC maps and statistical indicators in an exploratory data mining approach, our study aims to identify the main socioeconomic factors associated to changes in the use of land in Italy over the last two decades (1990–2012). Italy displays a territorial background representative of southern European countries, with recent land-use dynamics characterized by expanding urban areas and forests and declining cropland. Moreover, the Italian territory hosts high environmental, cultural and socioeconomic diversity with regional disparities that make a within-country analysis very informative for inference on a broad geographical scale. Distinctively, this work aims to clarify the influence of multifaceted local contexts on complex processes of land-use transformations, interpreting landscape complexity based on three dimensions: socioeconomic background, biophysical conditions, and candidate drivers of change. Specific objectives of this study are: (i) to analyze for the first time in Italy the evolution of land-use in a bio-economic perspective and (ii) to identify the main geographic gradients influencing changes in the use of land at the district scale in a Mediterranean country. Results of this study may provide informative elements and operational tools supporting sustainable land management strategies aimed at containing urban expansion and mitigating landscape fragmentation in economically-dynamic regions with high environmental potential, biodiversity and relict natural habitats.

Methodology

Study Area

Italy is located in southern Europe, in the middle of the Mediterranean basin. The country’s area (301,330 km2) is composed of nearly 23% lowlands, 42% uplands, and 35% mountainous areas, being administered by 20 regions, 110 provinces and more than 8000 municipalities (Salvati and Colantoni 2015). The economic structure is based on traditional services including construction, commerce and public sector and advanced services (research and development, telecommunication, real estate, banking and finance). Italy is geographically divided into macro-regions (Northern, Central, and Southern Italy) reflecting important divides in local economic structures reflected in different levels of income and wealth, population density and unemployment. Northern Italy, separated from Europe by the Alps, extends the entire Po valley being one of the most affluent regions in Europe. Central Italy, separated from Northern Italy by the Apennine Mountains, is polarized in urban and rural areas and characterized by traditional agricultural landscapes in mountainous districts. Southern Italy, including islands of Sicily and Sardinia, is classified as an economically-disadvantaged region still subsidized by European Union. Italy is also characterized by relevant environmental disparities between northern and southern regions, with differences observed in climate, landscape, vegetation, soil, and cropping systems (Salvati and Carlucci 2011).

Spatial Analysis’ Unit

This study investigates land-use structure and the socioeconomic background at the geographical scale of local districts in Italy. Local labor market areas (LLMAs) including a variable number of municipalities ranging between 5 and 10 on average, were selected as appropriate spatial units identifying economically-homogeneous districts. A total of 686 local labor system (LLS) districts, officially defined by the Italian National Statistical Institute (Istat) according to data collected in 2001 National Census of Population and Household (Istat 2006), are considered in this study. LLS districts were defined on a functional basis, the key criterion being the proportion of commuters who cross the district boundary on their way to work. Being a synonym for LLMAs, the LLS districts are sub-regional areas where activities can find the largest workforce to match with the offered jobs. These spatial domains respond to the need for meaningful comparison of sub-regional labor market areas for statistical reporting and analysis (Pellegrini 2002).

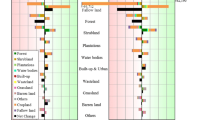

Land-Use Indicators

The land-use structure of Italy was assessed at four points in time (1990, 2000, 2006, and 2012) based on the available CLC pan-European digital cartography (EEA 2006). CLC maps were derived from photo-interpretation and digitalization of Landsat satellite imagery following harmonized procedures based on a common classification system and producing 1:100,000 maps with 25 ha minimum mapping unit and 100 m minimum width of linear elements (Salvati et al. 2013). The standard CLC nomenclature includes 44 land cover classes grouped into a three-level hierarchy. A total of eight land-use indicators were computed at the district scale including (i) the share of discontinuous settlements (CLC class 112) in total built-up area, percent areas of (ii) urban land (CLC class 1), (iii) agricultural land (CLC class 2), (iv) forest land (CLC class 3.1) and (v) other non-forest natural land (CLC classes 3.2–3.3) in total landscape, as well as the mean size of (vi) urban, (vii) agricultural, and (viii) natural (forest and non-forest) patches in the landscape.

Contextual Variables

The socioeconomic indicators considered in this paper (see list in Table 1) were derived at the district scale from statistical data provided by the Italian National Institute of Statistics (Istat 2006) referring to an intermediate point in the studied time interval (year 2001). A total of 24 indicators were calculated including per-head and per-worker district value added, share of agricultural and industrial value added in total district product, labor productivity by sector (agriculture, industry, and services), districts specialized in manufacturing or tourism, industrial clusters and economically unspecialized districts. Additional variables assessing average elevation (taken as a proxy of district’s accessibility), population density, the prevalent urban or rural condition, and the geographical position of each district in northern/central Italy or in southern Italy, were finally considered.

