Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of the study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of percutaneous drainage for palliation of symptoms and sepsis in patients with cystic or necrotic tumors in the abdomen and pelvis.

Materials and methods

This is a single center retrospective study of 36 patients (18 men, mean age = 51.1 years) who underwent percutaneous drainage for management of cystic or necrotic tumors in the non-postoperative setting over an 11-year period. Nineteen patients with intraabdominal fluid collections associated with primary malignancies included: cervical (n = 7), colorectal (n = 3), urothelial (n = 3), and others (n = 6). The 17 patients with fluid collections associated with intraabdominal metastases stemmed from the following primary malignancies: oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 3), colorectal (n = 3), ovarian (n = 2), lung (n = 2), melanoma (n = 2) along with others (n = 5). Indications for percutaneous drainage were as follows: pain (36/36; 100%); fever and/or leukocytosis (34/36; 94%), and mass effect (21/36; 58%). Seven patients underwent additional sclerosis with absolute alcohol. Criteria for drainage success were temporary or definitive relief of symptoms and sepsis control.

Results

Successful sepsis control was achieved in all patients with sepsis (34/34; 100%) and 30/36 (83%) patients had improvement in pain. Duration of catheterization ranged from 2 to 90 days (mean = 22 days). There were four cases of fluid re-accumulation and one patient developed catheter tract seeding. Alcohol ablation was successful in two patients (2/7; 29%). Nearly all patients (34/36; 94%) died during the follow-up period.

Conclusions

Percutaneous drainage was effective for palliative treatment of symptomatic cystic and necrotic tumors in the majority of patients in this series.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Image-guided percutaneous drainage is the standard of care for many intraabdominal abscesses and other fluid collections, especially in the postoperative setting [1,2,3,4]. The role for percutaneous for fluid collections associated with a primary malignancy or metastasis in the non-postoperative setting is not well defined. Managing infected or cystic abdominal and pelvic tumors with percutaneous drainage can provide palliation for obstruction and pain, providing relief for patients who are poor surgical candidates or undergoing palliative care. Occasionally, an intra-abdominal fluid collection on imaging may be the first presentation of a necrotic or cystic tumor [5, 6].

Percutaneous drainage of postoperative intraabdominal abscesses following tumor resection is a common clinical scenario and has demonstrated its value and efficacy in many large series spanning several decades [7,8,9,10]. However, there are very few case series with a limited number of patients that evaluate percutaneous drainage of fluid collections associated with solid primary malignancies or metastases in the non-postoperative setting [5, 11, 12]. Cystic and necrotic tumors may cause pain, gastrointestinal, biliary or urinary tracts obstruction, with or without becoming infected. In patients who are not operative candidates due to advanced staging or comorbidities may benefit from percutaneous drainage of necrotic or cystic tumors [5, 6]. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and safety of percutaneous drainage for palliation of symptoms and sepsis in symptomatic patients with necrotic or cystic tumors.

Materials and methods

This was an Institutional Review Board approved single center retrospective study over an 11-year period of all patients who underwent percutaneous drainage of necrotic tumors or pathologic fluid collections contiguous and directly associated with an underlying malignancy or metastasis. 36 patients (18 men, 18 women) with a mean age of 51.1 years (range of 17–77 years) met selection criteria. The 36 patients had either primary (n = 19) or metastatic (n = 17) tumors that presented with pain, caused systemic manifestations of infections, or caused obstructive symptomatology.

All fluid collections were located in the abdomen (17/36; 47%) or pelvis 19/36; 53%). The 19 patients with fluid collections associated with a primary malignancy included: cervical cancer (n = 7), colorectal cancer (n = 3), urothelial cancer (n = 3), ovarian (n = 2), liposarcoma (n = 2), along with renal cell carcinoma (n = 1) and anal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 1) (Fig. 1). The 17 patients with fluid collections associated with metastases stemmed from the following primary malignancies: oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (n = 3), colorectal cancer (n = 3), ovarian cancer (n = 2), lung cancer (n = 2), melanoma (n = 2) along with anal, testicular, urothelial, sarcoma, and uterine cancer (n = 1 each) (Fig. 2). Anatomically, 9 metastatic fluid collections were intraabdominal not centered within viscera in the abdomen (n = 6) or pelvis (n = 3). The 8 metastatic lesions centered in solid organs include intrahepatic (n = 6) and two manifested as a pancreatic or splenic collection (n = 1 each).

