Abstract

Touch spray-mass spectrometry (TS-MS) is an ambient ionization technique (ionization of unprocessed samples in the open air) that may find intraoperative applications in quickly identifying the disease state of cancerous tissues and in defining surgical margins. In this study, TS-MS was performed on fresh kidney tissue (∼1–5 cm3), within 1 h of resection, from 21 human subjects afflicted by renal cell carcinoma (RCC). The preliminary diagnostic value of TS-MS data taken from freshly resected tissue was evaluated. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the negative ion mode (m/z 700–1000) data provided the separation between RCC (16 samples) and healthy renal tissue (13 samples). Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) on the PCA-compressed data estimated sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) of 98 and 95 %, respectively, based on histopathological evaluation. The results indicate that TS-MS might provide rapid diagnostic information in spite of the complexity of unprocessed kidney tissue and the presence of interferences such as urine and blood. Desorption electrospray ionization-MS imaging (DESI-MSI) in the negative ionization mode was performed on the tissue specimens after TS-MS analysis as a reference method. The DESI imaging experiments provided phospholipid profiles (m/z 700–1000) that also separated RCC and healthy tissue in the PCA space, with PCA-LDA sensitivity and specificity of 100 and 89 %, respectively. The TS and DESI loading plots indicated that different ions contributed most to the separation of RCC from healthy renal tissue (m/z 794 [PC 34:1 + Cl]− and 844 [PC 38:4 + Cl]− for TS vs. m/z 788 [PS 36:1 − H]− and 810 [PS 38:4 − H]− for DESI), while m/z 885 ([PI 38:4 − H]−) was important in both TS and DESI. The prospect, remaining hurdles, and future work required for translating TS-MS into a method of intraoperative tissue diagnosis are discussed.

Touch spray-mass spectrometry used for lipid profiling of fresh human renal cell carcinoma. Left) Photograph of the touch spray probe pointed at the MS inlet. Right) Average mass spectra of healthy renal tissue (blue) and RCC (red)

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Kidney cancers cause a significant fraction of cancer-related fatalities in the USA, with 14,080 deaths and 61,560 new cases estimated in 2015 [1, 2]. Approximately 90 % of kidney cancers arise from the renal parenchyma and are termed renal cell carcinomas (RCC) [2]. RCC has been differentiated from normal tissue based on epigenetic [3, 4], genetic [5], proteomic [6–8], metabolomic [9, 10], and lipidomic markers [11, 12]. While these techniques are highly informative, analysis time is generally incompatible with intraoperative application, which is the long-term objective of this study. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry (MS), the MS analysis of samples in their native environment with little or no sample preparation, may improve surgical outcomes by providing surgeons with information that helps determine tissue disease state and identifies the tumor margin on the time scale of surgery. Previous intraoperative and/or ex vivo results from several investigators for brain cancer [13–16] and colon, lung, and liver cancers [17, 18] support this expectation. Moreover, it is known in several cancers that phospholipid profiles differ between tumor and normal tissues [19–21]. Lipids have been explored for recognizing cancerous tissue using a variety of ambient ionization techniques such as touch spray (TS) [22], probe electrospray ionization (PESI) [23], rapid evaporative ionization MS (REIMS) [17], and desorption electrospray ionization (DESI)-MS [24]. Lipids are of interest because of their roles in cell signaling, cell-cell recognition, immune response, energy metabolism, and malignant transformation of cells [25–27] and are expected to be reflective of disease state.

