Abstract

The strength and durability of systemic anti-tumor immune responses induced by cancer vaccines depends on adjuvants to support an immunogenic vaccine site microenvironment (VSME). Adjuvants include water-in-oil emulsions with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) and combinations of toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, including a preparation containing TLR4 and TLR9 agonists with QS-21 (AS15). IFA-containing vaccines can promote immune cell accumulation at the VSME, whereas effects of AS15 are largely unexplored. Therefore, we assessed innate and adaptive immune cell accumulation and gene expression at the VSME after vaccination with AS15 and compared to effects with IFA. We hypothesized that AS15 would promote less accumulation of innate and adaptive immune cells at the VSME than IFA vaccines. In two clinical trials, patients with resected high-risk melanoma received either a multipeptide vaccine with IFA or a recombinant MAGE-A3 protein vaccine with AS15. Vaccine site biopsies were obtained after one or multiple vaccines. T cells accumulated early after vaccines with AS15, but this was not durable or of the same magnitude as vaccination in IFA. Vaccines with AS15 increased durable expression of DC- and T cell-related genes, as well as PD-L1 and IDO1, suggesting complex activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immune function with AS15. These changes were generally greater with vaccines containing IFA, but IFA induced reduction in myeloid suppressor cells markers. Evidence of tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS) formation was observed with both adjuvants. Our findings highlight adjuvant-dependent changes in immune features at the VSME that may impact systemic immune responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

New immune therapies have demonstrated the therapeutic value of harnessing an immune response for cancer treatment. These findings fuel renewed interest in developing effective cancer vaccines. In murine models, cancer vaccines can induce anti-tumor immune responses that mediate durable cancer control. In human clinical trials, cancer vaccines can induce anti-tumor T-cell responses; however, durable clinical responses have been rare [1,2,3]. Cancer vaccines often use purified antigens, which require an effective vaccine adjuvant, yet there is no consensus on the most effective adjuvant strategy. Adjuvants may support immune responses to vaccine antigens by activation of dendritic cells (DC) and other components of innate immunity, and by creating a local depot of antigen at the site of immune activation. TLR agonists have emerged as effective adjuvants for inducing cellular and humoral immune responses [4]. and a recently-approved vaccine for hepatitis B has enhanced activity because it includes a TLR9 agonist as an adjuvant [5]. For experimental cancer vaccines, agonists for TLRs 3, 4, 7, and 9 have induced favorable cellular and/or humoral responses and may either be more effective than using incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA), or may enhance the activity of IFA [6,7,8,9,10]. However, remarkably little is known about the cellular and molecular effects of adjuvants containing TLR agonists at the vaccine site microenvironment (VSME), and few studies have evaluated the effects of any adjuvants over time at the VSME.

AS15 is a combination of a TLR4 agonist [3-O-desacyl-4′- monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL, produced by GSK)], a TLR9 agonist [CpG 7909 synthetic oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs], and Quillaja saponaria Molina, fraction 21 (QS-21, Licensed by GSK from Antigenics LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Agenus Inc., a Delaware, USA corporation) in a liposomal formulation [11, 12]. AS15 has been shown to support T cell and antibody responses to protein vaccines in several phase II and phase III clinical trials in melanoma and NSCLC [11,12,13,14,15], and those TLR4 and TLR9 agonists are employed in other experimental vaccines. We have previously reported immune response data from a clinical trial of vaccination with a MAGE-A3 protein plus AS15 [16]. Secondary endpoints of that study included evaluation of the VSME for immune cell infiltrates and immune signaling, and biopsies were obtained to enable those analyses. A primary goal of the present manuscript is to assess changes over time at the VSME induced by this regimen.

Prior work in a mouse model has shown that peptide vaccination with a TLR agonist in an aqueous adjuvant induced more durable immune responses than vaccination in IFA, and that IFA induced chronic inflammation at the VSME that recruited and retained T cells there[10]. However, we have also previously found that inflammatory adverse events at the vaccine site correlate with prolonged disease-free survival, suggesting that accumulation of immune cells and inflammation at the VSME may in fact be associated with improved clinical outcome in patients receiving these vaccines [17]. Additionally, in a separate clinical trial, we observed that adding IFA to a melanoma peptide vaccine led to higher and more durable T cell responses than using a TLR agonist alone [7]. These findings warrant further investigation into the local effects of vaccine adjuvants in human tissues and comparison between vaccine adjuvants. In the present study, we report changes over time in cellular infiltrates and gene expression in the VSME from each of the two clinical trials. We quantified innate and adaptive immune cell infiltration in the VSME and compared early responses (after one vaccine, at one week) and late responses (after multiple vaccine replicates, at weeks 3 and 7) of either AS15 or IFA. By quantifying the immune subsets accumulating in the VSME and associated immune signaling at those sites, we have generated more insight in the importance of adjuvant choice in creating vaccine site inflammation and ultimately systemic antitumor immune responses. We hypothesized that AS15 would promote less chronic inflammation and, thus, less accumulation of innate and adaptive immune cells at the VSME than IFA, and that AS15 would induce less T-cell retention, a stronger Th1-biased microenvironment, and reduced regulatory T-cell accumulation.

Materials and methods

Patients and trials

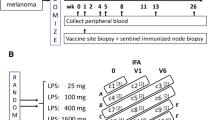

Tissue samples were obtained from patients enrolled in the Mel48 (NCT00705640) and Mel55 (NCT01425749) clinical trials at the University of Virginia, which have been reported [18,19,20]. For Mel48, 36 evaluable patients with resected stage IIB-IV melanoma were randomly assigned to 2 study groups based on vaccine regimen, each with 5 subgroups based on date of vaccine site biopsy (Fig. 1). Each patient received a 12-melanoma peptide (12MP) vaccine + tetanus helper peptide with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (Montanide ISA-51, Seppic, Inc, Paris, France) in one extremity, administered intradermal/subcutaneously. The majority of patients also received replicate immunizations of adjuvant only (group 1) or peptide vaccine + adjuvant (group 2), administered at a site distant from the original vaccination. Patients underwent biopsy of the replicate vaccine site on days 1, 8, 22, 50, or 85 (subgroups A-E, respectively), after 0, 1, 3, 6 and 6, replicate vaccines, respectively. For the present research project, patients who had biopsies at week 0 (day 1, groups 1A, 2A), week 1 (day 8, groups 1B, 2B), week 3 (day 22, groups 1C, 2C) or week 7 (day 50, groups 1D, 2D) were analyzed (See Supplemental Table 1 for characterization of sample analysis).

