Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Women have a lifetime risk of undergoing pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery of 11–19%. Traditional native tissue repairs are associated with reoperation rates of approximately 11% after 20 years. Surgery with mesh augmentation was introduced to improve anatomic outcomes. However, the use of synthetic meshes in urogynaecological procedures has been scrutinised by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and by the European Commission (SCENIHR). We aimed to review trends in pelvic organ prolapse (POP) surgery in England.

Methods

Data were collected from the national hospital episode statistics database. Procedure and interventions-4 character tables were used to quantify POP operations. Annual reports from 2005 to 2016 were considered.

Results

The total number of POP procedures increased from 2005, reaching a peak in 2014 (N = 29,228). With regard to vaginal prolapse, native tissue repairs represented more than 90% of the procedures, whereas surgical meshes were considered in a few selected cases. The number of sacrospinous ligament fixations (SSLFs) grew more than 3 times over the years, whereas sacrocolpopexy remained stable. To treat vault prolapse, transvaginal surgical meshes have been progressively abandoned. We also noted a steady increase in uterine-sparing, and obliterative procedures.

Conclusions

Following FDA and SCENIHR warnings, a positive trend for meshes has only been seen in uterine-sparing surgery. Native tissue repairs constitute the vast majority of POP operations. SSLFs have been increasingly performed to achieve apical support. Urogynaecologists’ training should take into account shifts in surgical practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pelvic prolapse (POP) is a common disorder in women, with a prevalence of 40–60% [1]. The lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for POP is 11–19% [2], with a reoperation rate of approximately 11% after 20 years [3]. Various approaches have been introduced throughout the years and interventions offered may depend on several factors including type and degree of POP, patients’ characteristics and surgical expertise. Recent systematic reviews conclude that we currently lack strong evidence to guide practice in the surgical management of POP in women [4, 5].

The urogynaecologists’ repertoire has been rapidly evolving. Alongside traditional pelvic floor repairs, a number of interventions are now available to meet patients’ expectations. These include apical, uterine-sparing, and, possibly, obliterative procedures. Of note, the role of concomitant hysterectomy is largely debated and consensus has not yet been achieved [6].

In the last decade, synthetic meshes and biological grafts were developed with the aim of improving surgical outcomes. However, their use has become increasingly controversial. Following an escalation of mesh-related complications, warnings have been released by the US Food and Drug administration (FDA) in 2008 and 2011. In 2015, the Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) recommended that any vaginal mesh should only be considered in complex cases following POP recurrence. A significant reduction in the use of vaginal meshes for both primary and recurrent prolapse in the UK has been reported by the British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) members in a recent survey [7].

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) is a public domain database. It contains mandatory data from all surgical interventions performed in National Health Service (NHS) hospitals in England. Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Surgical Operations and Procedures, Fourth Edition (OPCS-4) is used as a coding system. Although the database has been developed for commissioning and reimbursement, current levels of reported accuracy support its use for research [8]. Although analyses of public domain HES data regarding procedures for stress urinary incontinence have recently been published [9, 10], studies using HES data for POP surgery have not been performed. A report from NHS digital recently summarised trends for urogynaecological procedures using HES data, but no conclusions were drawn [11] .

We aimed to investigate changes in surgical practice for POP at NHS hospitals in England over the last decade.

Materials and methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of HES data from the Health and Social Care Information Centre website. Four-digit procedure code tables were retrieved to quantify POP operations. Interventions considered and respective codes are listed in Table 1. We included annual reports from 2005 to 2016. The same codes were used for each year of the study period. Ethics approval was not required as we used public domain and anonymous data.