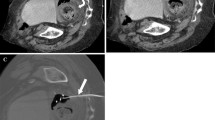

47-year-old female presented with ovarian cancer presented with abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis. CT examination with oral and intravenous contrast showed a rim-enhancing large left lower quadrant fluid collection (a, b). CT-guided percutaneous drainage catheter placement procedural image demonstrates successful placement of a 14-F pigtail catheter (c). After initial catheter removal once the patient developed re-accumulation of the fluid collection that resolved with percutaneous drainage (not pictured). Follow-up CT shows no recurrent collection (d)

41-year-old female with a history of colon cancer presented with abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis. CT showed a rim-enhancing large peripancreatic collection intimately associated with the second portion of the duodenum (a, b). Cytology from the drainage procedure showed malignant cells from gastrointestinal origin in keeping with metastases from the patient’s colon cancer. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage successfully inserted a 14-F pigtail catheter. A follow-up CT examination showed improvement but not resolution of the fluid collection (c, d). The catheter was removed after the drainage decreased to less than 10 ml per day

Indications for percutaneous drainage were pain (n = 36; 100%), fever with leukocytosis (n = 34; 94%), mass effect (n = 21; 58%). The 21 cases of mass effect manifested as gastrointestinal obstruction (n = 12), hydroureteronephrosis (n = 6), lower extremity edema (n = 2), and biliary obstruction (n = 1). Forty-five drainage procedures were performed on lesions that ranged in size from 4 cm to 27 cm in greatest transverse (mean size = 8 cm) diameter using computed tomographic (n = 24), sonographic (n = 16), or combined sonographic and fluoroscopic (n = 5) guidance. All drainage procedures were performed under conscious sedation with midazolam and/or fentanyl and lidocaine for local anesthesia. Catheter size ranged from 7F to 14F, which was determined by fluid collection size and the characteristics of the fluid drained at initial access. If a fluid collection was large, ≥ 6 cm, and purulent or if the fluid drained during the initial percutaneous access contained debris (e.g., enteric content or particles), larger diameter 12F or 14F catheters were used. For cystic fluid collections or purulent collection < 6 cm, a 10.2F catheter was initially used. A catheter exchange with downsizing using smaller diameter catheters (7F or 8.5F) was used for patients with persistent drainage > 10 ml/day and a residual cavity at follow-up sinogram. Follow-up sinogram was routinely scheduled for 7–14 days post-drainage and performed earlier if the patient’s clinical condition did not improve or deteriorated.

Sclerotic therapy with absolute ethanol was selectively used in patients with cystic tumors (n = 7), defined by persistent > 30 ml/day serous or serosanguinous non-viscous drainage output who were not candidates for surgical resection. The sclerotherapy was considered at follow-up sinogram if the characteristic of the drainage output still had a serous or serosanguinous non-viscous appearance and a persistent output of > 30 ml/day, the patient had persistent pain or discomfort, and clinical and laboratory manifestations of sepsis and infection resolved following initial evacuation of the collection and treatment with antibiotics.

Criteria for successful intervention were temporary or definitive control of sepsis as determined by defervescence and/or normalization of leukocytosis, relief of symptoms (pain) and the resolution of the fluid collection. Follow-up of all patients ranged from 2 to 60 months.