In Mel55, 25 eligible patients with resected stage IIB-IV melanoma were randomly assigned to 2 study groups. Each patient received a recombinant MAGE-A3 protein vaccine combined with AS15 Adjuvant System, either intramuscularly (group 1) or intradermal/subcutaneously (group 2), five times at alternating sides in 3-week intervals. Vaccine site biopsies were taken at two time points, on week 1 (day 8) and week 7 (day 50) for patients in group 2.

All patients were studied following informed consent, and with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval (HSR-IRB 13,498 and 15,398, respectively) and FDA approval (BB-IND #12,191, 14,654). At week 1, both Mel48 and Mel55 patients had received one vaccine. At week 3, Mel48 patients had received 3 vaccines at the same site. By week 7, Mel48 patients had received 6 vaccines at the same site and Mel55 patients had received 3 vaccines, two of which were at the same site.

Immunohistochemistry and quantification

Vaccine site biopsies were formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded by the Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (BTRF) at the University of Virginia. Tissues were stained by immunohistochemistry (IHC) with antibodies to CD1a, CD8 and CD20 (DakoCytomation, Denmark), CD4 (Vector, California), CD83 (Novocastra, Maryland), FoxP3 (eBioscience, California), peripheral node addressin (PNAd) and GATA3 (BD Pharmingen, California) and Tbet (Santa Cruz, Texas). The staining protocols used have been reported [19, 21]. Cell counts were enumerated with an automated approach (for CD4, CD8, CD45) or manually by a trained pathologist (for the remainder) and are reported as cells per millimeter squared. Automated cell counts were calculated by the Nikon Elements Software (Nikon, Melville NY) after scanning the slides with Aperio CS slide scanner (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove IL). The algorithm used was first tested by comparing automated and manual counts for selected regions from 10 slides. Resulting counts demonstrated a close correlation (R2 = 0.939, data not shown). Eosinophils were enumerated manually by a trained pathologist (JP) on Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) stained slides. Cells were enumerated separately in deep, mid and superficial layers of the dermis. For final analysis, average cell counts/mm2 for only the mid and superficial dermis layers were used to compare between trials. Where cell ratio was analyzed and compared, the values were converted to natural log transformed values prior to analysis. The two sample T test was used to test for differences between Mel48 and Mel55 results for each of the two time points, and for differences in time within Mel48. To guide interpretation and adjust for multiple comparisons, a p-value ≤ 0.005 is considered indicative of a potentially important difference.

RNA extraction and library preparation

Total RNA was isolated from cells collected at the VSME of patients from Mel48 (weeks 0, 1, and 3) and Mel55 (weeks 1 and 7). RNA extraction was performed using the RNeasy Lipid Tissue MiniKit (Qiagen), according to manufacturer instructions. RNA samples were processed for library preparation using the NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina), according to validated standard operating procedures established by the UVA School of Medicine’s Genome Analysis and Technology Core (RRID:SCR_018883). Briefly, total RNA was used to isolate mRNA, using NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (New England Biolabs, Inc), followed by fragmentation and first & second-strand cDNA synthesis and fragmentation, following manufacturer recommendations. The resulting cDNA was end-repaired, adenylated, and then subjected to sequence adapter ligation. The final purified libraries were quantified and sized using the Invitrogen Qubit 3 Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and Agilent Technologies 4200 TapeStation (Agilent).

Next-Generation sequencing run and QC

RNA sequencing was performed using the Illumina NextSeq 75 bp High Output sequencing kit reagent cartridge in conjunction with the Illumina NextSeq 500 (Illumina, San Diego, California; 75 cycles, single read sequencing), according to the standard manufacturer- recommended procedure. Samples were randomized into 4 groups and run sequentially on the Illumina NextSeq 500 for single-end sequencing. After transfer to the Illumina Base Space interface, the quality of the runs was assessed by the numbers of reads in millions passing filter and the % of indexed reads.

RNA sequencing analysis

RNAseq reads were assessed for quality using FastQC. Transcript abundances and were quantified against the human reference genome, (Gencode v28 Transcripts, Ensembl GRCh38) using Salmon [22] and read into the R statistical computing environment as gene-level counts using the tximport package. The DESeq2 Bioconductor package [23] was used to normalize for differences in sequencing depth between samples (using the default median-of-ratios method), estimate dispersion and fit a negative binomial model for each gene. The Benjamini Hochberg False Discovery Rate procedure [24] was then used to re-estimate the adjusted p-values. All statistical analyses and data visualization, including GAGE [25], were done using the R statistical computing environment and GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA).

Results

Human subjects

Both trials included patients without clinical evidence of disease, after resection of melanoma (at original diagnosis or restaged at recurrence). The 10 participants of the Mel55 trial whose vaccine site biopsies were evaluated in this study included 40% females, median age 53, stages IIIB-IV based on staging at recurrence, with 70% stage III (70% IIIB/C). The 23 participants of the Mel48 trial evaluated in this study included 30% females, median age 56, stages IIB-IV based on staging at recurrence, with 78% stage III (65% IIIB/C). Details are shown in Supplemental Table 1. All patients on both trials had been rendered clinically free of disease by surgery; so, they were also similar in having no measurable melanoma at the time of study entry.

