Abstract

Background

Cosmetic rhinoplasty has been linked to iatrogenic breathing disturbances using clinical tools. However, few studies have evaluated outcomes using validated, patient-centered instruments.

Objective

We aim to determine the incidence and severity of nasal obstruction following cosmetic rhinoplasty as measured by patient-centered, disease-specific instruments.

Design

This is a retrospective review of adult patients who underwent cosmetic rhinoplasty at Stanford Hospital between January 2017 and January 2019. General demographic as well as Nasal Obstruction and Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) and the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) questionnaire data were included. Scores were tracked across postoperative visits and compared to the preoperative state. Patients were subdivided into dorsal hump takedown, correction of the nasal tip, and both.

Results

Of the 68 included patients, 56 were women, and the mean age was 30.6 years. Although mean SCHNOS and NOSE scores increased at the first postoperative interval, mean scores decreased on each subsequent visit. There were no significant increases in SCHNOS or NOSE scores for either dorsal hump takedown, tip correction, or both. There were only two patients who recorded NOSE scores higher than baseline at most recent postoperative visit.

Conclusion

Our results indicate reductive rhinoplasty is not associated with a greater risk of breathing obstruction when performed with modern airway preservation techniques. The initial increases in obstructive symptoms we observed on the first postoperative visit likely represent perioperative swelling given the improvement on follow-up visits. Both the NOSE and SCHNOS are patient-centered questionnaires capable of evaluating nasal obstruction following cosmetic rhinoplasty.

Level of Evidence IV

This journal requires that authors assign a level of evidence to each article. For a full description of these Evidence-Based Medicine ratings, please refer to the Table of Contents or the online Instructions to Authors www.springer.com/00266.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Reductive rhinoplasty reduces nasal size and may compromise the nasal airway. Methods for measuring nasal airway patency following rhinoplasty may be divided into two subgroups: objective and subjective. Numerous objective methods have been described, including acoustic rhinometry, peak nasal inspiratory flowmeter, computed tomography cross-sectional dimensions, and the Glatzel mirror test [1,2,3,4,5,6]. However, these methods are often not feasible in the busy clinic environment. Furthermore, prior work has shown poor correlation between such objective measures and subjective breathing [7, 8]. In addition, whether reduction in nasal size correlates with subjective symptoms has been incompletely explored.

Patient-centered outcomes may represent a more practical and informative option to discern outcomes for the rhinoplasty patient. These data are critical in guiding surgical counseling for patients.

The Nasal Obstruction and Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) and the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) questionnaires are both patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) validated in identifying nasal obstruction (Figs. 1 and 2) [9, 10]. With this study, we aim to determine whether cosmetic rhinoplasty worsens nasal obstruction as measured by NOSE and SCHNOS scores. While prior studies have examined patients using the NOSE score, this instrument was never validated for rhinoplasty patients [11, 12]. The present study represents the first such analysis using the validated SCHNOS prom in patients undergoing reductive rhinoplasty.

Methods

This retrospective review was performed at Stanford University following approval by the Stanford Institutional Review Board. Chart review of those patients treated by a single surgeon (S.P.M.) between January 1, 2017, and January 1, 2019, was performed. Inclusion criteria were completion of cosmetic rhinoplasty, the absence of trauma or additional nasal surgery within one year of the procedure, and a minimum of at least one postoperative follow-up in clinic. We did not include patients who underwent both cosmetic rhinoplasty and functional rhinoplasty. However, three patients did have septoplasties to obtain cartilage grafts for the repair.

We divided patients into subsets based on the performed procedure. The three subgroups were dorsal hump takedown (Joseph method), tip correction, and both. With this distinction, we aimed to determine whether either dorsal hump reduction or tip correction was more hazardous for the development of nasal obstruction. All hump reductions patients underwent midvault repair using autospreader flaps or traditional spreader flaps. All tip reduction procedures were characterized by preservation of at least 7 mm of the lateral crus, use of lateral crural struts, or cephalic hinged flaps as previously described for stabilization of the ala/lateral nasal wall complex [13]. Ultimately, sixty-eight patients met the inclusion criteria for this study.

The Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness (NOSE) scale and the Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) questionnaires were both collected pre- and postoperatively. Both NOSE and SCHNOS scores were summed to provide total obstructive symptom scores. We analyzed differences between preoperative and all postoperative scores. Intervals for postoperative evaluation were 1–2 months, 2–5 months, 5–8 months, and 8–12 months. These are postoperative follow-up intervals the senior surgeon schedules for rhinoplasty patients.

Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness (NOSE) instrument

The Nasal Obstruction Septoplasty Effectiveness (NOSE) is a 5-item, disease-specific patient-reported outcome measure of nasal obstruction [9]. This is the most widely used and accepted PROM to assess nasal obstruction in rhinoplasty, although it was never validated for this procedure. Elements are scored from 0 to 4, or “Not a problem” to “Severe problem” (Fig. 1). Scores are summed and multiplied by 5 to allow a minimum score of 0 and a maximum score of 100. Higher scores correlate with severity of nasal obstruction. A study by Lipan et al. previously established that a score of 30 best differentiated patients with and without nasal obstruction [11]. NOSE scores higher than 30 were considered symptomatic nasal obstruction for the purposes of this study.

Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) instrument

The Standardized Cosmesis and Health Nasal Outcomes Survey (SCHNOS) is a 10-item, disease-specific patient-reported outcome measure for functional and cosmetic rhinoplasty [10]. The first four elements pertain to the nasal obstruction domain, and these were evaluated and analyzed in the present study. The remaining six elements evaluate patient perception of the nasal aesthetic domain. Elements are scored from 0 to 5, or “No problem” to “Extreme problem,” for a maximum score of 50. We only included those elements pertaining to nasal obstruction, or the first four questions, for this study (Fig. 2). Items were summed and then multiplied by 5 to achieve a total score. Hence, the maximum SCHNOS obstructive (SCHNOS-O) score is 100.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and descriptive statistics of the data were performed to evaluate mean, standard deviation, range, and frequency. SCHNOS-O and NOSE scores were calculated based on the above formulae for the analysis. Data were analyzed for statistical differences using Wilcoxon’s test or paired t test. Analysis was aided with computational statistics. A p value less than 0.05 was considered significant (Table 1).

Results

The charts of 272 patients who underwent rhinoplasty during the specified time frame were assessed, and ultimately 68 met the inclusion criteria. Of the 68 patients, 56 were female. Mean age was 30.57 years, and range was 18–58. Twelve of the patients had previously undergone rhinoplasty. 14.7% requested dorsal hump takedown alone (n = 10), 20.6% requested tip only correction (n = 14), and 64.7% requested both dorsal hump takedown and tip correction (n = 44). Mean follow-up was 147 days.

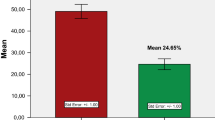

Preoperative mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores were 17.3 and 18.6, respectively (Fig. 3). At first postoperative visit (within 1–2 months of operative date), mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores were 22.3 and 27.7 (n = 60, two-tailed p = 0.0554 and 0.0031), respectively. At the 2–5-month postoperative interval, mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores were 18.9 and 21.0 (n = 24, two-tailed p = 0.4204 and 0.1391), respectively. At the 5–8-month interval, mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores were 11.1 and 11.8 (n = 19, two-tailed p = 0.8278 and 1.000), respectively. At the 8–12-month interval, mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores were 9 and 10.3 (n = 15, two-tailed p = 0.3982 and 0.4844), respectively.

In total, seventeen patients presented for cosmetic rhinoplasty with baseline nasal obstruction (Fig. 4). In this subgroup, mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores decreased significantly from 49.4 to 20.3 (95% confidence interval = 18.91, 39.33; p < 0.0001) and 52.6 to 26.7, p (95% confidence interval = 16.74, 35.03; p < 0.0001) at most recent clinic visit, and sixteen of these patients ultimately reported improved scores from baseline. Eleven of the seventeen patients achieved improvements in NOSE scores greater than the minimal clinically important difference (MCID, > 24.4 points) as previously described [14]. Seven of the patients achieved improvements in SCHNOS-O scores greater than the minimal clinically important difference (> 28 points). Only one patient had a mild worsening of scores (NOSE 35 to 40, SCHNOS-O 50 to 60) on first postoperative visit. This patient did not return for subsequent follow-up.

Tip Correction

Mean preoperative NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores for isolated tip correction patients were 15 and 11.1, respectively (n = 14). Mean scores at first postoperative visit (1–2 months postoperatively) were 11.5 and 18.1 (n = 13). Mean scores increased to 26.7 and 25 at the 2–5-month interval (n = 3), but decreased to 8.1 and 6.9 at the 5–8-month interval (n = 8). At the 8–12-month interval, scores decreased further to 5 and 6.7 (n = 3). These changes were not found to be statistically significant.

Three patients who presented for tip correction complained of nasal obstruction at their preoperative visit (NOSE scores > 30). Each of these patients demonstrated improvement in NOSE scores from pre- to postoperatively (mean NOSE preoperatively 38.33 and mean on most recent evaluation 5).

Dorsal Hump Takedown

Mean preoperative NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores for dorsal hump takedown patients were 15 and 17.5, respectively (n = 10). Mean scores at first postoperative visit were 15.5 and 18.5 (n = 10). One patient followed up both during the 2–5-month interval and the 5–8-month interval. SCHNOS-O and NOSE scores had decreased to 0 at both visits. These changes were not found to be statistically significant.