TS-MS involves the physical sampling of tissue using a metallic probe with subsequent ionization occurring directly from the probe upon the addition of solvent (1–2 μL) and high voltage (4–5 kV) (see Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. S1) [22, 28]. Free fatty acids and glycerophospholipids, including phosphatidylcholines (PCs) and phosphatidylinositols (PIs), are typically detected when performing TS-MS on frozen tissue sections [28]. TS-MS was previously used to analyze frozen sections of prostate cancer specimens from 18 human subjects, differentiating between normal prostate and prostate cancer [22]. However, TS-MS has not been used to study fresh in vitro tissue in a way that emulates possible intraoperative use. Like TS-MS, PESI-MS is an ambient ionization technique that uses a conductive metallic probe to sample tissue by puncturing it and then creating ions directly from the probe by application of high voltage [23, 29]. Yoshimura et al. analyzed fresh human RCC specimens with PESI in the positive ion mode and observed differences from normal tissue in phosphatidylcholine and triacylglycerol profiles [11]. PESI has also been used to analyze chemically induced hepatocellular carcinoma in a live mouse mounted on a sampling stage positioned in front of a mass spectrometer [30]. PESI and TS are both invasive techniques, but only small amounts of material (10–100 μg) are required to generate data. Both these techniques balance speed of analysis, degree of invasiveness, and amount of sample preparation such that they are amenable to intraoperative applications. An alternative technique, REIMS, samples ions directly from the surgical smoke produced by electrocauterization [17, 18, 31]. REIMS is a fast method because the surgical removal of tissue and mass spectrometric sampling are performed nearly simultaneously; however, the data are harder to correlate with traditional histopathology, the gold standard for diagnosis.

DESI-MS is a microprobe experiment in which a charged aerosol is sprayed onto a sample (e.g., a tissue section or smear) with a spot size of around 200 μm. The resulting thin liquid film formed on the sample surface dissolves some compounds, and subsequent droplet impacts produce splashes of charged analyte containing microdroplets. Gas-phase ions are generated via electrospray-like processes when the secondary microdroplets are sampled by the mass spectrometer [32]. DESI-MS imaging (DESI-MSI) experiments are performed by rastering the spot across the sample in a controlled fashion. An advantage of DESI-MSI when using an appropriate solvent is that the analyzed tissue can be stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) subsequent to MS analysis and evaluated by histopathology, enabling direct correlations to be drawn between molecular and morphological information [33]. DESI-MSI has been applied to analyze several malignancies [20, 21, 34, 35], including kidney cancers [12, 36], and demonstrated that the detected ions were reliably indicative of disease state (viz., distinction between tumor and normal tissues) via multivariate statistics. Finally, although not an ambient ionization technique, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-mass spectrometry has been performed in an imaging format, and it can also be used to profile tissue specimens, but the technique requires additional sample manipulation and it takes longer to analyze biopsy specimens [37–39].

In this study, TS-MS was used to analyze fresh healthy renal tissue and RCC specimens. As a reference method, DESI-MSI was performed following TS-MS analysis because DESI has been studied in more detail (DESI was first used to analyze tissue sections in 2005 [24], and TS was developed in 2014 [28]) and because measured DESI-MS lipid profiles can be precisely correlated with histopathological information by staining the analyzed tissue after DESI-MSI. Previous DESI-MSI studies of RCC in the negative ionization mode indicated the ability to differentiate RCC and healthy renal tissue with multivariate statistics, including the ability to differentiate clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) and papillary RCC [12]. Based on this previous work, we chose to perform the data acquisition in the negative ionization mode. This study focuses on the rapid analysis of fresh renal tissue using TS-MS with supporting DESI-MSI analysis.

Materials and methods

Tissue handling

All tissue samples were acquired from patients undergoing nephrectomy (partial or radical) for the treatment of RCC and were handled in accordance with approved Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocols at Indiana University School of Medicine (1205008669) and Purdue University (1203011967). A small portion (approximately 3 × 3 × 3 mm) of tumor and adjacent normal kidney tissue was taken from the biopsy in the pathology lab (University Hospital, Indianapolis, IN) and analyzed on-site using TS-MS. TS-MS analysis was performed while the tissue was fresh (not frozen or fixed). Subsequent to TS-MS analysis, the biopsy specimens were snap frozen in liquid N2 and transported back to Purdue University on dry ice for DESI-MSI analysis. Tissue samples were obtained from 21 subjects over the period of 1 year. Of the 21 cancer subjects, there were 15 with clear cell RCC, 2 with papillary RCC, 3 with unclassified RCC, and 1 with oncocytoma (see Table S1).