Statistical Analysis

A data mining approach was developed in this study to analyze jointly land-use indicators and selected variables assessing the most relevant socioeconomic characteristics of local districts in Italy (Fig. 1). The approach incorporates descriptive, inferential and multivariate statistics including rank correlation analysis, multiway factor analysis and principal component analysis with supplementary variables.

Descriptive statistics, maps and non-parametric correlation analysis

Socioeconomic divides and changes over time in the land-use structure of Italy were analyzed using maps illustrating the spatial distribution of representative indicators. Land statistics (percent class area and mean patch size) were computed by year and land-use (see section 2.3). The relationship between land-use indicators and the variables assessing socioeconomic background in each district (see section 2.4) was studied using pair-wise non-parametric Spearman rank correlation analysis testing for significance at p < 0.05 after Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Multiway factor analysis

A Multiway Factor Analysis (MFA) was run with the aim to obtain a comprehensive overview of spatio-temporal changes in land-use between 1990 and 2012 based on 8 indicators measured diachronically (1990, 2000, 2006, 2012) at every district in the study area. The MFA identifies complex structures in higher-order datasets (Coppi and Bolasco 1988), allowing for an indirect measure of the impact caused by external factors (Kroonenberg 2008). The analysis associates variables with similar spatio-temporal patterns on a few relevant components with eigenvalue > 1 using loadings that range from −1 (negative correlation) to 1 (positive correlation). Component scores were mapped, allowing identification of clusters of districts characterized by a similar spatio-temporal pattern of landscape transformation (Escofier and Pagès 1994). The relationship between the extracted MFA components and the selected socioeconomic variables (see section 2.4) was studied using pair-wise non-parametric Spearman rank coefficients testing at p < 0.05 after Bonferroni’s correction for multiple comparisons.

Principal component analysis

A principal component analysis (PCA) was used in this study to summarize the most relevant socioeconomic dimensions underlying changes in the use of land at the geographical scale of LLS districts in Italy, incorporating the factor scores selected in the previous MFA (see 2.5.2). The PCA is a multivariate analysis suited to describe multiple relationships among large sets of indicators, allowing to eliminate (or reduce) the redundancy of the information due to high levels of serial autocorrelation within the data. Having run a PCA based on correlation matrix, the number of relevant axes was chosen by retaining components with eigenvalue > 1. The Keiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, which tests whether the partial correlations among variables are small, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, which tests whether the correlation matrix is an identity matrix, were considered to assess the quality of analysis’ outputs. An example of a PCA applied to environmental and socioeconomic factors in Italy is proposed in Salvati and Ferrara (2015).

Results

Mapping Socioeconomic Divides in Italy

Figure 2 illustrates the spatial distribution of selected socioeconomic variables in Italian districts. Maps revealed important divides between northern and southern regions. The highest population density was observed in metropolitan districts such as Rome, Milan and Naples. Following the elevation gradient, the lowest density was found in southern Italian districts with steep topography, especially Sardinia and Calabria, and in marginal rural areas of central Italy. On average, districts situated along the Adriatic sea coast have experienced greater population density and higher rates of population growth compared with those observed along the Tyrrhenian sea coast. Socioeconomic divides between northern and southern Italy are well reflected in the spatial distribution of average district per-capita income. As a result, economically-unspecialized districts were concentrated in southern and central Italy. Tourism-specialized districts were situated in Trentino Alto Adige and Sardinia, with sporadic cases in the Apennines and along the Tyrrhenian sea coast. “Made in Italy” districts (specialized in high-quality manufacturing and handicraft productions) were diffused over north-eastern and central regions of the country being more scarce in southern Italy. Districts with a predominant industrial structure specialized in heavy manufacturing were concentrated in north-western and south-eastern of Italy. Districts with high per-worker productivity in industry were concentrated in northern and central Italy districts. Per-worker productivity in the primary sector was found higher in northern Italian districts (mainly situated in the Po plain) than elsewhere in the country. Finally, the spatial distribution of per-worker productivity in services was relatively uniform over Italy, with the highest values observed in some metropolitan areas (e.g. Milan, Rome, Venice). According to these evidences, the differential wealth distinguishing northern districts from southern districts derives largely from industry; districts with the share of agriculture in total product above 30% were extensively observed in southern Italy. Services’ productivity is strongly correlated with urban hierarchy in Italy.