Results

Of the 36 patients who presented with pain, 30 (83%) had definitive relief of their symptoms. The volume of drained fluid ranged from 10 ml to 700 ml with a mean volume of 145 ml. All (34/34; 100%) patients with sepsis showed control of infection following percutaneous drainage. Malignant cells were recovered in only 9 (25%) drainage procedures. Ten out of 12 (83%) patients with intestinal obstruction showed relief of symptoms. Four out of the 6 patients (67%) with genitourinary obstruction showed relief of symptoms. Of the 2 patients with lower extremity edema, both showed resolution. The one patient with biliary obstruction had improvement but not resolution in their obstructive jaundice. Multiple catheters were used for drainage of large collections in 5 patients. Duration of catheterization ranged from 2 to 90 days (mean = 22 days). Four patients had an enteric fistula associated with their organized fluid collection (i.e., abscess-fistula complex); one case was due to inadvertent enterotomy during percutaneous catheter manipulations. There were four cases of fluid reaccumulation following catheter removal and two cases catheter occlusion or kink requiring catheter manipulation and replacement. The four recurrences included three tumor-abscesses (intrahepatic collection, intraabdominal abscess associated with colorectal metastasis, and pelvic collection associated with urothelial cancer; n = 1 each) and one cystic collection associated with ovarian cancer. No fluid collections required surgical drainage. Only one patient went on to definitive resection of their tumor (nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma). Complications from percutaneous drainage included enteric fistula development (n = 1) and catheter tract seeding (n = 1; pelvic fluid collection associated with cervical cancer).

Ethanol ablation was attempted in 7 patients with cystic tumors and was successful (no subsequently re-accumulation of fluid) in 2/7 patients (29%). Nearly all patients (34/36; 94%) died during the follow-up period. One patient was alive after surgical resection of renal cell carcinoma at 11-months post resection and the last patient was lost to follow up.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates efficacy and feasibility in using percutaneous drainage to manage intraabdominal necrotic tumors with organized abscesses along with cystic tumors for effective evacuation and pain relief in the majority (30/36; 83%) of patients. The natural history of many primary malignancies and metastases is such that when the growing tumor outgrows its vascular supply, ischemia and necrotic cell death within the tumor mass can result in organized fluid collections. Tumor abscesses and cystic tumors with indications for drainage are uncommon and there are only few prior reported series [5, 11, 12] and uncommon in larger drainage series [7,8,9,10]. Although percutaneous drainage did not affect the patients’ final outcome with the majority of patients expiring during the follow-up period, it did provide a palliative benefit.

Percutaneous drainage is standard management for the majority of fluid collections in the abdomen which are indicated for evacuation [1,2,3,4]. The safety and feasibility of using percutaneous drainage to manage intra-abdominal fluid collections has been corroborated in many series, some with hundred of patients [7,8,9,10]. However, the role for percutaneous drainage for metastases and solid malignancies is less well defined. The 2015 American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria on Percutaneous Catheter Drainage of Infected Fluid Collections comments that percutaneous drainage of infected or fluid-filled tumors may be intentional or inadvertent, the latter if it is the initial presentation of malignancy. The criteria comment that one should evaluate the potential for surgical resection as drainage in these patients may be prolonged or indefinite [1].

There are few small case series with patients presenting with tumor-abscesses/tumor-fluid collections. Our literature search revealed only few series with a focus on fluid collections associated with tumors [5, 11, 12], the largest of which included 16 patients [5]. Additionally, in reviewing larger catheter series, the largest number of patients our literature search revealed was 5 patients in a series of 250 patients [7]. Prior to the present series, Mueller et al. [5] presented the largest published retrospective cohort of tumor abscesses with 16 patients. In that study, the slight predominance of fluid collections associated with a primary malignancy included gynecologic cancers (5 of 9; 56%) compared to 9 of 19 (47%) in the present series. Three patients in that series required surgical drainage, compared to none in the present series. Similar to the Mueller et al. [5] cohort, our patient population suggests successful immediate outcomes post abscess drainage and supports abscess drainage as a palliative measure. Several very small case series were also reported in the literature with specific themes, such as drainage in patients with gynecologic malignancies [11] and drainage for abscess patients with desmoid tumors secondary to Gardner’s syndrome [12].

Our cohort had four cases of tumors-related fistulas during their cancer progression with one fistula caused by percutaneous abscess drainage. These cases had sepsis that resolved post catheter placement and drainage. Percutaneous management of abscess-fistula complexes is an effective treatment that is able to manage such patients either definitively or as a bridge to surgical resection, the latter of which was not needed in the present series [13, 14].

