Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

Uterine prolapse is a common health problem and the number of surgical procedures is increasing. No consensus regarding the surgical strategy for repair of uterine prolapse exists. Vaginal hysterectomy (VH) is the preferred surgical procedure worldwide, but uterus-preserving alternatives including the Manchester procedure (MP) are available. The objective was to evaluate if VH and the MP are equally efficient treatments for uterine prolapse with regard to anatomical and symptomatic outcome, quality of life score, functional outcome, re-operation and conservative re-intervention rate, complications and operative outcomes.

Methods

We systematically searched Embase, PubMed, the Cochrane databases, Clinicaltrials and Clinical trials register using the MeSh terms “uterine prolapse”, “uterus prolapse”, “vaginal prolapse” “pelvic organ prolapse”, “prolapsed uterus”, “Manchester procedure” and “vaginal hysterectomy”. No limitations regarding language, study design or methodology were applied. In total, nine studies published from 1966 to 2014 comparing the MP to VH were included.

Results

The anatomical recurrence rate for the middle compartment was 4–7 % after VH, whereas recurrence was very rare after the MP. The re-operation rate because of symptomatic recurrence was higher after VH (9–13.1 %) compared with MP (3.3–9.5 %) and more patients needed conservative re-intervention (14–15 %) than after MP (10–11 %). After VH, postoperative bleeding and blood loss tended to be greater, bladder lesions and infections more frequent and the operating time longer.

Conclusions

This review is in favour of the MP, which seems to be an efficient and safe treatment for uterine prolapse. We suggest that the MP might be considered a durable alternative to VH in uterine prolapse repair.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The prevalence of anatomical uterine prolapse is 14.2 % in postmenopausal women in a large population-based study [1]. The lifetime risk of undergoing at least one operation for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence is 11–20 % [2, 3], and, owing to the aging population in most western countries, the number of operations performed has been increasing over the last decade [4]. In the USA around 350,000 prolapse surgeries are performed annually, of which around 50 % include repair of prolapse in the middle compartment [5].

Despite great activity, no consensus regarding the surgical strategy for repair of uterine prolapse exists internationally, and the topic remains controversial. The surgical procedures vary greatly worldwide. However, vaginal hysterectomy (VH) tends to be the preferred surgical procedure for uterine prolapse repair in the world today [6, 7]. The Manchester procedure (MP) is a uterus-preserving method that has proven durable and safe [8], and may be considered a reasonable alternative to hysterectomy as a treatment of uterine prolapse. Most MPs performed today are modified versions of the original MP first performed in 1888. The original MP consisted of an amputation of the cervix combined with an anterior and posterior colporrhaphy. Later, the technique was modified by de-attachment of the cardinal ligaments, which, after cervix amputation, are sutured to the corpus–cervical zone to keep the uterus elevated. An anterior colporrhaphy is routinely performed and, when indicated, a posterior colporrhaphy too. In cases of pronounced cervical elongation, cervix amputation can be undertaken as an isolated procedure without concomitant colporrhaphy.

The objective of this review is to compare VH with the MP in the treatment of uterine prolapse regarding postoperative outcome, risk of complications, durability, recurrence of symptoms and need for re-surgery.

Materials and methods

We carried out a systematic review based on the following clinical questionnaire:

-

1.

Population: women with uterine prolapse requiring surgical treatment

-

2.

Intervention: surgical repair of uterine prolapse by either VH or the MP

-

3.

Comparison: surgical repair by VH compared with repair using the MP

-

4.

Outcomes: anatomical and symptomatic outcome in the same or another compartment, quality of life score, functional outcome, re-operation and conservative re-intervention rate, complications and operative outcomes

Search strategy

An extensive systematic search was carried out in PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane databases using the terms “uterine prolapse”, “uterus prolapse”, “vaginal prolapse”, “pelvic organ prolapse”, “prolapsed uterus”, “Manchester operation/repair/procedure/method”, “Manchester–Fothergill”, “uterine prolapse and Manchester operation”, “uterine prolapse and vaginal hysterectomy”, and “Manchester operation and vaginal hysterectomy”. The systematic search was assisted by a professional scientific librarian.

