Abstract

Background

The hepatotoxicity of acetaminophen is recognised worldwide. Unfavourable prognoses relating to overdose include liver transplantation and/or death. Several hepatotoxicity risk factors (HRFs) should motivate the adjustment of acetaminophen daily intake (to < 4 g/day): advanced age, weight < 50 kg, malnutrition, chronic alcoholism, chronic hepatitis B and C and HIV infection, severe chronic renal failure and hepatocellular insufficiency.

Method

Over a 7-day period in Rennes University Hospital in December 2017, using DxCare® software, with an odds ratio estimation, we analysed all acetaminophen prescriptions, to assess to what extent the presence of HRFs altered the prescribers’ choice of acetaminophen dose (< 4 g/day versus 4 g/day).

Results

Among 1842 patients, considering only the first acetaminophen prescription, 73.7% were on 4 g/day. Almost half this population had at least 1 HRF. Whereas around 80% of the prescriptions in the < 4 g/day group were for patients with at least 1 HFR, only 53% of the prescriptions in the 4 g/day group concerned patients without HFRs (p < 0.001). Age > 75 and low weight were associated with the prescriber’s choice of dose. Neither chronic alcoholism nor hepatocellular insufficiency influenced the acetaminophen doses prescribed.

Conclusion

Considering the widespread use of acetaminophen and its favourable safety profile compared with other analgesic drugs, it appears urgent to remind prescribers of the maximum daily dose recommendations for acetaminophen for patients with HRFs, especially those with chronic alcoholism and hepatocellular insufficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acetaminophen, also known as “paracetamol”, is the most widely prescribed first-line analgesic worldwide. Available as an over-the-counter drug in many countries such as France or the USA, it appears as the most frequent medication involved in both intentional and unintentional drug poisoning, according to the annual report by the American Association of Poison Control Center Data System and the French Addiction Monitoring Network [1, 2].

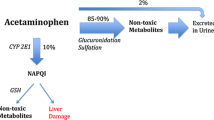

In case of acetaminophen accumulation and overdose, the main expected adverse effect is acute liver failure, including fulminant hepatitis, which can lead to liver transplantation and/or death [1, 3,4,5]. The hepatotoxicity mechanism involves a CYP 450 (mainly 2E1) highly reactive converted metabolite, namely N-acetyl p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI). NAPQI is physiologically broken down by glutathione in the liver and excreted in the urine. However, in case of acetaminophen overdose, NAPQI production increases and exceeds the conjugation abilities of glutathione; as it binds to the hepatocellular membrane proteins, it induces liver parenchymal cell death [6].

For a mean adult weight, clinical symptomatic acetaminophen hepatotoxicity is usually expected after a single acetaminophen ingestion of around 10 g per 24 h or 150 mg/kg, with an initial phase of cytolysis occurring in the first 24 to 48 h. The hepatotoxicity is dose-dependent and can be predicted by a nomogram [7]. Immediately after an acetaminophen overdose, N-acetylcysteine is used to restore glutathione reserves which can limit hepatotoxicity [8] with recovery expected in 4–5 days where the prognosis is favourable [9]. Studies have shown that advanced age and chronic alcohol consumption, as well as fasting/anorexia and poor nutritional status, could be associated with glutathione depletion; it is worth noting that chronic alcohol consumption has also been shown to be a CYP 2E1 inducer leading to NAPQI increase [10,11,12]. Chronic renal failure and chronic liver disease (hepatic failure, cirrhosis, viral hepatitis) are also considered to be acetaminophen hepatotoxicity risk factors (HRFs) [13,14,15,16] and should lead to an adjustment of acetaminophen daily intake. Meanwhile, case reports of hepatitis observed at therapeutic doses of 3 or 4 g/day have been reported among patients with low weight, a history of chronic alcoholism, hepatic steatosis or recent fasting [17,18,19,20,21]. Furthermore, certain randomised controlled trials have reported an increase (mostly 3 to 4 times the normal upper limit) in serum alanine aminotransferase activity (ALT) for a significant proportion of “healthy” patients exposed to acetaminophen at 4 g/day for several days, compared with placebo [22, 23], although the clinical significance is uncertain.

