Abstract

Purpose

Peri-acetabular osteotomy, especially curved peri-acetabular osteotomy, is an effective surgical procedure for re-orientating the acetabulum. However, there have been few reports on this procedure in teenagers. The purpose of this study was to investigate the treatment outcomes of curved peri-acetabular osteotomy in teenagers.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 33 hips in 27 teenage patients with acetabular dysplasia who underwent curved peri-acetabular osteotomy between 1995 and 2012. The mean age was 17.0 years (range, 14–19 years). The mean follow-up duration at the most recent physical examination was 33.3 months (range, 24–96 months). All hips were evaluated in terms of the Harris hip score, radiographic measurements, and complications.

Results

The mean Harris hip score improved from 80.1 points pre-operatively to 95.4 points post-operatively (p < 0.001). There were significant differences in all of the radiographic measurements between the pre-operative and post-operative values (p < 0.001). One major complication occurred (symptomatic ischial nonunion) and required subsequent surgery. Nine hips had minor complications, including nonunion of the superior ramus osteotomy (four hips), superficial stitch abscess (two hips), and transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy (three hips).

Conclusions

Satisfactory results can be obtained clinically and radiographically after curved peri-acetabular osteotomy in adolescents. Osteotomy for acetabular dysplasia is effective in teenagers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Numerous reports have implicated acetabular dysplasia as an etiologic factor in the development of osteoarthritis of the hip joint in Europe and North America [1, 2]. In Japan, almost 80 % of cases of osteoarthritis of the hip joint are secondary to congenital dislocation or dysplasia of the hip.

Although peri-acetabular osteotomy provides excellent radiographic and clinical results in adults, there are no clinical and radiographic results for curved peri-acetabular osteotomy (CPO) in the treatment of developmental dysplasia of the hip in teenagers. It can be hypothesized that patients who present with symptoms at an earlier time, e.g. during the adolescent period, have more severe dysplasia and have more often undergone previous surgery than patients who present at a later time as adults with mild hip dysplasia.

The purpose of the present study was to report the clinical outcomes and complications associated with CPO for hip dysplasia in teenagers.

Materials and methods

Since 1995, we have performed peri-acetabular osteotomy for the treatment of symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in teenagers and adults [3]. For our procedure, a direct anterior approach was used for surgical exposure, and no exposure of the outer table of the pelvis was required (as in the modified Ganz procedure) [4]. A spherical osteotomy of the acetabulum (modified rotational acetabular osteotomy) was created for CPO [5].

We prospectively reviewed 474 symptomatic hips that underwent CPO from August 1995 to December 2012. In this series, we excluded 22 hips with Legg–Calvé–Perthes disease. Moreover, we excluded 319 patients who were aged above 20 years. Finally, we retrospectively reviewed 33 hips in 27 adolescent female patients treated by CPO. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. All patients provided informed consent before participation in the study.

All patients presented with symptoms of hip dysplasia for at least five months, and had intact joint congruency on an anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the hip at maximum abduction. In all cases, the epiphyseal line of the Y cartilage was closed. Patients were excluded from the study if they were not observed for at least two years after surgery. Clinical evaluations were performed using the Harris hip score. Additionally, radiographic evaluations on an AP radiograph of the pelvis and a false-profile view of the affected hip were performed by two authors.

Dysplasia was quantified by the lateral centre-edge (CE) angle of Wiberg (normal, >20°) [6], Sharp angle (normal, <45°) described by Sharp [7], ventral CE angle (normal, >25°) described by Lequesne and de Seze [8], acetabular index of weightbearing zone (normal, <10°), and femoral head extrusion index (normal, >70°) described by Heyman and Herndon [9].

The severity of the secondary osteoarthrosis before CPO was graded using the Tönnis classification system [10]. Specifically, hips with subchondral sclerosis were classified as grade 1, hips with subchondral cyst formation and partial cartilage interval narrowing were classified as grade 2, hips with severe or complete but localized cartilage interval narrowing were classified as grade 3, and hips with extensive and severe complete cartilage interval loss were classified as grade 4.

Indications for CPO included acetabular dysplasia with symptoms for more than five months, lateral CE angle of <16° on AP radiographs, and improvement of joint congruency on an AP radiograph in the abducted position [3, 11, 12]. CPO was not recommended for patients with aggravation of joint congruency in the abducted position. Patients who had undergone previous surgery were excluded from the study.