TS-MS analysis of freshly resected kidney tissue

On each day of surgery, the pathology laboratory at University Hospital notified the Purdue researchers when tissue was acquired from the operating room. The researchers transported the tissue specimens from the pathology laboratory to the linear trap quadrupole (LTQ) mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA) located in an adjacent research building. TS-MS was performed on the fresh (not frozen or fixed) tissue specimens using a metal teasing needle purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA) to scrape small amounts of cellular material from the bulk tissue [22]. The probe was positioned in front of the mass spectrometer with the metal tip pointing at the inlet (∼5–8 mm), a high voltage (4 kV) was applied, and a 1-μL aliquot of methanol was added to initiate ionization. Data were collected over the range m/z 200–1000 in the negative ionization mode. A chronogram showing the time dependence of a typical TS-MS signal recorded from a single solvent addition is shown in Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. S2. After TS-MS analysis at Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM), the tissue specimens were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen to preserve morphology and halt biochemical processes. The samples were then transported to Purdue for subsequent cryosectioning and DESI-MSI analysis. Parameters for MS/MS experiments which used an LTQ mass spectrometer and exact mass measurements using an orbitrap (Thermo Exactive, San Jose, CA), as well as additional methods on data handling, are provided in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

DESI-MS analysis of frozen tissue sections

At Purdue, the samples from each case were embedded in an optimal cutting temperature polymer (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and sectioned on a cryotome FSE to 10 μm thickness and thaw mounted on glass slides (Gold Seal UltraFrost Frosted Glass Slides, Thermo Scientific, San Jose, CA). Tumor and normal specimens (as determined by gross analysis performed in the pathology lab at IUSM) from each case were thaw mounted adjacent to each other on the same glass slide. A custom-built DESI source, similar to the DESI 2D source available from Prosolia Inc. (Indianapolis, IN), was used to image the tissue [40]. DESI spray solvent of dimethylformamide (DMF)-acetonitrile (ACN) 1:1 was used to minimize alteration of tissue morphology [33]. Additional DESI imaging and sample handling parameters are provided in the Electronic Supplementary Material. MS data were recorded over the range m/z 200–1000 in the negative ion mode, automatic gain control (AGC) was turned off, and data were acquired in the profile mode. The tissue sections were stained with H&E after DESI-MSI. A pathologist (L.C.) determined regions of healthy renal tissue and RCC. The DESI imaging data were compiled into a data cube using an in-house program. Data format was compatible with BioMap software (free to download at http://www.imzml.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=14&Itemid=32).BioMap and was used to extract mass spectra from regions of interest (ROIs) representing RCC and healthy renal tissue based on the histopathological examination (see Fig. S3).

Histological and pathological data

The pathology lab at IUSM performed histopathological analyses on the remaining tissue after providing the specimens to researchers as discussed. The pathological status of the adjacent tissue as well as the histological subtype, both determined by the pathology lab at IUSM, were used to correlate disease status with TS-MS lipid profiles. De-identified clinical and pathological data are provided in Electronic Supplementary Material Table S1. In addition, the tissue sections analyzed by DESI-MSI were subsequently stained with H&E and interpreted by a pathologist (L.C.) to determine regions of healthy tissue and RCC.

