Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to explore how sonologists utilize cine images in their routine practice.

Methods

A 10-question, multiple choice survey was distributed to members of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. The survey queried respondent’s routine inclusion of cines for ultrasound examinations in normal and abnormal studies in addition to questions related to respondent’s practice type, geographic location, number of radiologists interpreting ultrasound examinations, and ultrasound imaging workflow.

Results

Sixty-five percent of respondents are in academic practice. Geographic location of practice, number of radiologists in the practice who interpret ultrasound, and whether the sonologist was on site where the examinations were performed was variable. Of respondents, 97% of used both static and cine images for abnormal/positive examinations and 82% used both for normal/negative studies.

Conclusion

Nearly all respondents, who are mostly in academic practice, report using both static and cine images for all ultrasound examinations in their practice.

Graphical abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A crucial component of any radiology department, ultrasound imaging is a widely available, cost-effective, real-time imaging modality that does not expose patients to ionizing radiation. The American College of Radiology® (ACR®) and American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine® (AIUM®) publish practice parameters and guidelines for performing diagnostic ultrasound as well as minimum standards for accreditation. [1,2,3,4]. These requirements are largely focused on static image acquisition with little guidance for other aspects of the examination, including the standard use of dynamic or cine imaging, who should primarily perform the examination in real time, (i.e., sonographer or radiologist) or whether images should be reviewed by a physician prior to patient release from the imaging department.

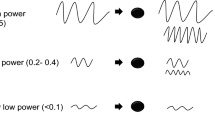

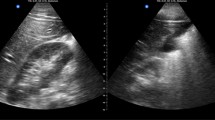

Radiology practices may also utilize cinematic images in addition to or replacement of static acquisition of ultrasound images. Cinematic ultrasound imaging (also known as cine, cine loop, video clip, and sweeps), hereafter referred to as “cine,” allows continuous acquisition of two-dimensional (2D) images with a video recording that can be archived and viewed in PACS [5]. Potential advantages to cines include the ability to better evaluate a structure or finding that may partially or completely exclude on static images as well as the ability to play/pause/replay the video clip to allow detailed analysis or aid in distinguishing a true finding from artifact. Cines may also better help to localize a lesion within an organ and to better compare a lesion across multiple exams. Thyroid ultrasound is a classic example, whereby comparison of multiple thyroid nodules is often more efficient when cines are used to compare multiple nodules over time and multiple examinations. Some studies point to a decrease in the need to re-scan patients and patient call-backs for indeterminate findings [6]. When obtained in place of static images, scanning time may be shortened. However, when obtained in addition to multiple static images, capturing multiple cines may increase both scan time and radiologist review and interpretation time. While there is some literature that points to improved accuracy/confidence with additional cine sweeps, these data are from specialized ultrasound examinations in fetal heart conditions [7, 8]. There is a lack of literature in the utility of cines in general adult ultrasound. The addition of cine images suggests there is a perceived increased confidence and accuracy in ultrasound interpretation, particularly in cases where images are reviewed by radiologists later. A sonographer may obtain cine images to improve reproducibility of examination findings or when they are unsure of findings. Yet, data to support this perception are limited in the literature, with most published studies from a single institution, with small sample size and compared sonologists personally scanning to sonographer scanning with “offline” review. [9, 10].

The AIUM® practice parameters for documentation of an ultrasound examination state that dynamic imaging may be required or preferred for some types of examinations, but parameters regarding specific methods for acquisition are vague [11]. Current literature lacks information on common practice and/or standardization for using cine imaging. There is lack of clarity on whether cine images should supplant or augment static images and whether the use of cine imaging increases diagnostic accuracy and what impact cines have on overall image acquisition or interpretation times. The aim of this study was explored how sonologists utilize cine images in their routine practice.

Methods

A 10-question, multiple choice survey (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) (Appendix 1) was distributed via email invitation to the email distribution list of the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU) membership. The primary authors of the study and institutional colleagues created and approved the study questionnaire. The study design, aims, request for participation, and survey questions required review and approval of the SRU executive board prior to distribution to SRU membership. The invitation to participate in the study was distributed by the SRU on behalf of the authors requesting participation. All email recipients of the SRU were invited to participate. The survey remained open for response for 3 weeks with 1 reminder email for participation. Sixty-five members completed the survey and all were included in the analysis.

