Abstract

Background

With the development and refinement of techniques most mastectomy patients nowadays are candidates for breast reconstruction. No one surgical technique fits all, however. Treatment choices are driven by patient characteristics and preferences, alongside policy and operational factors. These, in turn, might be expected to differ on several levels of aggregation, for example, countries, regions, and hospitals. The aim of this study was to compare choices for breast reconstruction timing and modality in Uppsala (Sweden), Maastricht (the Netherlands), and Rome (Italy).

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, patients presenting for first-time post-mastectomy breast reconstruction in three teaching hospitals were included. The primary study outcomes were breast reconstruction timing and modality. Covariables were body habitus (i.e., body mass index, waist circumference, and mastectomy weight), health-related quality of life assessed with the BREAST-Q Reconstruction module, patient preferences assessed with a self-constructed questionnaire, and shared decision making assessed with the CollaboRATE questionnaire. Statistical tests were used to compare data across study sites.

Results

Sixty-six participants were included. The most common choices for breast reconstruction timing and modality were delayed DIEP flaps in Uppsala (53%), immediate DIEP flaps in Maastricht (44%), and immediate prepectoral implants in Rome (92%). Participants in Rome were much slenderer than participants in Uppsala and Maastricht (mean body mass index 21.6, 26.2, and 26.3 kg/m2, respectively; p < 0.05). Participants in Uppsala and Maastricht highly valued material used for the reconstruction; participants in Rome were significantly more concerned with complications, scars, and recovery duration associated with the reconstruction.

Conclusions

This study shows large differences in choices for breast reconstruction timing and modality in Uppsala, Maastricht, and Rome. Possible reasons for the observed variation include differences in patient characteristics, patient preferences, reconstructive techniques available, and reimbursement.

Level of evidence

Level IV, Therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2020, more than 531000 women in Europe were diagnosed with breast cancer [1]. In the same year, more than 156000 mastectomies were performed in Europe [2]. Prompted by potential quality of life benefits [3, 4], current guidelines stipulate that all women undergoing mastectomy be offered breast reconstruction [5,6,7].

With the development and refinement of techniques [8], most mastectomy patients nowadays are candidates for breast reconstruction. No one surgical technique fits all, however. Treatment choices are driven by patient characteristics and preferences, alongside policy and operational factors. These, in turn, might be expected to differ on several levels of aggregation, for example, countries, regions, and hospitals [9,10,11]. A previous study reported substantial geographic variation in five US states [12], yet treatment patterns across European countries have not been mapped.

The aim of this study was to compare breast reconstruction timing and modality across three teaching hospitals in high-income countries with remarkably distinctive cultures and healthcare systems: Sweden, the Netherlands, and Italy. To interpret results, we also compared case mix, patient preferences, and patient involvement in the decision-making process across study sites.

Methods

Study design and participants

We performed an observational cross-sectional study at three teaching hospitals (i.e., Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden; Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands; University Hospital Agostino Gemelli, Rome, Italy). We included consecutive patients presenting for first-time post-mastectomy breast reconstruction in February 2020 (Uppsala), between October and December 2021 (Rome), and between January and April 2022 (Maastricht). Patients presenting for repeat reconstruction, mastectomy scar revision, and those with partial mastectomy defects were excluded. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from all participating hospitals. All participants gave informed consent in accord with the ethical standards of the 1975 Helsinki Declaration [13].

Setting

The participating hospitals’ breast units each treat over 500 breast cancer patients per year. Patients who require or choose mastectomy are referred to a reconstructive surgeon, who elicits their values, expectations, and concerns. The surgeon proposes medically relevant reconstructive options (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows contraindications) and discusses associated pre-operative, intra-operative, and postoperative aspects, including complications, recovery, scarring, and secondary procedures. Patients are given time to consider options and can request a second consultation if desired. Patients do not pay out of pocket in any of the three countries: in Sweden and the Netherlands, health insurance covers post-mastectomy breast reconstruction; in Italy, health insurance covers delayed reconstruction, and the hospital pays for immediate reconstruction.