Statistical analyses of mass spectrometry data and data visualization

Principal component analysis (PCA), using the non-linear iterative partial least squares algorithm, on the TS-MS and DESI-MSI data was performed using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and in-house routines which were described in previous work [41]. Data were normalized using standard normal variate transformations to correct for baseline shifts and global variation in signal intensities. While data were recorded over the range m/z 200–1000, only the range m/z 700–1000 was utilized for PCA and subsequent linear discriminant analysis (LDA), as this mass range provides better diagnostic information [35]. LDA on the PCA-compressed data was performed in MATLAB to discriminate between healthy renal tissue and RCC [42]. PCA-LDA was used to calculate sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (true negative rate) by means of cross validation (using n = 5 deletion groups, Table S2). This procedure is described in detail elsewhere [43]. The dispersion in relative ion intensity for a few ions was plotted as box and whisker plots using OriginPro 2016 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). Unpaired two-sample t tests of unequal variance and Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric tests were performed in OriginPro 2016 using the raw, unnormalized signal intensities (Table S3).

Results and discussion

PCA was performed on TS-MS data after standard normal variate (SNV) normalization and mean centering. The PCA score and loading plots are shown in Fig. 1A, B, respectively. The separation between RCC and healthy renal tissue is observed in the score plot. As seen in the loading plot (Fig. 1B), healthy renal tissue is more abundant in m/z 794 and 792 (tentatively identified as chlorinated adducts of PC 34:1 and PC 34:2, respectively) and RCC is more abundant in m/z 844 and 885 (tentatively identified as chlorinated PC 38:4 and deprotonated PI 38:4, respectively). These assignments are from MS/MS spectra of these ions, as well as exact mass data, which are shown in Electronic Supplementary Material Figs. S4 and S5. The increased abundance of PI 38:4 in tumor cells is supported by biochemical studies from other laboratories which observed the altered inositol phospholipid metabolism as a common downstream effect due to the activation of several oncogenes including src, met, trk, mos, raf, and ras [25, 44]. Differences in m/z abundances are apparent in the average mass spectra of healthy renal tissue and RCC shown in Fig. 1C, D, respectively. Cross validation of a discriminant model, LDA on the PCA-compressed data, was performed. The average sensitivity (true positive rate) was 98.7 % and the specificity (true negative rate) was 94.6 % using five deletion groups and five principal components. The preliminary sensitivity and specificity results are encouraging, and they warrant further investigations with larger sample sizes to establish and validate the method’s diagnostic capabilities. Additional PCA score and loading plots are shown in Fig. S6, and confusion matrices for the cross validation are shown in supplemental Table S2. The importance of additional ions in separating RCC from healthy renal tissue can be appreciated by examining the lower-order PCA score and loading plots shown in Fig. S6; additional information on interpreting PCA score and loading plots can be found in Pirro et al. [41]. The univariate statistical significance of several of these ions, including m/z 771, 788, 792, 794, 810, 816, 844, and 885, in differentiating tumor and normal tissues was evaluated with an unpaired two-sample t test of unequal variance and a Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric test (Table S3) and is being visualized with box and whisker plots (Fig. S7). An agreement was observed between the univariate tests for all tested m/z values. The p value was <0.05 for each of the eight ions except for m/z 844 in which the null hypothesis (the mean value of each dataset originates from the same distribution) failed to be rejected.

Negative ion mode TS-MS results from the kidney surgical cases. A The PCA score plot of the TS-MS data. Each object represents a separate sampling ionization event from the freshly resected tissue. Healthy renal tissue is blue, and RCC is red. A total of 18 human subjects are represented, with 16 RCC and 13 healthy renal tissue specimens, respectively. The average sampling events per tissue is 5. B The corresponding PCA loading plot showing that m/z 792 ([PC 34:2 + Cl]−), 794 ([PC 34:1 + Cl]−), 844 ([PC 38:4 + Cl]−), and 885 ([PI 38:4 − H]−) are the major contributors to the separation observed in A. C, D Average mass spectra of the normal and tumor classes, respectively. The SNV-normalized signal intensity is plotted in the average spectra

Histopathological subtypes of the specimens were provided by the IUSM pathology lab, and additional PCA score and loading plot as well as average mass spectra are provided in Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. S8. The number of samples in each subtype was too small to comment on the ability of TS-MS to delineate RCC subtypes. Subtyping is a topic worth exploring further but is beyond the scope of this communication.