Recommendations have been established for acetaminophen prescription, with a maximum daily dose of 4 g, and they include dose adjustment for patients with HRFs [24,25,26]. Dose adjustments are detailed in most summary of product characteristics (SmPC) for acetaminophen-based medications. A lack of accurate and harmonised information across SmPC is however observed. In general terms, it is recommended to use the “lowest possible dose” for symptom relief and make gradual adaptation of the dose to the pain. Regarding the maximum acetaminophen dose, some SmPC mention that “it is generally not necessary to exceed 3 g per 24 hours”. Regarding dose adjustments for special populations (liver failure, renal failure, dehydration, weight < 50 kg…), although it is formulated differently across SmPC, it is recommended to use the lowest possible effective doses, and specifically to increase interval between two intakes (> 8 h) in severe chronic renal failure. The maximum recommended doses in special population are given as an indication (sometimes 2 g/day or 3 g/day) but are not necessarily related to clinical studies (no reference provided in SmPC).

Few studies have described acetaminophen prescription patterns in hospitals or assessed compliance with recommendations relating to HRFs: in French and American cohorts, failure to adjust doses in view of the presence of HRFs was observed in 1 to 21% of prescriptions [27,28,29,30,31]. It can be noted that neither the type of hospital units (surgery, geriatrics...) nor pharmaceutical validation studies have an influence on dose adjustment [27, 30].

This work was performed after the notification in our local Pharmacovigilance unit of cases of acetaminophen toxicity at doses in the therapeutic range among patients with HRFs: the most recent, with a fatal outcome, concerned a 72-year-old hospitalised man who developed cytolysis with acute hepatic failure 2 days after the initiation of 4 g/day acetaminophen for acute pain. The patient’s history included alcoholism and cachexia, in a context of hepatic steatosis, septic shock and the discovery of metastatic colorectal cancer.

As we believe that some HRFs are more likely to induce dose adjustments than others, the aim of our study was to assess to what extent the existence of HRFs (single or in combination) modify the prescribers’ choice of acetaminophen dose (< 4 g/day versus 4 g/day).

Materials and methods

We conducted a retrospective monocentric cross-sectional study including all patients with an acetaminophen prescription in Rennes University Hospital.

All data was collected in accordance with the French legislation on retrospective clinical studies, in accordance with the precepts established by the Helsinki declaration.

Data sources

The extraction of data concerning acetaminophen prescriptions (oral and intravenous) (Dxcare® software version 7.5.20p049, Medasys®) was carried out over 1 week, from 13 to 19 December 2017. Only patients aged over 18 years, i.e. born after December 12, 1999, were considered for this analysis.

Exposure

All medications containing acetaminophen were considered, prescribed on their own or in combination with other drugs. We collected the names of the medications, the routes of administration and the daily doses. Patients were categorised as having a maximum dose of 4 g/day or less than 4 g/day. The patients for whom the dose was specified as “1 g ‘upon request’, maximum 4 times a day,” were considered as having the maximum 4 g/day dose.

Other variables

Data was collected from the patients’ electronic files: age at the time of the acetaminophen prescription, gender, hospital unit, weight, body mass index, biological parameter values (serum creatinine, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (PAL), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), direct bilirubin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time (TP), international normalised ratio (INR), factor V, serum albumin and pre-albumin), the presence of chronic viral hepatitis (B or C) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), current chronic alcoholism, current intake of oral anticoagulants, current malnutrition, history of liver or renal transplantation.

Risk factors predisposing to hepatotoxicity

According to the SmPC and French recommendations on acetaminophen prescription [24,25,26], we considered seven HRF categories that should lead to dose adjustment, defined as follows:

-

Age over 75 years, i.e. patients born before the 12 December 1942;

-

Low weight: under 50 kg;

-

Malnutrition defined by the presence of one or more of the following criteria: serum albumin < 30 g/L, serum pre-albumin < 150 mg/L, BMI < 18.5 for patients < 70 years old, BMI < 21 for patients ≥ 70 years old, the specific mention of “malnutrition” in the electronic file;

-

Chronic alcoholism: we selected patients whose electronic file records specified excessive and chronic alcohol consumption;