Further manual searches of the reference lists in relevant articles, books and reviews were carried out. No ongoing clinical trials comparing VH with the MP as a treatment of uterine prolapse were identified through the clinical registers, www.clinicaltrials.gov and www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu.

No limitations regarding language, study design, methodology, sample size number, follow-up or year of publication were applied. All non-English publications were translated and screened as described. Our search strategy was adapted to suit each database. The last search was undertaken on 10 June 2016.

Study selection

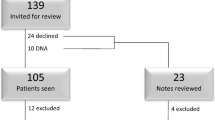

All the studies identified underwent abstract screening and those eligible were full-text screened. Studies were selected for the review if they met the eligibility criteria of comparing VH with the MP as a treatment for uterine prolapse. Studies were also considered eligible if they provided a comparison of more surgical procedures for the treatment of uterine prolapse, but only if VH and the MP were included, and if data for each procedure were available for individual analysis (Fig. 1).

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the studies included according to availability. Not all of the selected outcomes were examined or described in all the papers included. We extracted data on method, patient characteristics and outcomes (Table 1).

Results

The Embase search identified 37 publications, and the search in PubMed resulted in 10 publications, all of them duplicates from the Embase search. Another duplicate publication was identified through a search in the Cochrane databases. Four of the identified studies were not in the English language, 1 of which was in Russian, 1 in Dutch, 1 in German and 1 in Danish.

Through other sources, an additional 28 records were found, leading to a total of 65 records for screening. After screening by abstract, 22 records were excluded. Full-text screening of 43 records was carried out, and 34 of these were excluded for the reasons listed in Fig. 1. Two studies were excluded because of a systematic difference between the VH and the MP groups, as patients in the VH group were consistently older than patients in the MP group. The records comparing more surgical procedures for the treatment of uterus prolapse, including VH and the MP, were excluded in case the data were pooled and not available for each procedure for individual analysis. Nine studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review (Table 1).

Of the studies included only 1 study was a randomised controlled trial, whereas 6 were retrospective cohort studies, 3 of which were matched. One study was a database register study and another was a prospective observational follow-up study. The randomised controlled trial included has some limitations, as the sample size is small and only total vaginal length (TVL) and the POP-Q C-point were measured.

The Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines were followed (Fig. 1).

The studies are highly heterogeneous in terms of study design, outcome measures, follow-up time and number of participating patients. Some only compared the VH with the MP and others compared a number of different surgical techniques with the VH and the MP being just two among more techniques. Some focused only on outcomes related directly to the surgical procedure, such as operating time, blood loss etc., whereas others had anatomical or symptomatic POP recurrence, need for re-intervention and patient satisfaction as their main outcomes. Regarding the MP, a number of variations of this procedure were performed, most of them modified from the original MP. In some of the studies, not all patients underwent an anterior colporrhaphy. In general, the performance of a posterior colporrhaphy varies as it is performed only on indication in some and consistently as a prophylactic procedure in others. Information on the MP method is missing in 3 studies, whereas an unmodified version of the MP was only performed in 2. Information on the exact VH method is lacking in 3 studies, but in general the vaginal vault was fixated to the uterosacral ligaments. In some studies, the VH was combined with either an anterior or a posterior colporrhaphy if indicated, and in others the VH was consistently combined with a prophylactic posterior colporrhaphy or a combined prophylactic anterior and posterior colporrhaphy.

Outcome measures

Anatomical outcome

A randomised controlled trial found a significantly shorter vaginal length after VH compared with MP (6.0 cm vs 8.3 cm, p = 0.02) [9], whereas a non-significant difference in the POP-Q point C was found (−6.0 vs −6.3, p = 0.1).