Mixed effects logistic regression was used to evaluate factors associated with the use of cine images. Candidate covariates considered included: type of finding (normal vs abnormal), use of split screens, number of radiologists at the practice, geography of practice, and type of practice setting. The outcome, whether cine was used, was first regressed as a function of all candidate covariates (the ‘full’ model). We included radiologist as an R-side compound symmetric random effect to account for within-radiologist correlation. Backwards elimination was utilized to yield a final model. Mixed effects logistic regression was also employed to determine geographical practice location was associated with cine use. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare whether cines versus static images were obtained in studies with negative/normal findings as well as in studies with positive/abnormal findings. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statically significant.

Results

Of 500 email recipients, 461 members viewed the invitation and 65 completed the survey (response rate of 14%). There was 100% response rate for 7 of the 10 survey questions. Of the remaining 3 questions, two had a 98% response rate (64/65) and the other showed a 97% response (63/65).

Demographics and logistical workflow of practice settings

Demographics of practice setting and logistical workflow are shown in Table 1. Sixty-five percent of respondents practice in an academic setting. The next largest proportion of respondents, 18%, indicated their practice as “other,” which was largely described as a hybrid of mixed academic and private practice. Geographic practice setting and number of radiologists who interpret ultrasound were variable among respondents. Most respondents indicated variable presence at imaging locations due to the number of imaging sites served by their practice. Thus, there was a variety of daily practice workflow regarding radiologist involvement of image acquisition/review. Those who responded as ‘other’ also described a hybrid type model of reviewing some, but not all cases depending on physical presence of a radiologist on site with the patient.

Figure 1 summarizes the use of cine images for normal and abnormal imaging findings and shows that the majority of practices use both static and cine images for all examinations (normal and abnormal imaging findings).

Table 2 summarizes the percentage of respondents’ who indicated when a cine clip was obtained for a specific individual body organ in cases where there were no abnormal findings (normal/negative) and when the study did have positive and/or abnormal findings. Free responses to the “other” category included: soft tissues, hernias, palpable masses, and cervical lymph nodes. It was statistically more likely to use only static images for normal/negative exams (16.9%) compared with cine only negative exams (1.5%), P = 0.0043. It was uncommon to use only static images (3.1%) or cine only (0.0%) for abnormal/positive exams and there was not significant difference, P = 0.50. The predicted probability of cine use was 0.97 [95% CI (0.88, 0.99)] for abnormal findings and 0.83 [95% CI (0.71, 0.90)] for normal findings.

There was a statistically significant likelihood that cines were obtained when there were abnormal/positive findings as compared to normal/negative findings, except when imaging the thyroid or “other” organs. Sonographers perform ultrasound examinations in all but 1% of practices. There was variability as to whether the radiologist reviews images before the patient leaves the imaging center.

Discussion

Our results suggest that cine clips are widely used in ultrasound practice, irrespective of practice location, geographic practice setting, or number of radiologists in the practice interpreting ultrasound. Cines were statistically more likely to be obtained when there were abnormal imaging findings. However, cine images are not equally required nor specifically recommended for accreditation nor specifically addressed in practice parameters. For example, when accrediting general adult ultrasound, the ACR accepts cine images for imaging of only three organs: scrotum, ovaries, or thyroid. For other abdominal ultrasound studies, cine images are not accepted for accreditation purposes [1, 2]. Further, practice parameters are not prescriptive on the incorporation of cine images in technique or documentation [12,13,14]. This absence suggests that cines are of less importance when scanning most organs, although literature supports this indication.

Results of this survey indicate a gap between accreditation requirements and real-world practice. Therefore, the factors driving the decision to include cine images in standard practice are unclear, and further investigation into these factors should be explored. As previously noted, the supplementation of cines to static images indicates a perceived increased confidence and accuracy in ultrasound interpretation, but the literature to support this is lacking [9, 10]. Because cines cannot replace static images for accreditation purposes in most ultrasound studies, one may infer that cines are generally used as a supplement to static images, ultimately increasing the total number of images necessary for a sonographer to obtain and a radiologist to interpret. This could have downstream impacts on patient care and practice operations as studies may take longer to complete and interpret. Conversely, if cines are found to be an equivalent to static images, there may be opportunity to decrease image acquisition and interpretation time, which could improve access. However, the current state lacks guidelines, leaving practices and radiologists to determine how to best utilize cines in their setting. Evidence-based recommendations should be developed to provide radiology practices with guidance on best practices for using cine images for ultrasound examinations, including orientation and position of the probe during scanning, length of the cine clip, frame rate, and image labeling.

