Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Urinary tract infection is the most common complication after urodynamic studies (UDS). Practice guidelines recommend against antibiotic prophylaxis based on an outdated review of the literature, which advised on the premise of “a lack of good quality studies” and based on an assumed low incidence not consistently supported by the literature.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to update the assessment of the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis compared with placebo or no treatment for prevention of urinary tract infection in females over the age of 18 years undergoing UDS.

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, COCHRANE, DISSERTATIONS, conference proceedings and clinical trial registries were searched for relevant randomized controlled trials. Two authors independently screened and selected articles, assessed these for quality according to Cochrane guidelines and extracted their data.

Results

A total of 2633 records were screened, identifying three relevant randomized controlled trials. The one study that was critically appraised as being the least likely biased showed a statistically significant effect of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing bacteriuria post UDS in female patients. The other two studies included in the review did not. None of the studies included were powered to show a significant change in the incidence of urinary tract infection following UDS in female patients receiving antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis.

Conclusions

Similar to the 2012 Cochrane review on this subject, this systematic review demonstrated that antibiotic prophylaxis may decrease bacteriuria in women post UDS; however, further research is required to assess its effect on urinary tract infections in this context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A urodynamic study (UDS) is a widely used diagnostic tool for the evaluation of female lower urinary tract dysfunction [1]. Urinary tract infection (UTI) is the most common complication associated with UDS, as the required urethral catheterization may cause tissue damage and the introduction of external pathogens [2]. Incidence estimates of UTI following UDS vary widely; however, the literature reports rates as high as 28% [3]. The specific risk factors identified in the literature include older age, elevated BMI, being multiparous, hypothyroidism, diabetes, advanced pelvic organ prolapse, previous surgery for treatment of incontinence and UTI before urodynamic investigation [2, 4, 5].

Prophylactic measures often taken to prevent UTI after UDS include appropriate patient selection, pre-procedure urine culture screening, antiseptic urethral meatal cleaning and medical prophylaxis with antibiotics. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) June 2018 practice bulletin did not, however, recommend routine antibiotic prophylaxis for women undergoing UDS [6]. This decision was based on a 2012 Cochrane review that stated the benefit of prophylactic antibiotic use in reducing symptomatic UTI after UDS was still unclear based on “a lack of good quality studies and the need for robustly conducted and sufficiently powered randomized controlled trials” [7]. Conversely, the Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada (SOGC) 2018 reaffirmed practice guideline endorsed antibiotic prophylaxis but only when the incidence of UTI following UDS was found to be > 10% in the patient population of interest [3, 8]. Remarkably, this recommendation was based on a study that was authored by one of the guideline authors and was made despite the poorly established variable rates of incidence and limited scientific evidence, particularly in female patients. No societal recommendations exist based on female-specific literature. In fact, no systematic reviews exist on this topic based purely on female data, surprisingly given that many of the risk factors for UTI following UDS and cystoscopy are associated with patients being female.

Anecdotally, we find physicians each weigh the risks of a UTI post UDS against the risks of prophylactic antibiotics (such as increased microbial resistance patterns [9]), and there is no consensus on when prophylactic antibiotics are warranted. In this study, we aim to update the 2012 Cochrane review and present the first female-specific systematic review with the primary objective of evaluating the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis compared with placebo or no treatment for prevention of UTI in females over the age of 18 years undergoing UDS.

Methods

The conduct and reporting of this review adhere to the principles outlined by the Centre of Reviews and Dissemination as well as the PRISMA guidelines [10,11,12] and is registered in PROSPERO-international prospective register of systematic reviews (ID#: CRD42020158347).

Eligibility criteria

Studies

As the prior 2012 Cochrane systematic review on this topic included studies published up to and including 2009, for this current review, randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials published from January 2009 to June 2019 were included. No language restrictions were applied.

Participants

Females 18 years of age or older who underwent UDS.

