Abstract

Purpose

Combined paracetamol and ibuprofen has been shown to be more effective than either constituent alone for acute pain in adults, but the dose-response has not been confirmed. The aim of this study was to define the analgesic dose-response relationship of different potential doses of a fixed dose combination containing paracetamol and ibuprofen after third molar surgery.

Methods

Patients aged 16 to 60 years with moderate or severe pain after the removal of at least two impacted third molars were randomised to receive double-blind study medication as two tablets every 6 h for 24 h of either of the following: two tablet, combination full dose (paracetamol 1000 mg and ibuprofen 300 mg); one tablet, combination half dose (paracetamol 500 mg and ibuprofen 150 mg); half a tablet, combination quarter dose (paracetamol 250 mg and ibuprofen 75 mg); or placebo. The primary outcome measure was the time-adjusted summed pain intensity difference over 24 h (SPID 24) calculated from the 100-mm VAS assessments collected over multiple time points for the study duration.

Results

Data from 159 patients were included in the analysis. Mean (SD) time-adjusted SPID over 24 h were full-dose combination 20.1 (18.0), half dose combination 20.4 (20.8), quarter dose combination 19.3 (20.0) and placebo 6.6 (19.8). There was a significant overall effect of dose (p = 0.002) on the primary outcome. Planned pairwise comparisons showed that all combination dose groups were superior to placebo (full dose vs. placebo p = 0.004, half dose vs. placebo p = 0.002, quarter dose vs. placebo p = 0.002). The overall effect of dose was also significant for maximum VAS pain intensity score (p = 0.048), response rate (p = 0.0094), percentage of participants requiring rescue (p = 0.025) and amount of rescue (p < 0.001). No significant dose effect was found for time to peak reduction in VAS or time to meaningful pain relief. The majority of adverse events recorded were of mild (52.75 %) or moderate (40.16 %) severity and not related (30.7 %) or unlikely related (57.5 %) to the study medication.

Conclusion

All doses of the combination provide safe superior pain relief to placebo in adult patients following third molar removal surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Multi-modal analgesia has the potential to enhance analgesia while limiting safety risks [1]. Although there are many analgesic options available, most have limitations. Paracetamol is a widely used analgesic that may not provide sufficient analgesia in some clinical situations. Increasing the dose of paracetamol above the maximum daily recommended dose of 4000 mg increases the risk of hepatic injury [2]. Combining paracetamol with an opioid increases its analgesic efficacy but similarly increases the possibility of adverse effects, dependence, and abuse due to the opioid component. Paracetamol combined with an opioid may also increase the risk of paracetamol toxicity if dosing is increased to achieve opioid effects. Children may be at increased risk of respiratory depression from codeine [3], and the elderly are pre-disposed to constipation due to decreased fluid intake and lack of mobility [4]. NSAIDs may provide superior analgesia to paracetamol at high doses but are not without risks. NSAIDs are associated with gastric bleeding, thromboembolic events and significant fetal risks particularly in the third-trimester [5], and recent regulatory guidance encourages NSAID treatment to be with the minimum dose for the shortest possible time period [6]. In older adults, chronic NSAID use increases the risk of peptic ulcer disease, acute renal failure and stroke/myocardial infarction, and exacerbates existing conditions such as hypertension or heart failure [7].

A fixed dose combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen has been developed to provide analgesia above its individual components without adding to the safety burden or risks of either drug when used at a higher dose. This combination has been previously shown to provide superior analgesia to either paracetamol or ibuprofen alone: The area under the curve of visual analogue scale (AUC VAS) pain intensity scores at rest for the combination (22.3) was significantly superior to paracetamol (33.0) and ibuprofen (34.8) (p values 0.007 and 0.03, respectively [8]. While the efficacy of the combination has been established, the dose-response relationship remains unclear. It is of clinical interest that the analgesic dose-response relationship of clinical doses of the combination are evaluated using a reliable and valid model of acute pain: the dental impaction model provides one such model [9–11]. This model relies on postsurgical pain generated following the removal of third molars and is both well validated and highly standardised [9–11]. The dental impaction model allows for the investigation of analgesic efficacy, onset of pain relief and duration of analgesia and has previously been used to evaluate the analgesic effect of paracetamol, NSAIDs, opioids and combination analgesics [9, 11, 12].