Accumulation of innate immune cells at the VSME with AS15, compared to IFA

To assess immune cell accumulation over time in the VSME, vaccine site biopsies were assessed by IHC for patients treated with melanoma vaccines using AS15 (Mel55 trial) or IFA (Mel48 trial), at weeks 1 and 7. Histology images from Mel48 patients have been published [19]. Representative sections from the Mel55 trial are shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating cell aggregates through the dermis that vary among patients. At week 1, numbers of mature DC’s (CD83) were higher after IFA compared to AS15 (Fig. 3a, p < 0.001, and numbers of immature DC’s (CD1a) trended higher after IFA (Fig. 3b, p = 0.007). Eosinophils were rare in both patient subsets at week 1 (Fig. 3c). At week 7, the VSME induced with IFA had increased numbers of all three innate immune cell subsets, compared to the VSME induced with AS15 as adjuvant; however, when adjusted for multiple testing, none are significant (p > 0.005, Fig. 3a–c).

Number of immune cells per mm2 of vaccine site biopsies in both the superficial and mid deep layers of the skin. Displayed are number of CD83 + cells (a), CD1A + cells (b), and square root of Eosinophils (c), CD8+ cells (d), CD4+ cells (e), CD20+ cells (f), GATA3+ cells (g), Tbet+ cells (h) or FoxP3+ cells (i) week 1 and week 7 after the first vaccine in MEL48 (with IFA) and MEL55 (with AS15). All p values have been corrected for false-discovery rate as stated in the methods and statistical significance was determined at p < 0.005

Accumulation of adaptive immune cells at the VSME with AS15, compared to IFA

We also evaluated the accumulation of adaptive immune cells: CD4+, CD8+ and CD20+ lymphocytes in the dermis at the VSME. At week 1 (1 week after the first vaccine), CD8+ T cell density trended lower with IFA (Mel48) than with AS15 (Mel55) (Fig. 3d, p = 0.029). There were no significant differences between the two trials at week 1 in accumulation of CD4+ T cells (p = 0.079) or CD20+ B cells (p = 0.081, Fig. 3e,f). However, after 7 weeks, Mel48 VSMEs had increased accumulation of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and B cells compared to week 1, whereas patients in Mel55 did not (Fig. 3d–f). VSME densities of CD8 T cells and B cells were significantly greater at week 7 for Mel48 patients than Mel55 patients (p = 0.003, p < 0.0001, respectively) and there was a trend for more CD4 T cells (p = 0.015). These data suggest that repeat vaccination with IFA at the same site enhances inflammation and durable accumulation of T and B lymphocytes, whereas AS15 only induced short-term accumulation of T cells.

Vaccines sites that received IFA had higher expression of retention integrin subunits alpha1 and beta1 and homing receptor subunits alpha4 and beta7

We have previously observed that T cells accumulating at vaccine sites have high expression of retention integrins α1β1, α2β1, αEβ7 [18]. Therefore, we hypothesized that expression of these retention integrins, as well as the homing integrin α4β7, would be induced in highly inflamed vaccine sites induced by IFA in Mel48. To evaluate expression of these molecules, we compared VSME-derived gene expression data from Mel48 and Mel55 trials. For these studies, VSME biopsies were evaluated by RNAseq from weeks 1 and 7 from the Mel55 trial and from weeks 1 and 3 from the Mel48 trial. The alpha chains α1 and α2 only dimerize with β1, and αE only dimerizes with β7; thus, expression of α1β1, α2β1, αEβ7 can be evaluated by expression of the genes corresponding to the alpha chains (ITGA1, ITGA2, and ITGAE, respectively). ITGA4 and ITGB7 encode α4 and β7, respectively. Expression of ITGA1, ITGB1, ITGA4, and ITGB7 were significantly enhanced at week 3 post vaccination with IFA (Mel48 W3) compared to normal skin, Mel48 week 1 and Mel55 (Supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, ITGA2 (α2) and ITGAE (αE) did not increase in either trial, suggesting that cells accumulating at the vaccine sites treated with IFA may use alpha4beta7 to home and alpha1beta1 to be retained at the site.

Th2/Th1 and CD8/FoxP3 ratios at the VSME

To assess the Th1 and Th2 phenotype of T lymphocytes in the VSME, biopsies were evaluated by IHC for transcription factors Tbet, GATA3, and FoxP3, which mediate Th1, Th2, and Treg programming, respectively. There were more CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the VSME of Mel48 at week 7 compared to Mel55 (Fig. 3) [19]; thus, it is not surprising that more Tbet+, GATA3+ and FoxP3+ cells were evident at this time point (Fig. 3g–i); however, proportions of those cells are likely more informative about the VSME. At week 1, the GATA3/Tbet ratio was significantly lower in Mel55 than for Mel48 p = 0.004, Fig. 4a). However, by week 7, the GATA3/Tbet ratio was similarly low for both trials. This was explained by a significant decrease in the ratio in the Mel48 samples, as previously reported [19] and as evident in Fig. 4a (p = 0.005), but no change was evident in that ratio over time for Mel55 samples. However, the Th2/Th1 ratio remains above 1, indicating that, regardless of the adjuvant, the VSME appears to be Th2-dominant by this measure (Fig. 4a, c).

a Ratio of GATA3+ cells to Tbet+ cells in the VSME in MEL48 and MEL55 both week 1 and week 7 after the first vaccine. b Ratio of CD8+ cells to FoxP3+ cells in the VSME in MEL48 and MEL55 both week 1 and week 7 after the first vaccine. For panels a and b, means and standard deviations are shown in addition to values for each sample. c Relative proportions of FoxP3+, Tbet+, and GATA3+ cells in the VSME dermis are shown for both trials and both time points. All p values have been corrected for false-discovery rate as stated in the methods and statistical significance was determined at p < 0.005

Also evaluated was the accumulation of FoxP3+ cells, which likely represent regulatory T cells. At week 1, the proportions of FoxP3+ cells were similar in patients from both trials (Fig. 4c), and the CD8/FoxP3 ratios were similarly high (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, proportional density of FoxP3+ cells increased by week 7 in the IFA samples (Mel48, Fig. 4c), accompanied by a decrease in CD8/FoxP3 ratio (Fig. 4b, p = 0.003). The same change was not seen with vaccines containing AS15 (Mel55), so that the CD8/FoxP3 ratios at week 7 were significantly lower for Mel48 than for Mel55 (p < 0.001, Fig. 4b).