A Descriptive Analysis of Land-Use Changes in Italy (1990–2012)

Table 2 reports long-term changes in the use of land based on CLC mapping. Results of our analysis evidence a significant expansion of artificial surfaces (0.8%) and forests (0.4%), with a moderate decline in crop mosaic (−0.3%) and a huge decline in non-forest semi-natural areas (−1%), slightly increasing arable land (0.1%) and stable tree crop area (0%). Districts with increasing built-up area between 1990 and 2012 (118 out of 686 districts totalizing 1.5% average growth rate) were generally concentrated in the most accessible districts of Italy and especially (i) around the largest metropolitan areas (Rome, Milan, Naples, Firenze, Cagliari, Catania), (ii) along the Po Valley in the triangle between Turin, Venice and Bologna) and (iii) along the Adriatic sea coast, from Marche to Apulia (Fig. 3). The progressive expansion of discontinuous settlements (CLC class 112) was spatially-decoupled from consolidated urban areas. The share of discontinuous settlements in total landscape area was above 5% in 131 districts mainly situated across the Alps, along sea coasts, and in southern Italy. The relationship between share of built-up area in total landscape at the beginning of the study period (1990) and percent change over time (1990–2012) in discontinuous urban fabric at the district scale in Italy (Fig. 4) was not significant (r s = 0.06, p > 0.05, n = 686).

A Multidimensional Analysis of Land-Use Structure

The outcomes of a multiway factor analysis run on a diachronic dataset of land-use indicators were presented in Table 3 and indicate a relatively stable structure of land-use in Italy with important changes at the local scale as a result of urbanization, (spontaneous or human-driven) withdrawal of farming with woodland creation and loss in crop mosaics and non-forest semi-natural land. Factor 1 (39.6% in total variance) identified a typical rural gradient oriented along elevation and discriminating districts with prevailing agricultural land-use from districts whose landscape is dominated by forests and other semi-natural classes. This factor also highlighted the moderate association of urban areas with agricultural districts in contrast with the spatial distribution of less populated districts associated to a land-use structure dominated by large patches of natural (forest and non-forest) land classes.

The highest (positive) factor scores were attributed to mountainous districts across the Alps and the Apennines contrasting with the lowest (negative) scores attributed to accessible, flat or coastal districts in Po plain, Apulia and along the Tyrrhenian sea coast (Fig. 5). Land-use structure remained substantially stable during the study interval with a moderate increase in loadings of urban, forest and other semi-natural areas and a slight decrease in loading of agricultural areas. These limited changes in the use of land were reflected into a higher polarization in districts with high (>2.5) and low (<2.5) scores in 2012 in respect with 1990. The only relevant change between 1990 and 2012 was observed for the share of discontinuous settlements in total landscape which received a positive loading on Factor 1 for the first time in 2012. This result indicate how the spatial distribution of discontinuous settlements in Italy was progressively modified over the last two decades being increasingly associated to forest land, in agreement with evidences from non-parametric correlation analysis illustrated in section 3.2. These findings suggest that discontinuous urbanization was expanding into rural areas progressively further away from urban areas and metropolitan districts dominated by cropland, as it was observed in earlier decades.

The spatial distribution of factor scores (left: factor 1; right: factor 2) in Italy resulting from a Multiway Factor Analysis of land-use variables (see Table 1)

Factor 2 (20.9% in total variance) identified a typical urban gradient with metropolitan districts receiving the highest (negative) scores. Between 1990 and 2006, continuous and discontinuous urbanization processes has a coherent spatial distribution in Italy (both receiving negative scores). In 2012, discontinuous urbanization was no longer associated to Factor 2. The spatial distribution of Factor 2 scores reflected the Italian urban hierarchy distinguishing metropolitan districts from inland and marginal districts mainly situated in southern Italy. However, the number of marginal districts (score > 2.5) decreased in 2012 in respect with 1990.

Non-Parametric Correlations between Land-Use Indicators and the Local Socioeconomic Background

Correlation pattern between land-use indicators and contextual variables assessing socioeconomic background in each local district is particularly complex (Table 4). Spatial distributions of urban areas and discontinuous settlements were associated to different contextual variables. The share of discontinuous settlements in total landscape increased with elevation and decreased in southern Italy districts and in districts with below-average population density (correlation observed for 1990 only). In both study years (1990 and 2012), the percentage of total built-up areas in district surface area increased with population density, population growth rate, number of municipalities in each district, productivity of industry and services, average district value added and decreased with elevation, share of agriculture in total district product, distance from the provincial capital city and lack in economic specialization (industry or service). The percentage of agricultural land in district surface area increased with population density and share of primary sector in total district product decreasing with elevation and specialization in tourism.