Surgical failure was defined as a POP-Q stage ≥ 2 at 5 years’ follow-up by Miedel et al. [10]. The frequency of the anatomical recurrence of POP in any compartment was high, at 50 % after VH and 44.6 % after MP. The distribution of POP after VH was 73 % in the anterior compartment, 7 % vaginal vault prolapses and no isolated POP in the posterior compartment. In 20 %, POP was found in more than one compartment. After MP, the distribution showed 60 % in the anterior compartment, no isolated POP in the middle compartment, 15 % in the posterior compartment and 24 % in more than one compartment. The presence of anatomical recurrence was accompanied by symptoms in 33.3 % after VH and 57.6 % after MP.

In another study, recurrence was also defined as POP-Q stage 2 or more, independent of the compartment in which the prolapse appeared [11]. A high recurrence rate was observed for the anterior compartment, at 47.9 % in the VH group vs 46 % in the MP group. The recurrence rate in the middle compartment was 4 % in the VH group and no recurrence was seen in the MP group at the 1-year follow-up.

A third study found that 39 % of all recurrences were symptomatic, but that recurrence was not well-defined in this study [12].

Symptomatic outcome

Postoperative symptoms were assessed using the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) [13, 14] by two studies.

An improvement in all domains of the UDI was shown for both operations by De Boer [11] when the preoperative score was compared with the score 1 year postoperatively. For POP symptoms, the decrease in score after surgical treatment was 41.9 (80 %) after VH vs 43.1 (84.7 %) for the MP. The postoperative score was 10.5 after VH and 7.8 after MP. However, the difference between the groups was not significant.

After a median follow-up of 6 years, Thys et al. [15] compared the UDI after the two procedures (11.6 after VH vs 11.0 after the MP), and in accordance with De Boer, did not show any significant differences between the groups.

Quality of life

Quality of life was only assessed in 2 studies, 1 of which found a significant improvement in prolapse-related quality of life scores after surgery in both groups (from 40 to 16 after both VH and the MP), but there were no significant differences between the groups [9]. The other study only assessed the quality of life postoperatively and did not show a significant difference between the groups either [15].

Functional outcome

Two studies examined the changes in urinary incontinence in relation to VH and the MP and both found an improvement in urinary incontinence from preoperatively to postoperatively in both groups [11, 15]. One of the studies showed a decrease in urinary incontinence from 48 % in both groups to 13 % after VH and 20 % after MP [15], whereas the other found a decrease in the UDI incontinence score of 6.4 after VH and 12.6 after the MP [11]. However, none of these differences were significant. No information was available on the proportion of cured or de novo incontinence in any of the studies.

Two studies examined sexual function and found no difference after either of the two procedures [9, 15].

Re-operation rate and conservative re-intervention rate

As a measure of procedure efficacy three studies evaluated the need for re-intervention consisting of the re-operation rate and the need for conservative re-intervention.

At a mean follow-up of 53.2 months, one study found a re-operation rate of 13.3 % after VH vs 9.5 % after MP. Most of the symptomatic anatomical recurrences were prolapse in another compartment and as such the re-operation was a primary prolapse surgery at a different site. It is not possible to distinguish between this type of surgery and repeat surgery at the same site for each procedure as data are pooled [10].

In another study, POP recurrence was defined as any stage of POP that required re-intervention. The median follow-up in the VH group was 75 months and 68 months in the MP group. The conservative re-intervention rate was 14 % after VH and 11 % after the MP (p = 0.52) and the surgical re-intervention rate was 9 % after VH vs 4 % after the MP (p = 0.15). After VH, 77.8 % of the re-operations were primary prolapse surgeries at a different site (anterior or posterior colporrhaphies without mesh) and 22.2 % repeat surgeries at the same site (sacral colpopexy). For the MP, the numbers were 75 % primary prolapse surgeries at a different site (anterior or posterior colporrhaphies without mesh) and 25 % repeat surgery at the same site (Amreich–Richter). The time to re-surgery was significantly shorter (8 months) after VH (p = 0.03), and the hazard ratio for POP recurrence was 2.5 (confidence interval: 0.8–8.0) in favour of the MP [15].