Peripheral node addressin is expressed in vaccine sites of patients treated with AS15 as adjuvant

Peripheral node addressin (PNAd) is the classic ligand for L-selectin, enabling naïve T cells to recognize high endothelial venules in lymph nodes as a critical first step enabling transmigration into the node [26]. We have previously reported that PNAd+ HEV-like vessels can be induced, in association with lymph node like structures, in the VSME of some patients after repeated injection of vaccines in IFA [21]. Staining the VSME for PNAd after AS15 injections identified PNAd+ vasculature, surrounded by immune cells in VSME biopsies of 3 out of 12 patients (4/22 specimens: 2/11 at week 1 and 2/11 at week 7, Fig. 5). This suggests that AS15 may be capable of generating tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) containing high-endothelial venues in some patients.

AS15 and IFA induce expression of TLS –associated genes

To evaluate factors that may contribute to TLS formation in AS15- and IFA-treated VSME, we compared VSME-derived gene expression data from both trials. A list of target genes was developed based upon a previously defined 12- chemokine TLS-associated gene signature[27], plus 6 additional genes (BAFF, APRIL, LIGHT, lymphotoxin alpha [LTA], lymphotoxin beta [LTB], CD20), which have been shown in other work to be correlated with TLS formation [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Compared to control normal skin, there were significant (p < 0.05) increases in expression of 16 of these 18 genes in the VSME skin 1 week after AS15 injection (Mel55 week 1, Fig. 6 & Supplemental Table 2). By week 7, mean expression had dropped in 5/18 of the TLS-associated genes, compared to the week 1 time point, with only 8 genes significantly increased at week 7 compared to normal skin (p < 0.05). These findings are consistent with the reduced immune cell accumulation upon repeat vaccination with AS15.

Individual gene expression of eighteen genes that have been previously associated with TLS formation: a BAFF, b APRIL, c LIGHT, d Lymphotoxin alpha, e Lymphotoxin beta, f CD20, g CCL2, h CCL3, i CCL4, j CCL5, k CCL8, l CXCL9, m CXCL10 n CXCL11, o CXCL13 p CCL18, q CCL19, r CCL21. Expression data was obtained from vaccine site biopsies of patients treated with IFA (MEL48) or AS15 (MEL55), as well as normal tissue obtained pre-vaccination for control purposes (n = 3). For patients treated with IFA, gene expression is shown at week (w) 1 (n = 5), and week 3 (n = 4), following initial vaccination at a site separate from the biopsied tissue. For patients treated with AS15, gene expression is shown at week 1 (n = 10) and week 7 (n = 9), following initial vaccination at a distant site. For factors of significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; derived from differential gene expression

In contrast, in IFA-treated samples, there were no significant increases in TLS-associated gene expression over control at week 1 (Mel48 week 1, Fig. 6). Compared to the AS15 treated samples, mean expression at week 1 was significantly lower in the IFA-treated samples for 4 of the genes. However, expression of these TLS-associated genes increased significantly upon repeat vaccination with IFA. By week 3, 16/18 genes were more highly expressed in IFA treated patients over control normal tissue (p < 0.05), with 16 of them significantly higher in IFA-treated samples than in AS15 treated samples after the 3rd vaccine.

Comprehensive analysis of changes at vaccine site after AS15 adjuvant

In addition to the TLS-associated gene signature, we aimed to more comprehensively analyze changes in gene expression at the VSME post AS15 injection and to compare these to known gene expression changes by IFA [36]. Differential gene expression was determined as > fivefold change over normal skin with and adjusted P-value of < 0.05 [37]. Overall, AS15-containing vaccines induced a total of 657 genes that were differentially expressed for both time points combined, with 554 upregulated and 103 downregulated genes (Supplemental Fig. 2a, b). The vast majority of differentially expressed genes were only present at day 8 post vaccination, though 149 (up) and 58 (down) were differentially expressed at both time points (Supplemental Fig. 2a, b). Genes upregulated at both time points included T cell markers, DC markers and granzymes. Similarly, pathways for T cell receptor signaling, antigen processing and presentation and leukocyte trafficking were upregulated in both time points, compared to normal skin (Supplemental Fig. 3). This suggests that, despite the lower and less durable accumulation of T cells and DCs at the VSME of AS15 vaccinated patients when compared to Mel48, they are significantly more present and durable when compared to normal skin. Therefore, AS15 does induce durable immune accumulation at the vaccine site, though not to the same extent as IFA.

AS15 and IFA induced components of FAS-mediated apoptosis pathway

Our data showed that despite a larger and more durable accumulation of DC and T cells at the VSME with IFA compared to AS15, there was significant and sustained increased T cell gene expression and other immune-related pathways with AS15 compared to normal skin. Murine studies have shown that IFA actually induced high accumulation at the VSME, but at the same time induced T cell deletion and immune suppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and FAS-FASL driven T cell killing [10]. Thus, we hypothesized that MDSC-related genes and genes involved in FAS signaling were induced after IFA but not AS15. Interestingly, MDSC-specific genes were not upregulated by either IFA or AS15 besides generic myeloid marker CD14 (Fig. 7a–d). In fact, in addition to previously reported Arginase-1[36], GITR and Syndecan-4 were downregulated after IFA. All three MDSC-related genes were unchanged after AS15 compared to control skin (Fig. 7b–e). Other suppressive molecules PD-L1 and IDO were increased significantly after IFA and AS15, though to a lesser extent and not durably with AS15 compared to IFA (Fig. 7f, g). This suggests there are suppressive mechanisms at play at the VSME of patients vaccinated with IFA or AS15. Similarly, components of the FAS-mediated apoptosis pathway were induced with both AS15 and IFA, though this was only extended to the later time point with IFA (Fig. 7h–l). However, inhibitor of FAS-mediated killing FLIP was expressed at high levels at the same time point after IFA (Fig. 7m), though never with AS15, suggesting that there may be negative feedback loop dampening T cell deletion after IFA but not AS15. Thus, accumulation of immune cells, after vaccination with AS15 may not be accompanied by inhibition or deletion to the same extent as IFA, leading to fewer in number, but more functional immune cells.

