Abstract

Purpose

Adverse drug events (ADE) are among the leading causes of morbidity and hospitalization. This review analyzes risk factors for ADE, particularly their categorizations and association patterns, the prevalence, severity, and preventability of ADE, and method characteristics of reviewed studies.

Methods

Literature search was conducted via PubMed, Science Direct, CINAHL, and MEDLINE. A review was conducted of research articles that reported original data about specific risk factors for ADE since 2000. Data analyses were performed using Excel and R.

Results

We summarized 211 risk factors for ADE, and grouped them into five main categories: patient-, disease-, medication-, health service-, and genetics-related. Among them, medication- and disease-related risk factors were most frequently studied. We further classified risk factors within each main category into subtypes. Among them, polypharmacy, age, gender, central nervous system agents, comorbidity, service utilization, inappropriate use/change use of drugs, cardiovascular agents, and anti-infectives were most studied subtypes. An association analysis of risk factors uncovered many interesting patterns. The median prevalence, preventability, and severity rate of reported ADE was 19.5% (0.29%~86.2%), 36.2% (2.63%~91%), and 16% (0.01%~47.4%), respectively.

Conclusions

This review introduced new categories and subtypes of risk factors for ADE. The broad and in-depth coverage of risk factors and their association patterns elucidate the complexity of risk factor analysis. Managing risk factors for ADE is crucial for improving patient safety, particularly for the elderly, comorbid, and polypharmacy patients. Some under-explored risk factors such as genetics, mental health and wellness, education, lifestyle, and physical environment invite future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adverse drug events (ADE) can cause mild to severe harm and even death to patients [1,2,3,4]. Preventable ADE are among the leading cause of death in the USA [5]. Risk factors are defined as conditions or measurements associated with the probability of disease or death not necessarily recognized by the patient [6,7,8]. For instance, the most commonly prescribed drugs for type 2 diabetes are potentially associated with an increased risk of acute pancreatitis occurrence [9]. ADE mainly consist of adverse drug effects and adverse drug reactions, among others [10]. The latter two are related but differ in that adverse drug effects are usually detected by laboratory tests or by clinical investigations, and adverse drug reactions are detected by their clinical manifestations (symptoms and/or signs) [10]. Adverse drug effects may account for up to 140,000 deaths annually in USA [11, 12], which cost more than 3000 dollars per patient on average in community hospitals and increase the length of stay by 3.1 days an average [13]. Adverse drug reactions occur frequently in the post-discharge period [14], which cost about 136 billion USD, and cause 1 out of 5 injuries or death per year to hospitalized patients, according to the FDA. The cost of drug-related morbidity and mortality exceeded 177.4 billion dollars in 2000 [15]. There were 47,055 drug overdose deaths in the USA in 2014 [16]. Many adverse drug reactions could potentially have been prevented or ameliorated with simple strategies [14]. Therefore, this review study investigates risk factors for ADE, including adverse drug effects and adverse drug reactions.

There are a handful of review articles on risk factors for ADE; however, their coverage of risk factors is very limited. For instance, Alomar [17] provided a categorization scheme of risk factors for adverse drug reactions, which did not consider those for adverse drug effects. In addition, the scheme consists of four main categories: patient-related, drug-related, disease-related, and social factors [17, 18], but ignores health service-related risk factors. Boeker et al. [19] focused on adverse drug effects in surgical and non-surgical inpatients but excluded children and incidents registered in the emergency department and outpatient clinical settings. Al Hamid et al. [20] studied 9 risk factors for ADE (e.g., old age, depression, and immobilization) in adult patients. Resende and Santos-Neto [21] summarized 9 risk factors for adverse drug reactions to antituberculosis drugs (e.g., age, gender, treatment regimen, HIV co-infection, and genetic factors). Due to their limited scopes, previous reviews covered a much smaller number of original research studies than the current investigation. More importantly, these review studies did not attempt to categorize risk factors; even when they provide such a categorization, it is very general, and does not offer a systematic understanding of risk factors. Furthermore, none of the previous studies has examined the association patterns among different risk factors for ADE (when two or more risk factors co-exist), and the latter can be instrumental for illuminating the complex interactions among risk factors.

To address the above limitations, this review aims to provide a broad and in-depth understanding of risk factors for ADE, by covering more and recent related studies, categorizing risk factors, analyzing their association patterns, summarizing the prevalence, severity, and preventability of ADE, and identifying method characteristics of related original research studies.

Methods

This review includes studies that contain original research results pertaining to specific risk factors for ADE. It excludes articles that do not provide details about specific risk factors, and that are not related to ADE, written in languages other than English, or published before 2000.

We conducted literature search in multiple databases, including PubMed, Science Direct, CINAHL, and MEDLINE, during July to September 2016. The search queries were a combination of risk factor and any of the variant expressions of ADE such as drug related side effects, adverse drug effects, medicine-related problems, drug therapy problems, ADE, adverse drug event, adverse drug reaction, and ADR.

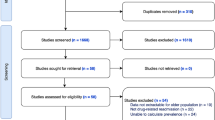

Figure 1 illustrates detailed steps of our article selection process. The search queries were used to match against the titles and abstracts of publications. The matched search results were further expanded by including matched articles from their lists of references using the snowballing method. The expanded set of 661 articles went through an initial screening process based on our review of their abstracts and subsequently browsing of full texts. Among them, 247 titles deemed pertinent to our study were selected for detailed full-text review. The review led to the removal of studies that did not report data about specific risk factors for ADE. Finally, the remaining 106 articles were selected for our investigation of risk factors for ADE.

In addition to risk factors, we also extracted the prevalence, preventability, and severity rates of ADE as authors reported in their studies, if any. These rates are defined as the percentage of patients who experienced ADE, preventable ADE, and severe ADE, respectively, which indicate the significance of studying their risk factors. In view that the method design of previous studies can inform future research, we identified six key aspects of research methods used by the selected studies, including data collection location (e.g., country), setting (e.g., hospital), participants (e.g., population type), duration of the study, sample size, and research type (e.g., case-control study).

The authors selected articles based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria and prepared instructions for data extraction from those articles. Two reviewers carried out the extraction task independently. One reviewer completed all the selected articles, and the other processed a randomly selected subset of 40 articles. An analysis of inter-rater reliability of extracted risk factors from the overlapped articles yielded a kappa statistic of 0.74. The two reviewers discussed inconsistent results via two face-to-face meetings, and a third reviewer adjudicated the results. Based on the feedbacks from the discussion and adjudication, the first reviewer reviewed her extraction results for the remaining 66 articles and revised them as appropriate.

Starting with the collection of verified risk factors, the first and the third reviewers categorized the risk factors independently in two steps. The first step involved grouping risk factors into main categories, and the second step involved further grouping risk factors within each main category into subtypes. The grouping results were discussed via face-to-face meetings to resolve any differences. The second step started after the reviewers had reached a consensus on the main categories. The subcategorization of some main types was conducted via mapping by drawing on corresponding medical resources, including ICD, a drug taxonomy, and an integrated database of human genes [22]. For several risk factors that involved mapping ambiguities, we consulted a fourth reviewer who held a medical degree for further validation. The subtypes of remaining main categories were determined based on consensus.

