Abstract

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant condition clinically presenting with heterogenous clinical features. Multiple neuroradiological manifestations have been associated with TSC, such as tubers, radial migration lines, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, and cyst-like lesions of the white matter (CLLWMs). The latter have been described as non-enhancing well-defined cysts whose pathogenesis is still unknown. We describe 2 TSC patients with CLLWM showing contrast enhancement after Gadolinium injection, a previously unreported entity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC, MIM 605284) is an autosomal dominant condition with an estimated prevalence of 1:600–1:10,000 [1]. It is caused by the mutation of TSC1 and TSC2, two genes involved in cell growth regulation, with TSC2 mutations being more frequent and are associated with a more severe phenotype.

Neuroradiological manifestations include tubers, radial migration lines, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, and cyst-like lesions of the white matter (CLLWMs) [2]. The latter occur in 15–44% of TSC patients have been described as well-defined cysts whose content is isointense to the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) without contrast enhancement [3].

We describe 2 TSC patients with CLLWMs showing contrast enhancement. To the best of our knowledge, no other contrast-enhancing CLLWMs have been reported so far.

Case series

Patient 1

This 13-year-old girl undergoes brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) follow-up due to genetically confirmed TSC (de novo heterozygous mutation NM_000548.5(TSC2):c.2639+1G>C falling in the splice donor site of intron 22). Neurologically, she presented with intellectual delay and epilepsy.

A CLLWM was present since her first brain MRI, which was performed at the age of 6.

It was located in the white matter near the frontal horn of right lateral ventricle. It appeared as a cluster of cysts with sharp boundaries and a content isointense to the CSF. It was surrounded by a thin rim of brain tissue isointense to the gray matter in all sequences and in DWI/ADC. Intense and homogeneous peripheral contrast enhancement was evident.

From the first brain MRI up to the last one (which was performed at the age of 12), the morphological features, signal, and contrast enhancement characteristics of the CLLWM have not changed. On the other hand, its dimensions have slightly decreased (from 11×5mm to 8×4mm) (Fig. 1).

Axial T2 (a) and FLAIR with fat saturation (b), axial T1 without (c), and with contrast injection (d) showing a CLLWM (arrows in a–d) in the first TSC patient. An incomplete peripheral halo isointense to the cortex in all sequences (white arrowheads in a–c) shows intense contrast enhancement (white arrowheads in d)

Multiple supratentorial cortical tubers and subependymal nodules, one subependymal giant cell astrocytoma were present.

Patient 2

This 12-year-old boy with epilepsy undergoes annual brain MRI follow-up because of genetically confirmed TSC (de novo heterozygous mutation NM_000548.5(TSC2):c.1839+1G>A affecting the splice donor site of intron 17).

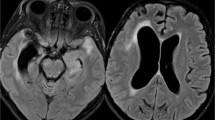

A CLLWM near the body of the left lateral ventricle was present since his first brain MRI performed at the age of 9 (Fig. 2). It had a multi-cystic appearance and a fluid content isointense to the CSF. It was surrounded by white matter of regular signal intensity and only few of its internal septa showed intense contrast enhancement.

Axial T2 (a) and FLAIR with fat saturation (b), axial T1 without (c), and with fat saturation after contrast injection (d) show a multi-cystic CLLWM (arrows in a–d) in the second TSC patient. It is surrounded by white matter of regular signal intensity and only few of its internal septa have intense contrast enhancement

Its morphological features, signal, and contrast enhancement characteristics have not changed since the first MRI up to the last one, which was performed at the age of 12. Its dimensions have slightly increased, going from 10×7mm to 12×9mm in 3 years.

Other findings were multiple cortical tubers and subependymal nodules and supratentorial hydrocephalus caused by a subependymal giant cell astrocytoma surgically removed at the age of 9.

Discussion

CLLWMs have already been reported in TSC [3,4,5,6]. Van Tassel et al. were the first to extensively describe them [4]. They reported the CLLWMs as well-defined, round, or oval cystic formations in periventricular location, with a content isointense to CSF, dimension ranging from 2 to 12 mm and without contrast enhancement.

Their pathogenesis is still unknown and it has been hypothesized that they might be the result of white matter degeneration, cerebral infarction, or dilatation of Virchow-Robin spaces [6]. A cerebral infarction origin seems unlikely as CLLWMs does not have the imaging features of ischemic areas. The dilation of Virchow-Robin spaces is an incidental finding. They are usually surrounded by gliosis and are located in the basal ganglia, periventricular white matter, midbrain, and in the subcortical white matter of the anterior-superior temporal lobes [7]. They have sharp boundaries, a fluid content isointense to CSF, and do not show contrast enhancement. Therefore, the enhancing CLLWMs described in this report are unlikely to represent simple dilated Virchow-Robin spaces. Furthermore, we exclude the presence of vascular structures in the enhancing tissue of the CLLWMs as susceptibility weighted sequences have been performed in both cases and one patient also underwent dynamic susceptibility contrast perfusion-MR and they did not show the presence of vessels displaced by the CLLWMs or within their septa. Plus, there was no delay between injection and imaging in both cases. A blood-brain barrier alteration with increased permeability, already described in TSC cortical tubers, could explain peripheral contrast enhancement we observed. This would also lead to persistent and complex activation of inflammatory pathways with inflammatory cell infiltration [8]. Furthermore, blood-brain barrier alterations determining this neuroradiological finding would explain the absence of significant modifications to the follow-up.