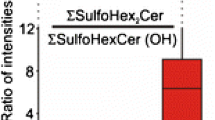

The results from the DESI-MSI experiments, used as a reference method to compare with the TS-MS results, are shown in Fig. 2. Similar but better separation is observed in the DESI-MSI PCA score plot (Fig. 2A); however, the DESI loading plot (Fig. 2B) is characterized by m/z 788 and 810 (tentatively deprotonated PS 36:1 and PS 38:4, respectively) and the same TS ion by m/z 885 (deprotonated PI 38:4). These ions (m/z 788, 810, and 885) are evident in the averaged spectra for RCC and healthy renal tissue shown in Fig. 2C, D. The significant contribution of m/z 810 is also observed in the TS-MS data in PC5 (see Electronic Supplementary Material Fig. S6E and F). Examples of H&E-stained tissue sections after DESI-MS analysis as well as a selection of DESI-MS ion images for specimens from three subjects are shown in Fig. S9. Additional PCA score and loading plots for the DESI-MS data are shown in Fig. S10. Cross validation was performed on the DESI PCA-LDA model in a fashion similar to the TS datasets. Using five deletion groups and three principal components, the average sensitivity was 100 % and the specificity was 88.9 % (Table S2). The difference in abundance of the type of ion detected (i.e., chlorinated adduct vs. deprotonated molecule) between TS and DESI can be attributed simply to differences in ionization mechanisms, increased biofluid content in the fresh tissue analyzed by TS-MS, and perhaps to the use of different spray solvents (methanol for TS and 1:1 DMF-ACN for DESI) [28, 33]. Relative to DESI, the greater contribution of chlorinated adducts in TS-MS is a previously reported phenomenon [28]. The difference between DESI and TS mass spectra suggests that future uses of TS as a diagnostic method will require the development of spectral databases (training sets) composed of TS-MS data.

Negative ion mode DESI-MSI results from the surgical kidney specimens. DESI-MSI on cryosectioned tissue was conducted after the TS-MS analysis on the fresh tissue. Samples from 20 human subjects are presented, with 16 RCC and 15 healthy renal tissue specimens, respectively. A The PCA score plot of the DESI-MSI data. Each object represents a mass spectrum obtained from a ROI of a single tissue specimen. Healthy renal tissue is blue, and RCC is red. B The corresponding loading plot for the score plot in A, showing contributions of m/z 788 ([PS 36:1 − H]−), 810 ([PS 38:4 − H]−), and 885 ([PI 38:4 − H]−) in the separation observed in the score plot. C, D The average SNV-normalized DESI mass spectra of the healthy renal tissue and RCC classes, respectively

The reported data suggest that TS-MS has the potential to yield diagnostic chemical information from fresh healthy renal tissue and RCC tissue. Prior to undertaking a large-scale study, a TS-MS ionization source equipped with microcontrollers for precise probe manipulation and an automated solvent delivery system should be designed and optimized to increase data quality and reproducibility. While the TS-MS experiments were conducted on tissue after resection from a human subject, the analysis occurred on the intraoperative time scale. The results support larger-scale studies of ex vivo surgical tissue using TS-MS to generate a comprehensive database of RCC specimens.

Additional aspects worth investigating are tumor heterogeneity and tumor margins. Ideally, the short analysis time and minimal invasiveness of TS-MS suggest that it might be used to profile various regions within the tumor mass itself and in the surrounding parenchyma. It would be interesting to investigate how the TS-MS lipid profiles (e.g., molecular information) vary within the tumor, as it has been shown that the extent of tumor heterogeneity is underestimated because of limitations in the number of samples that can be obtained [45, 46]. Additionally, TS-MS may aid in delineation of the tumor-parenchyma margin (i.e., tumor margin) in partial nephrectomies, as the utility of intraoperative frozen section analysis remains controversial [47]. This would be beneficial because negative parenchymal surgical margins of any size (e.g., less than 1 mm) for localized, low-grade (T1) RCC have been shown to result in virtually 0 % recurrence of the disease [48, 49].