All surgical procedures were performed by two senior authors. The radiographic measurements were made three times on different occasions by three authors who were blinded to the clinical results, and the mean values were calculated. The measurements were then analysed for intra-observer and inter-observer reliability. The intraclass correlation coefficients of these measurements were 0.95–0.99 for intra-observer variance and 0.96–0.98 for inter-observer variance.

Surgical technique

The osteotomy was carried out through an anterior approach as previously described [3]. A dual anterior approach for this procedure has recently been recommended [4]. The gluteus muscles were not stripped from the iliac bone, thereby preserving the blood supply to the acetabular fragment and enabling smooth re-orientation because the osteotomy surfaces had the same curvatures. The skin incision was approximately 10 cm in length. After osteotomy of the anterior superior iliac spine, it was retracted medially with the sartorius muscle attached. The iliacus muscle was detached and a C-shaped osteotomy line was marked from the anterior inferior iliac spine to the distal part of the quadrilateral surface. An osteotomy of the quadrilateral surface was carried out using a curved osteotome, and the ischium, superior pubic ramus, and ilium were then divided. The acetabular fragment was reoriented anteriorly and laterally and fixed with two or three screws. An image intensifier or intra-operative radiography was used to ensure that the desired goals were achieved, namely, that the femoral head was adequately covered by the re-oriented acetabular fragment and that lateral excess was not present. The range of movement in the hip joint was then assessed. When flexion was limited, the anterior reorientation of the acetabular fragment was reduced to avoid femoro-acetabular impingement.

Active motion exercises were initiated on the first post-operative day. Partial weight-bearing (10 kg) using two crutches or a walker was allowed on the third post-operative day, and full weight-bearing was allowed after eight weeks post-operatively.

Statistical analysis

The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the clinical results and radiographic measurements between the pre-operative and post-operative values. Values of p < 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

The mean age of the patients at surgery was 17.0 years (range, 14–19 years), and the mean follow-up period was 33.3 months (range, 24–96 months). The mean body mass index was 21.7 kg/m² (range, 18.0–23.5 kg/m²). The mean surgical time for CPO was 96.4 minutes (range, 65–140 min). The mean Harris hip score improved from 80.1 points (range, 45–90 points) pre-operatively to 95.4 points (range, 85–100 points) post-operatively. In this case series, there was one patient with Down syndrome.

No hips underwent concomitant open osteochondroplasty (plasty of the femoral head–neck offset) through the same surgical approach to evaluate and address the intra-articular pathology.

Radiographic results

Radiographic results are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 shows the radiographic dysplasia parameters. Table 2 shows the severity of the secondary osteoarthrosis graded using the Tönnis classification system. Significant radiographic improvement from the pre-operative values to the two-year follow-up evaluations was seen for all hip dysplasia parameters (Table 1). One hip worsened from grade 0 to 1; however, the other hips showed no change from before to after the operation (Table 2).

Major complications

One hip exhibited mild symptomatic ischial nonunion that required subsequent surgery. There were no another obvious major complications such as arterial bleeding, embolization, motor nerve palsy, deep infection, necrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum, reflex sympathetic dystrophy, and delayed union or nonunion of the ilium (Table 3).

Minor complications

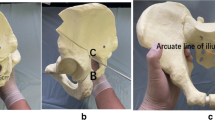

The most common minor complication was nonunion at an osteotomy site. Four hips (12 %) had nonunion of the superior pubic ramus (Fig. 1). All of these patients were completely asymptomatic.

Other minor complications included superficial stitch abscess in one hip (3 %), transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve numbness in three hips (9 %), and stress fracture of the inferior pubic ramus found incidentally on a routine follow-up examination in two patients (6 %). All of these complications were asymptomatic and did not require further intervention.

Two hips had two minor complications each. Thus, nine hips (27 %) presented with complications or symptoms, while 24 hips (73 %) had no post-operative clinical or radiographic issues (Table 3).

Subsequent surgery

Overall, 27 hips required subsequent surgical procedures, which included removal of asymptomatic screws in 33 hips (82 %). All of these procedures involved removal of the anterior superior iliac spine screw at a mean time of 24 months post-operatively.

Two patients had various subsequent procedures. As noted above, one patient underwent subsequent surgery because of ischial nonunion. Briefly, because the nonunion continued to present mild symptoms, autologous bone-grafting and plate fixation of the nonunion were performed at 15 months after the index procedure, with complete resolution of symptoms. The other patient had a labral tear as shown by pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging. A labral suture under arthroscopic surgery was performed for this patient 11 months after CPO because the symptom remained after CPO and labral damage was observed in the hip joint during arthroscopy.