The association patterns among different risk factors were extracted using association analysis. Association analysis is a technique for discovering strong and interesting relationships between items (e.g., risk factors) that are hidden in a dataset (e.g., research studies) [23]. The uncovered relationships or patterns can be represented in form of association rule, RFL → RFR, where both RFL and RFR belong to a set of risk factors for ADE. The strength of an association rule can be measured by support and confidence, and its interestingness by lift [24]. Support is computed as the ratio of research studies that investigated a particular set of risk factors (RFL and RFR), and confidence as the ratio of research studies that investigated RFL simultaneously investigated RFR. Lift is defined as a ratio of the confidence of an association rule to the support of RFR. A rule is generally considered interesting if lift > 1, which indicates that RFL are useful for predicting RFR. In addition, we selected subtype of risk factors as the unit of association analysis to seek a middle ground for the level of detail of association rules.

Results

Based on our analysis of the selected articles, we summarized to a total of 211 specific risk factors, introduced a two-level classification scheme of the risk factors, and discovered association patterns of risk factors.

Categorization of risk factors

We grouped those factors into five main categories—patient-related (e.g., age, gender), disease-related (e.g., history and comorbidity), medication-related (e.g., polypharmacy), health service-related (e.g., #prescribing physicians), and genetics risk factors (e.g., MHC class I), as shown in Table 1. Among them, medication- and disease-related risk factors dominate the previous studies. We further divided each of the main categories of risk factors into its subtypes.

For the patient-related risk factors, we grouped them into nine subtypes, including age, gender, weight, ethnic group, ADE history, socioeconomic status, lifestyle, functional status, and treatment compliance. Age and gender are most frequently studied subtypes, among others. It is shown from Table 1 that most studies focus on the elderly and a few on the young population. Among the studies of gender, some focused on females [29, 31, 35, 39, 40, 42, 43, 47, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61], some others on males [34, 36, 62], and yet a few others on gender in general [26, 33, 54]. Lifecycle is another highly reported risk factors subcategory such as alcohol abuse [29, 43, 70, 71], history of alcohol consumption [43], higher alcohol consumption [72], and smoking status [33, 73].

The categorization of the disease-related risk factors followed ICD, which consisted of the following subtypes: comorbidity, genitourinary system disorders, nervous system diseases, circulatory system diseases, musculoskeletal system and connective tissue diseases, digestive system disorders, mental and behavioral disorders, lower respiratory diseases, oncology disorders, certain infectious and parasitic diseases, immunodeficiency and blood diseases, disease complexity and medical history, and health condition. Among them, comorbidity is most frequently reported. In other words, patients with a high number of medical conditions are subject to higher risks of ADE. In addition, genitourinary system disorders, circulatory system diseases, and immunodeficiency and blood diseases contained a relatively higher number of risk factors than the rest of the disease-related subcategories. We can infer that patient with the above disease conditions are highly susceptible to ADE.

For the medication-related risk factors, we grouped them based on drug classes into subtypes as the following: polypharmacy, cardiovascular agents, central nervous system agents, anti-infectives, antineoplastic agents, psychotherapeutic agents, metabolic agents, gastrointestinal drugs, inappropriate use or change of drugs, intravenous use of drugs, and miscellaneous agents. Among them, polypharmacy receives the highest rate of reporting. In addition, the results show that central nervous system agents and cardiovascular agents are more likely to lead to ADE compared with drugs used to treat other medical conditions. Interestingly, inappropriate use or change of drugs is another common category of medication-related risk factors, which is potentially preventable.

We grouped health service-related risk factors into two subtypes: service utilization and service provision. The results also reveal that postoperative days after hospital discharge [54] and cost associated with getting access to medical services ⁄medicines [78] are significant risk factors for ADE.

The genetic risk factors were grouped based on their gene families with reference to an integrated database of human genes [22]. These gene families include MHC class I, ABC transporter, cytochrome P450, VKOR, concentrative nucleoside transporter, glycosyltransferase 29 family, ETS transcription factor, peptidase M13, and serine hydrolase enzyme. Among them, the first three gene families were most frequently studied.

There was a total of 45 subtypes of risk factors. Figure 2 shows the distribution of article account over various subtypes of risk factors that were reported in three or more research studies. The figure shows that the top-10 most frequently reported subtypes of risk factors for ADE are polypharmacy, age, gender, comorbidity, inappropriate use or change use of drugs, central nervous system agents, cardiovascular agents, service utilization, anti-infectives, and lifestyle.

Association patterns of risk factors

Prior to the association analysis, we need to first answer the question of whether more than one subtype of risk factors has been investigated by a significant percentage of previous studies. To this end, we summarized article count for varying number of subtypes of risk factors for ADE. The results show that 73 articles (~69%) reported two or more subtypes of risk factors. Among them, 26 studies examined two and 20 studies examined three subtypes of risk factors, respectively; eight studies investigated four and five subtypes, separately; and the rest of the studies examined six or more types of risk factors, including one that considered 11 subtypes. The results provide base for performing association analysis.

Association analysis typically requires setting the minimum thresholds for support, confidence, and lift, which were set to 0.03, 0.5, and 1, respectively. The setting of threshold for minimum support considered the above-mentioned statistics of article count and the large number of risk factors (we did not exclude studies that examined only one subtype of risk factors for sake of ecological validity of our analysis results). The thresholds for confidence and lift were set based on commonsense. The analysis yielded a total of 40 association rules, and the top-21 rules are listed in Table 2 ranked in a descending order of lift. Take the first rule as an example for illustration. Among the research studies that investigated both polypharmacy and central nervous system agents as risk factors for ADE, half of them also considered the risk factor of cardiovascular agents. Additionally, compared with a randomly selected research study, investigating polypharmacy and central nervous system agents as risk factors for ADE in a research study boosted its chance of considering cardiovascular agents as a risk factor by 8 folds (lift = 8). We did not consider genetic factors in the association analysis mainly due to its small number of studies in relation to the large number of subtypes.

Severity, prevalence, and preventability of ADE

Among the reviewed studies, 67% reported the prevalence rate of ADE. The median prevalence rate was 19.5% (0.29%~86.2%). Highest prevalence rates of ADE were reported for MDR-TB patients (72.4%) [64], HIV-infected patients ≥ 18 years (86%) [86], and patients with HIV infection who completed IFN-based treatment (86.2%) [92]. In contrast, lowest prevalence rates were found in patients who had an indication for the scan and use of the contrast medium Ultravist-370 or Isovue-370 (0.31%) [42], patients from psychiatry department (0.69%) [88], and hospitalized patients (0.29~0.36%) [68, 95].

There were 19% of the selected studies that reported the preventability rate of ADE. The median preventability rate was 36.2% (2.63%~91%). Relatively high preventability rates of ADE were reported for hospitalized patients aged over 80 years old (63%) [104], adult patients visiting the tertiary care hospital (81.57%) [47], and children admitted to a medical ward (less than18 years) (81.7%) [93]. In contrast, HIV/AIDs patients who had been taking anti-retroviral treatment had very low preventability rate (2.63%) [114].

Among the selected studies, 29% reported the severity rate. The median severity rate was 16% (0.01%~47.4%). The highest severity rates were reported for ADE such as adverse events induced by ceftriaxone (30%) [117], cutaneous drug reactions (34%) [68], and ADE to first-line antituberculous agents (28%) [70], and the number of off-level medication associated ADR (41.3%) [107].