Conclusions

This preliminary study demonstrated the feasibility of TS-MS analysis on a small number of fresh ex vivo surgical tissue specimens, as an intermediate step between frozen tissue analysis and intraoperative analysis. TS-MS differentiation of specimens using PCA and LDA was demonstrated, and the ions of greatest importance for separation were tentatively identified as complex membrane phospholipids m/z 794 (PC 16:0–18:1), 885 (PI 38:4), and 844 (PC 38:4). Differentiation of RCC and normal specimens was readily achieved by TS-MS and DESI-MS, although different ions were important for the separation between the two methods. Future work aims to expand the number of specimens in order to validate diagnostic capabilities, and further study the analytical figures of merit of the TS-MS methodology. The applicability of the technique is likely not exclusive to renal cell carcinomas, and it would be fruitful to investigate TS-MS in other cancers. In addition, refinements to the TS-MS methodology should be pursued to increase the ruggedness, ease of use, accuracy, and reproducibility of the measurements.

References

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, et al. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2012. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2015.

Chow WH, Dong LM, Devesa SS. Epidemiology and risk factors for kidney cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7(5):245–57.

Lasseigne BN, Burwell TC, Patil MA, Absher DM, Brooks JD, Myers RM. DNA methylation profiling reveals novel diagnostic biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Med. 2014;12:235.

Liao L, Testa JR, Yang H. The roles of chromatin-remodelers and epigenetic modifiers in kidney cancer. Cancer Genet. 2015;208(5):206–14.

Durinck S, Stawiski EW, Pavia-Jimenez A, Modrusan Z, Kapur P, Jaiswal BS, et al. Spectrum of diverse genomic alterations define non-clear cell renal carcinoma subtypes. Nat Genet. 2014;47(1):13–21.

Masui O, White NM, DeSouza LV, Krakovska O, Matta A, Metias S, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis in metastatic renal cell carcinoma reveals a unique set of proteins with potential prognostic significance. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;12(1):132–44.

Morgan TM, Seeley EH, Fadare O, Caprioli RM, Clark PE. Imaging the clear cell renal cell carcinoma proteome. J Urol. 2012;189(3):1097–103.

Guo T, Kouvonen P, Koh CC, Gillet LC, Wolski WE, Rost HL, et al. Rapid mass spectrometric conversion of tissue biopsy samples into permanent quantitative digital proteome maps. Nat Med. 2015;21(4):407–13.

Ganti S, Weiss RH. Urine metabolomics for kidney cancer detection and biomarker discovery. Urol Oncol. 2011;29(5):551–7.

Monteiro MS, Carvalho M, Bastos ML, Pinho PG. Biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma: a metabolomics approach. Metabolomics. 2014;10:1210–22.

Yoshimura K, Chen LC, Mandal MK, Nakazawa T, Yu Z, Uchiyama T, et al. Analysis of renal cell carcinoma as a first step for developing mass spectrometry-based diagnostics. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(10):1741–9.

Dill AL, Eberlin LS, Zheng C, Costa AB, Ifa DR, Cheng L, et al. Multivariate statistical differentiation of renal cell carcinomas based on lipidomic analysis by ambient ionization imaging mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2010;398(7–8):2969–78.

Santagata S, Eberlin LS, Norton I, Calligaris D, Feldman DR, Ide JL, et al. Intraoperative mass spectrometry mapping of an onco-metabolite to guide brain tumor surgery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(30):11121–6.

Eberlin LS, Norton I, Orringer D, Dunn IF, Liu X, Ide JL, et al. Ambient mass spectrometry for the intraoperative molecular diagnosis of human brain tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(5):1611–6.