Data collection

Participants were recruited during outpatient breast reconstruction consultations. Self-reported height and weight were recorded. Waist circumference was tape-measured at the midpoint between the lower margin of the least palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest [14]. Participants were asked to complete a pseudonymized paper-based questionnaire comprising socio-demographic questions (i.e., educational level, employment status, marital status, and smoking status), the BREAST-Q Version 2.0 Reconstruction Module, the Decision-making Values for Breast Reconstruction questionnaire, and the CollaboRATE questionnaire.

The BREAST-Q Version 2.0 Reconstruction Module is a valid and reliable measure of health-related quality of life in breast reconstruction patients [15, 16]. We used a local Swedish translation and professional Dutch and Italian translations of the following preoperative scales: Satisfaction with breasts, Psychosocial well-being, and Sexual well-being. For each scale, items are summed and transformed on a 0 to 100 scale, with greater values indicating higher levels of health-related quality of life.

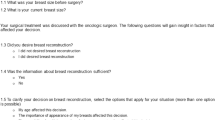

We constructed a Decision-making Values for Breast Reconstruction questionnaire to explore which factors matter to participants in deciding on breast reconstruction timing and modality (see table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows the questionnaire). The questionnaire comprises 13 standalone items rated on a 10-point numeric rating scale, ranging from 1 (‘not important’), to 10 (‘very important’). Item content was informed by clinician experience. The questionnaire was not pretested, and its validity and reliability are unknown. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into Swedish, Dutch, and Italian by authors fluent in these languages.

The CollaboRATE is a valid and reliable measure of shared decision making from the patient perspective [17, 18]. It comprises three items rated on a 9-point numeric rating scale, ranging from 1 (‘no effort was made’), to 9 (‘every effort was made’). Encounters are coded as either '1', if the response to all items is 9, or '0' if the response to any of the items is less than 9. The final score equals the percentage of encounters coded as '1'; higher scores represent more shared decision making. We used Swedish and Dutch translations available from the CollaboRATE website. The questionnaire was translated from English into Italian by an author fluent in both languages.

Participant characteristics, including medical history and mastectomy weight, were abstracted from medical records.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were breast reconstruction timing and modality. Timing was categorized as immediate (i.e., at the same time as mastectomy) and delayed. Breast reconstruction modality was categorized as implant-based, tissue-based (i.e., using a free or pedicled flap, or autologous fat transfer [AFT] [19]), and combination procedures. Covariables were body mass index (BMI) as a measure of overall adiposity, waist circumference as a measure of total abdominal fat [20], mastectomy weight as a measure of breast size, health-related quality of life assessed with the BREAST-Q Reconstruction module, patient preferences assessed with the Decision-making Values for Breast Reconstruction questionnaire, and shared decision making assessed with the CollaboRATE questionnaire. Study site (i.e., Uppsala, Maastricht, Rome) was the independent variable of interest.

Data analysis

No sample size based on statistical power was calculated because this study is not hypothesis-driven. Continuous variables are presented as mean (standard deviation), or median (25th-75th percentiles); categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Outcome groups were compared using one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test, or by Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Missing data were excluded from analyses. Data were analyzed using R version 4.0.5 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with α = 0.05 unless otherwise stated.

Reporting

Study methods and results are reported as recommended in the Strengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement [21].

Results

Participant characteristics and case mix

We included 66 participants: 19 in Uppsala, 22 in Maastricht, and 25 in Rome (Fig. 1). In Uppsala, most participants presented for breast reconstruction after completion of mastectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy, whereas in Rome, most participants were newly diagnosed with breast cancer and presented prior to mastectomy (Table 1). Most patients in Uppsala had or were planned for modified radical mastectomy, most participants in Maastricht were planned for skin-sparing mastectomy, and most participants in Rome were planned for nipple-sparing mastectomy. Relative to participants in Uppsala and Rome, participants in Maastricht more often had prophylactic mastectomy. None of the included participants’ health status precluded reconstructive breast surgery; those who smoked agreed to stop at least six weeks before surgery.