Discussion

Peri-acetabular osteotomy has become one of the most successful procedures for treating hip dysplasia in adults and adolescents. However, reports on its ability to successfully treat hip dysplasia in younger patients are limited [13].

In CPO, the curvilinear C-shaped osteotomy makes it easy to move and reposition the acetabular fragment and does not result in a large gap at the osteotomy surface [3, 12]. Furthermore, it is not necessary to expose the joint capsule by detaching the gluteus minimus and rectus femoris muscles, so no incisions are made outside of the pelvis.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to describe the complications associated with CPO in teenage patients. Our study focused on the prevalence and types of complications as well as the risk factors for the development of these complications in teenage patients. In the present study, we have reported on 33 hips with dysplasia in 27 patients with a mean age of 17.0 years.

Patients who present with pain for the first time as adults are more likely to have less severe dysplasia than patients who present at a younger age with severe dysplasia and have often undergone previous surgery to treat their dysplasia. It can be hypothesized that the severity of the hip dysplasia makes the treatment of such teenage patients challenging, especially compared with adult patients.

Thawrani et al. [13] described 83 patients with an average age of 15.6 years who had an average pre-operative lateral CE angle of −0.14°, indicating severe acetabular deformity. The teenage patients in the present study had an average pre-operative lateral CE angle of 10.2°. Naito et al. [3] reported that 128 adult hips with dysplasia that underwent CPO had an average pre-operative lateral CE angle of 4.0°. Thus, the results of this series do not confirm the hypothesis that patients who present with pain for the first time as adults are more likely to have less severe dysplasia than patients who present at a younger age. Maeyama et al. [14] suggested that hip instability increases in proportion to the degree of dysplasia and that the CE angle is the most useful factor for predicting instability of the hip joint. They also reported that improvement in dysplasia regained stability and decreased the possibility of cartilage damage. For these reasons, teenage patients with acetabular dysplasia who have symptoms for more than five months should be considered candidates for surgery before cartilage damage occurs.

Clohisy et al. [15] reported on a series of 16 patients who underwent Bernese peri-acetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia at a mean age of 17.6 years. Overall, they reported a 10 % rate of complications, including excessive bleeding in two patients, reflex sympathetic dystrophy in two patients, and sciatic nerve palsy with residual deficit, deep vein thrombosis, and nonunion requiring revision surgery in one patient each. Ganz et al. [4] reported femoral nerve palsy as a major complication in their series. Major nerve injury has been reported to occur in 1–10 % of patients in the literature [1–3, 5, 6, 13, 15–24].

In previous reports, serious complications, such as motor nerve palsy [18, 19], deep infection [18], necrosis of the femoral head or acetabulum [19, 21], and delayed union or nonunion of the ilium [21–24], were observed. However, no such major complications occurred in our series.

Thawrani et al. [13] reviewed 83 adolescent patients who underwent Bernese peri-acetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia. They reported three major complications, including excessive arterial bleeding requiring embolisation, osteonecrosis of the acetabular fragment, and osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Overall, 18 hips (22 %) had minor complications, including nonunion of the superior pubic ramus osteotomy (five hips), superficial stitch abscess (four hips), and transient lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy (four hips). The frequencies of these minor complications were substantially similar to those in the present study.

Stress fractures are thought to arise when the load transmission only occurs through the inferior limb of the pubis and ischium [24]. Fractures of the inferior limb of the pubis were identified in three hips (9 %) among all hips. Although the patients with stress fractures had complaints of pain in the buttocks or groin, the progression was denoted as a general pubic bone fracture. After resting, all hips with a fracture of the inferior limb of the pubis showed union, and the pain had disappeared without special treatment by the most recent follow-up.

To prevent nonunion, we have used various devices. Since 2005, we have performed pubic osteotomies using an inclination of 30° to the horizontal line [25]. The advantages of this method are not only medialisation of the femoral head and easy rotation of the acetabular fragment, but also the possibility of preventing nonunion because the osteotomy site has a large contact area. Moreover, since 2012, we have also performed a tipping technique and carried out decortication at the superior limb of the pubis to promote union. In five cases that underwent this technique, nonunion of the superior limb of the pubis did not occur.