Other cystic brain lesions may be present in TSC patients. For instance, cortical tubers may undergo cystic degeneration and show contrast enhancement in 10% of cases [9]. CLLWMs are a distinct entity and are not related to cystic degeneration.

Incidental neuro-epithelial cysts may be present in TSC. They are ovoidal and generally unilocular cystic lesions of ependymal origin with sharp margins. They do not show contrast enhancement and may have different locations.

Glial tumors may develop in TSC patients. Juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma (JPA) is a low-grade tumor which frequently has the appearance of a cystic lesion with a contrast-enhancing mural nodule [10]. In our cases, the diagnosis of JPA was excluded due to the absence of mural nodules and stability over time. High-grade gliomas are rare in children, have a mixed necrotic and solid structure, restricted diffusion, and significantly grow over time. Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumors (DNETs) are rare and usually benign supratentorial tumors typical of the childhood and associated with intractable focal epilepsy. They have a “bubbly” appearance, with contrast enhancement in 20–30% of cases. Their cortical-subcortical location does not correlate with the position in the deep white matter of our enhancing CLLWMs.

Conclusion

CLLWMs have already been described in TSC, but our patients are the first reported to show contrast enhancement. Enhancing CLLWMs might be considered as a novel neuroimaging entity in TSC patients. More cases are necessary to better delineate their neuroradiological characteristics and evaluate their clinical behavior.

Abbreviations

- TSC:

-

Tuberous sclerosis complex

- CLLWM:

-

Cyst-like lesions of the white matter

- CSF:

-

Cerebro-spinal fluid

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- JPA:

-

Juvenile pilocytic astrocytoma

- DNET:

-

Dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor

References

Kingswood JC, Crawford P, Johnson SR, Sampson JR, Shepherd C, Demuth D, Erhard C, Nasuti P, Patel K, Myland M, Pinnegar A, Magestro M, Gray E (2016) The economic burden of tuberous sclerosis complex in the UK: a retrospective cohort study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Med Econ 19:1087–1098. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2016.1199432

Kalantari BN, Salamon N (2008) Neuroimaging of tuberous sclerosis: spectrum of pathologic findings and frontiers in imaging. Am J Roentgenol 190:W304–W309. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.07.2928

Umeoka S, Koyama T, Miki Y, Akai M, Tsutsui K, Togashi K (2008) Pictorial review of tuberous sclerosis in various organs. RadioGraphics. 28:e32. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.e32

Van Tassel P, Curé JK, Holden KR (1997) Cystlike white matter lesions in tuberous sclerosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 18:1367–1373. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9282871

Griffiths PD, Bolton P, Verity C (1998) White matter abnormalities in tuberous sclerosis complex. Acta Radiol 39:482–486. https://doi.org/10.3109/02841859809172211

Rott H-D, Lemcke B, Zenker M, Huk W, Horst J, Mayer K (2002) Cyst-like cerebral lesions in tuberous sclerosis. Am J Med Genet 111:435–439. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.10637

Kwee RM, Kwee TC (2007) Virchow-Robin spaces at mr imaging. RadioGraphics. 27:1071–1086. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.274065722

Boer K, Jansen F, Nellist M, Redeker S, van den Ouweland AMW, Spliet WGM, van Nieuwenhuizen O, Troost D, Crino PB, Aronica E (2008) Inflammatory processes in cortical tubers and subependymal giant cell tumors of tuberous sclerosis complex. Epilepsy Res 78:7–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2007.10.002

Evans JC, Curtis J (2000) The radiological appearances of tuberous sclerosis. Br J Radiol 73:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.73.865.10721329

Collins VP, Jones DTW, Giannini C (2015) Pilocytic astrocytoma: pathology, molecular mechanisms and markers. Acta Neuropathol 129:775–788. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-015-1410-7

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

• Conceptualization: Alessandra D’Amico

• Methodology: Alessandra D’Amico, Carmela Russo

• Data curation: Alessandra D’Amico, Carmela Russo, Lorenzo Ugga, Daniela Melis, Claudia Santoro, Giulio Piluso

• Writing—original draft preparation: Teresa Perillo

• writing—review and editing: Alessandra D’Amico, Lorenzo Ugga, Teresa Perillo

• supervision: Alessandra D’Amico, Giuseppe Cinalli

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Amico, A., Perillo, T., Russo, C. et al. Enhancing cyst-like lesions of the white matter in tuberous sclerosis complex: a novel neuroradiological finding. Neuroradiology 63, 971–974 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-021-02647-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00234-021-02647-5