Characteristics of methods

About 94% of the reviewed studies used clinical trial data, and the remaining 6% studies drew data from databases such as Eclipsys Sunrise (EPSI), IPC, FDA Online Label Repository, Swedish national database of spontaneously reported ADRs, and Pittsburgh Medical Center–Presbyterian Hospital (UPMC-P) ADE. The elderly population accounted for one-fifth (19%) of the selected studies on risk factors for ADE. About 10% of selected studies used adults and children as the patient population. About 86% studies reported sample size and the median sample size was 595 (14~2,578,336). A diverse set of research types was employed by the selected studies, including 28% prospective study, 19% retrospective study, and 17% case-control study. The research studies conducted in hospital settings lasted between 4 weeks and 8 years, and the studies that used data from databases selected from 10 to 44 years’ worth of data.

The location where the selected studies were conducted spread across 33 countries, spanning six continents. They include North America (e.g., USA [30, 33, 39, 51, 54, 65, 67, 73, 74, 77, 78, 86, 107, 108, 132, 133] and Canada [26, 78, 128]), Europe (e.g., UK [38, 40, 45, 48, 50, 78, 104, 123], Germany [31, 45, 60, 61, 78, 99, 118], the Netherlands [27, 37, 57, 78, 81], Sweden [41, 90, 129, 131], France [59, 68, 106, 109], Italy [29, 63, 75, 83, 91, 97], Finland [25, 49], Norway [96], Ireland [32], Turkey [43], Portugal [35], Czech Republic [55], Spain [28, 92], Slovak Republic [89], and Switzerland [62]), Asia (e.g., China [42, 45, 66, 121], South Korea [53, 126, 127, 131], India [47, 56, 58, 69, 70, 76, 88, 102, 112, 114, 119, 134], Iran [87, 117], Thailand [79, 94], Taiwan [52, 82, 85, 95, 113], Vietnam [120], Japan [36, 84, 124, 125, 129], Pakistan [64], Hong Kong [45, 93], and Malaysia [45, 110]), Australia (e.g., Australia [45, 46, 78] and New Zealand [78]), South America (e.g., Brazil [72, 80, 100, 103, 111, 116] and Mexico [115]), and Africa (e.g., Ethiopia [44, 72]).

Discussion

The coverage of risk factors in this review is much broader and more in-depth than previous studies to better reflect the landscape of risk factors. Among the five main categories, health service-related risk factors are novel. Examples include poor coordination of care and length of hospital stay, which are potentially preventable and have practical implications for improving patient safety.

Genetic factors are identified as a separate category in this review. It has been long posited in pharmacogenetics that specific generic factors contribute to pharmacology [135]. However, only until recent years have many genetic discoveries been made owing to the drastic reduction in the cost of sequencing technologies. Genome-wide association studies [136] have fueled the search for genetic basis of disease susceptibility. The distinct characteristics and analysis methods of genetics factors separate them apart from other types of risk factors for ADE.

The two-level scheme provides an unprecedentedly fine-grained categorization of risk factors for ADE. Among the subtypes of risk factors, some have been under explored such as treatment compliance, concentrative nucleoside transporter, glycosyltransferase 29 family, VKOR, ETS transcription factor, peptidase M13, serine hydrolase enzyme, weight, lower respiratory diseases, disease complexity, metabolic agents, and gastrointestinal drugs. The results of this study show that the elderly population has been the focus of ADE study possibly due to their high vulnerability to ADE [137]. Additionally, patient with certain disease conditions such as genitourinary system disorders, circulatory system diseases and immunodeficiency, and blood diseases are highly susceptible to ADE. There are also potential gender differences in susceptibility to ADE [138,139,140]. For instance, females can be at a higher risk for ADE than their male counterparts possibly due to gender-associated differences in drug exposure. Furthermore, polypharmacy being the most frequently reported risk factor suggests that drug-drug interaction is a major risk for ADE. Interestingly, this review found that inappropriate use or change of drugs is another common subtype of medication-related risk factors, which is potentially preventable. The association analysis of risk factors contribute towards a fuller understanding of the complexity and interactions of risk factors by uncovering a number of interesting co-occurrence patterns of risk factors.

-

Cardiovascular agents and central nervous system agents commonly appear in the same research studies. The chance of simultaneous investigation of the two types of risk factors is even higher when polypharmacy is considered.

-

Age, gender, polypharmacy, and comorbidity are common and interacting themes across previous studies of risk factors for ADE. In addition, age is likely incorporated into the investigation of risk factors related to digestive system disorders, lifestyle, cardiovascular agents, and central nervous system agents; gender is likely considered in studies of ethnic group and circulatory system diseases as risk factors; and comorbidity is considered in studies of service utilization factors.

-

Polypharmacy is studied not only along with other common risk factors (e.g., age) but also along with other infrequently studied risk factors such as socioeconomic status and psychotherapeutic agents.

-

Some of the association rules achieved the perfect confidence score (i.e., 1) and extremely high lift values (> 30). For instance, studies examining digestive system disorders, or age, and lifestyle as risk factors, also considered gender with no exception. Polypharmacy was always included while studying gender and comorbidity or socioeconomic status as risk factors. If we lower the minimum threshold for support to 0.02, we would be able to identify another 63 association rules that have the perfect confidence score (= 1). For instance, gender and digestive system disorders were always examined along with lower respiratory diseases as risk factors; and gender and cardiovascular agents were always considered along with age and lifestyle as risk factors.

This study reveals contradicting findings about risk factors. Take the three most frequently studied risk factors (see Fig. 2) as examples. Despite that polypharmacy is a frequently reported risk factor, it was not found to be a risk factor for elderly patients admitted to the Emergency Department [41]. Age was reported as a risk factor for adult patients in some studies [30, 32], but not in others [119]. The majority of studies reported female [29, 31, 35, 39, 40, 42, 43, 47, 55,56,57,58,59,60,61], but some studies found male [34, 36, 62] as a risk factor. Therefore, the interpretations of the findings should be made with respect to specific patient population or conditions.

The results of this study reveal several issues related to risk factors for ADE that have been under studied.

-

Genetic factors. Genetic risk factors of ADE hold a great promise for personalized or precision medicine. As the technologies for genome sequencing and for performing large-scale analysis of gene expressions become more cost-effective, they will enable the discovery of pharmacogenomic markers and molecular pathways of ADE.

-

Mental health and wellness. It can be an important subtype of patient-related risk factors because there is a close connection between our mental and physical health, and our body responds to the way we think, feel, and act. Depression has been reported as a risk factor for ADE in several studies [67, 89, 91]. Other mental health-related problems such as stress and anxiety may cause high blood pressure, back pain, and chest pain, which are potential risk factors.

-

Education level. The education level of patients can have potential impacts on their awareness of ADE and adherence to medication interventions. However, education below high school as a risk factor has only been considered in one study [56]. General negative medication beliefs, reported as risk factor by one study [81], can be attributed to the lack of education.

-

Lifestyle. In addition to smoking and alcohol, patient’s lifestyle encompasses many other aspects such as unhealthy diet, lack of physical exercise, and lack of sleep, which may have a profound impact on patient’s health. One study shows that a large proportion of coronary patients do not achieve the lifestyle for cardiovascular disease prevention [141]. Physical exercise boosts metabolism and may help to reduce ADE. A challenging question is how to determine an appropriate type of lifestyle to avoid the harm of ADE.