Interventions

Planned intervention of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Comparison

Planned comparator of placebo, no intervention or any other intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of UTI in the intervention and comparator groups, as defined by each study.

Search strategy

After several scoping searches, the keywords of relevant records and all NIH MeSH terms were reviewed by two study investigators. The full search strategy was then developed in conjunction with the research librarian associated with the study, and the systematic search was performed in MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global and COCHRANE on June 20, 2019. A sample search strategy for MEDLINE is shown in the Appendix Table 3. Any results from the electronic search that were proceedings of entire conferences were kept separately and hand searched. As well, reference lists of included studies, relevant systematic reviews and clinical trial registries were reviewed. Corresponding authors of included papers were contacted by email for information regarding studies in progress and unpublished research. Finally, searches were repeated November 7, 2019, and May 5, 2020, to identify any relevant new publications.

Screening and selection

Using Covidence™ systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), two study investigators independently screened all unique titles and abstracts and then resolved any discrepancies via consensus. Full-text articles were obtained for all abstracts included. The same two investigators then assessed the relevance of each full-text article independently, according to eligibility criteria. Authors were contacted by email for female-specific data if their studies presented both male and female data but otherwise met the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus or in conjunction with a third study investigator as required.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A standardized data extraction tool was first piloted and modified and then applied by two independent study investigators. Categories of data collected included study characteristics, design, methods including inclusion and exclusion criteria and UTI definition and identification, participant demographics, interventions, outcomes and adverse events. The trials were critically appraised using the modified Cochrane Collaboration tool to assess risk of bias of randomized controlled trials [13]. The modified Cochrane Collaboration tool was also used to report on funding bias while maintaining prior established validity. Any discrepancies were resolved in discussion with a third study investigator.

Methods of synthesis and analysis

Statistical analysis was performed according to Cochrane Collaboration guidelines in R-studio (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA). Data from intention-to-treat analysis were used where available. Results were given as odds ratios with 95% confidence interval and reported in forest plots. The primary outcome was symptomatic UTI following UDS in female patients treated with antibiotic prophylaxis compared with placebo or no treatment. Secondary outcomes included asymptomatic bacteriuria and adverse events in the same population studied.

Meta-analysis was not performed as the assumption of homogeneity was not met. Key clinical heterogeneity was noted in the intervention, i.e., the choice of antibiotic, its dosing and timing as well as outcome (i.e., UTI definition) (Appendix Table 4). The statistical heterogeneity between trials was also assessed by forest plot analysis. Subgroup analysis and publication bias/selective reporting analysis were not performed given the limited number of included studies.

Other quantitative descriptive data collected were summarized in fractions and ranges. Patient characteristics depicted by means and standard deviations in their studies of origin were assumed to be normally distributed and presented as median and intraquartile ranges for better comparison between studies. Student’s t-tests were also applied to normal characteristic data comparing the intervention and comparator groups where appropriate and not previously published.

Results

Description of studies

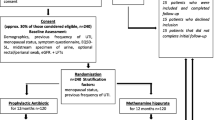

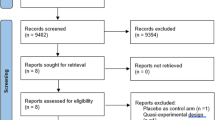

A total of 2811 records were screened for this review. The flow of literature through the search and appraisal process is shown in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). Five randomized controlled trials comparing the effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis in female patients were identified as relevant. Two trials were excluded from the review, one because the author did not respond to the request for female-specific data and the other because the author replied to the request for female-specific data, but data provided were incongruent with published results. Three randomized controlled trials involving 325 patients in total were included in this review [14,15,16]. An overview of these studies can be found in Table 1. Demographic characteristics and patient exclusion criteria by study are given in Table 2. Detailed characteristics of included and excluded studies can be found in Appendices Table 4 and 5.