Individual gene expression of MDSC-related genes (a–d), inhibitory molecule genes (e–g) and genes involved in FAS-mediated apoptosis (h–m). Expression data was obtained from vaccine site biopsies of patients treated with IFA (MEL48) or AS15 (MEL55), as well as normal tissue obtained pre-vaccination for control purposes (n = 3). For patients treated with IFA, gene expression is shown at week (w) 1 (n = 5), and week 3 (n = 4), following initial vaccination at a site separate from the biopsied tissue. For patients treated with AS15, gene expression is shown at week 1 (n = 10) and week 7 (n = 9), following initial vaccination at a distant site. For factors of significance: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; derived from differential gene expression

Discussion

In this study, we have analyzed the VSME following immunization with a MAGE-A3/AS-15 vaccine at two time points and compared findings to similar time points from a separate clinical trial using IFA as an adjuvant. There were significant differences in the VSME between the two immunotherapeutic approaches. The findings support our hypothesis that a vaccine containing AS15 would induce less accumulation of innate and adaptive immune cells, as well as FoxP3+ cells, at the VSME than a vaccine incorporating IFA. Lymphocyte accumulation differed significantly between the two groups, with CD8+ T cells, B cells, and FoxP3+ cells all accumulating within the VSME in significantly higher numbers by week 7 in Mel48 samples than Mel55. While the increase in FoxP3+ cells within the IFA-induced VSME at week 7 could suggest a transition to a more suppressive environment over time, it is also important to recognize that more regulatory T cells are expected in an inflammatory environment, as CCL22 production by activated CD8 T cells effectively recruits these cells. Additionally, despite the greater accumulation of immune cells at the VSME with IFA, expression of DC- and T cell-related genes was induced with AS15 compared to normal skin. Furthermore, in addition to greater FoxP3+ cell accumulation, CD8 T cell inhibitory pathways, including PD-L1 and IDO, were also increased with IFA, compared to AS15, though both adjuvants induced PD-L1 and IDO over normal skin. Neither induced MDSC suppressive pathways. These results suggest that AS15 induces a less suppressive environment than IFA, but this is accompanied with low levels of immune cell accumulation. Future analysis will have to determine whether the suppressive and inhibitory mechanisms at the VSME are a direct result of the increased inflammation and whether this inflammation and accumulation of immune cells is beneficial or harmful to the induction and/or maintenance of the systemic response.

Regardless of the density of lymphocytes at the vaccine site, there appears to be a Th2-dominant phenotype, both in Mel48 and Mel55 at weeks 1 and 7. The Th2 cytokine IL-5 can induce eosinophils; thus, additional evidence for Th2 dominance in the VSME after IFA included a marked accumulation of eosinophils identified at week 7 for the Mel48 patients[19, 38]; however, this was not seen in the Mel55 trial with AS15 (Fig. 3c), suggesting that the slight GATA3 dominance in Mel55 was not sufficient to enhance eosinophils in the VSME, and that the much higher GATA3/Tbet ratio early in IFA-injected sites may have a greater biologic effect.

We have previously reported that CD8+ T cells retained at vaccine sites have increased expression of the retention integrins α1β1, α2β1, and αEβ7, which may explain a mechanism for their retention in the peripheral tissues [18]. Here we find that gene expression for integrin subunits α1and β1 are significantly induced by vaccination with IFA, suggesting an increase in infiltration of cells expressing the α1β1 integrin. T cells expressing α1β1 (VLA-1, CD49a) have been identified as long-lived resident-memory T cells in peripheral tissues [39,40,41]; so, their presence in vaccine sites may be favorable, and is not entirely consistent with the findings in murine studies where T cells recruited to vaccine sites do not survive there long-term [10].

The enhanced accumulation of B cells in the Mel48 trial patients may reflect TLS development, as B cell clusters are critical components of TLS. TLS accommodate recruitment and activation of naïve T cells, are observed in chronically inflamed tissues, and can support antigen-specific T cell responses [42,43,44,45]; so, the formation of these structures could potentially enhance T cell reactivity of vaccines. We have previously demonstrated that IFA-containing vaccines can induce formation of TLS in the VSME, including (DC-LAMP+ CD83+) DC in 12/18 patients [21]. Upon single vaccination with IFA alone, TLS formation was somewhat disorganized, peaked within 1 week following injection, and dissipated after about 2 weeks [21]. However, repeated vaccination with IFA, together with melanoma peptides, induced more prominent and organized TLS formation, including organized B and T cells areas as well as expression of lymphoid-associated chemokines, including CXCL13 and CCL21 [21]. In the present study, we observed the changing expression of TLS-associated genes over time, following both single and repeat vaccination with IFA or AS15. Our data support and expand upon our previous findings. One week following one vaccine with IFA, a modest increase in TLS-associated gene expression was observed compared to normal tissue. Repeat vaccination with IFA appears to augment this response, as demonstrated by the dramatic increase in gene expression seen when comparing the effects of 1 versus 3 vaccinations.

The immune cell infiltration data suggest that IFA enhances infiltration of immature and mature DC. Classically, inflammation in the skin induces maturation of Langerhans cells and dermal DC, and those maturing DC migrate to the draining nodes within hours to a few days [46,47,48]. Thus, the greater accumulation of mature (CD83+) DC in the IFA group suggests that this adjuvant either slows DC migration to the draining nodes or supports DC maturation on a continuing basis after vaccine administration. It is possible that many of the adaptive immune cells present in the VSME at week 7 in Mel48 samples may be residing in TLS, potentially serving as sites of further, long-term antigen-specific immune cell activation in situ. It may follow then that the accumulation of DC in the VSME upon vaccination with IFA can be explained, at least in part, by retention of DC in TLS in the VSME, where they may be able to support presentation of antigen locally.