-

Prevention. Avoiding risk factors could fundamentally mitigate ADE. Prevention may target different stages of medication administration, including prescription, dispensing, administration, and monitoring. Our findings show that inappropriate use or change of medications is a common subtype of risk factors and is preventable. In addition, computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support systems, ward-based clinical pharmacists, and improved communications among physicians, nurses, and pharmacists may prevent potential medication errors [142]. Clinicians should also consider the benefit of periodic systematic drug regimen reviews in an effort to reduce the occurrence ADE in older people [143].

-

Physical environment. The physical environment where patients reside such as climate, weather condition, and humidity could be associated with ADE. One primary way to draw such insights is by comparing patients across different countries and/or regions.

The list of specific risk factors for ADE included in this review is by no means complete. Their inclusion is limited by the coverage of selected databases of publications and the access to the full articles. For example, we reviewed only 15 studies on genetic risk factors. In addition, risk factors can vary with specific medication or disease condition. Furthermore, the review studies on risk factors typically did not differentiate specific ADE but only reported the percentage of ADE ([18, 19]). Differences also existed in the definition of severity of ADE across different studies.

Conclusion

ADE is subject to risk factors, and some are preventable. Risk factors can be categorized into five main categories, including patient, disease, medication, health service, and genetics. Among them, medication-related risk factors have been studied most frequently. Moreover, the most studied subtypes of risk factors include polypharmacy, age, gender, central nervous system agents, comorbidity, service utilization, inappropriate use/change use of drugs, cardiovascular agents, and anti-infectives. Among the subtypes, age, gender, polypharmacy, and comorbidity frequently appear in the same studies of risk factors for ADE. Each of the above subtypes is also frequently investigated along with various other types of risk factors. Cardiovascular agents and central nervous system agents are routinely considered in the same research studies of risk factors. Based on the two-level classification scheme of risk factors for ADE, this study suggests research issues related to risk factors that call for more future research. The findings of this study can be used to guide future studies in improving patient safety in care management by minimizing and preventing the harm of ADE.

References

Rozich JD, Haraden CR, Resar RK (2003) Adverse drug event trigger tool: a practical methodology for measuring medication related harm. Qual Saf Health Care 12(>3):194–200. https://doi.org/10.1136/qhc.12.3.194

Runciman WB, Roughead EE, Semple SJ, Adams RJ (2003) Adverse drug events and medication errors in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care 15(90001):i49–i59. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzg085

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, Farrar K, Park BK, Breckenridge AM (2004) Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ 329(7456):15–19. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.329.7456.15

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Petersen LA, Small SD, Servi D, Laffel G, Sweitzer BJ, Shea BF, Hallisey R et al (1995) Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE prevention study group. JAMA 274(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1995.03530010043033

Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS (2000) Errors in health care: a leading cause of death and injury

Willadsen TG, Bebe A, Køster-Rasmussen R, Jarbøl DE, Guassora AD, Waldorff FB, Reventlow S, Olivarius NF (2016) The role of diseases, risk factors and symptoms in the definition of multimorbidity—a systematic review. Scand J Prim Health Care 34(2):112–121. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2016.1153242

Nexøe J, Halvorsen PA, Kristiansen IS (2007) Review article: critiques of the risk concept—valid or not? Scand J Public Health 35(6):648–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940701418897

Reventlow S, Hvas AC, Tulinius C (2001) In Really great danger?. The concept of risk in general practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 19(2):71–75

Giorda CB, Nada E, Tartaglino B, Marafetti L, Gnavi RA (2014) Systematic review of acute pancreatitis as an adverse event of type 2 diabetes drugs: from hard facts to a balanced position. Diabetes Obes Metab 16(11):1041–1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.12297

Aronson JK (2013) Distinguishing hazards and harms, adverse drug effects and adverse drug reactions: implications for drug development, clinical trials, pharmacovigilance, biomarkers, and monitoring. Drug Saf 36(3):147–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-013-0019-9

Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Burke JP (1997) Adverse drug events in hospitalized patients: excess length of stay, extra costs, and attributable mortality. JAMA 277(4):301–306. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03540280039031

Porter J, Jick H (1977) Drug-related deaths among medical inpatients. JAMA 237(9):879–881. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1977.03270360041015

Hug BL, Keohane C, Seger DL, Yoon C, Bates DW (2012) The costs of adverse drug events in community hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 38(3):120–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(12)38016-1

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW (2003) The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 138(3):161–167. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007

Ernst FR, Grizzle AJ (2001) Drug-related morbidity and mortality: updating the cost-of-illness model. J Am Pharm Assoc (1996) 41(2):192–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1086-5802(16)31229-3

Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, Matthew Gladden R (2016) Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths—United States, 2000–2014. Am J Transplant 16(4):1323–1327. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13776

Alomar MJ (2014) Factors affecting the development of adverse drug reactions (review article). Saudi Pharm J 22(2):83–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2013.02.003

Kiguba R, Karamagi C, Bird SM (2017) Incidence, risk factors and risk prediction of hospital-acquired suspected adverse drug reactions: a prospective cohort of Ugandan inpatients. BMJ Open 7(1):e010568. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010568

Boeker EB, Ram K, Klopotowska JE, Boer M, Creus MT, Andrés AL, Sakuma M, Morimoto T, Boermeester MA, Dijkgraaf MGW (2015) An individual patient data meta-analysis on factors associated with adverse drug events in surgical and non-surgical inpatients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 79(4):548–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12504

Al Hamid A, Ghaleb M, Aljadhey H, Aslanpour ZA (2014) Systematic review of hospitalization resulting from medicine-related problems in adult patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 78(2):202–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12293

Resende LSO, Santos-Neto ET (2015) Risk factors associated with adverse reactions to antituberculosis drugs. J Bras Pneumol 41(1):77–89. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132015000100010

Stelzer G, Dalah I, Stein TI, Satanower Y, Rosen N, Nativ N, Oz-Levi D, Olender T, Belinky F, Bahir I, Krug H, Perco P, Mayer B, Kolker E, Safran M, Lancet D (2011) In-silico human genomics with GeneCards. Hum Genomics 5(6):709–717. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-7364-5-6-709

Piatetsky-Shapiro G (1991) Discovery, analysis, and presentation of strong rules. In: Piatetsky-Shapiro G, Frawley WJ (eds) Knowledge discovery in databases. AAAI/MIT Press, Cambridge

Hahsler M, Grün B, Hornik K (2005) arules-A computational environment for mining association rules and frequent item sets. J Stat Softw 14(15):1–25. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v014.i15

Härkänen M, Kervinen M, Ahonen J, Voutilainen A, Turunen H, Vehviläinen-Julkunen K (2015) Patient-specific risk factors of adverse drug events in adult inpatients–evidence detected using the global trigger tool method. J Clin Nurs 24(3-4):582–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12714

Mugoša S (2015) Adverse drug reactions in hospitalised cardiac patients: risk factors. Vojnosanit Pregl 72(11):975–981. https://doi.org/10.2298/VSP140710104M

Van den Bemt P, Egberts ACG, Lenderink AW, Verzijl JM, Simons KA, Van der Pol W, Leufkens HGM (2000) Risk factors for the development of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Pharm World Sci 22(2):62–66. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008721321016

Pedrós C, Quintana B, Rebolledo M, Porta N, Vallano A, Arnau JM (2014) Prevalence, risk factors and main features of adverse drug reactions leading to hospital admission. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70(3):361–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-013-1630-5