Two patients who presented for dorsal hump takedown complained of nasal obstruction at their preoperative visit. Both demonstrated improvement in NOSE scores at first postoperative visit, but did not return for follow-up. One patient presented with a NOSE score of 5, and on first postoperative visit, the NOSE score was 30. This patient did not follow up for further evaluation.

Dorsal Hump Takedown and Tip Correction

Mean preoperative SCHNOS-O and NOSE scores for combined dorsal hump takedown and tip correction patients were 18.5 and 21.3, respectively (n = 44). Mean scores at first postoperative visit increased to 27.8 and 33.5 (n = 37, two-tailed p value = 0.01273 and 0.0131). Mean scores returned to baseline at the 2–5-month interval, with scores of 18.5 and 21.5 (n = 20, two-tailed p value = 0.936 and 0.9192) and further to 14.5 and 17 at the 5–8-month interval (n = 10, two-tailed p = 0.5417 and 0.4519). Eleven patients returned to clinic at the 8–12-month interval, and mean scores were 8.6 and 11.4 (n = 11, two-tailed p value = 0.2578 and 0.3675).

Twelve combined functional and cosmetic patients presented preoperatively with nasal obstruction per NOSE scores (mean 52.92, SD 15.14). Eleven of these patients had improvements in NOSE scores by their most recent follow-up visit, and the twelfth had mild worsening of scores (mean 20, SD 17.71, two-tailed p value = 0.0003).

Discussion

Prior studies have disagreed regarding risk to nasal function following rhinoplasty. A study by Grymer et al. used acoustic rhinometry to measure internal nasal valve narrowing by 22% following cosmetic rhinoplasty and by 11% at the pyriform aperture following lateral osteotomies, suggesting nasal airway compromise [15]. A prior study by the senior author examined the efficacy of autospreader flaps in preventing airway compromise in dorsal hump takedown patients [12].

Conversely, Zoumalan et al. demonstrated both subjective and objective improvements in nasal patency in 31 patients following septorhinoplasty [16]. These findings were reproduced by Erdogen et al. for 40 septorhinoplasty patients [17]. However, these studies evaluated the combined cosmetic and functional rhinoplasty patient, and procedures such as spreader and alar batten grafts, turbinate reduction, or septoplasty were performed concomitantly. In our study, we did not include patients who underwent procedures to improve nasal patency. In addition, these studies measured subjective outcomes with visual analog scales, rather than disease-specific and validated patient-reported outcome measures, such as the NOSE or SCHNOS.

Celebi et al. evaluated objective and subjective measurements of nasal patency in 50 reduction rhinoplasty patients, noting no reduction in nasal patency [3]. Again, only a visual analog scale was used to measure symptoms. In addition, no distinction was made between tip rhinoplasty and dorsal hump takedown.

We have demonstrated cosmetic rhinoplasty does not compromise patient perception of nasal patency. Rather, our results demonstrated mean NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores decreased following cosmetic rhinoplasty. Although there was a statistically significant increase in NOSE scores on first postoperative visit, mean NOSE and SCHNOS scores decreased at all subsequent visits. We suspect the initial increase in obstructive scores is due to perioperative swelling, which resolves on subsequent visits. We found no relationship between tip correction or dorsal hump takedown and nasal obstruction.

Of particular note, sixteen of seventeen patients with baseline nasal obstruction who presented for cosmetic rhinoplasty demonstrated improved NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores at most recent clinic visit. Furthermore, 64.7% and 41.1% achieved improvements in NOSE and SCHNOS-O scores greater than the MCID. This suggests isolated cosmetic rhinoplasty provided a clinically significant functional benefit for these patients. Whether cosmetic rhinoplasty offered structural support for the nasal airway, or if some component of nasal function is linked to patient appearance, remains unclear. Importantly, we routinely employ methods to reduce the risk of nasal airway compromise in our patients undergoing tip reduction and/or dorsal reduction, such as spreader grafts or autospreader flaps, as described previously [12].

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to demonstrate neither isolated tip correction nor dorsal hump takedown compromises nasal function using disease-specific, patient-reported outcome measures. Of the 68 patients included, only two patients registered worsened NOSE scores on most recent postoperative evaluation. One of these patients did not follow up past the first postoperative visit, so this result may indicate perioperative swelling rather than structural pathology as previously mentioned.

It is important to note there are several limitations to this study. Chiefly, this is a retrospective chart review and therefore bears the weaknesses inherent to such a study design. Our data are incomplete, and we lack follow-up data for each patient at every postoperative interval. Numerous patients failed to follow up past the first postoperative visit, which limits our ability to assess long-term outcomes and may distort overall NOSE and SCHNOS scores. Furthermore, there may be a bias toward return patients having more concerns than those who fail to follow up. However, this would presumably skew the data toward worsening obstruction.