-

Current chronic viral infections (hepatitis B, C and/or D) and/or HIV; patient status was individually checked by a virologist (CP author). HIV patients with an undetectable viral load were considered as presenting a risk factor; patients who had recovered from hepatitis C at study entry were not considered as presenting a risk factor;

-

Severe chronic renal failure defined by a creatinine clearance value (estimated by the CKD-EPI equation) of < 30 mL/min in the electronic file;

-

Hepatocellular insufficiency, biologically defined by one or more following abnormalities: factor V < 70%, prothrombin time decrease, INR > 1.5 for patients without anticoagulant treatment or INR > 5 with anticoagulant treatment, ALT > 40 UI/L, AST > 40 UI/L. Other biological parameters were considered only in case of association with other abnormalities: serum albumin concentration < 35 g/L and/or the following clinical signs specified in the electronic file: “jaundice”, “hepatic encephalopathy”, “cirrhosis”, “stellate angioma” or “palmar erythrosis”, “alcoholic hepatitis”, “viral hepatitis”.

Statistical methods

In case of several acetaminophen prescriptions for the same patient, only the first was considered for the descriptive and statistical analyses in order to ensure the independence of the data and analyses. We considered the first prescription as the initial prescriber’s intention to treat, as the second or following prescriptions could be related to medical or pharmaceutical re-assessment.

Descriptive statistics characterised patients at the time of the first acetaminophen prescription. Proportions were compared across levels of exposure using chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test; age was compared using the Student t test.

A logistic regression model considering all HRFs was used to estimate those that were significantly related to the prescribers’ choice of acetaminophen dose (< 4 g/day versus 4 g/day).

A descending step-by-step selection model was used, retaining only the variables (HRF) significantly associated with acetaminophen dose adjustment (< 4 g/day) at a 5% statistical threshold.

An odds ratio estimation was used to determine which HRFs were associated with dose adjustment (< 4 g/day or 4 g/day) in the prescribers’ prescriptions.

All analyses were conducted using the SAS statistical package (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Over a 7-day period in December 2017, 2338 acetaminophen prescriptions were collected from Rennes University Hospital. After excluding prescriptions for patients under 18 years, 2048 acetaminophen prescriptions concerning 1842 patients were included in this study. Retaining only the first prescription for each patient, 1842 prescriptions were used for the analyses (see Fig. 1)

.

The characteristics of the study population are displayed in Table 1. Around 54% were female. The median age was 65 years (min 18 years to max 101 years) and 32.9% were over 75 years old.

Among the 1842 prescriptions, 73.7% were for 4 g/day (Table 1); it can be noted that no prescription exceeded the maximum 4-g daily dose. Females were more frequently in the < 4 g/day group than in the 4 g/day group (60.1% versus 51.3%, p < 0.001). Regarding the hospital unit, in the < 4 g/day group, prescribers mainly belonged to geriatric or other clinical units (respectively 44.6% and 41.1%); in the 4 g/day group, prescriptions mainly derived from surgery/anaesthesia/intensive care/palliative units and other clinical units (respectively 57.1% and 32.6%).

Around 55% of the overall population presented with at least one HRF. Among patients with only one HRF (n = 549), the HRF was mainly age > 75 years, and secondarily hepatocellular insufficiency or chronic alcoholism (Appendix Table 1). Whereas around 80% of prescriptions in the < 4 g/day group were for patients with at least 1 HFR, only 53% of prescriptions in the 4 g/day group concerned patients without any HFR (p < 0.001). Furthermore, some HRFs were significantly more frequent in the < 4 g/day group (Table 1): age > 75, low weight, malnutrition and severe renal failure.

Concerning the statistical analysis, only prescriptions without missing data on the HRF category were used (n = 1103), including 363 patients in the < 4 g/day group and 740 in the 4 g/day group. The logistic regression showed that age > 75 and low weight were significantly associated with the prescriber’s choice of dose (Table 2). The descending step-by-step model confirmed that only age > 75 and low weight remained significantly associated with the < 4 g/day dose (data not shown). We observed similar results in a sensitivity analysis using age > 75 and weight as continuous variables (data not shown).

It can be noted that among patients > 75 years (n = 606), who accounted for one third of the overall population, all had 1 (n = 315) or 2 (n = 291) HRFs. Despite this, around 50% (n = 302) had no dose adjustment.