Onder G, Pedone C, Landi F, Cesari M, Della Vedova C, Bernabei R, Gambassi G (2002) Adverse drug reactions as cause of hospital admissions: results from the Italian Group of Pharmacoepidemiology in the Elderly (GIFA). J Am Geriatr Soc 50(12):1962–1968. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50607.x

Friedman BW, Cisewski DH, Holden L, Bijur PE, Gallagher EJ (2015) Age but not sex is associated with efficacy and adverse events following administration of intravenous migraine medication: an analysis of a clinical trial database. Headache: J Head Face Pain 55(10):1342–1355. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12697

Zopf Y, Rabe C, Neubert A, Gassmann KG, Rascher W, Hahn EG, Brune K, Dormann H (2008) Women encounter ADRs more often than do men. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 64(10):999–1004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-008-0494-6

Bradbury F (2004) How important is the role of the physician in the correct use of a drug? An observational cohort study in general practice. Int J Clin Pract 58:27–32

Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Fiskio JM, Seger AC, So JW, Cook EF, Fukui T, Bates DW (2004) An evaluation of risk factors for adverse drug events associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Eval Clin Pract 10(4):499–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2003.00484.x

Minkowitz HS, Gruschkus SK, Shah M, Raju A (2014) Adverse drug events among patients receiving postsurgical opioids in a large health system: risk factors and outcomes. Am J Health Syst Pharm 71(18):1556–1565. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp130031

Macedo AF, Alves C, Craveiro N, Marques FB (2011) Multiple drug exposure as a risk factor for the seriousness of adverse drug reactions. J Nurs Manag 19(3):395–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01216.x

Shiozawa T, Tadokoro J-i, Fujiki T, Fujino K, Kakihata K, Masatani S, Morita S, Gemma A, Boku N (2013) Risk factors for severe adverse effects and treatment-related deaths in Japanese patients treated with irinotecan-based chemotherapy: a postmarketing survey. Jpn J Clin Oncol 43(5):483–491. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyt040

de Boer M, Boeker EB, Ramrattan MA, Kiewiet JJS, Dijkgraaf MGW, Boermeester MA, Lie-A-Huen L (2013) Adverse drug events in surgical patients: an observational multicentre study. Int J Clin Pharm 35(5):744–752. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-013-9797-5

Kongkaew C, Hann M, Mandal J, Williams SD, Metcalfe D, Noyce PR, Ashcroft DM (2013) Risk factors for hospital admissions associated with adverse drug events. Pharmacotherapy: J Hum Pharmacol Drug Ther 33(8):827–837. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1287

Lee JS, Yang J, Stockl KM, Lew H, Solow BK (2016) Evaluation of eligibility criteria used to identify patients for medication therapy management services: a retrospective cohort study in a Medicare advantage part D population. J Manag Care Specialty Pharm 22(1):22–30. 10.18553/jmcp.2016.22.1.22

Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Harrold LR, Rothschild J, DeBellis KR, Seger AC, Auger JC, Garber LA, Cadoret C, Fish LS (2004) Risk factors for adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(8):1349–1354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52367.x

Helldén A, Bergman U, von Euler M, Hentschke M, Odar-Cederlöf I, Öhlén G (2009) Adverse drug reactions and impaired renal function in elderly patients admitted to the emergency department. Drugs Aging 26(7):595–606. https://doi.org/10.2165/11315790-000000000-00000

Zhang B, Dong Y, Liang L, Lian Z, Liu J, Luo X, Chen W, Li X, Liang C, Zhang S (2016) The incidence, classification, and management of acute adverse reactions to the low-osmolar iodinated contrast media Isovue and Ultravist in contrast-enhanced computed tomography scanning. Medicine 95(12):e3170. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003170

Gülbay BE, Gürkan ÖU, Yıldız ÖA, Önen ZP, Erkekol FÖ, Baççıoğlu A, Acıcan T (2006) Side effects due to primary antituberculosis drugs during the initial phase of therapy in 1149 hospitalized patients for tuberculosis. Respir Med 100(10):1834–1842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.01.014

Admassie E, Melese T, Mequanent W, Hailu W, Srikanth BA (2013) Extent of poly-pharmacy, occurrence and associated factors of drug-drug interaction and potential adverse drug reactions in Gondar Teaching Referral Hospital, North West Ethiopia. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 4(4):183–189. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-4040.121412

Rashed AN, Wong ICK, Cranswick N, Tomlin S, Rascher W, Neubert A (2012) Risk factors associated with adverse drug reactions in hospitalised children: international multicentre study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 68(5):801–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-011-1183-4

Buchbinder R, Forbes A, Kobben F, Boyd I, Snow RM, McNeil JJ (2000) Clinical features of tiaprofenic acid (surgam) associated cystitis and a study of risk factors for its development. J Clin Epidemiol 53(10):1013–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00192-X

Geer MI, Koul PA, Tanki SA, Shah MY (2016) Frequency, types, severity, preventability and costs of adverse drug reactions at a tertiary care hospital. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 81:323–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vascn.2016.04.011

Thiesen S, Conroy EJ, Bellis JR, Bracken LE, Mannix HL, Bird KA, Duncan JC, Cresswell L, Kirkham JJ, Peak M (2013) Incidence, characteristics and risk factors of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized children—sa prospective observational cohort study of 6,601 admissions. BMC Med 11:1

Hartikainen S, Mäntyselkä P, Louhivuori-Laako K, Enlund H, Sulkava R (2005) Concomitant use of analgesics and psychotropics in home-dwelling elderly people-Kuopio 75+ study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 60(3):306–310. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02417.x

Bellis JR, Kirkham JJ, Thiesen S, Conroy EJ, Bracken LE, Mannix HL, Bird KA, Duncan JC, Peak M, Turner MA (2013) Adverse drug reactions and off-label and unlicensed medicines in children: a nested case? Control study of inpatients in a pediatric hospital. BMC Med 11:1

Sheth HS, Verrico MM, Skledar SJ, Towers AL (2005) Promethazine adverse events after implementation of a medication shortage interchange. Ann Pharmacother 39(2):255–261. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1E361

Chang H-M, Tsai H-C, Lee SS-J, Kunin C, Lin P-C, Wann S-R, Chen Y-S (2016) High daily doses of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole are an independent risk factor for adverse reactions in patients with pneumocystis pneumonia and AIDS. J Chin Med Assoc 79(6):314–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcma.2016.01.007

Kim KS, Moon A, Kang HJ, Shin HY, Choi YH, Kim HS, Kim SG (2016) Higher plasma bilirubin predicts veno-occlusive disease in early childhood undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with cyclosporine. World J Transplant 6(2):403–410. https://doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v6.i2.403

Prows CA, Zhang X, Huth MM, Zhang K, Saldaña SN, Daraiseh NM, Esslinger HR, Freeman E, Greinwald JH, Martin LJ (2014) Codeine-related adverse drug reactions in children following tonsillectomy: a prospective study. Laryngoscope 124(5):1242–1250. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.24455

Langerová P, Vrtal J, Urbánek K (2014) Adverse drug reactions causing hospital admissions in childhood: a prospective, observational, single-centre study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 115(6):560–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcpt.12264

Singh H, Kumar BN, Sinha T, Dulhani N (2011) The incidence and nature of drug-related hospital admission: a 6-month observational study in a tertiary health care hospital. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 2(1):17–20. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-500X.77095

Rodenburg EM, Stricker BH, Visser LE (2012) Sex differences in cardiovascular drug-induced adverse reactions causing hospital admissions. Br J Clin Pharmacol 74(6):1045–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04310.x