Symptomatic recurrence requiring treatment occurred in 15 % after VH and 10 % after the MP (p = 0.28) at 1-year follow-up, and conservative re-intervention was needed in 15 % after VH vs 10 % after the MP (p = 0.28). Re-operation was performed in 9.1 % after VH and 3.3 % after the MP. All re-operations were primary prolapse surgeries at a different site, with 1 anterior colporrhaphy and 2 posterior colporrhaphies after VH and 1 posterior colporrhaphy after the MP. Notably, the number of patients in this study was very low. The hazard ratio for POP recurrence in this study was identical to the hazard ratio in Thys et al., 2.5 (confidence interval: 0.8–8) in favour of the MP [12].

Complications

Perioperative complications

Injuries to the bladder occurred in 1–3 % after VH vs 0–0.4 % after the MP, whereas bowel lesions were seen in 0–0.5 % after VH compared with 0.4–1 % after the MP [16, 17].

Postoperative complications

Postoperative haemorrhage

Four studies determined postoperative haemorrhage (e.g. manifested as a haematoma), which occurred in 1–6 % after VH vs 0–3 % after the MP [10, 12, 15, 16]. These findings are in accordance with those of another study that found a significantly increased risk of further surgery after VH (6 % vs 3 %, p = 0.0002), because of postoperative bleeding, bladder injury and infection [17].

Infection

Oral antibiotic treatment for vaginal infection, abscess, urinary tract infection, renal infection or for unstated reasons was needed in 21.1 % in the VH group and 14.8 % in the MP group. A difference was seen for vaginal infection and abscess, as antibiotic treatment was given to 4.8 % after VH and none after the MP. However, this difference was not significant [18]. Another study explored postoperative urinary tract infection and showed a high rate of infections, with 30 % (10 patients) after VH vs 15 % (5 patients) after MP, with no significant difference between the groups [12].

Urinary retention

In one study the tendency towards delayed hospital discharge due to urinary retention was found to be lower after VH (8.6 % vs 17.1 %), but the difference was not significant [18]. In a recent study, urinary retention was seen in 19 % after VH compared with 25 % after the MP [12]. These numbers were slightly lower in another study, as 12 % in the VH group and 9 % in the MP group experienced urinary retention (p = 0.3) [11]. Notably, urinary retention was not defined in any of the studies.

Operative outcomes

Operating time

Five studies compared the operating time of VH with that of the MP and a significantly shorter operating time for the MP was found in all studies [9, 11, 12, 18, 19]. Some studies provided the mean operating time, whereas others provided the median time. The range for the mean/median operating time for the VH was 77.8 to 130 min vs 62.4 to 110 min for the MP. In general, the operating time was shorter for both procedures in the more recent studies.

Blood loss and blood transfusions

The mean perioperative blood loss was measured in five studies [11, 12, 16, 18, 19]. The range of the mean perioperative blood loss was 180–623 mL for VH vs 191–408 mL for the MP [14–16]. Four studies found greater blood loss for VH [11, 12, 16, 18], whereas one [19] found greater blood loss for the MP. In general, the blood loss for both procedures was lower in the more recent studies. Two studies appraised the need for blood transfusions after the surgical procedures, and more patients in the VH group (11 %) needed blood transfusions compared with the MP group (4 %) [18, 19].

Duration of hospital stay

Duration of the hospital stay was assessed by 7 studies [9, 11, 16–19]. In 6, the patients had a longer hospital stay after VH compared with the MP. Only 1 study found a significantly shorter hospital stay after VH (a mean of 5.2 days vs 6.1 days respectively; p = 0.018) [11]. In general, the duration of the hospital stay was considerably shorter in the more recent studies.