Conversely, the percentage of forest land in district surface area decreased with population density and increased with elevation, being systematically lower in southern Italy districts than in northern Italy districts. Non-forest, semi-natural land is more diffused in tourism-specialized, mountainous districts at considerable distance from regional and provincial capital cities. Class area decreased in industrial districts with medium-high population density and considerable share of industry and services in total product. Mean size of urban patches decreased along the elevation gradient, being the highest in flat district with considerable population density and growth rate, productivity of industry and services, and the lowest in agricultural districts far away from central cities. Mean size of cropland patches increased with total district surface area, population growth rate, productivity of all economic sectors, average district value added and closeness to a provincial capital city. Mean size of forest patches showed a reverse correlation pattern in respect of what was observed for agricultural land with a higher number of significant correlations found for 2012 compared with 1990, confirming the increasing polarization in districts dominated by forest and agricultural landscapes well evidenced in the results from Multiway Factor Analysis, and possibly indicating a latent shift towards landscape simplification and homogenization in rural districts.

Contextual Factors Underlying Changes in the Use of Land

A PCA was carried out to investigate the relationship between the socioeconomic background and the most relevant changes in land-use structure derived from the MFA (Fig. 6). The analysis extracted 3 components explaining 53.8% of the total matrix variance. Component 1 (26.8%) illustrates the urban–rural divide in Italy being correlated with MFA Axis 2 (urban gradient): positive and negative scores respectively indicate more densely populated areas and rural, mountain and less accessible districts. Per-worker productivity of services and industry received the highest (positive) loadings. Distance to provincial capital and economically unspecialized districts in turn received (negative) loadings. Component 2 (16.3%) identified an elevation gradient associated with the percentage of mountain municipalities, tourism specialized districts (positive loading) and population density (negative loading) and showing a significant correlation with MFA axis 1 (forest vs agricultural land-use). Component 3 (10.7%) discriminated districts with a high share of services in total product (positive loading) from the most industrialized districts (negative loading) with no specific relationship with any land-use gradient identified by Multiway Factor Analysis.

The spatial distribution of component scores (left: PC 1; middle: PC2; right: PC 3) in Italy resulting from a Principal Component Analysis of socioeconomic variables (see Table 5)

Discussion

This study assesses landscape dynamics integrating land-use change detection with an exploratory analysis of socioeconomic contexts varying across local districts in Italy. According to Geist and Lambin (2004), identifying drivers of change requires an in-depth understanding of how specific socio-environmental factors interact to influence land-use decisions. Being intended as territorial units consisting of contiguous municipalities, local labor market areas are geographically and statistically homogeneous analysis’ domains appropriate to investigate how socioeconomic background may influence land-use structure and changes over time. Local labor systems reflect homogeneous districts of economic interest (Pellegrini 2002) and were frequently used to investigate the latent relationship between regional development, urban competitiveness and local environmental conditions (Salvati et al. 2017).

Results of our study indicate urbanization (and especially discontinuous urban growth), (spontaneous or human-driven) withdrawal of farming with woodland creation and loss of crop mosaics as the most relevant landscape transformations in Italy, in accordance with earlier evidences found at both regional and country scale (Kasanko et al. 2006; Falcucci et al. 2007; Frondoni et al 2011, Hennig et al. 2015; Sallustio et al. 2015). The expansion of discontinuous settlements was spatially decoupled from consolidated urban areas; this allowed identifying socioeconomic processes at the base of such transformation (Salvati and Carlucci 2011). This phenomenon is likely due to the fact that recent trends of urban expansion in Italy were concentrated in areas progressively further away from metropolitan regions (Catalán et al. 2008; La Greca et al. 2011). Urbanization was associated with ‘naturbanization’ phenomena, evidencing the importance of natural amenities, landscape esthetics and quality of life attracting urban population to move to rural areas (Prados 2005; Serra et al. 2014).

The descriptive analysis of change in natural and semi-natural land-use classes has evidenced the progressive expansion of forests (class CLC 3.1 increased by 0.1% from 1990 to 2012) into abandoned cropland, possibly altering landscape diversity of agricultural mosaics. This phenomenon was motivated with the spontaneous colonization of marginal land in hilly and mountainous districts following depopulation and farmland abandonment (e.g. Corona et al. 2008; Barbati et al. 2013; Cimini et al. 2013). This land abandonment has been the result of socioeconomic changes, but the impact will also be environmental as the goods, services, and resources the abandoned land offers to humankind will change (Mol and Keesstra 2012; Keesstra et al. 2016; Romero-Díaz et al. 2017). According to Tasser et al. (2007), forest expansion into farmland may have positive environmental impacts (e.g. improved soil conservation, containment of water erosion, higher carbon sequestration). However, as we have seen with our analysis, it counterbalanced with the reduction and fragmentation of crop mosaics, which may result in a loss of biodiversity, cultural heritage and aesthetical attractiveness of rural landscapes (Cimini et al. 2013).