Results

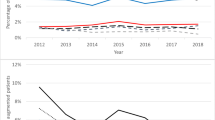

Overall, 299,618 admissions were considered in our analysis. Total numbers of POP procedures rose from 2005 to 2006 (n = 23,117), reaching a peak in 2013–2014 (n = 29,228). In the last 2 years, this trend reversed, with a reduction of 13% and 25,261 cases in 2015–2016 (Fig. 1). The vast majority of the procedures performed were native tissue repairs of the anterior and posterior compartments. In total, their numbers initially increased, reaching 25,445 in 2009–2010 and only recently dropped to 22,126 in 2015–2016. Within surgery for anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse, admissions for colporrhaphy with mesh augmentation increased only initially after the introduction of their OPCS-4 code in 2007–2008, when 1,145 procedures (4.5%) were carried out, to peak at 1,462 (5.6%) in 2008–2009, followed by a constant decrease with a nadir of 342 (1.5%) in 2015–2016. Specifically, vaginal meshes have been mainly introduced to augment the anterior vaginal wall, with coding raising from 704 (2007–2008) to 908 (2008–2009), then dropping to 231 (2015–2016; Fig. 2).

With regard to vault prolapse, sacrocolpopexy (SCP) has been consistently the most commonly performed procedure, ranging from 705 to 962 cases in 2006–2007 and 2014–2015 respectively. However, although admissions for SCP remained stable overall, the number of sacrospinous ligament fixations (SSLFs) grew more than 3 times over the years, with a peak of 747 cases in 2014–2015. Following an initial rise, transvaginal surgical meshes showed a substantial fall, from 210 in 2009–2010, to 45 in 2015–2016 (Fig. 3). Of note, the OPCS-4 code for SSLF and vaginal mesh augmentation were both introduced in 2006–2007.

We also noted a steep increase in uterine-sparing procedures, with a peak of 642 in 2014–2015 (Fig. 4). Trends for different interventions are shown in Fig. 5. Admissions for the suspension of the uterus using mesh have been coded since 2006–2007, whereas OPCS-4 codes for sacrohysteropexy and infracoccygeal hysteropexy were both introduced in 2011–2012. Sacrohysteropexy was the most commonly performed uterine-sparing procedure, with a twofold increase in numbers (from 168 to 368 between 2011 and 2012 and 2015–2016).

Obliterative procedures have been steadily rising up to 217 cases per year in 2015–2016 (Fig. 6). Of these, the almost all are represented by complete colpocleisis, whose numbers have been consistently higher than those for partial colpocleisis throughout the study period (Fig. 7).

Discussion

POP surgery constitutes a substantial workload for NHS hospitals. We analysed a large amount of mandatory data to highlight changes in surgical practice over the last decade. Admissions for native tissue repair represented the vast majority of POP operations. Meshes were mainly considered for uterine-sparing surgery, whereas vaginal mesh augmentation has been progressively abandoned. Procedures for apical support have become increasingly popular, with a rise in SSLFs. A positive trend was also noted for obliterative procedures, which can be a valuable option in selected cases.

The FDA safety communications regarding the use of meshes have drawn the attention of clinicians and media to the management options of POP. Subsequent changes in surgical practice have been reported in Europe and the USA. A 12-year analysis of the Portuguese National Medical Registry (2000–2012) showed a steep increase in vaginal mesh surgery between 2007 and 2011, with augmentation of the anterior vaginal wall representing 48% of all surgical mesh procedures. In 2012, however, although the use of vaginal mesh for apical defects almost doubled, the numbers for the anterior/posterior compartment showed a slight decrease [12]. A Finnish population-based register study over 23 years (1987–2009) revealed that colporraphies have been the most frequently used procedures for POP since 1991, whereas the use of vaginal meshes grew only slightly between 2006 and 2009 [13]. In the USA an obvious decline in mesh implant surgery has been described following FDA notifications. A report from a large regional hospital showed a drop in vaginal mesh procedures, which comprised 27 and 2% of prolapse repairs, in 2008 and 2011 respectively [14]. A recent study including 8 academic institutions across the USA, showed a gradual drop of mesh insertions between 2007 (n = 329) and 2011 (n = 236), followed by a sharp reduction in 2012 (n = 128) and 2013 (n = 71) [15]. Our data show similarities with the reports from USA. In England, vaginal repairs with mesh augmentation have remained overall low over the years. However, a gradual decrease started in 2009, probably as a result of the first FDA warning regarding mesh-related complications. Following the second FDA notification in 2011, the drop became more apparent. Unsurprisingly, in the last year, we found the nadir in the use of mesh for anterior/posterior compartment prolapse, with 342 admissions. This trend could be the result of both the patient’s and the surgeon’s preferences. The former may be less keen to undergo mesh augmentation surgery [16], whereas the latter may be prepared to offer meshes in only a small percentage of cases [7].