Discussion

The literature comparing the MP with VH for the treatment of uterine prolapse is limited, and nearly half of the studies included in this review are 20 years old or more. The large timespan between the studies makes comparison difficult, as the surgical settings and routines have changed considerably over the years. In general, the studies are heterogeneous, which also contributes to difficulties with comparisons.

During our search, we identified two reviews on the surgical repair of uterine prolapse in which the MP and the VH were examined. One was published in 2009 [20] and none of the studies included compared VH with the MP. The other review from 2011 [21] was narrative and included studies both comparing and not comparing VH with the MP. All of the comparative studies from this review are included in the present review. Subsequently, three studies have been published including the only randomised controlled trial.

The studies focus on a number of different outcomes, and regarding durability, most studies focus on the anatomical outcome, symptomatic outcome and the surgical and conservative re-intervention rate.

Anatomical recurrence in any compartment was very frequent after both procedures, with a clear excess in the anterior compartment. This tendency towards recurrence in this compartment is well known, but is often asymptomatic [22]. An anatomical recurrence rate of 4–7 % for vaginal vault prolapse after VH was seen [10, 11], which is in accordance with the literature, as vaginal vault prolapse requires surgical repair in 6–8 % of all patients after VH [23]. Anatomical recurrences in the middle compartment were very rare after the MP. In one study, a shorter vaginal length after VH was seen, which can affect the functionality of the vagina.

Many studies did not examine postoperative symptoms, even though the absence of a vaginal bulge should be considered the most important measure of treatment success. In the two studies examining symptomatic outcome no difference in the postoperative UDI prolapse score was found between the two procedures.

It is known that POP surgery can aggravate urinary incontinence or cause de novo incontinence owing to existing masked incontinence. However, improvements can be obtained as well. The two studies that assessed changes in urinary incontinence found an improvement in both groups, with nether procedure being superior to the other in this matter.

Within 5 years’ follow-up significantly more patients had proceeded to re-operation after VH because of symptomatic recurrence. One study showed a significantly shorter time interval to re-intervention after VH [15]. This is in accordance with Oversand et al. [8], who showed excellent results of the MP when carried out in a dedicated urogynecological unit. In this study, 95 % of the patients reported subjective satisfaction at follow-up 1 year postoperatively, concomitant with 86.7 % having POP-Q stage 0–1. At follow-up after 5 years, the re-operation rate was 2.6 %.

The re-operation rate was higher after VH (9–13.1 %) compared with MP (3.3–9.5 %) [10, 12, 15 ]. As expected, the lowest rate (9.1 % for VH and 3.3 % after the MP) was seen in the study with the shortest follow-up (12 months) [12]. This trend was recovered regarding conservative re-intervention, where more patients needed conservative re-intervention after VH (14–15 %) than after the MP (10–11 %) [12, 15]. The conservative re-intervention rate did not seem to change substantially with the longer follow-up, as it was almost identical in the two studies, despite one having six times longer follow-up (68–75 months) [15] than the other (12 months) [12].

With reference to complications, there is a trend towards greater postoperative bleeding, more bladder lesions and more infections after VH compared with post-MP. In line with that, Ottesen et al. [17] showed a significantly increased risk of further surgery due to postoperative haemorrhage, bladder injury and infection after VH in a large register study.

Two studies examined urinary retention and no significant difference between the two procedures was seen. However, no definition of urinary retention was stated in any of the studies.

The results of this review underline that VH is a more invasive procedure than the MP. The need for re-surgery because of postoperative bleeding, bladder injury and infection is more frequent after VH than after the MP. In addition, the operating time tends to be longer, the blood loss larger and transfusions needed more frequently. None of the studies assessed any socioeconomic outcomes, but from an economic point of view the MP appears advantageous too. The MP is often undertaken as out-patient surgery, contrary to VH, which can be performed as such, but most often requires hospitalisation.