Our analyzes also highlight that, together with depopulation of inland hilly and mountainous districts tourism development has resulted in population growth along Mediterranean coastal areas, as settled other studies confirm (Saurì and Breton 1998; García-Ruiz et al. 2011; Serra et al. 2008; Falco 2017; among other). As the results of correlation analysis clearly show for Italian coastal districts, the ecological fragility of Mediterranean littoral areas is the result of increased human pressure coupled with specific biophysical drivers, including climate change (e.g. Schlacher et al. 2008, 2014; Malavasi et al. 2013). For example, between 1990 and 2012, our study underlines how the Adriatic sea coast in Italy became progressively more densely populated than the Tyrrhenian sea coast, confirming earlier evidences from Romano and Zullo (2014) indicating the Adriatic sea coast in northern and central Italy as ecologically fragile and particularly exposed to human pressure. The increased human pressure in coastal districts is a cause of landscape fragmentation, decline of natural habitats, isolation and loss of ecological quality in relict natural fragments (Tomaselli et al. 2012; Malavasi et al. 2014). However, earlier studies have proved that landscape fragmentation and land-use change are spatially decoupled in Italy: patch fragmentation increased with the percent area of both forests and urban fabric, with agricultural land being the most attractive for dispersed urbanization (Salvati and Colantoni 2015). Traditional, unfragmented rural areas have been progressively relegated into specialized and less accessible territories, determining an increased polarization in local districts respectively dominated by crop mosaics and forests, with a reduction of landscape biodiversity (Stürck et al. 2015; Gasparella et al. 2017; Tomao et al. 2017). Furthermore, the high intensity of use of land for agriculture may result in degraded soils as a consequence of heavy machinery, soil erosion and loss of fertility (Galati et al. 2016; Parras-Alcántara et al. 2016; Rodrigo Comino et al. 2016).

Taken together, the exploratory analysis proposed in our study identifies rural–urban, coastal–inland and elevation as the main geographical gradients influencing landscape transformations in Italy, being related to distinct socioeconomic factors of change. The role of these gradients has been already investigated, e.g., in the assessment of ecosystem services (Kroll et al. 2012; Larondelle and Haase 2013). However, the comprehensive evaluation of the underlying factors sheds further light on local-scale processes of landscape transformation, providing an enriched informative base to socioeconomic policies aimed at stimulating a sustainable development of local districts (e.g., Theobald and Romme 2007).

This study finally underlines the importance of medium- and high-resolution land-use data as a base for land statistics at all geographical levels and to support decision-makers in the sustainable management of rural territories (Jansen and Di Gregorio 2004; Marchetti et al. 2015). The CLC initiative provides a platform for information and monitoring at a sufficiently disaggregated spatial scale. Spatial domains of different size, political entity and administrative rule are important for the definition of land-use regional models that allow investigating multiple territorial aspects, the local socioeconomic context and biophysical factors reflected into specific geographical gradients. Based on our results, relevant geographical gradients can be interpreted as homogeneous operational spatial units for comprehensive bio-economic analysis of landscape in relation to the joint action of multiple drivers of change. Although relevant changes in the use of land have been observed between 1990 and 2012 (e.g. urban sprawl, withdrawal of farming with woodland creation, loss of crop mosaics), the importance of geographical gradients (especially elevation and latitude) in shaping land-use structure of Italy maintained substantially stable.

Conclusion

In this study an exploratory data analysis was effectively applied to mixed eight land-use indicators derived from CLC maps and related socioeconomic indicators derived from various statistical sources, in order to investigate land-use spatial dynamics during 22 years (1990–2012), in relation with the dominant socioeconomic background at Italian district scale. Through the use of descriptive analysis and non-parametric correlation, we have identified the main geographic gradients influencing changes in the use of land in Italy. Rural–urban divides, coastal–inland dichotomy and the elevation gradient were relevant factors shaping urbanization-driven landscape transformations at the country scale. Our study provides an original framework approaching the analysis of landscape transformations in Mediterranean Europe vis à vis relevant bio-economic factors at the local scale. The proposed approach contributes to a better understanding of the latent relationship between regional economic growth and land-use structure in the light of sustainable development of socio-environmental local systems. Our approach finally provides an operational base orienting future research in the comparative analysis of regional and local drivers of change in land-use.