Risk of bias and effects of intervention in included studies

One study was appraised to have an overall low risk for bias, while the other two were identified as high risk for bias in at least three domains evaluated (Figs. 2 and 3). The cumulative odds of women developing a UTI after UDS was higher in those that did not receive antibiotic prophylaxis than in those that did. However, analysis of individual study results through a forest plot demonstrated no significant trend (Fig. 4i). The cumulative odds of women developing bacteriuria after UDS were also higher in those that did not receive antibiotics prophylaxis than in those that did. In this scenario, analysis of individual study results in a forest plot demonstrated a trend towards a protective effect of antibiotic prophylaxis against bacteriuria following UDS (Fig. 4ii and iii). All three studies intended to report on adverse events but no adverse events were reported in any participant.

Discussion

As in the prior 2012 Cochrane review on this subject, our review of three randomized controlled trials did indicate that prophylactic antibiotics may reduce the risk of bacteriuria after UDS; however, there is not enough evidence to suggest this same intervention reduces the risk of UTI after UDS [7]. The study critically appraised as least likely biased showed a statistically significant effect of antibiotic prophylaxis in reducing bacteriuria following UDS [14], but it was not powered to show a significant change in incidence of UTI after UDS and thus it did not demonstrate an effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on UTI incidence after UDS in female patients [14]. The other two reviewed studies showed neither an effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on bacteriuria or UTI incidence in women undergoing UDS [15, 16].

The range of incidences of UTI post UDS in the reviewed studies (0.5%, 2.8% and 5.6%) was only comparable to the lower end of the spectrum of the published incidence rates of 4.3% to 19% [2, 4, 5]. Additionally, the rate of bacteriuria in the reviewed studies (2.8%, 4.1%, and 5.6%) was notably low when compared to published incidence rates of 7.9% to 11.6% [4, 17]. This female-specific systematic review therefore supports the SOGC guideline in not recommending antibiotic prophylaxis based on its chosen decision rule [3, 8].

Of the randomized control studies included, only one was found to have a low risk of bias [14]. The other two studies may have been influenced by a possible conflict of interest as well as performance bias and attrition bias [15, 16]. This, in combination with the above noted low incidence of outcomes in these small sample-size studies, means the present review demonstrates a continued need for further research and that the current ACOG guideline recommendation to not use antibiotics based on a lack of evidence is appropriate [6, 7, 18].

Our study boasts a robust search strategy created in collaboration with a research librarian. This review was primarily limited by the lack of good quality evidence and this is the cause of our inability to further define the efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis for UDS. Like our predecessors, our results must be interpreted with caution. The standard Cochrane risk-bias tool defined study biases and publication bias aside, further specific caveats to this review include the high degree of heterogeneity in antibiotic dose, duration and timing, timing of pre- and post-urodynamic urine culture and the heterogeneity in reporting of symptoms in women with bacteriuria after UDS. Furthermore, the definition of a UTI, transient bacteremia or asymptomatic bacteriuria in this patient population is very difficult. Thus, the definition alone of incidence in this population may be controversial, this even before considering self-reporting bias, validity and reliability.

The results of this review mean we must advocate for more research in this area, particularly female-specific research, such that practitioners performing UDS can make an informed decision with regard to the benefits of antibiotic prophylaxis versus the possible negative effects including increased antibiotic resistance and decreased microbiome diversity [9, 19, 20]. Of course, other considerations to decrease the risk of infection associated with catheterization are already being explored in the form of protein, silver and nitrazine coating of catheters, surface micropatterns on catheters and variable pre-procedural meatal cleaning [21,22,23,24,25,26]. In addition, alternative UTI prophylaxis with cranberry juice, cranberry extract, N-acetylcysteine and lactobacilli is also an emerging field of research to consider in this ongoing debate [15, 16, 27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

Conclusion

This systematic review of the literature demonstrates that antibiotic prophylaxis may significantly decrease bacteriuria in women following UDS; however, studies included in this review were not powered effectively to address the effect of antibiotic prophylaxis on UTI incidence in women after UDS. Further research is required to assess statistical and clinical efficacy of antibiotic prophylaxis against UTI after UDS in female patients.