Schafer KC, Balog J, Szaniszlo T, Szalay D, Mezey G, Denes J, et al. Real time analysis of brain tissue by direct combination of ultrasonic surgical aspiration and sonic spray mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2011;83(20):7729–35.

Agar NY, Golby AJ, Ligon KL, Norton I, Mohan V, Wiseman JM, et al. Development of stereotactic mass spectrometry for brain tumor surgery. Neurosurgery. 2011;68(2):280.

Balog J, Sasi-Szabo L, Kinross J, Lewis MR, Muirhead LJ, Veselkov K, et al. Intraoperative tissue identification using rapid evaporative ionization mass spectrometry. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5(194):194ra93.

Balog J, Kumar S, Alexander J, Golf O, Huang J, Wiggins T, et al. In vivo endoscopic tissue identification by rapid evaporative ionization mass spectrometry (REIMS). Angew Chem Int Ed. 2015;54(38):11059–62.

Marien E, Meister M, Muley T, Fieuws S, Bordel S, Derua R, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer is characterized by dramatic changes in phospholipid profiles. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1539–48.

Eberlin LS, Gabay M, Fan AC, Gouw AM, Tibshirani RJ, Felsher DW, et al. Alteration of the lipid profile in lymphomas induced by MYC overexpression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(29):10450–5.

Ifa DR, Eberlin LS. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry for cancer diagnosis and surgical margin evaluation. Clin Chem. 2016;62(1):111–23.

Kerian KS, Jarmusch AK, Pirro V, Koch MO, Masterson TA, Cheng L, et al. Differentiation of prostate cancer from normal tissue in radical prostatectomy specimens by desorption electrospray ionization and touch spray ionization mass spectrometry. Analyst. 2015;140(4):1090–8.

Mandal MK, Saha S, Yoshimura K, Shida Y, Takeda S, Nonami H, et al. Biomolecular analysis and cancer diagnostics by negative mode probe electrospray ionization. Analyst. 2013;138(6):1682–8.

Wiseman JM, Puolitaival SM, Takáts Z, Cooks RG, Caprioli RM. Mass spectrometric profiling of intact biological tissue by using desorption electrospray ionization. Angew Chemie Int Ed. 2005;117(43):7256–9.

Alonso T, Morgan RO, Marvizon JC, Zarbl H, Santos E. Malignant transformation by ras and other oncogenes produces common alterations in inositol phospholipid signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(12):4271–5.

Chaurio RA, Janko C, Muñoz L, Frey B, Herrmann M, Gaipl U. Phospholipids: key players in apoptosis and immune regulation. Molecules. 2009;14(12):4892–914.

Ackerman D, Simon MC. Hypoxia, lipids, and cancer: surviving the harsh tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24(8):472–8.

Kerian KS, Jarmusch AK, Cooks RG. Touch spray mass spectrometry for in situ analysis of complex samples. Analyst. 2014;139:2714–20.

Mandal MK, Yoshimura K, Chen LC, Yu Z, Nakazawa T, Katoh R, et al. Application of probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (PESI-MS) to clinical diagnosis: solvent effect on lipid analysis. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23(11):2043–7.

Yoshimura K, Mandal MK, Hara M, Fujii H, Chen LC, Tanabe K, et al. Real-time diagnosis of chemically induced hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel mass spectrometry-based technique. Anal Biochem. 2013;441(1):32–7.

Balog J, Szaniszlo T, Schaefer KC, Denes J, Lopata A, Godorhazy L, et al. Identification of biological tissues by rapid evaporative ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2010;82(17):7343–50.

Takats Z, Wiseman JM, Gologan B, Cooks RG. Mass spectrometry sampling under ambient conditions with desorption electrospray ionization. Science. 2004;306:471–3.

Eberlin LS, Ferreira CR, Dill AL, Ifa DR, Cheng L, Cooks RG. Nondestructive, histologically compatible tissue imaging by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Chembiochem. 2011;12(14):2129–32.