Breast reconstruction timing and modality

In Uppsala, four of 19 participants (21%) decided to forgo breast reconstruction (Table 2); they were 29, 37, 51, and 53 years old. Of 15 participants who opted for breast reconstruction, 10 (67%) chose a delayed DIEP flap, six of whom had prior radiotherapy. Two participants with little excess abdominal tissue (BMI 21 and 23 kg/m2; waist circumference 72 and 72 cm) chose implant-based reconstruction. In Maastricht, nine of 22 participants (44%) chose immediate unipedicled or bipedicled DIEP breast reconstruction. Two participants who presented before mastectomy chose a delayed DIEP flap as they would likely require adjuvant radiotherapy. Another participant with unilateral modified radical mastectomy was planned for contralateral prophylactic mastectomy; for optimal left–right symmetry, she chose to have contralateral mastectomy first, followed by bilateral delayed DIEP flaps as a separate procedure. Six participants with insufficient excess abdominal tissue (BMI 21–28 kg/m2; waist circumference 74–88 cm) chose non-abdomen-based reconstructions: three chose immediate unilateral or bilateral diagonal upper gracilis (DUG) flaps, one participant chose bilateral secondary expander/implant-based reconstruction, one participant with prior mastectomy and radiotherapy chose a latissimus dorsi flap with implant, and one participant who sought delayed tissue-based reconstruction but had no adequate perforators in the lumbar, medial thigh, and lateral thigh regions chose breast reconstruction using AFT. In Rome, 24 of 25 participants (92%) chose immediate direct-to-implant breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing (n = 21) or skin-sparing mastectomy (n = 3). One participant with bra cup A in whom the tumor infiltrated the breast skin chose latissimus dorsi flap breast reconstruction. Another participant with prior unilateral modified radical mastectomy and radiotherapy chose a delayed DIEP flap, combined with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy and an immediate DIEP flap.

Body habitus

Height, weight, BMI, and waist circumference did not differ significantly between participants in Uppsala and Maastricht (Fig. 2). Participants in Rome, however, were on average 6 cm shorter, 19 kg lighter, and had a 15 cm smaller waist circumference than participants in Uppsala. Variability in weight, BMI, and waist circumference was much smaller in Rome than in Uppsala and Maastricht. One participant in Rome had a BMI just above 25 kg/m2, whereas 12 participants in Uppsala (63%) and 12 patients in Maastricht (55%) were overweight or obese. Thirteen participants in Uppsala (68%), 14 participants in Maastricht (64%), and 5 participants in Rome (20%) had a waist circumference of 80 cm or more, indicating excess abdominal fat. [14] Mastectomy weight of participants in Maastricht was significantly higher than that of participants in Rome (Fig. 3).

(A) Body height, (B) body weight, (C) BMI, and (D) waist circumference, per study site. Crossbars represent medians. The blue shaded areas represent abnormal ranges for body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference according to the WHO Standard Classification of Obesity [22]. * p < 0.05. See table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which provides numerical data

Mastectomy weight, per study site. Crossbars represent medians. For bilateral mastectomies, mean mastectomy weight of the two specimen was calculated. * p < 0.05. See table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which provides numerical data

Questionnaire scores

Fifty-two participants returned the questionnaires (79% response rate; Fig. 1). Participants in Rome scored on average 11 points higher on psychosocial wellbeing and 15 points higher on sexual wellbeing than participants in Uppsala (Table 3). Participants in Maastricht were most satisfied with their breasts. None of the differences in BREAST-Q scores were statistically significant. Uppsala and Maastricht produced roughly similar response patterns to the Decision-making Values for Breast Reconstruction questionnaire, with ‘material used for reconstruction’ being most highly valued (Fig. 4). Participants in Rome often used higher response categories than those in Uppsala and Maastricht. They were significantly more concerned with complications, scars, and recovery duration associated with the reconstruction, and cared more about keeping their own nipple. Surgeons were participants’ most important counsellors, although participants in Rome attached significantly greater importance to their surgeon’s opinion than participants in Maastricht. The percentage of participants who experienced gold standard shared decision making as evaluated with the CollaboRATE questionnaire was highest in Maastricht (10 of 21 participants [48%]), followed by Rome (6 of 13 participants [46%]), and Uppsala (7 of 18 participants [39%]). These differences were not statistically significant. The four participants in Uppsala who chose to forgo breast reconstruction experienced high degrees of shared decision making, with total CollaboRATE scores ranging from 25 to 27 out of 27.