References

Bradley CS, Smith KE, Kreder KJ. Urodynamic evaluation of the bladder and pelvic floor. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37(3):539–52, vii. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.006.

Yip SK, Fung K, Pang MW, Leung P, Chan D, Sahota D. A study of female urinary tract infection caused by urodynamic investigation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(5):1234–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.028.

Lowder JL, Burrows LJ, Howden NL, Weber AM. Prophylactic antibiotics after urodynamics in women: a decision analysis. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(2):159–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-006-0121-y.

Nobrega MM, Auge AP, de Toledo LG, da Silva Carramao S, Frade AB, Salles MJ. Bacteriuria and urinary tract infection after female urodynamic studies: risk factors and microbiological analysis. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(10):1035–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2015.05.031.

Tsai SW, Kung FT, Chuang FC, Ou YC, Wu CJ, Huang KH. Evaluation of the relationship between urodynamic examination and urinary tract infection based on urinalysis results. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;52(4):493–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tjog.2013.10.007.

ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 195: Prevention of infection after gynecologic procedures (2018). Obstet Gynecol 131 (6):e172-e189. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002670.

Foon R, Toozs-Hobson P, Latthe P. Prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the risk of urinary tract infections after urodynamic studies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD008224. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008224.pub2.

Van Eyk N, van Schalkwyk J. No. 275-antibiotic prophylaxis in Gynaecologic procedures. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2018;40(10):e723–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2018.07.007.

Pollack LA, Srinivasan A. Core elements of hospital antibiotic stewardship programs from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(Suppl 3):S97–100. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciu542.

Akers J, University of Y, Centre for R, Dissemination. Systematic reviews: CRD's guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: CRD, University of York; 2009.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005.

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928.

Hirakauva EY, Bianchi-Ferraro A, Zucchi EVM, Kajikawa MM, Girao M, Sartori MGF, et al. Incidence of bacteriuria after urodynamic study with or without antibiotic prophylaxis in women with urinary incontinence. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2017;39(10):534–40. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1604066.

Palleschi G, Carbone A, Zanello PP, Mele R, Leto A, Fuschi A, et al. Prospective study to compare antibiosis versus the association of N-acetylcysteine, D-mannose and Morinda citrifolia fruit extract in preventing urinary tract infections in patients submitted to urodynamic investigation. Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2017;89(1):45–50. https://doi.org/10.4081/aiua.2017.1.45.

Miotla P, Wawrysiuk S, Naber K, Markut-Miotla E, Skorupski P, Skorupska K, et al. Should we always use antibiotics after urodynamic studies in high-risk patients? Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1607425. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/1607425.

Bombieri L, Dance DA, Rienhardt GW, Waterfield A, Freeman RM. Urinary tract infection after urodynamic studies in women: incidence and natural history. BJU Int. 1999;83(4):392–5. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00924.x.

Grabe M, Botto H, Cek M, Tenke P, Wagenlehner FM, Naber KG, et al. Preoperative assessment of the patient and risk factors for infectious complications and tentative classification of surgical field contamination of urological procedures. World J Urol. 2012;30(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00345-011-0722-z.

Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol. 2008;6(11):e280. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280.

Tempera G, Furneri PM, Cianci A, Incognito T, Marano MR, Drago F. The impact of prulifloxacin on vaginal lactobacillus microflora: an in vivo study. J Chemother. 2009;21(6):646–50. https://doi.org/10.1179/joc.2009.21.6.646.

Arthanareeswaran VKA, Magyar A, Soos L, Koves B, Chandra AR, Justh N, et al. Evaluation of surface micropattern (sharklet) on Foleys silicon catheter in reducing urinary tract infections. J Urol. 2017;197(4):e270.

Fasugba O, Cheng AC, Gregory V, Graves N, Koerner J, Collignon P, et al. Chlorhexidine for meatal cleaning in reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: a multicentre stepped-wedge randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(6):611–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099%2818%2930736-9.