While our data also support the ability of AS15 to induce TLS formation, the extent, composition, and timeline for development appear to differ from that of IFA. Specifically, single vaccination with AS15 induced TLS-associated gene expression to a stronger degree than that of single vaccination with IFA. However, despite the increased gene expression, AS15-treated biopsy sites had lesser accumulation of CD83+ DC, compared to IFA-treated sites at a similar time point. Furthermore, unlike the augmented response seen upon repeated vaccination with IFA, TLS-associated gene expression either declined or remained stable following repeat vaccination with AS15. PNAd staining and immune cell infiltration data corroborate this finding, as the number of PNAd+ biopsy sites did not increase with repeated AS15 vaccination (Fig. 5). Similarly, the accumulation of immune cells remained stable between the two vaccination time points. Thus, it appears that while single vaccination with AS15 induces TLS-gene expression to a greater degree than IFA after 1 week, the latter agent may induce secondary effects that evolve over time but support stronger, more durable TLS formation. Previous studies have found that the structure and formation of TLS’s vary depending upon certain variables, including anatomical site and tumor type [35]. In light of our findings, it seems plausible that vaccination composition may also affect the formation and possibly even the function of TLS.

A limitation of the comparisons between the two studies is that, in addition to differences in the adjuvants, there were differences in the antigen used between the trials: AS15 was combined with recombinant MAGE-A3 protein, whereas IFA was combined with 12 short melanoma peptides. Protein antigens and peptide are different in that protein must be processed by professional APCs, whereas peptides may bind directly to cell surface MHC. However, both vaccines have induced both CD8 and CD4 T cell responses [3, 16, 18]. Also, the peptide vaccine included a MAGE-A3 peptide and three other MAGE-A antigens [18, 49]; so, there is some antigenic similarity with the MAGE-A3 protein. We have previously found that immune cell infiltrates and gene expression changes induced locally at the VSME appear to be attributable to the adjuvant more than to the antigen (19, 36). Thus, we anticipate that differences at the VSME between these studies are likely to be driven primarily by the adjuvant, though we acknowledge potential impact of the antigen on the cellular and gene expression changes. Another limitation of the present study is that biopsies were evaluated at limited time points after vaccination, whereas VSME infiltrates evolve over time. IFA-based emulsions create a long-term antigen-depot, but aqueous vaccines like the MAGE-A3/AS15 vaccines likely dissipate over hours to days, which coincides with clinical resolution of initial redness and inflammation. Since biopsies were taken 7 days after vaccine administration, there may well have been strong effects on T cell activation within those 7 days, which are missed by the time of biopsy. Thus, evaluation 1–2 days after AS15 vaccines may reveal greater inflammatory cell infiltrates than those one week after the vaccine. Our results from week 7 are also limited by differences in vaccine schedules. because the number of vaccines before week 7 differ. However, the VSME evaluations at week 1 are comparable.

In summary, our data highlight effects of vaccine adjuvants AS15 and IFA on the VSME. We found less accumulation of innate and adaptive immune cells within the AS15-induced VSME, compared to that of IFA. Though AS15 still induced T cell- and DC-related genes compared to normal skin. The AS15-induced VSME featured a lower number of inflammatory cells, as well as less accumulation of FoxP3+ cells, while IFA induced increases in FoxP3+ cells over time. Similarly, AS15 induced lower levels of CD8 inhibitory pathways PD-L1 and IDO. The CD8/FoxP3 ratio was higher with AS15 vaccines than IFA-containing vaccines, suggesting that the reduction in FoxP3+ cells with AS15 is due to more than just a proportional decrease in overall immune cell infiltration. Interestingly, AS15 vaccines induced a more Th1-dominant VSME than IFA vaccines, at 1 week, but this difference did not persist with repeated vaccination based on biopsies at week 7. Evidence of TLS formation was demonstrated with both adjuvants, though PNAd+ vasculature was observed in a smaller number of patients on the Mel55 trial than we have previously reported with IFA-based vaccines. Similarly, TLS-associated gene signature expression appeared to be more transient in vaccination site biopsies taken from AS15 treated patients, compared to their IFA treated counterparts. Our findings represent new findings about the dynamic effects of adjuvants on the VSME and suggest the need for future studies to determine which of these effects support optimal systemic T cell responses to vaccines.

Availability of data and materials

The IHC data used in this manuscript will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The RNA sequencing data will be made available publicly prior to publication.

References

Cheever MA, Higano CS (2011) PROVENGE (Sipuleucel-T) in prostate cancer: the first FDA-approved therapeutic cancer vaccine. Clin Cancer Res 17:3520–3526. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-10-3126

Schwartzentruber DJ, Lawson DH, Richards JM et al (2011) gp100 peptide vaccine and interleukin-2 in patients with advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 364:2119–2127

Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Smolkin ME et al (2010) Immunogenicity for CD8+ and CD4+ T cells of two formulations of an incomplete Freund’s adjuvant for multipeptide melanoma vaccines. J Immunother 33:630–638. https://doi.org/10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181e311ac

Gnjatic S, Sawhney NB, Bhardwaj N (2010) Toll-like receptor agonists: are they good adjuvants? Cancer J 16:382–391

Hyer RN, Janssen RS (2019) Immunogenicity and safety of a 2-dose hepatitis B vaccine, HBsAg/CpG 1018, in persons with diabetes mellitus aged 60–70years. Vaccine 37:5854–5861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.08.005

Sabbatini P, Tsuji T, Ferran L et al (2012) Phase I trial of overlapping long peptides from a tumor self-antigen and poly-ICLC shows rapid induction of integrated immune response in ovarian cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 18:6497–6508. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-12-2189