Critics of the MP may state that uterus-preserving surgical methods carry an inherent risk of future uterine pathological conditions. In some cases, cervical stenosis may develop after the MP, eventually leading to haematometra and an absence of symptoms of uterine pathological conditions. The risk of development of endometrial cancer after uterus-preserving POP surgery has been shown to be only 0.24 to 0.35 % [24, 25], which was confirmed in a recent study evaluating the utility of vaginal hysterectomy when colpocleisis is performed to avoid future cases of endometrial cancer [26]. In a decision analysis model, it was found that the expected utility for colpocleisis alone was higher than for colpocleisis combined with a vaginal hysterectomy for women aged 40–90 years. That said, VH is definitely eligible to be a treatment of uterine prolapse in cases of an identified uterine pathological condition before surgery.

The MP is the only uterine-sparing procedure that is compared with VH in this review. Some critics may proclaim that the MP is an old and outdated operation that has been replaced by more advanced uterine-preserving procedures, of which sacrospinous hysteropexy (SH) is one of the best studied techniques. In a randomised controlled trial [27] SH was compared with VH, and the time from surgery to return to work was significantly shorter after SH (43 vs 66 days, p = 0.02), but no differences in quality of life or functional outcomes were found between the two groups. In contrast to the shorter recovery time after SH, POP recurrence in the middle compartment (stage 2 or more) at the 1-year follow-up was notably more frequent after SH, with a 17 % higher risk after SH (21 % after SH vs 3 % after VH, p = 0.03). However, Lin [28] found that when SH was combined with a cervical amputation, as performed during the MP, no recurrence was seen.

A number of mesh-based operations for the repair of uterine prolapse are available, but should be strictly limited to selected cases of uterine prolapse, as the rate of mesh-related complications is up to 15–25 % after transvaginal mesh insertion for POP repair, with mesh erosions in up to 10 % of patients [29, 30]. In 2008, these findings led to the FDA public health notification on mesh use, with an update in 2011 [31, 32]. In accordance with that, a scientific committee (SCENIHR) under the European Commission in 2015 stated that the use of meshes for POP repair should usually be considered as a second choice after failed primary surgery [33]. In many countries, these notifications have caused a decrease in the use of mesh and many mesh kits have been withdrawn from the market. New types of mesh have been introduced, but so far little is known about their safety as long-term follow-up is lacking.

Another aspect when considering the choice of surgical method is the patients’ preference. Two studies from 2013 [34, 35] surveyed patient preference for uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in women with uterovaginal prolapse. One study [34] found that 60 % would prefer another surgical option to hysterectomy if the alternative option was equally as efficient. Hysterectomy was only preferable if its benefit substantially exceeded the benefit of an alternative uterine-preserving procedure. The other study [35] supports these findings, as 36 % preferred uterine-preserving surgery and only 20 % preferred hysterectomy when the outcomes of the procedures were considered equal. The preference for uterine-preserving surgery was so strong that 21 % of the patients persistently preferred it to VH, even if hysterectomy was proven to be superior. Sufficient evidence-based information for patients is required if they are to provide informed consent on the choice of surgery based not on beliefs or trust in the doctor’s personal opinion. Doctors’ current preference for VH in the treatment of uterus prolapse is striking as it does not sufficiently rely on evidence. In general, there is an ongoing trend in surgery leading to an increasing number of minimally invasive procedures in many fields, including gynaecology. In the light of this, the sustained preference for VH stimulates a great deal of thought. An explanation could be that in many clinics VH has been performed as a routine treatment of uterine prolapse for decades and hence experience with other surgical procedures, including the MP, is lacking.

This review is in favour of the MP, but the benefits cannot necessarily be transferred to other uterine-preserving methods, whether based on native tissue repair or not. Comparisons of uterine-preserving surgical methods in general are scarce, and studies on the MP vs other uterine-preserving methods are lacking, as uterine-preserving surgical methods in general are compared with VH, even though they represent two distinctly different surgical approaches.