In our large cohort of almost 300,000 cases, the vast majority of admissions were represented by prolapse of the anterior/posterior compartment. Apical procedures were performed in approximately 5% of the cases. Of note, the database does not include a specific code for vaginal hysterectomy (VH) in the presence of prolapse. As a consequence, the total volume of procedures registered per year mainly depends on the performance of colporraphies. Overall, from 2005 to 2010, we demonstrated a noticeable rise, followed by a plateau until 2014, and a subsequent negative trend in the last 2 years. Potentially, FDA and SCENIHR warnings, alongside the negative publicity about meshes, may also have contributed to widely discouraging prolapse surgery.

We demonstrated a significant shift in the surgical approach of vault prolapse. Overall, numbers of procedures for vault suspension have been increasing over the last decade. This reflects the importance of level 1 and its role in supporting the upper part of the vagina. In fact, DeLancey’s anatomical studies have changed our understanding of pelvic floor anatomy and dynamics, and surgeons seem to be progressively more aware of his theory [17]. Despite being the gold standard for the surgical correction of vault prolapse, SCP has not gained popularity over the years. In fact, SCP results in prolonged operative time and recovery [18]. Warnings regarding transvaginal surgical meshes may also have had an impact on the use of abdominal meshes and discouraged patients from undergoing any type of mesh surgery for POP. On the other hand, SSLFs have been increasingly offered and nowadays represent a valuable option for apical support. With the introduction of suture devices, SSLFs have become safer and easier [19]. This may have led to a greater number of surgeons to lower the threshold for performing SSLFs, particularly when a concomitant colporrhaphy is carried out. Of note, after an initial rise, the use of transvaginal meshes for vault prolapse has been progressively abandoned, with less than 100 admissions per year in the last 3 years.

We also found an increase in uterine-sparing and obliterative procedures. Nowadays, more women of childbearing age seek care for POP [20]. Thus, surgical intervention is more likely to be offered at a younger age. Moreover, the proportion of women who prefer to preserve their uterus is rising, particularly between those with a higher education level [21]. In this scenario, meshes have been playing a pivotal role to allow uterine suspension despite a lack of clear evidence with regard to outcomes of uterine-preserving surgery versus hysterectomy [22]. Interestingly, surgeons have become gradually keener on offering obliterative procedures, such as colpocleisis. Considering England’s ageing population, this may represent a valuable option for frail patients with significant comorbidities who do not wish to maintain sexual function.

We identified several limitations to our study. First, the accuracy of our data depends on clinical coders. In particular, some codes were introduced only few years after the start of our analysis. Also, there is only a single code for VH, regardless of the clinical indication (POP versus menorrhagia). Moen and Richter documented a progressive reduction in the numbers of VH for menorrhagia, with a concomitant increase in the laparoscopic approach [23]. Thus, we were unable to estimate the proportion of VH performed for POP, as this is likely to change throughout the study period. We therefore excluded these admissions from our study to avoid inaccurate conclusions. Moreover, we could not comment on different mesh types/materials, mesh-related complications (e.g., excision of vaginal mesh) and surgical approaches (e.g., laparotomy versus laparoscopic versus robotic procedures) as these are not coded in the database. On the other hand, we identified overlapping codes (e.g., suspension of the uterus using mesh versus sacrohysteropexy). Also, we could only use public domain data, although we did not have access to patient-level data, and no further pattern could be highlighted. Finally, data from the private sector were not available.

The HES database represents an important tool for following shifts in prolapse surgery, as these data possibly influence different aspects of our subspecialty. For instance, our results can help managers to tailor financial resources and workforce planning. Urogynaecologists’ training programmes should also look into current trends and develop accordingly. Furthermore, future versions of the database could potentially address differences between types of mesh and surgical techniques. These changes may potentially help clinicians to improve patients’ care and meet their expectations.