Eberlin LS, Tibshirani RJ, Zhang J, Longacre TA, Berry GJ, Bingham DB, et al. Molecular assessment of surgical-resection margins of gastric cancer by mass spectrometric imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(7):2436–41.

Jarmusch AK, Pirro V, Baird Z, Hattab EM, Cohen-Gadol AA, Cooks RG. Lipid and metabolite profiles of human brain tumors by desorption electrospray ionization-MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(6):1486–91.

Shroff EH, Eberlin LS, Dang VM, Gouw AM, Gabay M, Adam SJ, et al. MYC oncogene overexpression drives renal cell carcinoma in a mouse model through glutamine metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(21):6539–44.

Calligaris D, Feldman DR, Norton I, Olubiyi O, Changelian AN, Machaidze R, et al. MALDI mass spectrometry imaging analysis of pituitary adenomas for near-real-time tumor delineation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(32):9978–83.

Prentice BM, Chumbley CW, Caprioli RM. High-speed MALDI MS/MS imaging mass spectrometry using continuous raster sampling. J Mass Spectrom. 2015;50(4):703–10.

Spraggins JM, Caprioli RM. High-speed MALDI-TOF imaging mass spectrometry: rapid ion image acquisition and considerations for next generation instrumentation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22(6):1022–31.

Bennet RV, Gamage CM, Fernandez FM. Imaging of biological tissues by desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J Vis Exp. 2013;77:e50575.

Pirro V, Eberlin LS, Oliveri P, Cooks RG. Interactive hyperspectral approach for exploring and interpreting DESI-MS images of cancerous and normal tissue sections. Analyst. 2012;137(10):2374–80.

Pirro V, Oliveri P, Ferreira CR, Gonzalez-Serrano AF, Machaty Z, Cooks RG. Lipid characterization of individual porcine oocytes by dual mode DESI-MS and data fusion. Anal Chim Acta. 2014;848:51–60.

González-Serrano AF, Pirro V, Ferreira CR, Oliveri P, Eberlin LS, Heinzmann J, et al. Desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry reveals lipid metabolism of individual oocytes and embryos. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e74981.

Alonso T, Santos E. Increased intracellular glycerophosphoinositol is a biochemical marker for transformation by membrane-associated and cytoplasmic oncogenes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;171(1):14–9.

Ricketts CJ, Linehan WM. Intratumoral heterogeneity in kidney cancer. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):214–5.

Gerlinger M, Horswell S, Larkin J, Rowan AJ, Salm MP, Varela I, et al. Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nat Genet. 2014;46(3):225–33.

Sterious SN, Simhan J, Smaldone MC, Tsai KJ, Canter D, Wameedh E, et al. Is there a benefit to frozen section analysis at the time of partial nephrectomy? Can J Urol. 2013;20(3):6778–84.

Sutherland SE, Resnick MI, Maclennan GT, Goldman HB. Does the size of the surgical margin in partial nephrectomy for renal cell cancer really matter? J Urol. 2001;167(1):61–4.

Lam JS, Bergman J, Breda A, Schulam PG. Importance of surgical margins in the management of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008;5(6):308–17.

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number R21EB015722. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. K. A. Kerian gratefully recognizes the funding support from the Purdue University Center for Cancer Research SIRG Graduate Research Assistantship Award that funded him for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The research involving human subjects was conducted in compliance with the ethical guidelines of the approved Institutional Review Board protocols at the Indiana University School of Medicine (study # 1205008669R004) and Purdue University (study # 1203011967). The renal cell carcinoma samples were obtained from 21 human subjects after they provided written informed consent to participate in the research study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 2287 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alfaro, C.M., Jarmusch, A.K., Pirro, V. et al. Ambient ionization mass spectrometric analysis of human surgical specimens to distinguish renal cell carcinoma from healthy renal tissue. Anal Bioanal Chem 408, 5407–5414 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-016-9627-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-016-9627-4