We did not obtain objective measurements of nasal airflow, although a review by Ottaviano et al. found peak nasal inspiratory flow, acoustic rhinometry, and rhinomanometry capable tools [18]. However, a study by Lam et al. found subjective and objective measures of nasal obstruction to correlate poorly, and thus, we focused only on patient-reported outcomes for this study [8].

Finally, our tip correction and dorsal hump takedown subgroups were relatively small, which impaired our ability to find statistical differences between intervals despite the suggested trends. Further studies may incorporate multiple surgeons/centers and longer-term follow-up.

Conclusion

Herein, we have used validated PROMs to study the natural history of nasal obstruction following aesthetic rhinoplasty. To our knowledge, this is the first such study using the relatively new but highly validated SCHNOS measure, in addition to the NOSE questionnaire. Our results indicate when cosmetic rhinoplasty is performed with proper midvault reconstruction techniques, the risk of breathing obstruction is low. Future studies may be aimed at comparison of the Joseph hump takedown method with the Cottle, or dorsal preservation method.

References

Grymer LF (1995) Reduction rhinoplasty and nasal patency: change in the cross-sectional area of the nose evaluated by acoustic rhinometry. Laryngoscope 105:429–431

Edizer DT, Erisir F, Alimoglu Y, Gokce S (2012) Nasal obstruction following septorhinoplasty: how well does acoustic rhinometry work? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 270:609–613

Celebi S, Caglar E, Yilmaz E et al (2014) Does rhinoplasty reduce nasal patency? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 123(10):701–704

Bloom JD, Sridharan SS, Hagiwara M et al (2012) Reformatted computed tomography to assess the internal nasal valve and association with physical examination. Arch Fac Plast Surg 14(5):331–335

Moche JA, Cohen JC, Pearlman SJ et al (2013) Axial computed tomography evaluation of the internal nasal valve correlates with clinical valve narrowing and patient complaint. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 3(7):592–597

de Pochat VD, Alonso N, Mendes RR et al (2012) Assessment of nasal patency after rhinoplasty through the Glatzel mirror. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 16(3):341–345

Andres RF, Vuyk HD, Ahmed A et el. Correlation between subjective and objective evaluation of the nasal airway. A systematic review of the highest level of evidence. Clin Otolaryngol. 2009, 34(6):518–25

Lam DJ, James KT, Weaver EM (2006) Comparison of anatomic, physiological, and subjective measures of the nasal airway. Am J Rhinol 20(5):463–470

Stewart MG, Witsell DL, Smith TL et al (2004) Development and validation of the nasal obstruction symptom evaluation (NOSE) scale. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 130(2):157–163

Moubayed SP, Ioannidis JP, Saltychev M, Most SP (2018) The 10-item standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey (SCHNOS) for functional and cosmetic rhinoplasty. JAMA Fac Plast Surg 20(1):37–42

Lipan MJ, Most SP (2013) Development of a severity classification system for subjective nasal obstruction. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 15(5):358–361

Yoo S, Most SP (2011) Nasal airway preservation using the autospreader technique: analysis of outcomes using a disease-specific quality-of-life instrument. Arch Fac Plast Surg 13(4):231–233

Murakami CS, Barrera JE, Most SP (2009) Preserving structural integrity of the alar cartilage in aesthetic rhinoplasty using a cephalic turn-in flap. Arch Fac Plast Surg 11(2):126–128

Kandathil CK, Saltychev M, Abdelwahab M, Spataro EA, Moubayed SP, Most SP. Minimal clinically important difference of the standardized cosmesis and health nasal outcomes survey. Aesthet Surg J. sjz070, https://doi-org.laneproxy.stanford.edu/10.1093/asj/sjz070.

Grymer LF, Gregers-Petersen C, Baymler Pedersen H (1999) Influence of lateral osteotomies in the dimensions of the nasal cavity. Laryngoscope 109:936–938

Zoumalan RA, Constantinides M (2012) Subjective and objective improvement in breathing after rhinoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg 14:423–428

Erdogan M, Cingi C, Seren E (2012) Evaluation of nasal airway alterations associated with septorhinoplasty by both objective and subjective methods. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 270:99–106

Ottaviano G, Fokkens WJ (2016) Measurements of nasal airflow and patency: a critical review with emphasis on the use of peak nasal inspiratory flow in daily practice. Allergy 71:162–174

Funding

No funding was obtained for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okland, T.S., Kandathil, C., Sanan, A. et al. Analysis of Nasal Obstruction Patterns Following Reductive Rhinoplasty. Aesth Plast Surg 44, 122–128 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-019-01484-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-019-01484-5