Melssen MM, Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA et al (2019) A multipeptide vaccine plus toll-like receptor agonists LPS or polyICLC in combination with incomplete Freund’s adjuvant in melanoma patients. J Immunother Cancer 7:163. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40425-019-0625-x

Baumgaertner P, Costa Nunes C, Cachot A et al (2016) Vaccination of stage III/IV melanoma patients with long NY-ESO-1 peptide and CpG-B elicits robust CD8(+) and CD4(+) T-cell responses with multiple specificities including a novel DR7-restricted epitope. Oncoimmunology 5:e1216290. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2016.1216290

Speiser DE, Lienard D, Rufer N, Rubio-Godoy V, Rimoldi D, Lejeune F, Krieg AM, Cerottini JC, Romero P (2005) Rapid and strong human CD8+ T cell responses to vaccination with peptide, IFA, and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 7909. J Clin Invest 115:739–746

Hailemichael Y, Dai Z, Jaffarzad N et al (2013) Persistent antigen at vaccination sites induces tumor-specific CD8(+) T cell sequestration, dysfunction and deletion. Nat Med 19:465–472

Kruit WH, Suciu S, Dreno B et al (2013) Selection of immunostimulant AS15 for active immunization with MAGE-A3 protein: results of a randomized phase II study of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Melanoma Group in Metastatic Melanoma. J Clin Oncol 31:2413–2420

Kruit WH, Suciu S, Dreno B, et al (2008) Immunization with recombinant MAGE-A3 protein combined with adjuvant systems AS15 or AS02B in patients with unresectable and progressive metastatic cutaneous melanoma: A randomized open-label phase II study of the EORTC Melanoma Group (16032–18031). J Clin Oncol 26: abstract 9065.

Gutzmer R, Rivoltini L, Levchenko E et al (2016) Safety and immunogenicity of the PRAME cancer immunotherapeutic in metastatic melanoma: results of a phase I dose escalation study. ESMO Open 1:e000068. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2016-000068

Vansteenkiste JF, Cho BC, Vanakesa T et al (2016) Efficacy of the MAGE-A3 cancer immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy in patients with resected MAGE-A3-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (MAGRIT): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 17:822–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(16)00099-1

Dreno B, Thompson JF, Smithers BM et al (2018) MAGE-A3 immunotherapeutic as adjuvant therapy for patients with resected, MAGE-A3-positive, stage III melanoma (DERMA): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 19:916–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(18)30254-7

Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Olson WC et al (2016) A randomized pilot trial testing the safety and immunologic effects of a MAGE-A3 protein plus AS15 immunostimulant administered into muscle or into dermal/subcutaneous sites. Cancer Immunol Immunother 65:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-015-1770-9

Hu Y, Smolkin ME, White EJ, Petroni GR, Neese PY, Slingluff CL Jr (2014) Inflammatory adverse events are associated with disease-free survival after vaccine therapy among patients with melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 21:3978–3984. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3794-3

Salerno EP, Shea SM, Olson WC, Petroni GR, Smolkin ME, McSkimming C, Chianese-Bullock KA, Slingluff CL Jr (2013) Activation, dysfunction and retention of T cells in vaccine sites after injection of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, with or without peptide. Cancer Immunol Immunother 62:1149–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-013-1435-5

Schaefer JT, Patterson JW, Deacon DH, Smolkin ME, Petroni GR, Jackson EM, Slingluff CL Jr (2010) Dynamic changes in cellular infiltrates with repeated cutaneous vaccination: a histologic and immunophenotypic analysis. J Transl Med 8:79. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5876-8-79

Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Olson WC et al (2016) A randomized pilot trial testing the safety and immunologic effects of a MAGE-A3 protein plus AS15 immunostimulant administered into muscle or into dermal/subcutaneous sites. Cancer Immunol Immunother 65:25–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-015-1770-9

Harris RC, Chianese-Bullock KA, Petroni GR, Schaefer JT, Brill LB 2nd, Molhoek KR, Deacon DH, Patterson JW, Slingluff CL Jr (2012) The vaccine-site microenvironment induced by injection of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant, with or without melanoma peptides. J Immunother 35:78–88. https://doi.org/10.1097/CJI.0b013e31823731a4

Patro R, Duggal G, Love MI, Irizarry RA, Kingsford C (2017) Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 14:417–419. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4197

Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Roy Stat Soc B 57:289–300

Luo W, Friedman MS, Shedden K, Hankenson KD, Woolf PJ (2009) GAGE: generally applicable gene set enrichment for pathway analysis. BMC Bioinform 10:161. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-161

Girard JP, Moussion C, Förster R (2012) HEVs, lymphatics and homeostatic immune cell trafficking in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol 12:762–773. https://doi.org/10.1038/nri3298

Messina JL, Fenstermacher DA, Eschrich S et al (2012) 12-Chemokine Gene Signature Identifies Lymph Node-like Structures in Melanoma: Potential for Patient Selection for Immunotherapy? Sci Rep 2:765. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00765

Jonsson MV, Szodoray P, Jellestad S, Jonsson R, Skarstein K (2005) Association between circulating levels of the novel TNF family members APRIL and BAFF and lymphoid organization in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. J Clin Immunol 25:189–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-005-4091-5

Grogan JL, Ouyang W (2012) A role for Th17 cells in the regulation of tertiary lymphoid follicles. Eur J Immunol 42:2255–2262. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.201242656

Barone F, Gardner DH, Nayar S, Steinthal N, Buckley CD, Luther SA (2016) Stromal fibroblasts in tertiary lymphoid structures: a novel target in chronic inflammation. Front Immunol 7:477. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00477

Ciccia F, Rizzo A, Maugeri R et al (2017) Ectopic expression of CXCL13, BAFF, APRIL and LT-beta is associated with artery tertiary lymphoid organs in giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis 76:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209217

Pipi E, Nayar S, Gardner DH, Colafrancesco S, Smith C, Barone F (2018) Tertiary lymphoid structures: autoimmunity goes local. Front Immunol 9:1952. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2018.01952