Decision-making values, by study site. Decision-making values as evaluated with the Decision-making Values for Breast Reconstruction questionnaire. Items were rated on a 10-point numeric rating scale, ranging from 1 (‘not important’), to 10 (‘very important’). X-axes represent percent of respondents; in calculating percentages, participants who did not respond to a question were excluded. See table, Supplemental Digital Content 4, which provides numerical data

Discussion

We found substantial variation in choices for breast reconstruction timing and modality across study sites: the most prevalent choices were delayed DIEP flaps in Uppsala (53%), immediate DIEP flaps in Maastricht (44%), and immediate prepectoral implants in Rome (92%). The Maastricht cohort represented the broadest range of reconstructive techniques. Possible reasons for the observed variation include differences in patient characteristics, patient preferences, reconstructive techniques available, and reimbursement.

Patient characteristics and anti-cancer treatments constrain the decision tree for breast reconstruction. Therefore, case mix differences between study sites necessarily translated into differences in breast reconstruction patterns. In most participants in Uppsala, prior mastectomy and radiotherapy precluded immediate and implant-based reconstruction. In Maastricht and Rome, most participants presented before mastectomy, unlocking the option of immediate reconstruction. For aesthetic reasons, implant-based reconstruction offered a poor choice for overweight and obese participants in Uppsala and Maastricht [23], whilst in Rome, participants’ slender posture often suspended their eligibility for tissue-based reconstruction.

Patient preferences also varied between study sites. Participants in Uppsala and Maastricht highly valued material used for reconstruction and often chose tissue-based procedures. Conversely, participants in Rome prioritized complications, scars, and recovery duration, which may align better with implant-based reconstruction.

DUG flaps, AFT, and bipedicled DIEP flaps were unique to the Maastricht cohort; the former two methods were not offered in Uppsala and Rome at the time of study, and the latter only in exceptional cases. Although patients arguably require more guidance when choosing among a larger pool of treatment options, our data suggest the opposite, for participants in Maastricht attached lower importance to their surgeon’s opinion than those in Uppsala and Rome. Patients skeptical about expert opinion potentially seek more personalized treatment [24], which might have created a demand for the range of reconstructive options offered in Maastricht. In Rome, implants are routinely placed in the prepectoral space if the mastectomy flap is sufficiently thick and adequately perfused [25]; in Uppsala and Maastricht, implants are routinely placed in the submuscular space. Prepectoral placement might elevate the acceptance and endorsement of implant-based breast reconstruction, as adverse outcomes associated with submuscular placement are largely avoided [25]. In addition, reimbursement for immediate breast reconstruction in Italy is included in the price for mastectomy. This price falls short of the surgery’s true cost, forcing surgeons to direct treatment choice towards the least expensive method.

Breast reconstruction timing and modality patterns reported in this study are not generalizable beyond hospital level. Immediate breast reconstruction rates in Sweden and the Netherlands vary markedly by region due to hospital organizational factors [26, 27], such that data collected from Uppsala and Maastricht reveal little about national patterns. In 2009–2014, two-stage implant-based procedures were the most common type of breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy in Italy, whereas in our Rome cohort, participants opting for implant-based reconstruction were all scheduled for a one-stage procedure [28]. Uppsala and Maastricht are referral centers for autologous breast reconstruction, and as such, autologous reconstruction rates far exceed the nationwide average [26, 27]. The large share of bilateral reconstructions in Maastricht partially stems from outsourcing of unilateral breast reconstructions to community hospitals. Follow-up studies aiming to compare breast reconstruction patterns across countries should include a representative sample of hospitals in each country [29].