Leone M. Prevention of CAUTI: simple is beautiful. Lancet. 2012;380(9857):1891–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(12)61515-3.

Mitchell BG, Fasugba O, Gardner A, Koerner J, Collignon P, Cheng AC, Graves N, Morey P, Gregory V (2017) Reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections in hospitals: Study protocol for a multi-site randomised controlled study. BMJ Open 7 (11) (no pagination) (018871). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018871.

Pickard R, Lam T, Maclennan G, Starr K, Kilonzo M, McPherson G, et al. Types of urethral catheter for reducing symptomatic urinary tract infections in hospitalised adults requiring short-term catheterisation: multicentre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation of antimicrobial- and antiseptic-impregnated urethral catheters (the CATHETER trial). Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(47):1–197. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta16470.

Zhao P, Chen O, Lin C, Lin C, Wen X. Infection prevention with natural protein-based coating on the surface of Foley catheters: a randomised controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;388(S7). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31934-1.

Cadkova I, Doudova L, Novackova M, Huvar I, Chmel R. Effect of cranberry extract capsules taken during the perioperative period upon the post-surgical urinary infection in gynecology. Ceska Gynekol. 2009;74(6):454–8.

Ciudin A, Sanchez J, Wahab A, Mando S, Alcaraz A. Adding cranberry extract to flexible cystoscopy profilaxis decreases urinary infection rates. Eur Urol Suppl. 2015;14(2):e262.

Gunnarsson AK, Gunningberg L, Larsson S, Jonsson KB. Cranberry juice concentrate does not significantly decrease the incidence of acquired bacteriuria in female hip fracture patients receiving urine catheter: a double-blind randomized trial. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:137–43. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S113597.

Ataei S, Hadjibabaie M, Moslehi A, Taghizadeh-Ghehi M, Ashouri A, Amini E, et al. A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial on N-acetylcysteine for the prevention of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Hematol Oncol. 2015;33(2):67–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/hon.2141.

Barnoiu OS, Sequeira-Garcia Del Moral J, Sanchez-Martinez N, Diaz-Molina P, Flores-Sirvent L, Baena-Gonzalez V. American cranberry (proanthocyanidin 120 mg): its value for the prevention of urinary tracts infections after ureteral catheter placement. Actas Urol Esp. 2015;39(2):112–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acuro.2014.07.003.

Beerepoot MAJ, Ter Riet G, Nys S, Van Der Wal WM, De Borgie CAJM, De Reijke TM, et al. Lactobacilli vs antibiotics to prevent urinary tract infections: a randomized, double-blind, noninferiority trial in postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(9):704–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.777.

Juthani-Mehta M, Van Ness P, Bianco L, Rink A, Rubeck S, Ginter S, et al. Cranberry capsules for reduction of bacteriuria plus pyuria in nursing home women: a randomized clinical trial. Open Forum Infectious Diseases Conference: ID Week. 2016;3(Supplement 1). https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofw172.1059.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Kellie Murphy, Vice Chair of Research in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Toronto, who kindly gave us advice on how to perform a systematic review and counseled us throughout the process. We would also like to thank Sheryl Hewko, Clinical Research Manager of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Mount Sinai Hospital as well as John Matelski at the Biostatistics Research Unit.

This manuscript has not been presented in any format at a conference of meeting congress, but was accepted as an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Canadian Society for Pelvic Medicine that was to be held in Toronto in April 2020 but did not occur due to COVID-19. This study has also been accepted as an oral presentation at the upcoming International Urogynecology Association annual meeting in September 2020 (The Hague, The Netherlands).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A Benseler: Project development, Data Collection, Manuscript writing.

B Anglim: Data Collection, Manuscript writing.

ZY Zhao: Data Collection, Manuscript writing.

C Walsh: Data Collection.

CD McDermott: Project development, Data Collection, Manuscript writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Benseler, A., Anglim, B., Zhao, Z.Y. et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for urodynamic testing in women: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J 32, 27–38 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04501-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-020-04501-3