As regards the administration route, 63 (3.4%) concerned intravenous use, most of whom (86%; n = 54) had a 4 g/day dose. In those patients, at least one HRF was recorded in 34 patients. As regards the 9 patients in the < 4 g/day group, 1 had no HRF, 2 had only one HRF (age > 75 in both cases) and 7 had at least 2 HRFs. More in depth, Paracetamol B Braun 1 g/100 mL® (adult formulation) was used in all cases. Its SmPC recommends a dose adjustment considering weight category (between 33 and 50 kg or > 50 kg) and whether HRFs are present (chronic alcoholism, hepatocellular insufficiency, chronic malnutrition and dehydration for which maximal dose is 3 g/day).

Discussion

In our 7-day study focusing on acetaminophen prescriptions in Rennes University Hospital, around three quarters of prescriptions were full-dose (4 g/day); in this group, 47% of prescriptions were for patients with at least one HRF: these can be considered as non-compliant prescriptions, and the proportion is greater than in previous studies showing up to 21% of non-compliant acetaminophen prescriptions in hospital [27,28,29,30,31]. The lower non-compliant prescriptions could be related to the fact that age > 75 years is not considered as a HRF in SmPC and no dose adjustment is recommended. As mentioned by Pacé et al., medicine and geriatric units seem to be more aware of the HRFs of acetaminophen [31]: in our study, the number of prescriptions for < 4 g/day in these units amounted to around 85% of the prescriptions.

For the HRFs studied, we showed that age > 75 years and low weight influenced the prescribers’ choice of dose. The impact of advanced age here could be linked to age in our cohort since the median age was 65.0 years and one third of the patients were over 75 years old. Another explanation linked to age is the fact that, in Rennes University Hospital, prescribers are particularly aware of dosage adjustment for elderly patients thanks to careful monitoring by the pharmacists. Surprisingly, neither chronic alcoholism nor hepatocellular insufficiency was associated with dose adjustment. Although acetaminophen is a highly hepatotoxic drug and its metabolism involves the liver, prescribers appear not to consider these HRFs in their choice of dose. Hepatic tests after acetaminophen initiation were not performed in our study, so we could not check for clinical or biological signs of hepatotoxicity among patients with these HRFs. Pace et al. also observed a high rate of non-compliance with recommendations (> 68%) for patients with chronic alcoholism or hepatocellular insufficiency [31], suggesting that prescribers need to be made aware of dose adjustments in these patient groups. Unlike our study where low weight was a dose-adjustment variable in acetaminophen prescriptions by clinicians, this factor was explored in heterogeneous manner in other studies and was related to non-compliance [29, 31].

None of the prescriptions exceeded the 4 g per day, which is no doubt linked to the use of software (DxCare®) limiting acetaminophen daily doses; a warning is also displayed when several drugs containing acetaminophen are coprescribed.

Some HRFs as well as their definition can be discussed. In a literature review, Caparrotta et al. found no good quality evidence to establish that factors were HRFs [11]. They notably pointed that the safe oral acetaminophen dose in patients < 50 kg had not been established. In our study, chronic alcoholism status has only been identified through a subjective HRF reading (potentially underestimated) without re-assessment by an independent committee. No additional information was collected (severity, care…). Age, especially advanced age is described as HRF whereas literature data are inconsistent (PK, case series, population-based studies) [11, 12]. As evoked by Caparrotta et al. there is a lack of good quality clinical evidence that older people have a clinically significant difference in acetaminophen metabolism or are at increased risk of toxicity at (supra)therapeutic dose. Age cut-off also varied across studies [12, 32,33,34]. Moreover, neither French SmPC nor recommendations provide an age cut-off. Considering that “old age” definition is complex, potentially subjective (physical, psychological conditions), and is not only related to years, we arbitrarily chose 75 years old as cut-off in our study. In addition to biological criteria, hepatocellular insufficiency definition also included a HRF reading seeking specific terms (cirrhosis, hepatic encephalopathy) without secondary objective re-assessment. All these limitations could have induced misclassification bias of HRF.