Harugeri A, Parthasarathi G, Ramesh M, Guido S, Basavanagowdappa H (2011) Frequency and nature of adverse drug reactions in elderly in-patients of two Indian medical college hospitals. J Postgrad Med 57(3):189–195. https://doi.org/10.4103/0022-3859.85201

Montastruc JL, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Bagheri H, Fooladi A (2002) Gender differences in adverse drug reactions: analysis of spontaneous reports to a regional Pharmacovigilance Centre in France. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 16(5):343–346. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1472-8206.2002.00100.x

Schwaab B, Katalinic A, Böge UM, Loh J, Blank P, Kölzow T, Poppe D, Bonnemeier H (2009) Quinidine for pharmacological cardioversion of atrial fibrillation: a retrospective analysis in 501 consecutive patients. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 14(2):128–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-474X.2009.00287.x

Zopf Y, Rabe C, Neubert A, Hahn EG, Dormann H (2008) Risk factors associated with adverse drug reactions following hospital admission. Drug Saf 31(9):789–798. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831090-00007

Bravo AER, Tchambaz L, Krähenbühl-Melcher A, Hess L, Schlienger RG, Krähenbühl S (2005) Prevalence of potentially severe drug-drug interactions in ambulatory patients with dyslipidaemia receiving HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor therapy. Drug Saf 28(3):263–275. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528030-00007

Gervasoni C, Meraviglia P, Landonio S, Baldelli S, Fucile S, Castagnoli L, Clementi E, Riva A, Galli M, Rizzardini G (2013) Low body weight in females is a risk factor for increased tenofovir exposure and drug-related adverse events. PLoS One 8(12):e80242. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080242

Ahmad N, Javaid A, Syed Sulaiman SA, Afridi AK, Zainab, Khan AH (2016) Occurrence, management, and risk factors for adverse drug reactions in multidrug resistant tuberculosis patients. Am J Ther. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000000421

Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Avorn J, McCormick D, Jain S, Eckler M, Benser M, Bates DW (2001) Risk factors for adverse drug events among nursing home residents. Arch Intern Med 161(13):1629–1634. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.161.13.1629

Shi W, Wang Y-M, Li S-L, Yan M, Li D, Chen B-Y, Cheng N-N (2004) Risk factors of adverse drug reaction from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in shanghai patients with arthropathy. Acta Pharmacol Sin 25(3):357–365

Chrischilles E, Rubenstein L, Van Gilder R, Voelker M, Wright K, Wallace R (2007) Risk factors for adverse drug events in older adults with mobility limitations in the community setting. J Am Geriatr Soc 55(1):29–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01034.x

Fiszenson-Albala F, Auzerie V, Mahe E, Farinotti R, Durand-Stocco C, Crickx B, Descamps V (2003) A 6-month prospective survey of cutaneous drug reactions in a hospital setting. Br J Dermatol 149(5):1018–1022. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05584.x

Shah R, Gajjar B, Desai S (2012) A profile of adverse drug reactions with risk factors among geriatric patients in a tertiary care teaching rural hospital in India. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol 2(2):113–122. https://doi.org/10.5455/njppp.2012.2.113-122.

Shinde KM, Pore SM, Bapat TR (2013) Adverse reactions to first-line anti-tuberculous agents in hospitalised patients: pattern, causality, severity and risk factors. Indian J Med Specialities 4(1):16–21

Bertulyte I, Schwan S, Hallberg P (2014) Identification of risk factors for carbamazepine-induced serious mucocutaneous adverse reactions: a case-control study using data from spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports. J Pharmacol Pharmacother 5(2):100–138. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-500X.130051

Abera W, Cheneke W, Abebe G (2016) Incidence of antituberculosis-drug-induced hepatotoxicity and associated risk factors among tuberculosis patients in Dawro Zone, South Ethiopia: a cohort study. Int J Mycobacteriol 5(1):14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmyco.2015.10.002

Li H, Shi Q (2015) Drugs and diseases interacting with cigarette smoking in US prescription drug labelling. Clin Pharmacokinet 54(5):493–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-015-0246-6

Chrischilles EA, VanGilder R, Wright K, Kelly M, Wallace RB (2009) Inappropriate medication use as a risk factor for self-reported adverse drug effects in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 57(6):1000–1006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02269.x

Lattanzio F, Laino I, Pedone C, Corica F, Maltese G, Salerno G, Garasto S, Corsonello A, Incalzi RA (2012) PharmacosurVeillance in the elderly care study G. Geriatric conditions and adverse drug reactions in elderly hospitalized patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13(2):96–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2011.04.006

Haile DB, Ayen WY, Tiwari P (2013) Prevalence and assessment of factors contributing to adverse drug reactions in wards of a tertiary care hospital, India. Ethiop J Health Sci 23(1):39–48

Green JL, Hawley JN, Rask KJI (2007) The number of prescribing physicians an independent risk factor for adverse drug events in an elderly outpatient population? Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 5(1):31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.004

Lu CY, Roughead E (2011) Determinants of patient-reported medication errors: a comparison among seven countries. Int J Clin Pract 65:733–740

Tuchinda P, Chularojanamontri L, Sukakul T, Thanomkitti K, Nitayavardhana S, Jongjarearnprasert K, Uthaitas P, Kulthanan K (2014) Cutaneous adverse drug reactions in the elderly: a retrospective analysis in Thailand. Drugs Aging 31(11):815–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-014-0209-x

Lopes LC, Silveira MS, de Camargo MC, de Camargo IA, Luz TCB, Osorio-de-Castro CG, Barberato-Filho S, del Fiol Fde S, Guyatt G (2014) Patient reports of the frequency and severity of adverse reactions associated with biological agents prescribed for psoriasis in Brazil. Expert Opin Drug Saf 13(9):1155–1163. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2014.942219

De Smedt RHE, Denig P, van der Meer K, Haaijer-Ruskamp FM, Jaarsma T (2011) Self-reported adverse drug events and the role of illness perception and medication beliefs in ambulatory heart failure patients: a cross-sectional survey. Int J Nurs Stud 48(12):1540–1550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.05.014

Hung S-I, Chung W-H, Liou L-B, Chu C-C, Lin M, Huang H-P, Lin Y-L, Lan J-L, Yang L-C, Hong H-S (2005) HLA-B* 5801 allele as a genetic marker for severe cutaneous adverse reactions caused by allopurinol. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102(11):4134–4139. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0409500102

Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, Mazzei B, Di Iorio A, Carbonin P, Incalzi RA (2005) Concealed renal failure and adverse drug reactions in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gerontol Ser A Biol Med Sci 60(9):1147–1151. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/60.9.1147

Komeda T, Ishii S, Itoh Y, Sanekata M, Yoshikawa T, Shimada J (2016) Post-marketing safety evaluation of the intravenous anti-influenza neuraminidase inhibitor peramivir: a drug-use investigation in patients with high risk factors. J Infect Chemother 22(10):677–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiac.2016.07.004

Chen Y-C, Fan J-S, Chen M-H, Hsu T-F, Huang H-H, Cheng K-W, Yen DH-T, Huang C-I, Chen L-K, Yang C-C (2014) Risk factors associated with adverse drug events among older adults in emergency department. Eur J Intern Med 25(1):49–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2013.10.006