We acknowledge several limitations to this study. First, the study population was small. However, this was attributable to the strict inclusion criteria. Second, we cannot predict the long-term failure rate because the follow-up period was relatively short and not uniform for all patients. Third, we used the Harris hip score for evaluation of the clinical outcomes, instead of the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) activity score, which is a patient-based outcome especially focused on functional aspects [26]. The reason why we could not use the UCLA activity score is that our series included cases from 1992, and we were unable to obtain pre-operative values for the UCLA activity score in these cases. However, we think that we can obtain sufficient results from the Harris hip score.

The goals of hip preservation surgery in young patients using curved peri-acetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia are to improve pain, restore normal function, and ultimately improve the natural history of the hip to avoid or limit total hip arthroplasty.

In conclusion, CPO is a joint-preserving procedure that very effectively corrects acetabular dysplasia in teenage patients and has a low rate of major complications.

References

Jacobsen S, Sonne-Holm S, Soballe K, Gebuhr P, Lund B (2005) Joint space width in dysplasia of the hip: a case–control study of 81 adults followed for ten years. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 87:471–477

Wedge JH, Wasylenko MJ (1979) The natural history of congenital disease of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 61-B:334–338

Naito M, Shiramizu K, Akiyoshi Y, Ezoe M, Nakamura Y (2005) Curved periacetabular osteotomy for treatment of dysplastic hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 433:129–135

Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW (1988) A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias: technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 418:26–36

Ninomiya S, Tagawa H (1984) Rotational acetabular osteotomy for the dysplastic hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 66:430–436

Massie WK, Howorth MB (1950) Congenital dislocation of the hip. Part I. Method of grading results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 32-A:519–531

Sharp IK (1961) Acetabular dysplasia: the acetabular angle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 43-B:268–272

Lequesne M, de Seze (1961) False profile of the pelvis. A new radiographic incidence for the study of the hip. Its use in dysplasias and different coxopathies. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic 28:643–652 [in French]

Heyman CH, Herndon CH (1950) Legg-Perthes disease; a method for the measurement of the roentgenographic result. J Bone Joint Surg Am 32:767–778

Tonnis D, Heinecke A (1999) Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 81:1747–1770

Murphy S, Deshmukh R (2002) Periacetabular osteotomy: preoperative radiographic predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res 405:168–174

Karashima H, Naito M, Shiramizu K, Kiyama T, Maeyama A (2011) A periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe dysplastic hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469:1436–1441

Thawrani D, Sucato DJ, Podeszwa DA, DeLaRocha A (2010) Complications associated with the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:1707–1714

Maeyama A, Naito M, Moriyama S, Yoshimura I (2009) Periacetabular osteotomy reduces the dynamic instability of dysplastic hips. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 91:1438–1442

Clohisy JC, Barrett SE, Gordon JE, Delgado ED, Schoenecker PL (2005) Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:254–259

Matheney T, Kim YJ, Zurakowski D, Matero C, Millis M (2010) Intermediate to long-term results following the bernese periacetabular osteotomy and predictors of clinical outcome: surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92(Suppl 1 Pt 2):115–129

Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC, Millis MB, Wenger DR (2011) Surgical management of the problematic hip in adolescent and young adult patients. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 19:275–286

Davey JP, Santore RF (1999) Complications of periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 363:33–37

Siebenrock KA, Scholl E, Lottenbach M, Ganz R (1999) Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 363:9–20

Ito H, Matsuno T, Minami A (2007) Rotational acetabular osteotomy through an Ollier lateral U approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res 459:200–206

Biedermann R, Donnan L, Gabriel A, Wachter R, Krismer M, Behensky H (2008) Complications and patient satisfaction after periacetabular pelvic osteotomy. Int Orthop 32:611–617

Hussell JG, Mast JW, Mayo KA, Howie DW, Ganz R (1999) A comparison of different surgical approaches for the periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 363:64–72

Matta JM, Stover MD, Siebenrock K (1999) Periacetabular osteotomy through the Smith-Petersen approach. Clin Orthop Relat Res 363:21–32

Espinosa N, Strassberg J, Belzile EL, Millis MB, Kim YJ (2008) Extraarticular fractures after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 466:1645–1651

Teratani T, Naito M, Kiyama T, Maeyama A (2010) Periacetabular osteotomy in patients fifty years of age or older. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92:31–41

Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, Leunig M (2009) Which is the best activity rating scale for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res 467:958–965

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Hagio and Dr. Muraoka for their helpful suggestions regarding this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sakamoto, T., Naito, M. & Nakamura, Y. Outcome of peri-acetabular osteotomy for hip dysplasia in teenagers. International Orthopaedics (SICOT) 39, 2281–2286 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-015-2973-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-015-2973-6