The main strength of our work lies in the data collection that took place within a week and involved all adult patients’ electronic files in all Rennes University Hospital units. Among the weaknesses, we recognise that our results concern only one hospital and may not be representative of French hospital prescribers. The objective of our study was not to compare with practices in other hospitals but rather to highlight the fact that HRFs are not always considered by prescribers, even in university hospitals, when prescribing acetaminophen. Also, we did not consider the indication for acetaminophen, treatment duration or the potential need for opioid treatments, which could have impacted dose adjustment. Considering a safety approach, we deliberately focused our study on the first acetaminophen dose prescribed, irrespective of its indication, as representing intention-to-treat. Furthermore, our statistical analysis did not include all the 1842 prescriptions in the overall population as a result of missing data for some HRFs: around 33% of patients had missing data for the hepatocellular insufficiency variable, and 10% for malnutrition status. It can be noted that some HRFs could have been underestimated, especially alcoholism which is often concealed by patients when questioned on the subject. We did not assess either whether the 4 g/day dose for patients with one or more HRFs had clinical significance for liver function, nor did we consider the type of HRF; indeed, hepatic cytolysis is more likely among patients with cirrhosis than among elderly patients without other liver diseases. We did not consider co-medication and especially drug-drug interaction, nor other clinical conditions (sepsis, heart failure [35, 36]) that affect the hepatic enzymes. In acetaminophen SmPC, drug interaction section mentioned a precaution of use when associated with other hepatotoxic drugs or CYP 450 drug enzyme inducers. However, on the basis of the French drug-drug interaction referential provided by the French Health Authorities (French National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM)) [37], no clinically significant interaction with paracetamol was highlighted, even with drugs impacting CYP 2E1 (doxycycline, isoniazide).

We should bear in mind that, although acetaminophen is the most widely recognised drug in inducing liver damage [38, 39], its use is commonplace, mainly as a result of a good reputation with regard to safety compared with other analgesic drugs (non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs for example). In order to limit the risk of poisoning and suicide using acetaminophen, France was the first country in Europe in the 1980s to limit packaging to a maximum dose of 8 g of acetaminophen. In the 2000s, the Federal Drug Agency in the USA and the UK health authorities also restricted the acetaminophen pack size [40, 41]; the FDA also limited the acetaminophen dosage unit to 325 mg in 2011 [42, 43]. Despite this, acetaminophen remains the first drug involved in overdose (intentional or otherwise) [1, 2]. In 2017, Lee described the controversy surrounding acetaminophen use in pain management [9]: he pointed out that worldwide regulatory efforts had been ineffective in reducing the cost in money and lives resulting from its hepatotoxicity. In France, however, the French Pharmacovigilance network regularly collects case reports of acute acetaminophen poisoning. A recent fatal case in December 2017, which was highly publicised across France, led the health authorities to reinforce the data available on acetaminophen-based drugs: the objective was to raise awareness among patients and prescribers about liver damage. A public consultation was thus initiated on August 20, 2018, ending on September 30, 2018, for the definition of the best warning message to put on drug packaging [44], but the results have not yet been issued. With the exception of hepatocellular insufficiency, there is a lack of information on dose adjustment, special warnings or contraindications in case of other HRFs with some acetaminophen-based medications (e.g. Paracetamol Teva 1 g, tablets; Paracetamol EG 500 mg/30 mg®, effervescent scored tablets; Paracetamol Zydus 500 mg, gelules ®… [45,46,47]). It is worth noting that maximum dose could vary from one SmPC to another: for instance, in case of HRF, 2 g/day is mentioned in Paracetamol AHCL 1 g, effervescent tablet [48] compared with 3 g/day in Doliprane 1 g, tablets [49]. In general terms, lack of SmPC harmonisation, especially regarding the appropriate maximal dose to be used in case of HRF, is a limitation for clinicians’ prescriptions compliance. ANSM planned a harmonisation of the warnings included in the SmPC for acetaminophen-based drugs in 2019.

Considering pharmacovigilance case report of acetaminophen toxicity in patients with HRF treated with (sub)therapeutic ⩽ 4 g/day dose and the results of the current study, in Rennes University Hospital, several improvement measures are planned: awareness raising at the residents’ welcome seminars twice a year, poster campaign in clinical departments, configuration of software as regards prescription schemes, awareness raising of pharmacist responsible for prescriptions’ pharmaceutical validation.