Mok S, Minson Q (2008) Drug-related problems in hospitalized patients with HIV infection. Am J Health Syst Pharm 65(1):55–59. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp070011

Namazi S, Pourhatami S, Borhani-Haghighi A, Roosta S (2014) Incidence of potential drug-drug interaction and related factors in hospitalized neurological patients in two Iranian teaching hospitals. Iran J Med Sci 39(6):515–521

Patel TK, Bhabhor PH, Desai N, Shah S, Patel PB, Vatsala E, Panigrahi S (2015) Adverse drug reactions in a psychiatric department of tertiary care teaching hospital in India: analysis of spontaneously reported cases. Asian J Psychiatr 17:42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2015.07.003

Wawruch M, Zikavska M, Wsolova L, Kuzelova M, Kahayova K, Strateny K, Kristova V (2009) Adverse drug reactions related to hospital admission in Slovak elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 48(2):186–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2008.01.004

Bejhed RS, Kharazmi M, Hallberg P (2016) Identification of risk factors for bisphosphonate-associated atypical femoral fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw in a pharmacovigilance database. Ann Pharmacother 50(8):616–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/1060028016649368

Onder G, Penninx BWJH, Landi F, Atkinson H, Cesari M, Bernabei R, Pahor M (2003) Depression and adverse drug reactions among hospitalized older adults. Arch Intern Med 163(3):301–305. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.163.3.301

Masip M, Tuneu L, Pagès N, Torras X, Gallego A, Guardiola JM, Faus MJ, Mangues MA (2015) Prevalence and detection of neuropsychiatric adverse effects during hepatitis C treatment. Int J Clin Pharm 37(6):1143–1151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-015-0177-1

Rashed AN, Wilton L, Lo CCH, Kwong B, Leung S, Wong ICK (2014) Epidemiology and potential risk factors of drug-related problems in Hong Kong paediatric wards. Br J Clin Pharmacol 77(5):873–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12270

Indradat S, Veskitkul J, Pacharn P, Jirapongsananuruk O, Visitsunthorn N (2016) Provocation proven drug allergy in Thai children with adverse drug reactions. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol 34(1):59–64. 10.12932/AP0601.34.1.2016

Liao PJ, Shih CP, Mao CT, Deng ST, Hsieh MC, Hsu KH (2013) The cutaneous adverse drug reactions: risk factors, prognosis and economic impacts. Int J Clin Pract 67(6):576–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.12097

Fosnes GS, Lydersen S, Farup PG (2011) Constipation and diarrhoea-common adverse drug reactions? A cross sectional study in the general population. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 11:2

Salvi F, Rossi L, Lattanzio F, Cherubini A (2016) Is Polypharmacy an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes after an emergency department visit?. Intern Emerg Med 12(2):213–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1451-5

Roulet L, Ballereau F, Hardouin J-B, Chiffoleau A, Potel G, Asseray N (2014) Adverse drug event nonrecognition in emergency departments: an exploratory study on factors related to patients and drugs. J Emerg Med 46(6):857–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.11.124

Thuermann PA, Windecker R, Steffen J, Schaefer M, Tenter U, Reese E, Menger H, Schmitt K (2002) Detection of adverse drug reactions in a neurological department. Drug Saf 25(10):713–724. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200225100-00004

Varallo FR, Capucho HC, Planeta CS, Mastroianni PC (2011) Safety assessment of potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) use in older people and the factors associated with hospital admission. J Pharm Pharm Sci 14(2):283–290. 10.18433/J3P01J

Varallo FR, Capucho HC, da Silva Planeta C, de Carvalho Mastroianni P (2014) Possible adverse drug events leading to hospital admission in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Clinics 69(3):163–167. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2014(03)03

Saiyed MM, Lalwani T, Rana DI (2015) Off-label use a risk factor for adverse drug reactions in pediatric patients? A prospective study in an Indian tertiary care hospital. Int J Risk Saf Med 27:45–53

de Araújo Lobo MGA, Pinheiro SMB, Castro JGD, Momenté VG, Pranchevicius M-CS (2013) Adverse drug reaction monitoring: support for pharmacovigilance at a tertiary care hospital in Northern Brazil. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 14:1

Tangiisuran B, Davies JG, Wright JE, Rajkumar C (2012) Adverse drug reactions in a population of hospitalized very elderly patients. Drugs Aging 29(8):669–679. https://doi.org/10.2165/11632630-000000000-00000

Admassie E, Melese T, Mequanent W, Hailu W, Srikanth BA (2013) Extent of poly-pharmacy, occurrence and associated factors of drug-drug interaction and potential adverse drug reactions in Gondar Teaching Referral Hospital, North West Ethiopia. J Adv Pharm Technol Res 4:183

Olivier P, Bertrand L, Tubery M, Lauque D, Montastruc J-L, Lapeyre-Mestre M (2009) Hospitalizations because of adverse drug reactions in elderly patients admitted through the emergency department. Drugs Aging 26(6):475–482. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200926060-00004

Smithburger PL, Buckley MS, Culver MA, Sokol S, Lat I, Handler SM, Kirisci L, Kane-Gill SLA (2015) Multicenter evaluation of off-label medication use and associated adverse drug reactions in adult medical ICUs. Crit Care Med 43(8):1612–1621. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001022

Zandieh SO, Goldmann DA, Keohane CA, Yoon C, Bates DW, Kaushal R (2008) Risk factors in preventable adverse drug events in pediatric outpatients. J Pediatr 152(2):225–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.09.054

Trivalle C, Burlaud A, Ducimetière P, Group I (2011) Risk factors for adverse drug events in hospitalized elderly patients: a geriatric score. Eur Geriatr Med 2(5):284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurger.2011.07.002

Zyoud SH, Awang R, Sulaiman S, Azhar S, Al-Jabi SW (2011) N-acetylcysteine-induced headache in hospitalized patients with acute acetaminophen overdose. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 25(3):405–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-8206.2010.00831.x

Botelho LFF, Porro AM, Enokihara MMSS, Tomimori J (2015) Adverse cutaneous drug reactions in a single quaternary referral hospital. Int J Dermatol 55(4):e198–e203. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.13126

Singh PK, Kumar MK, Kumar D, Kumar P (2015) Morphological pattern of cutaneous adverse drug reactions due to antiepileptic drugs in eastern India. J Clin Diagn Res: JCDR 9(1):WC01–WC03. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2015/11701.5419

Yang CY, Dao RL, Lee TJ, Lu CW, Yang CH, Hung SI, Chung WH (2011) Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to antiepileptic drugs in Asians. Neurology 77(23):2025–2033. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823b478c

Anwikar SR, Bandekar MS, Smrati B, Pazare AP, Tatke PA, Kshirsagar NA (2011) HAART induced adverse drug reactions: a retrospective analysis at a tertiary referral health care center in India. Int J Risk Saf Med 23:163–169

Castelán-Martínez OD, Jiménez-Méndez R, Rodríguez-Islas F, Fierro-Evans M, Vázquez-Gómez BE, Medina-Sansón A, Clark P, Carleton B, Ross C, Hildebrand C (2014) Hearing loss in Mexican children treated with cisplatin. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 78(9):1456–1460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2014.06.007

Passarelli MCG, Jacob-Filho W, Figueras A (2005) Adverse drug reactions in an elderly hospitalised population. Drugs Aging 22(9):767–777. https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200522090-00005