Our study has several limitations, notably a small sample size of 65 respondents from a selected group of radiologists, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound. Small sample size thus limits the power of this study. The largest proportion of respondents practice in the academic setting, therefore, these results may not reflect the broader population of ultrasound practices, particularly private practice outpatient and community hospital practices. Furthermore, given the audience of this survey, radiologists with a strong focus in ultrasound imaging, respondents to this survey may be more likely to use cine images compared to other radiologists. Additionally, this study assessed whether cines were regularly employed in respondents’ practices but specific imaging protocols for respondents’ practices of acquiring cines were not assessed.

Conclusion

Our survey of sonologists indicates cine images are widely employed in ultrasound examinations, despite lack of evidence-based guidelines to define optimal utility, although most respondents to this study are from academic centers. A follow-up study to better capture radiologists from other practice settings is warranted to determine if the use of cines is similar across various practice types, whether diagnostic accuracy is improved with cine imaging as a replacement or supplement to static images, and how scanning protocols impact scanning and interpretation time in the context of patient access and radiologist efficiency. Information gained from additional studies will help to further develop and evolve practice parameters and accreditation standards.

References

American College of Radiology® Accreditation Support: Examination Requirements: General Ultrasound (Revised 11-09-2022) https://accreditationsupport.acr.org/support/solutions/articles/11000062867-examination-requirements-general-ultrasound-revised-11-9-2022-. Accessed November 16, 2022.

American College of Radiology® Accreditation Support: Examination Requirements: Gynecological Ultrasound (Revised 01-21-2022). https://accreditationsupport.acr.org/support/solutions/articles/11000062866-examination-requirements-gynecological-ultrasound-revised-1-21-2022-. Accessed November 16, 2022.

American Institute for Ultrasound in Medicine® Practice Parameters. https://www.aium.org/resources/guidelines.aspx. Accessed November 16, 2022.

American Institute for Ultrasound in Medicine® Practice Accreditation. https://www.aium.org/accreditation/accreditation.aspx. Accessed November 16, 2022.

Doust BD, Berland LL. Cine display of numerous static ultrasound images: a step toward automation of ultrasound studies. Radiology 1980. 136:1, 227-228.

Bragg, A, Slaughter, A, Angtuaco, T, From Static Images to Cine Clips: Enhancing the Ultrasound Workflow Environment. Radiological Society of North America 2010 Scientific Assembly and Annual Meeting, November 28 - December 3, 2010, Chicago, IL. http://archive.rsna.org/2010/9010810.html . Accessed January 14, 2023.

Poole PS, Chung R, Lacoursiere Y, Palmieri CR, Hull A, Engelkemier D, Rochelle M, Trivedi N, Pretorius DH. Two-dimensional sonographic cine imaging improves confidence in the initial evaluation of the fetal heart. J Ultrasound Med. 2013 Jun;32(6):963-71. doi: https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.32.6.963. PMID: 23716517.

Scott TE, Jones J, Rosenberg H, Thomson A, Ghandehari H, Rosta N, Jozkow K, Stromer M, Swan H. Increasing the detection rate of congenital heart disease during routine obstetric screening using cine loop sweeps. J Ultrasound Med. 2013 Jun;32(6):973-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.32.6.973. PMID: 23716518.

Gaarder M, Seierstad T, Søreng R, Drolsum A, Begum K, Dormagen JB. Standardized cine-loop documentation in renal ultrasound facilitates skill-mix between radiographer and radiologist. Acta Radiol. 2015 Mar;56(3):368-73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185114527868. Epub 2014 Mar 10. PMID: 24615418.

Dormagen JB, Gaarder M, Drolsum A. Standardized cine-loop documentation in abdominal ultrasound facilitates offline image interpretation. Acta Radiol. 2015 Jan;56(1):3-9. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0284185113517228. Epub 2013 Dec 17. PMID: 24345769.