References

Handa VL, Garrett E, Hendrix S, Gold E, Robbins J. Progression and remission of pelvic organ prolapse: a longitudinal study of menopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190(1):27–32.

Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(5):1096–100.

Lowenstein E, Moller LA, Laigaard J, Gimbel H. Reoperation for pelvic organ prolapse: a Danish cohort study with 15–20 years' follow-up. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(1):119–24.

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD004014.

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Christmann-Schmid C, Haya N, Brown J. Surgery for women with anterior compartment prolapse. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD004014.

Gutman RE. Does the uterus need to be removed to correct uterovaginal prolapse? Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2016;28(5):435–40.

Jha S, Cutner A, Moran P. The UK National Prolapse Survey: 10 years on. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;29(6):795–801.

Burns EM, Rigby E, Mamidanna R, Bottle A, Aylin P, Ziprin P, et al. Systematic review of discharge coding accuracy. J Public Health (Oxf). 2012;34(1):138–48.

Withington J, Hirji S, Sahai A. The changing face of urinary continence surgery in England: a perspective from the hospital episode statistics database. BJU Int. 2014;114(2):268–77.

Gibson W, Wagg A. Are older women more likely to receive surgical treatment for stress urinary incontinence since the introduction of the mid-urethral sling? An examination of hospital episode statistics data. BJOG. 2016;123(8):1386–92.

NHS Digital. Retrospective Review of Surgery for Urogynaecological Prolapse and Stress Urinary Incontinence using Tape or Mesh 2018 [Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mesh/apr08-mar17/retrospective-review-of-surgery-for-vaginal-prolapse-and-stress-urinary-incontinence-using-tape-or-mesh-copy#key-facts.

Mascarenhas T, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M Jr, Ricon-Ferraz A, Nogueira P, Lopes F, Freitas A. Pelvic organ prolapse surgical management in Portugal and FDA safety communication have an impact on vaginal mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26(1):113–22.

Kurkijarvi K, Aaltonen R, Gissler M, Makinen J. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in Finland from 1987 to 2009: a national register based study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;214:71–7.

Skoczylas LC, Turner LC, Wang L, Winger DG, Shepherd JP. Changes in prolapse surgery trends relative to FDA notifications regarding vaginal mesh. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(4):471–7.

Younger A, Rac G, Clemens JQ, Kobashi K, Khan A, Nitti V, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in academic female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery urology practice in the setting of the food and drug administration public health notifications. Urology. 2016;91:46–51.

Notten KJ, Essers BA, Weemhoff M, Rutten AG, Donners JJ, van Gestel I, et al. Do patients prefer mesh or anterior colporrhaphy for primary correction of anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a labelled discrete choice experiment. BJOG. 2015;122(6):873–80.

DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 Pt 1):1717–24. discussion 24–8

Paz-Levy D, Yohay D, Neymeyer J, Hizkiyahu R, Weintraub AY. Native tissue repair for central compartment prolapse: a narrative review. Int Urogynecol J. 2017;28(2):181–9.

Mowat A, Wong V, Goh J, Krause H, Pelecanos A, Higgs P. A descriptive study on the efficacy and complications of the Capio (Boston Scientific) suturing device for sacrospinous ligament fixation. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;58(1):119–24.

Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1278–83.

Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, Richardson ML, Book NM, Yip S, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470.e1–6.

Detollenaere RJ, den Boon J, Stekelenburg J, IntHout J, Vierhout ME, Kluivers KB, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with suspension of the uterosacral ligaments in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: multicentre randomised non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2015;351:h3717.

Moen MD, Richter HE. Vaginal hysterectomy: past, present, and future. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(9):1161–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Martino Zacche does not have any conflict of interest. Sambit Mukhopadhyay accepted travel expenses from Dynamesh, Astellas, Kebomed UK, Cook Medical. Ilias Giarenis received speaker honoraria from Astellas.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zacche, M.M., Mukhopadhyay, S. & Giarenis, I. Trends in prolapse surgery in England. Int Urogynecol J 29, 1689–1695 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3731-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-018-3731-2