Conclusion

This work shows that, in Rennes University Hospital, HRFs are not systematically considered by clinicians when acetaminophen is prescribed. Age > 75 years and low weight had a greater impact on acetaminophen prescription than alcoholism, malnutrition, chronic viral hepatitis, severe renal failure or hepatocellular insufficiency. Considering the widespread use of acetaminophen, it appears important to remind healthcare professionals and patients of the hepatotoxicity risk resulting from misuse, especially in the presence of HRF.

References

Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, Fraser MO, Banner W (2017) 2016 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 34th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 55:1072–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1388087

Guerlais M et al (2018) Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, and INSERM Clinical Research Centers (CIC) Meeting, 12-14 June 2018, Toulouse, France “Misuse of analgesics in the context of self-medication: resutls of a large cross-sectional survey from the DANTE study (une Décennie d’ANTalgiques en France) (CO-041). Fundam Clin Pharmacol 32:16. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcp.12370

Bernal W, Auzinger G, Dhawan A, Wendon J (2010) Acute liver failure. Lancet 376:190–201

Hawton K, Bergen H, Simkin S, Dodd S, Pocock P, Bernal W, Gunnell D, Kapur N (2013) Long term effect of reduced pack sizes of paracetamol on poisoning deaths and liver transplant activity in England and Wales: interrupted time series analyses. BMJ 346:f403

Gulmez SE, Larrey D, Pageaux G-P, Bernuau J, Bissoli F, Horsmans Y, Thorburn D, McCormick PA, Stricker B, Toussi M, Lignot-Maleyran S, Micon S, Hamoud F, Lassalle R, Jové J, Blin P, Moore N (2015) Liver transplant associated with paracetamol overdose: results from the seven-country SALT study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80:599–606

Vale JA, Proudfoot AT (1995) Paracetamol (acetaminophen) poisoning. Lancet 346:547–552

Bateman DN (2015) Paracetamol poisoning: beyond the nomogram. Br J Clin Pharmacol 80:45–50

Rumack BH, Bateman DN (2012) Acetaminophen and acetylcysteine dose and duration: past, present and future. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 50:91–98

Lee WM (2017) Acetaminophen (APAP) hepatotoxicity-Isn’t it time for APAP to go away? J Hepatol 67:1324–1331

Twycross R, Pace V, Mihalyo M, Wilcock A (2013) Acetaminophen (paracetamol). J Pain Symptom Manag 46:747–755

Caparrotta TM, Antoine DJ, Dear JW (2018) Are some people at increased risk of paracetamol-induced liver injury? A critical review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 74:147–160

(2018) What dose of paracetamol for older people? Drug Ther Bull 56:69–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/dtb.2018.6.0636

Schena FP (2011) Management of patients with chronic kidney disease. Intern Emerg Med 6(Suppl 1):77–83

Blantz RC (1996) Acetaminophen: acute and chronic effects on renal function. Am J Kidney Dis 28:S3–S6

Larrey D (2006) Is there a risk to prescribe paracetamol at therapeutic doses in patients with acute or chronic liver disease? Gastroenterol Clin Biol 30:753–755

Bunchorntavakul C, Reddy KR (2013) Acetaminophen-related hepatotoxicity. Clin Liver Dis 17:587–607 viii

Kurtovic J, Riordan SM (2003) Paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity at recommended dosage. J Intern Med 253:240–243

Eriksson LS, Broomé U, Kalin M, Lindholm M (1992) Hepatotoxicity due to repeated intake of low doses of paracetamol. J Intern Med 231:567–570

Krähenbuhl S, Brauchli Y, Kummer O et al (2007) Acute liver failure in two patients with regular alcohol consumption ingesting paracetamol at therapeutic dosage. Digestion 75:232–237

Forget P, Wittebole X, Laterre P-F (2009) Therapeutic dose of acetaminophen may induce fulminant hepatitis in the presence of risk factors: a report of two cases. Br J Anaesth 103:899–900

Claridge LC, Eksteen B, Smith A, Shah T, Holt AP (2010) Acute liver failure after administration of paracetamol at the maximum recommended daily dose in adults. BMJ 341:c6764