Weinstein AM, Storkus WJ (2015) Therapeutic lymphoid organogenesis in the tumor microenvironment. Adv Cancer Res 128:197–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.acr.2015.04.003

Jing F, Choi EY (2016) Potential of cells and cytokines/chemokines to regulate tertiary lymphoid structures in human diseases. Immune Netw 16:271–280. https://doi.org/10.4110/in.2016.16.5.271

Engelhard VH, Rodriguez AB, Mauldin IS, Woods AN, Peske JD, Slingluff CL Jr (2018) Immune cell infiltration and tertiary lymphoid structures as determinants of antitumor immunity. J Immunol 200:432–442. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1701269

Pollack KE, Meneveau MO, Melssen MM et al (2020) Incomplete Freund’s adjuvant reduces arginase and enhances Th1 dominance, TLR signaling and CD40 ligand expression in the vaccine site microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-000544

Berendam SJ, Koeppel AF, Godfrey NR et al (2019) Comparative transcriptomic analysis identifies a range of immunologically related functional elaborations of lymph node associated lymphatic and blood endothelial cells. Front Immunol 10:816. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.00816

Takatsu K, Nakajima H (2008) IL-5 and eosinophilia. Curr Opin Immunol 20:288–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.001

Mackay LK, Stock AT, Ma JZ, Jones CM, Kent SJ, Mueller SN, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Gebhardt T (2012) Long-lived epithelial immunity by tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells in the absence of persisting local antigen presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:7037–7042

Haddadi S, Thanthrige-Don N, Afkhami S, Khera A, Jeyanathan M, Xing Z (2017) Expression and role of VLA-1 in resident memory CD8 T cell responses to respiratory mucosal viral-vectored immunization against tuberculosis. Sci Rep 7:9525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09909-4

Mackay LK, Rahimpour A, Ma JZ et al (2013) The developmental pathway for CD103(+)CD8+ tissue-resident memory T cells of skin. Nat Immunol 14:1294–1301

Neyt K, Perros F, GeurtsvanKessel CH, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN (2012) Tertiary lymphoid organs in infection and autoimmunity. Trends Immunol 33:297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2012.04.006

Hayasaka H, Taniguchi K, Fukai S, Miyasaka M (2010) Neogenesis and development of the high endothelial venules that mediate lymphocyte trafficking. Cancer Sci 101:2302–2308. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01687.x

Hiraoka N, Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R (2016) Tertiary Lymphoid Organs in Cancer Tissues. Front Immunol 7:244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2016.00244

Dieu-Nosjean MC, Giraldo NA, Kaplon H, Germain C, Fridman WH, Sautes-Fridman C (2016) Tertiary lymphoid structures, drivers of the anti-tumor responses in human cancers. Immunol Rev 271:260–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/imr.12405

Cumberbatch M, Kimber I (1992) Dermal tumour necrosis factor-alpha induces dendritic cell migration to draining lymph nodes, and possibly provides one stimulus for Langerhans’ cell migration. Immunology 75:257–263

Clausen BE, Kel JM (2010) Langerhans cells: critical regulators of skin immunity? Immunol Cell Biol 88:351–360. https://doi.org/10.1038/icb.2010.40

Said A, Weindl G (2015) Regulation of Dendritic Cell Function in Inflammation. J Immunol Res 2015:743169. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/743169

Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA et al (2007) Immunologic and clinical outcomes of a randomized phase II trial of two multipeptide vaccines for melanoma in the adjuvant setting. Clin Cancer Res 13:6386–6395. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0486

Acknowledgements

We thank the Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility (BTRF) for their help with purifying RNA from or paraffin embedding of patient tumor materials and the UVA School of Medicine’s Genome Analysis and Technology Core (GATC) for the RNAseq analyses, and the UVA Bioinformatics Core for data analysis.

Funding

This project was funded by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA (for the Mel55 trial—NCT01425749) and the Beirne Carter Center Immunology Training Grant T32AI007496. Support was also provided by NIH R01CA057653, Clinical Laboratory and Integration Project award from the Cancer Research Institute and by the University of Virginia Cancer Center Support Grant (NIH/NCI P30CA044579: Clinical Trials Office, Biorepository and Tissue Research Facility, Flow Cytometry Core, Genome Analysis and Technology Core, Bioinformatics Core, and Biomolecular Core Facility) and the Rebecca C. Harris Fellowship. Additional philanthropic support was provided by an anonymous donor. The Beirne Carter Center for Immunology Research provided flow cytometry support. We appreciate the work of Patrice Neese, Carmel Nail and Kathleen Haden for administering vaccines and for recording and managing toxicities. Appreciation also goes to clinical research coordinators Emily Allred, and Chris Blackwell.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MMM, JP, KEP, and CLS analyzed and interpreted IHC data. MMM and CLS drafted and/or substantially revised the manuscript. JP and DHD stained and enumerated immune cells within IHC materials. MES and GRP performed statistical analysis for the IHC results. AFK, SDT, KEP, KSC, AH, and MOM obtained, assembled and/or performed statistical analysis for the RNAseq results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

C.L. Slingluff Jr. reports receiving commercial research grants from Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, 3 M, and Celldex; has ownership interest (including patents) in several of the peptides used in the 12MP vaccine with UVA Licensing and Ventures Group; and is a consultant/advisory board member for Immatics, Curevac, and Polynoma. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Clinical trials Mel48 and Mel55 were performed with IRB (#13498 and #15398, respectively) and FDA approval and are registered with Clinicaltrials.gov under NCT00705640 (Mel48) and NCT01425749 (Mel55). Patients provided written informed consent to participate.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Melssen, M.M., Pollack, K.E., Meneveau, M.O. et al. Characterization and comparison of innate and adaptive immune responses at vaccine sites in melanoma vaccine clinical trials. Cancer Immunol Immunother 70, 2151–2164 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02844-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00262-020-02844-w