Some limitations of the study include its retrospective nature including available data from medical records. The design of our study only captured patients managed with percutaneous drainage, rather than all patients who presented with tumor fluid collections. Data that present all patients and the proportion of which are managed with percutaneous drainage compared to surgical drainage or resection or with palliative care would better substantiate the role of percutaneous drainage. Furthermore due to patient’s inherent comorbidities and cancer-related mortality, it is difficult to evaluate the long-term benefits of percutaneous drainage in tumor abscess management.

In our series, percutaneous drainage of cystic or necrotic tumors was an effective palliative technique that achieved temporary control of symptoms from the tumors. When used in patients with unresectable tumors with obstructive or septic symptomatology, necrotic tumor percutaneous drainage of necrotic or cystic tumors is a relatively safe and effective procedure. Selective use of sclerotherapy for cystic tumors did not render a consistent benefit to patient outcomes.

References

Lorenz JM, Funaki BS, Ray CE, et al. (2009) ACR Appropriateness Criteria on percutaneous catheter drainage of infected fluid collections. J Am Coll Radiol 6:837–843. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2009.08.011

Wallace MJ, Chin KW, Fletcher TB, et al. (2010) Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous drainage/aspiration of abscess and fluid collections. J Vasc Interv Radiol 21:431–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2009.12.398

vanSonnenberg E, Wittich GR, Goodacre BW, et al. (2001) Percutaneous abscess drainage: update. World J Surg 25:370–372 (discussion 370-372)

Ballard DH, Flanagan ST, Griffen FD (2016) Percutaneous versus open surgical drainage: surgeon’s perspective. J Am Coll Radiol 13:364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2016.01.012

Mueller PR, White EM, Glass-Royal M, et al. (1989) Infected abdominal tumors: percutaneous catheter drainage. Radiology 173:627–629. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.173.3.2479049

Maher MM, Gervais DA, Kalra MK, et al. (2004) The inaccessible or undrainable abscess: how to drain it. Radiographics 24:717–735. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.243035100

vanSonnenberg E, Mueller PR, Ferrucci JT (1984) Percutaneous drainage of 250 abdominal abscesses and fluid collections. Part I: results, failures, and complications. Radiology 151:337–341. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.151.2.6709901

Politano AD, Hranjec T, Rosenberger LH, et al. (2011) Differences in morbidity and mortality with percutaneous versus open surgical drainage of postoperative intra-abdominal infections: a review of 686 cases. Am Surg 77:862–867

Akinci D, Akhan O, Ozmen MN, et al. (2005) Percutaneous drainage of 300 intraperitoneal abscesses with long-term follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 28:744–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00270-004-0281-4

Lambiase RE, Deyoe L, Cronan JJ, Dorfman GS (1992) Percutaneous drainage of 335 consecutive abscesses: results of primary drainage with 1-year follow-up. Radiology 184:167–179. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.184.1.1376932

Ramondetta LM, Dunton CJ, Shapiro MJ, et al. (1996) Percutaneous abscess drainage in gynecologic cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol 62:366–369

Maldjian C, Mitty H, Garten A, Forman W (1995) Abscess formation in desmoid tumors of Gardner’s syndrome and percutaneous drainage: a report of three cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 18:168–171

Ballard DH, Hamidian Jahromi A, Li AY, et al. (2015) Abscess-fistula complexes: a systematic approach for percutaneous catheter management. J Vasc Interv Radiol 26:1363–1367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2015.06.030

Ballard DH, Erickson AM, Ahuja C, et al. (2018) Percutaneous management of enterocutaneous fistulae and abscess-fistula complexes. Dig Dis Interv 02:131–140. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1660452

Funding

No funding was received for this study. Dr. Ballard receives salary support from National Institutes of Health TOP-TIER Grant T32-EB021955.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived by the institutional research committee for this HIPAA compliant retrospective study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ballard, D.H., Mokkarala, M. & D’Agostino, H.B. Percutaneous drainage and management of fluid collections associated with necrotic or cystic tumors in the abdomen and pelvis. Abdom Radiol 44, 1562–1566 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1854-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-018-1854-z