Watkins PB, Kaplowitz N, Slattery JT, Colonese CR, Colucci SV, Stewart PW, Harris SC (2006) Aminotransferase elevations in healthy adults receiving 4 grams of acetaminophen daily: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 296:87–93

Heard K, Green JL, Anderson V, Bucher-Bartelson B, Dart RC (2014) A randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine the course of aminotransferase elevation during prolonged acetaminophen administration. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 15:39

Agence Nationale d’Accréditation et d’Évaluation en Santé (ANAES) (2000) Evaluation et prise en charge thérapeutique de la douleur chez les personnes âgées ayant des troubles de la communication verbale - https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/Douleur_sujet_age_Recos.pdf

Haute Autorité de Santé (2007) Surveillance des malades atteints de cirrhose non compliquée et prévention primaire des complications - Recommandations - https://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/application/pdf/surveillance_cirrhose_-_recommandations_2008_02_13__17_41_31_104.pdf

Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé (AFSSAPS) (2011) Prise en charge des douleurs de l’adulte modérées à intenses. In: Recommandations après le retrait des associations dextropropoxyphène/paracétamol et dextropropoxyphène/paracétamol/caféine

Arques-Armoiry E, Cabelguenne D, Stamm C, Janoly-Dumenil A, Grosset-Grange I, Vantard N, Maire P, Charpiat B (2010) Most frequent drug-related events detected by pharmacists during prescription analysis in a university hospital. Rev Med Interne 31:804–811

Zhou L, Maviglia SM, Mahoney LM, Chang F, Orav EJ, Plasek J, Boulware LJ, Lou H, Bates DW, Rocha RA (2012) Supratherapeutic dosing of acetaminophen among hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 172:1721–1728

Charpiat B, Henry A, Leboucher G, Tod M, Allenet B (2012) Overdosed prescription of paracetamol (acetaminophen) in a teaching hospital. Ann Pharm Fr 70:213–218

Viguier F, Roessle C, Zerhouni L, Rouleau A, Benmelouka C, Chevallier A, Chast F, Conort O (2016) Clinical pharmacist influence at hospital to prevent overdosed prescription of acetaminophen. Ann Pharm Fr 74:482–488

Pace J-B, Nave V, Moulis M, Bourdelin M, Coursier S, Jean-Bart É, Leroy B, Bonnefous JL, Bontemps H, Coutet J, Eyssette C, Pont E (2017) Prescription of acetaminophen in five French hospitals: what are the practices? Therapie 72:579–586

Wynne HA, Cope LH, Herd B et al (1990) The association of age and frailty with paracetamol conjugation in man. Age Ageing 19:419–424

Mitchell SJ, Hilmer SN, Murnion BP, Matthews S (2011) Hepatotoxicity of therapeutic short-course paracetamol in hospital inpatients: impact of ageing and frailty. J Clin Pharm Ther 36:327–335

Liukas A, Kuusniemi K, Aantaa R, Virolainen P, Niemi M, Neuvonen PJ, Olkkola KT (2011) Pharmacokinetics of intravenous paracetamol in elderly patients. Clin Pharmacokinet 50:121–129

Yan J, Li S, Li S (2014) The role of the liver in sepsis. Int Rev Immunol 33:498–510

Koehne de Gonzalez AK, Lefkowitch JH (2017) Heart disease and the liver: Pathologic Evaluation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 46:421–435

Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé (ANSM) (2018) Thésaurus des interactions médicamenteuses - mise à jour mars 2018

Leise MD, Poterucha JJ, Talwalkar JA (2014) Drug-induced liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc 89:95–106

Fisher K, Vuppalanchi R, Saxena R (2015) Drug-induced liver injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med 139:876–887

Hawkins LC, Edwards JN, Dargan PI (2007) Impact of restricting paracetamol pack sizes on paracetamol poisoning in the United Kingdom: a review of the literature. Drug Saf 30:465–479

Krenzelok EP (2009) The FDA Acetaminophen Advisory Committee meeting - what is the future of acetaminophen in the United States? The perspective of a committee member. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 47:784–789

Federal Drug Agency (FDA) Prescription drug products containing acetaminophen: actions to reduce liver injury from unintentional overdose. Notice Document. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=FDA-2011-N-0021-0001. Accessed 10 Sep 2018