Gold standard shared decision making was achieved in 39–48% of cases. These percentages loosely approximate to 43% of participants making a high-quality decision for breast reconstruction as reported in a prior study [30]. Patients who engage in shared decision making tend to report higher satisfaction with postoperative outcomes and experience less decisional regret [31, 32]. Decision aids could be helpful tools for increasing gold standard shared decision-making rates [33].

A potential study limitation is bias induced by differences in response styles. In 2006, Harzing showed major between-country differences regarding the tendency to use certain response categories on ratings scales regardless of content [34]. Differences in response patterns to the self-constructed Decision-making Values for Breast Reconstruction questionnaire resemble Harzing’s findings (i.e., a tendency to use extreme response categories in Sweden, a tendency to use middle response categories in the Netherlands, and a preference for extreme responses towards the positive end in Southern European countries). International response bias might equally have distorted BREAST-Q and CollaboRATE scores, as their validity for cross-country comparisons outside Northern America have not been established. If we are to understand patients’ decision-making values for breast reconstruction as well as their psychological bases, a qualitative approach would seem the appropriate format to eliminate limitations of international questionnaire research. In addition, cultural settings that shape breast reconstruction patterns could be further explored in a sociological study.

Conclusions

We identified wide variability in choices for breast reconstruction timing and modality across Uppsala, Maastricht, and Rome. Tissue-based procedures were the most common choice in Uppsala and Maastricht, and implant-based procedures were most common in Rome. These patterns coincided with corresponding differences in patient body habitus and preferences. Our results illustrate that there is no holy grail in breast reconstruction timing and modality, as patient characteristics and preferences, reconstructive options available, and health care opportunities and constraints vary along with (geographical) context. Despite its limitations, this study serves to highlight that much can be learned from evaluating breast reconstruction patterns in other places where different norms might prevail—because without comparing, we do not see.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author, S.M.H.T. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

Ferlay J et al (2020) Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Available from: gco.iarc.fr/today. Accessed 2 Nov 2022

OECD Health Statistics (2022) Health care utilisation: surgical procedures. Available from: stats.oecd.org. Accessed 13 Dec 2022

Sisco M et al (2015) The quality-of-life benefits of breast reconstruction do not diminish with age. J Surg Oncol 111(6):663–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23864

Atisha D et al (2008) Prospective analysis of long-term psychosocial outcomes in breast reconstruction: two-year postoperative results from the Michigan Breast Reconstruction Outcomes Study. Ann Surg 247(6):1019–28. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181728a5c

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on cancer services. Improving outcomes in breast cancer. Manual update. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/csg1/resources/improving-outcomes-in-breast-cancer-update-pdf-773371117. Accessed 14 Dec 2022

2012, N. Breast Cancer Guideline. Available from: https://www.lrcb.nl/resources/uploads/2017/02/Dutch-Breast-Cancer-Guideline-2012.pdf

Cardoso F et al (2019) Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 30(10):1674. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdz189

Homsy A et al (2018) Breast Reconstruction: A Century of Controversies and Progress. Ann Plast Surg 80(4):457–463. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000001312

Stamuli E et al (2022) Patient preferences for breast cancer treatments: a discrete choice experiment in France, Ireland, Poland and Spain. Future Oncol 18(9):1115–1132. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon-2021-0635

McPherson K et al (1981) Regional variations in the use of common surgical procedures: within and between England and Wales, Canada and the United States of America. Soc Sci Med A. 15(3 Pt 1):273–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-7123(81)90011-0

Wennberg J, Gittelsohn A (1982) Variations in medical care among small areas. Sci Am 246(4):120–34. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0482-120

Anderson SR et al (2019) Geographic variation in breast reconstruction modality use among women undergoing mastectomy. Ann Plast Surg 82(4):382–385. https://doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0000000000001746

Rickham, PP (1964) Human experimentation. Code of ethics of the world medical association. Declaration of Helsinki. Br Med J 2(5402): 177. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.5402.177