AIUM Practice Parameter for Documentation of an Ultrasound Examination. J Ultrasound Med 2020; 39: E1–E4. Available at https://www.aium.org/resources/guidelines/documentation.pdf Accessed: Jan. 14, 2023.

ACR – SPR –SRU Practice Parameter for the Performing and Interpreting Diagnostic Ultrasound Examination American College of Radiology Revised 2017. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/US-Perf-Interpret.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2022.

ACR–AIUM–SPR–SRU Practice Parameter for the Performance and Interpretation of Diagnostic Ultrasound of the Thyroid and Extracranial Head and Neck. American College of Radiology Revised 2022. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/ExtracranialHeadandNeck.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2022.

ACR–ACOG–AIUM–SPR–SRU Practice Parameter for the Performance of Ultrasound of the Female Pelvis. American College of Radiology. Revised 2019. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/US-Pelvis.pdf. Accessed December 22, 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Thad Benefield, Statistician, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Radiology for statistical analysis and Dr. Jason Pietryga, Clinical Associate Professor of Radiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for his guidance on study concept

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No disclosures relevant to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Survey questions

-

1

In general, for abnormal/positive findings, does your ultrasound practice rely upon static images only, cine images only, or a combination of static and cine images?

-

o

Static images

-

o

Cine images

-

o

Both static and cine images

-

o

-

2

In general, for normal/negative findings, does your ultrasound practice rely upon static images only, cine images only, or a combination of static and cine images?

-

o

Static images

-

o

Cine images

-

o

Both static and cine images

-

o

-

3

On which of the following organs does your practice always perform cines, even when normal/negative? (Select all that apply)

-

o

Liver

-

o

Kidney

-

o

Gallbladder

-

o

Pancreas

-

o

Common bile duct

-

o

Spleen

-

o

Urinary bladder

-

o

Testicle

-

o

Epididymis

-

o

Uterus

-

o

Ovary

-

o

Adnexa (separate from ovary)

-

o

Thyroid

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

None of above

-

o

-

4

On which of the following organs does your practice perform cines for positive/abnormal findings? (Select all that apply)

-

o

Liver

-

o

Kidney

-

o

Gallbladder

-

o

Pancreas

-

o

Common Bile duct

-

o

Spleen

-

o

Urinary bladder

-

o

Testicle

-

o

Epididymis

-

o

Uterus

-

o

Ovary

-

o

Adnexa (separate from ovary)

-

o

Thyroid

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

None of the above

-

o

-

5

When documenting lesions, does your practice utilize the “split screen” where sagittal and transverse images display on a single image?

-

o

Yes, we use split screen showing both sagittal and transverse view on a single image

-

o

No, we do not utilize the split screen function and keep sagittal and transverse images separate

-

o

We use both separate and split screen

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

Radiologist enters patient room and supervises/performs exam with sonographer in real time. Sonographer performs exam and presents/reviews all cases with radiologist at the workstation or via telecommunication prior to patient discharge

-

o

Sonographer performs exam, discharges patient, and submits images via PACS for interpretation by radiologist

-

o

-

6

Please select which workflow best fits your normal practice

-

o

Hybrid format where radiology enters the room for some, but not all patients

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

None of the above

-

o

-

7

During normal business hours, is a radiologist usually on site with the sonographers at your practice?

-

o

Yes, a radiologist is always present and available to scan in real time

-

o

No, radiologists are usually reading in a different location

-

o

Variable due to multiple imaging sites

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

-

8

How many radiologists interpret ultrasounds in your practice?

-

o

1-10

-

o

11-20

-

o

21-30

-

o

>30

-

o

-

9

Where is your practice located?

-

o

Northeast

-

o

Mid-Atlantic

-

o

Southeast

-

o

Midwest

-

o

Southwest

-

o

West

-

o

Northwest

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

None of the above

-

o

-

10

How would you describe your practice setting?

-

o

Academic

-

o

Private Practice

-

o

Hospital-based employee

-

o

Multi-specialty group employee

-

o

Governmental

-

o

Other (please specify)

-

o

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, K., Burke, L. & McGettigan, M. Use of cine images in standard ultrasound imaging: a survey of sonologists. Abdom Radiol 48, 3530–3536 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-023-04014-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-023-04014-9