References

Barbati A, Corona P, Salvati L, Gasparella L (2013) Natural forest expansion into suburban countryside: gained ground for a green infrastructure? Urban For Urban Green 12(1):36–43

Bonet A (2004) Secondary succession of semi-arid Mediterranean old-fields in south-eastern Spain: insights for conservation and restoration of degraded lands. J Arid Environ 56:213–233

Catalán B, Saurí D, Serra P (2008) Urban sprawl in the Mediterranean?: patterns of growth and change in the Barcelona Metropolitan Region 1993–2000. Landsc Urban Plan 85(3):174–184

Christopoulou O, Polyzos S, Minetos D (2007) Peri-urban and urban forests in Greece: obstacle or advantage to urban development? J Environ Manage 18:382–395

Cimini D, Tomao A, Mattioli W, Barbati A, Corona P (2013) Assessing impact of forest cover change dynamics on high nature value farmland in Mediterranean mountain landscape. Ann Silvic Res 37:29–37

Committee on Global Change Research (1999) Global Environmental Change: Research Pathways for the Next Decade. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Coppi R, Bolasco S (1988) Multiway data analysis.. Elsevier, North-Holland

Corona P, Barbati A, Tomao A, Bertani R, Valentini R, Marchetti M, Perugini L (2012) Land use inventory as framework for environmental accounting: an application in Italy. iForest 5(4):204

Corona P, Calvani P, Scarascia Mugnozza G, Pompei E (2008) Modeling natural forest expansion on a landscape level by multinomial logistic regression. Plant Biosyst 142:509–517

Debussche M, Lepart J, Dervieux A (1999) Mediterranean landscape changes: evidence from old postcards. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 8(1):3–15

Detsis V, Ntasiopoulou G, Chalkias C, Efthimiou G (2010) Recent insular Mediterranean landscape evolution: a case study on Syros, Greece. Landsc Res 35(3):361–381

EEA (2006) Urban Sprawl in Europe. The Ignored Challenge. Report 10. European Environment Agency, Copenhagen, http://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/eea_report_2006_10

EEA (2013) GIO Land High Resolution Layers (HRLs)—summary of product specifications. http://land.copernicus.eu/user-corner/technical-library/gio-landhigh-resolution-layers-hrls-2013-summary-of-product-specifications

Escofier B, Pagès J (1994) Multiple factor analysis (AFMULT package). Comput Stat Data Anal 18(1):121–140

EU Commission (2012) Innovating for sustainable growth: a bioeconomy for Europe. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the regions, Brussels, p 13

Falco E (2017) Protection of coastal areas in Italy: Where do national landscape and urban planning legislation fail? Land Use Policy 66:80–89

Falcucci A, Maiorano L, Boitani L (2007) Changes in land-use/land-cover patterns in Italy and their implications for biodiversity conservation. Landsc Ecol 22(4):617–631

Feranec J, Hazeu G, Christensen S, Jaffrain G (2007) Corine land cover change detection in Europe (case studies of the Netherlands and Slovakia). Land Use Policy 24(1):234–247

Feranec J, Jaffrain G, Soukup T, Hazeu G (2010) Determining changes and flows in European landscapes 1990–2000 using CORINE land cover data. Appl Geogr 30:19–35

Frondoni R, Mollo B, Capotorti G (2011) A landscape analysis of land cover change in the Municipality of Rome (Italy): Spatio-temporal characteristics and ecological implications of land cover transitions from 1954 to 2001. Landsc Urban Plan 100(1):117–128

Galati A, Crescimanno M, Gristina L, Keesstra S, Novara A (2016) Actual provision as an alternative criterion to improve the efficiency of payments for ecosystem services for C sequestration in semiarid vineyards. Agric Syst 144:58–64

García-Ruiz JM, López-Moreno JI, Vicente-Serrano SM, Lasanta-Martínez T, Beguería S (2011) Mediterranean water resources in a global change scenario. Earth-Sci Rev 105(3-4):121–139

Gasparella L, Tomao A, Agrimi M, Corona P, Portoghesi L, Barbati A (2017) Italian stone pine forests under Rome’s siege: learning from the past to protect their future. Landsc Res 42(2):211–222

Geist HJ, Lambin EF (2002) Proximate causes and underlying driving forces of tropical deforestation tropical forests are disappearing as the result of many pressures, both local and regional, acting in various combinations in different geographical locations. Bioscience 52(2):143–150

Geist HJ, Lambin EF (2004) Dynamic causal patterns of desertification. Bioscience 54:817–829

Geri F, Amici V, Rocchini D (2010) Human activity impact on the heterogeneity of a Mediterranean landscape. Appl Geogr 30:370–379

Hennig EI, Schwick C, Soukup T, Orlitová E, Kienast F, Jaeger JA (2015) Multi-scale analysis of urban sprawl in Europe: Towards a European de-sprawling strategy. Land Use Policy 49:483–498

Houet T, Verburg PH, Loveland TR (2010) Monitoring and modeling landscape dynamics. Landsc Ecol 25(2):163–167

Istat (2006) Atlante Statistico dei Comuni. Versione 1.0 del 19/07/2006. Progetto interdipartimentale «Informazione statistica territoriale e settoriale per le politiche strutturali 2001–2008». Roma. Accessed January 2016. http://www.istat.it/dati/catalogo/20061102_00/.