The objective of this study was to determine the analgesic dose-response relationship of the different doses of the combination and compare the analgesic efficacy of the different combination doses to placebo. This aim is of clinical relevance as overdosing and class-related adverse events may be prevented, particularly in vulnerable groups of patients.

Patients and methods

Ethical practises

Based on the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices, the study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committee (Northern Y Regional Ethics Committee, New Zealand) and was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12611000450910). All participants provided written informed consent prior to any screening or study-related procedures.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible participants were aged between 16 and 60 years old presenting to the study centres for extraction of two to four impacted third molar teeth, one of which being mandibular and requiring bone removal. Patients were included if they reached at least moderate pain, determined by a score of ≥40 mm on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS), within 6 h of completion of surgery.

Exclusion criteria included the use of any analgesics in 12 h before surgery, weight <50 kg, a history of hypersensitivity to NSAIDs, paracetamol or opioids, gastrointestinal disorders such as gastric ulceration, indigestion, stomach pain or bleeding, or taking medications known to interact with the study medications. Patients with a history of severe asthma, haemopoetic, renal or hepatic disease or immunosuppression, or participants with a neurological disorder affecting pain perception were also excluded. Women who were pregnant, possible pregnant or unwilling to provide a urine pregnancy test, were not eligible for enrolment.

Study design

This was a multi-centre double-blind, placebo-controlled randomised, parallel group, multiple dose trial. The study design included a screening period (30 days before first dose), surgical period, qualification period (up to 6 h after completion of surgery) and a double-blind treatment period of 24 h. Surgery was performed under general or local anaesthesia using standard short-acting agents such as lignocaine, bupivacaine, midazolam fentanyl and propofol at the discretion of the treating clinician.

Once eligibility was confirmed after surgery, participants were randomised in a 3:3:4:4 ratio to one of the four treatment groups: combination full dose (paracetamol 1000 mg + ibuprofen 300 mg), combination half dose (paracetamol 500 mg + ibuprofen 150 mg), combination quarter dose (paracetamol 250 mg + ibuprofen 75 mg) or placebo. The randomisation code was determined using a computer-generated sequence provided by an independent statistician and was stratified by baseline pain intensity (moderate pain [VAS 40–69 mm] or severe pain [VAS ≥70 mm]) and anaesthetic (general or local). Each participant was assigned a unique randomisation number, and the investigator was supplied with a set of sealed randomisation envelopes in the event it was necessary to break the code for a specific participant. Investigators, research nurses and participants were blinded to the allocation, and the randomisation code was not broken until the study data were checked and locked. Study medications were provided by the sponsor and were identical in appearance and packaging.

The first dose of study drug was self-administered under the supervision of a research nurse immediately following randomisation and then at six hourly intervals, during the 24-h study period (constituting a total of four doses). Participants were required to continue taking study medication during the double-blind study period, regardless of pain level or having taken rescue analgesia. Rescue analgesia (oxycodone, immediate release) was provided if participants required additional analgesia due to insufficiently controlled pain. Participants were required to remain at the study centre for up to 6 h after surgery to complete the two stopwatch procedure and then were discharged home. The study nurse maintained telephone contact with participants to facilitate study diary completion and monitor for adverse events.

Efficacy evaluations

The primary efficacy endpoint was the time-adjusted summed pain intensity difference (SPID), derived from the VAS pain intensity scores (0–100 mm) up to 24 h after the first dose of study medication. The secondary efficacy endpoints included maximum VAS pain intensity scores up to 24 h after first study dose, response rates (percentage of participants who achieved at least a 50 % reduction in baseline pain within 6 h of first study dose), time to peak reduction in VAS pain intensity following first study dose, time to perceptible and meaningful pain relief, amount of rescue medication used, time to rescue medication, percentage of participants requiring rescue medication and categorical global pain rating.

Participants rated their pain intensity using the 100-mm VAS pain intensity scale anchored with 0 = no pain and 100 = worst pain imaginable. At each assessment, participants rated their pain at rest. Assessments were made at baseline (prior to randomisation and first dose of study medication) then at 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 1 h, 1.5 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 5 h and 6 h after the first dose of study medication. Additional VAS pain intensity assessments were then measured approximately every 2 h (while awake) until the end of the double-blind study period. The time to perceptible and meaningful pain relief was recorded using the two stopwatch method. Two stopwatches were started immediately after the participant swallowed the second tablet of the first dose of the study drug (time 0). The participant was instructed to “Stop stopwatch 1 when you first feel any pain relief whatsoever. This does not mean you feel completely better, although you might, but when you first feel any relief in the pain you have now” (i.e., perceptible pain relief). “Stop stopwatch 2 when you feel the pain relief is meaningful to you” (i.e., meaningful pain relief). If the subject did not stop the stopwatches within 6 h of time 0 or took rescue medication before achieving perceptible or meaningful pain relief, the two stopwatch procedures were discontinued, and a time of 6 h was documented [13].