Shalviri G, Yousefian S, Gholami K (2012) Adverse events induced by ceftriaxone: a 10-year review of reported cases to Iranian Pharmacovigilance Centre. J Clin Pharm Ther 37(4):448–451. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01321.x

Sachs B, Fischer-Barth W, Erdmann S, Merk HF, Seebeck J (2007) Anaphylaxis and toxic epidermal necrolysis or Stevens–Johnson syndrome after nonmucosal topical drug application: fact or fiction? Allergy 62(8):877–883. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01398.x

Jayarama N, Shiju K, Prabahakar K (2012) Adverse drug reactions in adults leading to emergency department visits. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 4:642–646

Nguyen DV, Chu HC, Nguyen DV, Phan MH, Craig T, Baumgart K, van Nunen S (2015) HLA-B* 1502 and carbamazepine-induced severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions in Vietnamese. Asia Pac Allergy 5(2):68–77. https://doi.org/10.5415/apallergy.2015.5.2.68

Jiang J, Tang Q, Feng J, Dai R, Wang Y, Yang Y, Tang X, Deng C, Zeng H, Zhao Y (2016) Association between SLCO1B1− 521T> C and− 388A> G polymorphisms and risk of statin-induced adverse drug reactions: A meta-analysis. SpringerPlus 5(1):1368. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2912-z

Sun D, Yu C-H, Liu Z-S, He X-L, Hu J-S, Wu G-F, Mao B, Wu S-H, Xiang H-H (2014) Association of HLA-B* 1502 and* 1511 allele with antiepileptic drug-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome in central China. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci 34:146–150

Daly AK, Donaldson PT, Bhatnagar P, Shen Y, Pe’er I, Floratos A, Daly MJ, Goldstein DB, John S, Nelson MR (2009) HLA-B* 5701 genotype is a major determinant of drug-induced liver injury due to flucloxacillin. Nat Genet 41(7):816–819. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.379

Kaniwa N, Saito Y (2013) The risk of cutaneous adverse reactions among patients with the HLA-A* 31: 01 allele who are given carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine or eslicarbazepine: a perspective review. Ther Adv Drug Saf 4(6):246–253. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042098613499791

Ozeki T, Mushiroda T, Yowang A, Takahashi A, Kubo M, Shirakata Y, Ikezawa Z, Iijima M, Shiohara T, Hashimoto K (2011) Genome-wide association study identifies HLA-A* 3101 allele as a genetic risk factor for carbamazepine-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions in Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet 20(5):1034–1041. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddq537

Kim S-H, Jee Y-K, Lee J-H, Lee B-H, Kim Y-S, Park J-S, Kim S-H (2012) ABCC2 haplotype is associated with antituberculosis drug-induced maculopapular eruption. Allergy, Asthma Immunol Res 4(6):362–366. https://doi.org/10.4168/aair.2012.4.6.362

Yi JH, Cho Y-J, Kim W-J, Lee MG, Lee JH (2013) Genetic variations of ABCC2 gene associated with adverse drug reactions to valproic acid in Korean epileptic patients. Genom Inform 11(4):254–262. https://doi.org/10.5808/GI.2013.11.4.254

Visscher H, Ross CJD, Rassekh SR, Barhdadi A, Dubé M-P, Al-Saloos H, Sandor GS, Caron HN, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC, Canadian Pharmacogenomics Network for Drug Safety, C (2011) Pharmacogenomic prediction of anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol 30(13):1422–1428. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.34.3467

Saruwatari J, Matsunaga M, Ikeda K, Nakao M, Oniki K, Seo T, Mihara S, Marubayashi T, Kamataki T, Nakagawa K (2006) Impact of CYP2D6* 10 on H1-antihistamine-induced hypersomnia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 62(12):995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-006-0210-3

Lee A-Y, Kim M-J, Chey W-Y, Choi J, Kim B-G (2004) Genetic polymorphism of cytochrome P450 2C9 in diphenylhydantoin-induced cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60(3):155–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-004-0753-0

Takeuchi F, McGinnis R, Bourgeois S, Barnes C, Eriksson N, Soranzo N, Whittaker P, Ranganath V, Kumanduri V, McLaren W, Holm L, Lindh J, Rane A, Wadelius M, Deloukas PA (2009) Genome-wide association study confirms VKORC1, CYP2C9, and CYP4F2 as principal genetic determinants of warfarin dose. PLoS Genet 5(3):e1000433. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1000433

Pare G, Kubo M, Byrd JB, McCarty CA, Woodard-Grice A, Teo KK, Anand SS, Zuvich RL, Bradford Y, Ross S (2013) Genetic variants associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema. Pharmacogenet Genomics 23(9):470–478. https://doi.org/10.1097/FPC.0b013e328363c137

Sadhasivam S, Zhang X, Chidambaran V, Mavi J, Pilipenko V, Mersha TB, Meller J, Kaufman KM, Martin LJ, McAuliffe J (2015) Novel associations between FAAH genetic variants and postoperative central opioid-related adverse effects. Pharmacogenomics J 15(5):436–442. https://doi.org/10.1038/tpj.2014.79

Misra UK, Kalita J, Nair PP (2010) Role of aspirin in tuberculous meningitis: a randomized open label placebo controlled trial. J Neurol Sci 293(1-2):12–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2010.03.025

Kalow W (1961) Unusual responses to drugs in some hereditary conditions. Can Anaesth Soc J 8:43–52

Manolio TA (2010) Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. N Engl J Med 363(2):166–176. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0905980

Denham MJ (1990) Adverse drug reactions. Br Med Bull 46(1):53–62. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072394

Batchelor JR, Welsh KI, Tinoco RM, Dollery CT, Hughes GR, Bernstein R, Ryan P, Naish PF, Aber GM, Bing RF, Russell GI (1980) Hydralazine-induced systemic lupus erythematosus: influence of HLA-DR and sex on susceptibility. Lancet (London, England) 1:1107–1109

Teplitz L, Igic R, Berbaum ML, Schwertz DW (2005) Sex differences in susceptibility to epinephrine-induced arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 46(4):548–555. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.fjc.0000179435.26373.81

Rees JL, Friedmann PS, Matthews JNS (1989) Sex differences in susceptibility to development of contact hypersensitivity to dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB). Br J Dermatol 120(3):371–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.1989.tb04162.x

Kotseva K, Wood D, De Backer G, De Bacquer D, Pyörälä K, Keil U, Group ES. EUROASPIRE III (2009) A survey on the lifestyle, risk factors and use of cardioprotective drug therapies in coronary patients from 22 European countries. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 16(2):121–137. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283294b1d

Fortescue EB, Kaushal R, Landrigan CP, McKenna KJ, Clapp MD, Federico F, Goldmann DA, Bates DW (2003) Prioritizing strategies for preventing medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. Pediatrics 111(4):722–729. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.111.4.722

Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Koronkowski MJ, Weinberger M, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Lewis IK (1997) Adverse drug events in high risk older outpatients. J Am Geriatr Soc 45(8):945–948. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb02964.x

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank one reviewer for her assistance in annotating a subset of research articles. The authors would also like to thank another reviewer who provided consultation for several subtypes of risk factors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LZ: data annotation and categorization; idea conceiving and study design; analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, revisions, and approval of the manuscript. AR: collection, management, annotation, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, revisions, and approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 196 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Rupa, A.P. Categorization and association analysis of risk factors for adverse drug events. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 74, 389–404 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2373-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-017-2373-5