Jansen LJM, Di Gregorio A (2004) Land cover classification system: basic concepts, main software functions and overview of the “land system” approach. In: Groom G (ed) Developments in strategic landscape monitoring for the Nordic countries. Nordic Council of Ministers of Environment, Copenhagen. ANP 2004/705:64–73

Jomaa I, Auda Y, Abi Saleh B, Hamzé M, Safi S (2008) Landscape spatial dynamics over 38 years under natural and anthropogenic pressures in Mount Lebanon. Landsc Urban Plan 87:67–75

Kasanko M, Barredo JI, Lavalle C, McCormick N, Demicheli L, Sagris V, Brezger A (2006) Are European cities becoming dispersed?: a comparative analysis of 15 European urban areas. Landsc Urban Plan 77(1):111–130

Keesstra SD, Bouma J, Wallinga J, Tittonell P, Smith P, Cerdà A, Montanarella L, Quinton JN, Pachepsky Y, van der Putten WH, Bardgett RD, Moolenaar S, Mol G, Jansen B, Fresco LO (2016) The significance of soils and soil science towards realization of the United nations sustainable development goals. Soil 2:111–128

Kroll F, Müller F, Haase D, Fohrer N (2012) Rural–urban gradient analysis of ecosystem services supply and demand dynamics. Land Use Policy 29(3):521–535

Kroonenberg PM (2008) Applied multiway data analysis. Wiley, London

La Greca P, Barbarossa L, Ignaccolo M, Inturri G, Martinico F (2011) The density dilemma. A proposal for introducing smart growth principles in a sprawling settlement within Catania Metropolitan Area. Cities 28(6):527–535

Larondelle N, Haase D (2013) Urban ecosystem services assessment along a rural–urban gradient: a cross-analysis of European cities. Ecol Indic 29:179–190

Loveland TR, Estes JE, Scepan J (1999) Introduction: special issue on global land cover mapping and validation. Photogramm Eng Remote Sens 65(9):1011–1012

Loveland TR, Sohl TL, Stehman SV, Gallant AL, Sayler KL, Napton DE (2002) A strategy for estimating the rates of recent United States land-cover changes. Photogramm Eng Rem Sens 68:1091–1099

Malavasi M, Carboni M, Cutini M, Carranza ML, Acosta AT (2014) Landscape fragmentation, land-use legacy and propagule pressure promote plant invasion on coastal dunes: a patch-based approach. Landsc Ecol 29(9):1541–1550

Malavasi M, Santoro R, Cutini M, Acosta ATR, Carranza ML (2013) What has happened to coastal dunes in the last half century? A multitemporal coastal landscape analysis in Central Italy. Landsc Urban Plan 119:54–63

Marchetti M, Vizzarri M, Lasserre B, Sallustio L, Tavone A (2015) Natural capital and bioeconomy: challenges and opportunities for forestry. Ann Silvic Res 38(2):62–73

Martinez-Fernandez J, Ruiz-Benito P, Zavala MA (2015) Recent land cover changes in Spain across biogeographical regions and protection levels: Implications for conservation policies. Land Use Policy 44:62–75

Mol G, Keesstra SD (2012) Editorial: soil science in a changing world. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 4:473–477

Parras-Alcántara L, Lozano-García B, Keesstra S, Cerdà A, Brevik EC (2016) Long-term effects of soil management on ecosystem services and soil loss estimation in olive grove top soils. Sci Total Environ 571:498–506

Paul V, Tonts M (2005) Containing urban sprawl: trends in land use and spatial planning in the metropolitan region of Barcelona. J Environ Plan Manage 48:7–35

Pellegrini G (2002) Proximity, polarization and local labor market performances. Netw Sp Econ 2:151–174

Pelorosso R, Leone A, Boccia L (2009) Land cover and land use change in the Italian central Apennines: a comparison of assessment methods. Appl Geogr 29:35–48

Petit CC, Lambin EF (2002) Long-term land-cover changes in the Belgian Ardennes (1775–1929): model-based reconstruction vs. historical maps. Glob Change Biol 8:616–630

Prados MJ (2005) Territorial recognition and control of changes in dynamic rural areas: analysis of the naturbanization process in Andalusia, Spain. J Environ Plan Manage 48(1):65–83

Quatrini V, Barbati A, Carbone F, Giuliarelli D, Russo D, Corona P (2015) Monitoring land take by point sampling: pace and dynamics of urban expansion in the Metropolitan City of Rome. Landsc Urban Plan 143:126–13

Rodrigo Comino JT, Iserloh T, Lassu A, Cerdà SD, Keesstra M, Prosdocimi C, Brings C, Marzen M, Ramos MC, Senciales JM, Ruiz Sinoga JD, Seeger M, Ries JB (2016) Quantitative comparison of initial soil erosion processes and runoff generation in Spanish and German vineyards. Sci Total Environ 565:1165–1174