Participants who believed that they were experiencing inadequate pain relief were able to take rescue medication (oxycodone 5 mg, prn). There was no restriction on when rescue medication could be taken if the participant considered rescue medication necessary. The timing and amount of rescue medication were recorded. VAS pain intensity measurements were taken immediately before rescue medication and then as scheduled. At the end of the double-blind study period, or immediately before taking rescue, participants were asked to provide global categorical assessment of the pain relief provided by the study medication using a five-point scale: 1 = poor, 2 = fair, 3 = good, 4 = very good, and 5 = excellent.

Tolerability evaluations

Tolerability of the study medication was assessed from the spontaneously reported adverse events (AEs). After the occurrence of an AE but before unbinding, investigators assessed the relationship of the AE to the study drug. AEs were considered to be not related, unlikely related, possibly related, probably related or definitely related to the study medication.

Sample size estimation

Determination of sample size was based on the time-adjusted SPID pooled standard deviation (20 mm) and effects measured in a recent evaluation of combination paracetamol and ibuprofen in the same pain model [8]. A sample size of 30 participants per active group and 40 in the placebo group would give 80 % power to show a difference of 16 % in the time adjusted SPID with a two-tailed type 1 error rate of 0.05. Forty participants in the placebo and quarter dose group would allow a difference of 15 % in SPID to be detected as statistically significant (two-tailed α = 0.05) with 80 % power. This study was not powered to detect a significant difference between the different doses of study medication.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Efficacy analyses were conducted using the modified intention to treat (mITT) population defined as all randomised participants who had at least one dose of study medication and had at least one VAS assessment after study drug administration. Safety endpoints were analysed according to the actual treatment taken.

The primary endpoint was analysed using a general linear model that included the strata as covariates and the randomised group as a fixed factor. Continuous secondary efficacy endpoints were tested for significance using the same linear models as used for the primary endpoint, and categorical and ordinal secondary endpoints were compared between groups using chi-square tests and Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests, as appropriate. The time-to-event outcomes including time to peak reduction in VAS pain intensity following first study dose, time to perceptible and meaningful pain relief, and the time to rescue medication were compared between groups using log-rank tests. A p value of ≤0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. All endpoints were first tested for an overall effect of randomised group (dose), and if this achieved statistical significance, pairwise comparisons of each dose group to placebo were undertaken. Standard descriptive statistics using means, medians, ranges and 95 % confidence intervals were used to describe the levels and the differences between groups.

Results

Participant enrolment

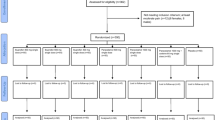

There were 159 participants randomised between August 2011 and October 2012. Participant recruitment, participation and attrition are outlined in Fig. 1. All 159 participants randomised received the first dose of the study medication and completed at least one VAS assessment and were eligible for the mITT analysis. Participant characteristics were adequately matched between groups at baseline (Table 1).

Analgesic effectiveness outcome analysis

Primary endpoint

The overall effect of dose on the time-adjusted SPID was statistically significant (p = 0.002). The change in VAS from baseline over the first dose interval is shown in Fig. 2. Subsequent pair-wise comparisons between the placebo group and each active treatment found all combination dose groups provided superior analgesic efficacy (mean time-adjusted SPID) compared to placebo (Table 2).

Secondary endpoints

The maximum VAS pain intensity score (p = 0.048), response rate (p = 0.009), time to requirement for rescue medication (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3), amount of rescue medication (p < 0.001) and percentage of participants requiring rescue medication (p = 0.025) all showed statistically significant differences among the dose groups. These secondary endpoints and the pairwise comparisons with placebo are presented in Table 3. Pairwise comparisons for these endpoints show that all combination dose groups were superior to placebo, except for the maximum VAS pain intensity score where only the full dose of the combination was superior to placebo (p = 0.009). No significant effect of combination doses was identified for the time to peak reduction in VAS (p = 0.634) or time to meaningful pain relief (p = 0.067).