Federal Drug Agency (FDA) FDA Drug Safety Communication:[1-13-2011] prescription acetaminophen products to be limited to 325 mg per dosage unit; boxed warning will highlight potential for severe liver failure https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm239821.htm. Accessed 10 Sep 2018

Paracétamol : l’ANSM lance une consultation publique pour sensibiliser les patients et les professionnels de santé au risque de toxicité pour le foie en cas de mésusage - Point d’Information - ANSM : Agence nationale de sécurité du médicament et des produits de santé. https://ansm.sante.fr/S-informer/Points-d-information-Points-d-information/Paracetamol-l-ANSM-lance-une-consultation-publique-pour-sensibiliser-les-patients-et-les-professionnels-de-sante-au-risque-de-toxicite-pour-le-foie-en-cas-de-mesusage-Point-d-Information. Accessed 10 Sep 2018

Résumé des caractéristiques du produit - Paracétamol Teva 1g, comprimé. http://agence-prd.ansm.sante.fr/php/ecodex/rcp/R0291484.htm. Accessed 10 Sept 2018

Résumé des caractéristiques du produit - Paracétamol Codéine EG 500 mg/ 30 mg, comprimé effervescent sécable. http://agence-prd.ansm.sante.fr/php/ecodex/rcp/R0286140.htm. Accessed 10 Sept 2018

Résumé des caractéristiques du produit - Paracétamol Zydus 500 mg, gélule. http://agence-prd.ansm.sante.fr/php/ecodex/frames.php?specid=67445776&typedoc=R&ref=R0230023.htm. Accessed 10 Sept 2018

Résumé des caractéristiques du produit - Paracétamol AHCL 1g, comprimé effervescent. (page consultée le 17/01/2019). http://agence-prd.ansm.sante.fr/php/ecodex/frames.php?specid=61754805&typedoc=R&ref=R0328124.htm. Accessed 17 Jan 2019

Résumé des caractéristiques du produit - Doliprane 100 mg, comprimé. (page consultée le 17/01/2019). http://agence-prd.ansm.sante.fr/php/ecodex/frames.php?specid=60234100&typedoc=R&ref=R0301400.htm. Accessed 17 Jan 2019

Acknowledgements

Administrative, technical or material support was provided by Rennes Hospital University. We thank Jean-Paul Sinteff (Medical Information Departement, CHU Rennes) for the DxCare® software data extraction, and Adrien Turban, Anne-Sophie Michel, Justine Geffroy and Stephanie Ollivier for their help in the data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LMS and AB had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. SP, EP, LMS and AB were part of the study concept and design. All authors were a part in the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data. Drafting of the manuscript was done by LMS. All authors took part in the critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. LMS was a part in the statistical analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All data was collected in accordance with the French legislation on retrospective clinical studies, in accordance with the precepts established by the Helsinki declaration.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

What is already known about this subject:

• Acetaminophen is widely known to be a hepatotoxic drug.

• Recommendations include a maximum daily dose of acetaminophen of < 4 g/day for patients with hepatotoxicity risk factors (chronic alcoholism, hepatocellular insufficiency, advanced age, anorexia…).

• Studies have described up to 21% of acetaminophen prescriptions without dose adjustment among patients with hepatotoxicity risk factors.

What this study adds:

• Age > 75 and weight < 50 kg are linked to prescriptions of < 4 g/day.

• Chronic alcoholism, hepatocellular insufficiency, severe chronic renal failure, chronic viral infections and malnutrition have no influence on the choice of the dose.

• Clinicians should systematically assess patient history, checking for any hepatotoxicity risk factors when prescribing acetaminophen.

Appendix Table 1.

Appendix Table 1.

Repartition of patients with only one hepatotoxicity risk factor (n= 549) by type of risk factor.

For this descriptive step, we made the hypothesis if a HRF was present it would be clearly specified in the electronic file otherwise it was absent; the missing value were then changed to 0.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bacle, A., Pronier, C., Gilardi, H. et al. Hepatotoxicity risk factors and acetaminophen dose adjustment, do prescribers give this issue adequate consideration? A French university hospital study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 75, 1143–1151 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02674-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-019-02674-5