Romano B, Zullo F (2014) The urban transformation of Italy’s Adriatic coastal strip: fifty years of unsustainability. Land Use Policy 38:26–36

Romero-Díaz A, Ruiz-Sinoga JD, Robledano-Aymerich F, Brevik EC, Cerdà A (2017) Ecosystem responses to land abandonment in Western mediterranean mountains. Catena 14:824–835

Sallustio L, Quatrini V, Geneletti D, Corona P, Marchetti M (2015) Assessing land take by urban development and its impact on carbon storage: Findings from two case studies in Italy. Environ Impact Asses 54:80–90

Salvati L, Carlucci M (2011) The economic and environmental performances of rural districts in Italy: are competitiveness and sustainability compatible targets? Ecol Econ 70(12):2446–2453

Salvati L, Colantoni A (2015) Land use dynamics and soil quality in agro-forest systems: a country-scale assessment in Italy. J Environ Plann Manage 58(1):175–188

Salvati L, Ferrara A (2015) Profiling agro-forest landscape types at the wildland–urban interface: an exploratory analysis. Agrofor Syst 89(2):291–303

Salvati L, Tombolini I, Perini L, Ferrara A (2013) Landscape changes and environmental quality: the evolution of land vulnerability and potential resilience to degradation in Italy. Reg Environ Change 13(6):1223–1233

Salvati L, Tombolini I, Gemmiti R, Carlucci M, Bajocco S, Perini L, Ferrara A, Colantoni A (2017) Complexity in action: untangling latent relationships between land quality, economic structures and socio-spatial patterns in Italy. PLoS One 12(6):e0177853

Salvati L, Zitti M (2012) Monitoring land use quality and its management in a mediterranean Urban Region. Appl Geogr 32(2):896–903

Saurì D, Breton F (1998) The Mediterranean. Socio-economic and environmental driving forces. Environ Technol Cult 21:15–25

Schlacher TA, Jones AR, Dugan JE, Weston MA, Harris LL, Schoeman DS, Hubbard D, Scapini F, Nel R, Lastra M, McLachlan A, Peterson CH (2014) Open-coast sandy beaches and coastal dunes. Chapters 1–2. In: Lockwood JL, Maslo B (eds) Coastal conservation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 37–94

Schlacher TA, Schoeman DS, Dugan J, Lastra M, Jones A, Scapini F, McLachlan A (2008) Sandy beach ecosystems: Key features, management challenges, climate change impacts, and sampling issues. Marine Ecol 29:70–90

Serra P, Pons X, Sauri D (2008) Land-cover and land-use change in a mediterranean landscape: a spatial analysis of driving forces integrating biophysical and human factors. Appl Geogr 28:189–209

Serra P, Vera A, Tulla AF, Salvati L (2014) Beyond urban–rural dichotomy: exploring socioeconomic and land-use processes of change in Spain (1991–2011). Appl Geogr 55:71–81

Shrestha MK, York AM, Boone CG, Zhang S (2012) Land fragmentation due to rapid urbanization in the Phoenix metropolitan area: analyzing the spatiotemporal patterns and drivers. Appl Geogr 32:522–531

Sluiter R, de Jong SM (2007) Spatial patterns of Mediterranean land abandonment and related land cover transitions. Landsc Ecol 22:559–576

Soliman AM (2004) Regional planning scenarios in South Lebanon: the challenge of rural–urban interactions in the era of liberation and globalization. Habitat Int 28:385–408

Stürck J, Levers C, Zanden EH, Schulp CJE, Verkerk PJ, Kuemmerle T, Schrammeijer E (2015) Simulating and delineating future land change trajectories across Europe. Reg Environ Change 15(2):1–17

Tasser E, Walde J, Tappeiner U, Teutsch A, Noggler W (2007) Land-use changes and natural reforestation in the Eastern central Alps. Agric Ecosyst Environ 118(1):115–129

Theobald DM, Romme WH (2007) Expansion of the US wildland–urban interface. Landsc Urban Plan 83(4):340–354

Tomao A, Quatrini V, Corona P, Ferrara A, Lafortezza R, Salvati L (2017) Resilient landscapes in Mediterranean urban areas: understanding factors influencing forest trends. Environ Res 156:1–9

Tomaselli V, Tenerelli P, Sciandrello S (2012) Mapping and quantifying habitat fragmentation in small coastal areas: a case study of three protected wetlands in Apulia (Italy). Environ Monit Assess 184(2):693–713

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Masini, E., Barbati, A., Bencardino, M. et al. Paths to Change: Bio-Economic Factors, Geographical Gradients and the Land-Use Structure of Italy. Environmental Management 61, 116–131 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0950-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0950-0