There was a significant difference amongst the combination doses in terms of global pain relief (p = 0.006). Participants in the placebo group experienced the poorest global pain relief with pairwise comparisons showing that all combination doses were significantly better than placebo (Table 3).

Tolerability analysis

All randomised participants (n = 159) received at least one dose of the study drug and were included in the adverse effects evaluation. Table 4 summarises reported adverse events. Participants in the placebo group reported the most adverse events (40.8 %). The majority (56.4 %) of adverse events was gastrointestinal (GI) (e.g., nausea, vomiting and stomach discomfort). One serious adverse event was reported during the study (buccal infection in the half dose group), and this was considered to be unrelated to the study medication. No postoperative bleeding or thromboembolic events were reported.

Discussion

We found that all doses of the combination provided superior analgesia than placebo in the first 24 h after third molar surgery (Tables 2 and 3). The onset of analgesia was similar in all active treatment groups, with meaningful pain relief occurring at approximately 1.5–1.8 h. Meaningful pain relief was not achieved in the placebo group until 2.6 h after the first dose. The full-dose combination (1000 mg paracetamol and 300 mg ibuprofen) showed a significant reduction in maximum VAS pain intensity and higher response rate compared to placebo (mean (SD) 51.13 (13.22) vs. 61.20 (13.34); p = 0.009) (Table 3). The overall superiority of the combination to placebo is further reflected with the use of rescue medication: 81 % of participants in the placebo group required rescue medication compared to 56, 62 and 53 % of participants in the quarter, half and full-dose combination groups, respectively. The average time to the first dose of rescue medication was significantly longer in placebo groups than in the active treatment groups (Fig. 3). Those in the placebo group also required more rescue medication than those in the active treatment groups (Table 3).

Figure 2 shows a shallow dose-response curve for the quarter, half and full-dose combinations, which is in keeping with data on ibuprofen [14, 15]. Schou et al. noted in a single-dose trial that there was no significant difference in both pain intensity difference (SPID) or pain relief (TOTPAR) neither between 50 and 100 mg ibuprofen nor between 200 and 400 mg ibuprofen [14]. This was confirmed by a recent meta-analysis that found that the number-needed-to-treat (NNT) for at least 50 % pain relief compared with placebo for ibuprofen 200 mg was similar to that of ibuprofen 400 mg (2.7 vs. 2.5) [15].

This study also found that the combination was generally well tolerated and that the majority of adverse events that occurred across all the groups were gastrointestinal. This may be due to the oxycodone rescue medication, known for causing gastrointestinal disturbance, rather than the study medications.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Moderate-to-severe pain experienced after third molar extraction is an established, sensitive model for the assessment of analgesia. It is well accepted that the dental pain model is generalisable to other pain states: Postsurgical dental pain shares several pathophysiological elements with other painful conditions such as general postoperative pain and trauma [11], is a good predictor of analgesic effectiveness in other painful conditions [12] and is comparable and generalisable to other pain states such as general postsurgical, obstetric-gynaecological surgical and bunionectomy pain [9, 16]. In addition, patients requiring removal of third molars are usually otherwise healthy and rarely have confounding comorbidities. Using this model, we were able to clearly demonstrate the analgesic superiority of multiple doses of a fixed dose combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen compared to placebo.

Baseline pain intensity scores were relatively low in all groups (47.6–51.6 mm), and this may have limited the sensitivity of the trial thereby limiting the ability to separate the analgesic efficacy between combination doses. Consideration should be given to the sensitivity of the pain model used, particularly for dose-response trials. In addition, it should be noted that in accordance with regulatory guidance, this study was not powered to detect a difference between dose groups [17]. Nevertheless, this shallow dose-response curve suggests that the combination provides the flexibility to titrate dose in a community setting, which may further improve the tolerability of this combination.

Several methods exist for the determination of time to analgesic onset, but by far, the most accepted and reliable methods are the measurement of onset of meaningful pain relief using the two-stop watch method [5, 9]. This method relies on the participants’ interpretation of what meaningful pain relief is and when it occurs. In this study, all participants who required rescue were assigned a time to onset of 6 h. This attempt to ensure that the onset results were not biased by the use of rescue may be one reason why we were unable to show any difference in time to perceptible or meaningful pain relief between the study groups. Perhaps, another explanation is the participants’ understanding of meaningful pain relief, which in this study was not further defined—consideration should be given to the explanation and definitions of what constitutes meaningful pain relief to provide improved consistency to this measurement.