Waist circumference and waist-hip ratio (2011) report of a WHO expert consultation, Geneva, 8–11, December 2008. World Health Organization, Geneva (CH)

Pusic AL et al (2009) Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg 124(2):345–353. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807

Davies CF et al (2021) Patient-reported outcome measures for post-mastectomy breast reconstruction: A systematic review of development and measurement properties. Ann Surg Oncol 28(1):386–404. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-08736-8

Elwyn G et al (2013) Developing CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of shared decision making in clinical encounters. Patient Educ Couns 93(1):102–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.05.009

Barr PJ et al (2014) The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: a fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process. J Med Internet Res 16(1):e2. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3085

Schop SSJ et al (2021) BREAST trial study protocol: evaluation of a non-invasive technique for breast reconstruction in a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 11(9):e051413. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051413

Clasey JL et al (1999) The use of anthropometric and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) measures to estimate total abdominal and abdominal visceral fat in men and women. Obes Res 7(3):256–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00404.x

Vandenbroucke JP et al (2007) Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 18(6):805–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181577511

WHO (2000) Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic, Report of a WHO Consultation on Obesity, Technical Report Series No. 894. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland. p 256

Atisha DM et al (2008) The impact of obesity on patient satisfaction with breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg 121(6):1893–1899. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181715198

Iliffe S, Manthorpe J (2020) Medical consumerism and the modern patient: successful ageing, self-management and the “fantastic prosumer”. J R Soc Med 113(9):339–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076820911574

Salgarello M et al (2021) Direct to Implant Breast Reconstruction With Prepectoral Micropolyurethane Foam-Coated Implant: Analysis of Patient Satisfaction. Clin Breast Cancer 21(4):e454–e461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clbc.2021.01.015

Unukovych D et al (2020) Breast reconstruction patterns from a Swedish nation-wide survey. Eur J Surg Oncol 46(10 Pt A):1867–1873. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2020.04.030

van Bommel AC et al (2017) Large variation between hospitals in immediate breast reconstruction rates after mastectomy for breast cancer in the Netherlands. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 70(2):215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2016.10.022

Casella D et al (2017) Current trends and outcomes of breast reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy: results from a national multicentric registry with 1006 cases over a 6-year period. Breast Cancer 24(3):451–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-016-0726-z

van Hoeven LR et al (2015) Aiming for a representative sample: Simulating random versus purposive strategies for hospital selection. BMC Med Res Methodol 15:90. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-015-0089-8

Lee CN et al (2017) Quality of Patient Decisions About Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy. JAMA Surg 152(8):741–748. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0977

Ashraf AA et al (2013) Patient involvement in the decision-making process improves satisfaction and quality of life in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. J Surg Res 184(1):665–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2013.04.057

Sheehan J et al (2008) Regret associated with the decision for breast reconstruction: the association of negative body image, distress and surgery characteristics with decision regret. Psychol Health 23(2):207–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/14768320601124899

Berlin NL et al (2019) Feasibility and Efficacy of Decision Aids to Improve Decision Making for Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med Decis Making 39(1):5–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X18803879

Harzing A-W (2006) Response styles in cross-national survey research: A 26-country study. Int J Cross Cult Manage 6(2):243–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595806066332

Acknowledgements

We thank Bjorn Jennekens and Anna Nilsson for their help with data collection. This work was supported by travel grants from Erasmus+, and from GROW—School for Oncology and Developmental Biology, Maastricht University Medical Center.

Funding

This work was supported by travel grants from Erasmus + , and from GROW—School for Oncology and Developmental Biology, Maastricht University Medical Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

This is an observational study. The Institutional Review Board of all three participating hospitals have confirmed that no ethical approval is required.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Additional informed consent was obtained from all individual participants for whom identifying information is included in this article.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Smeele, H.P., Bijkerk, E., van Rooij, J.A.F. et al. Breast reconstruction timing and modality in context: A cross-sectional study in Uppsala, Maastricht, and Rome. Eur J Plast Surg 47, 2 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-023-02146-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00238-023-02146-1