This study also has the advantage of being a multiple dose trial. Not limiting the assessment of analgesic effect to a single dose for an acute episode of postoperative pain provides further assurance that these study drugs provide sustained pain relief over a 24-h period.

Multimodal analgesia has the potential to enhance analgesia whilst simplifying dosing, increasing compliance and limiting safety risks [1]. Narcotic combinations are the most frequently prescribed postsurgical analgesics [18] but have a high incidence of the central nervous system-mediated adverse events such as drowsiness and nausea, while high-dose NSAIDs are associated with GI disorders. This study has shown that this fixed dose combination of paracetamol and ibuprofen is well tolerated and has good overall efficacy and that analgesia may be achieved with low-dose combination therapy.

References

Altman RD (2004) A rationale for combining acetaminophen and NSAIDs for mild-to-moderate pain. Clin Exp Rheumatol 22(1):110–117

Lee WM (2004) Acetaminophen and the U.S. Acute Liver Failure Study Group: lowering the risks of hepatic failure. Hepatol Baltim Md 40(1):6–9

Anderson BJ (2013) Is it farewell to codeine? Arch Dis Child 98:986–988

Herr K (2002) Chronic pain in ther older patient: management strategies. J Gerontol Nurs 28(2):28–34

Bloor M, Paech M (2013) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during pregnancy and the initiation of lactation. Anesth Analg 116(5):1063–1075

EMEA/CHMP/410051/2006. Opinion of the committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use Pursuant to Articles 5 (3) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004 FNN-s [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2010/01/WC500054342.pdf

Marcum ZA, Hanlon JT (2010) Recognizing the risks of chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in older adults. Ann Long Term Care Off J Am Med Dir Assoc 18(9):24

Merry AF, Gibbs RD, Edwards J, Ting GS, Frampton C, Davies E et al (2010) Combined acetaminophen and ibuprofen for pain relief after oral surgery in adults: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth 104(1):80–88

Cooper SA, Desjardins PJ (2010) The value of the dental impaction pain model in drug development. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ 617:175–190

Singla NK, Desjardins PJ, Chang PD (2014) A comparison of the clinical and experimental characteristics of four acute surgical pain models: dental extraction, bunionectomy, joint replacement, and soft tissue surgery. Pain 155(3):441–456

Urquhart E (1994) Analgesic agents and strategies in the dental pain model. J Dent 22(6):336–341

Nørholt SE (1998) Treatment of acute pain following removal of mandibular third molars. Use of the dental pain model in pharmacological research and development of a comparable animal model. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 27(Suppl 1):1–41

Desjardins P, Black P, Papageorge M, Norwood T, Shen DD, Norris L et al (2002) Ibuprofen arginate provides effective relief from postoperative dental pain with a more rapid onset of action than ibuprofen. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 58(6):387–394

Schou S, Nielsen H, Nattestad A, Hillerup S, Ritzau M, Branebjerg PE et al (1998) Analgesic dose-response relationship of ibuprofen 50, 100, 200, and 400 mg after surgical removal of third molars: a single-dose, randomized, placebo-controlled, and double-blind study of 304 patients. J Clin Pharmacol 38(5):447–454

Derry C, Derry S, Moore RA, McQuay HJ (2009) Single dose oral ibuprofen for acute postoperative pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3, CD001548

Barden J, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ, Andrew Moore R (2004) Pain and analgesic response after third molar extraction and other postsurgical pain. Pain 107(1–2):86–90

CPMP/ICH/378/95 (1994) Dose-response information to support drug registration E4. Dose-response. E4

RxList. The top 200 prescriptions by numbe rof US prescriptions dispensed [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jan 26]. Available from: http://www.rxlist.com/script/main/hp.asp

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to the participants who volunteered to take part in this research. We wish to thank Mr Christopher Seeley, Mrs Anneke Marais, Mrs Julia Matheson and Ms Ali Maoate for administration of the study protocol and data collection. We are grateful to Dr. Jennifer Zhang for trial monitoring, Dr. Amanda Potts for her assistance in drafting this manuscript and Mrs. Ioana Stanescu for reviewing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atkinson, H.C., Currie, J., Moodie, J. et al. Combination paracetamol and ibuprofen for pain relief after oral surgery: a dose ranging study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 71, 579–587 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1827-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-015-1827-x