We regard our broad inclusion criteria, according to which no studies were excluded because of language, method, sample size, follow-up or year of publication, as strengths of this review, although it also causes some limitations owing to the heterogeneity of the studies. Some studies included patients who had undergone previous surgery because of POP or UI [10, 11], and in one study concomitant surgery for UI was performed in some patients [10].

Conclusion

This review challenges the position of VH as the preferred surgical treatment of uterine prolapse. The durability of the MP appears to be superior, as prolapse recurrence is more frequent after VH and both the re-operation rate and the rate of conservative re-intervention due to symptomatic recurrence is higher after VH. In addition, there is a trend towards greater postoperative bleeding, more bladder lesions and more infections after VH. The operating time is longer, blood loss tends to be higher and transfusions are also needed more frequently. Based on the findings in this review, we suggest that the MP should be considered a durable alternative to VH for treatment of uterine prolapse, but randomised controlled trials and larger long-term prospective studies on this topic are required.

References

Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the women’s health initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(6):1160–6.

Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JCR, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501–6.

Wu JM, Matthews CA, Conover MM, Pate V, Jonsson FM. Lifetime risk of stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1201–6.

Elterman DS, Chughtai BI, Vertosick E, Maschino A, Eastham JA, Sandhu JS. Changes in pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the last decade among United States urologists. J Urol. 2014;191(4):1022–7.

Brown JS, Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden S, Vittinghoff E. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States, 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):712–6.

Vanspauwen R, Seman E, Dwyer P. Survey of current management of prolapse in Australia and New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(3):262–7.

Jha S, Moran P. The UK national prolapse survey: 5 years on. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(5):517–28.

Oversand SH, Staff AC, Spydslaug AE, Svenningsen R, Borstad E. Long-term follow-up after native tissue repair for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(1):81–9.

Ünlübilgin E, Sivaslioglu A, Ilhan T, Kumtepe Y, Dölen I. Which one is the appropriate approach for uterine prolapse: Manchester Procedure or vaginal hysterectomy? Turk Klin J Med Sci. 2013;33(2):321–5.

Miedel A, Tegerstedt G, Mörlin B, Hammarström M. A 5-year prospective follow-up study of vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(12):1593–601.

De Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, Withagen MIJ, Vierhout ME. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(11):1313–9.

Iliev VN. Uterus preserving vaginal surgery versus vaginal hysterectomy for correction of female pelvic organ prolapse. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2014;35(1):243–7.

Uebersax JS, Wyman JF, Shumaker SA, McClish DK, Fantl JA. Short forms to assess life quality and symptom distress for urinary incontinence in women: the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urogenital Distress Inventory. Continence Program for Women Research Group. Neurourol Urodyn. 1995;14(2):131–9.

van der Vaart CH, de Leeuw JRJ, Roovers J-PWR, Heintz APM. Measuring health-related quality of life in women with urogenital dysfunction: the urogenital distress inventory and incontinence impact questionnaire revisited. Neurourol Urodyn. 2003;22(2):97–104.

Thys SD, Coolen A-L, Martens IR, Oosterbaan HP, Roovers J-PWR, Mol B-W, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22(9):1171–8.

Rubin A. Complications of vaginal operations for pelvic floor relaxation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1966;95(7):972–4.

Ottesen M, Utzon J, Kehlet H, Ottesen BS. Vaginal surgery in Denmark in 1999–2001. An analysis of operations performed, hospitalization and morbidity. Ugeskr Laeger. 2004;166(41):3598–601.

Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, Bodian C, Friedman F, Bogursky E. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40(4):299–304.

Kalogirou D, Antoniou G, Karakitsos P, Kalogirou O. Comparison of surgical and postoperative complications of vaginal hysterectomy and Manchester procedure. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 1996;17(4):278–80.

Dietz V, Koops SES, van der Vaart CH. Vaginal surgery for uterine descent; which options do we have? A review of the literature. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;20(3):349–56.

Detollenaere RJ, den Boon J, Vierhout ME, van Eijndhoven HWF. Uterussparende chirurgie versus vaginale hysterectomie als behandeling van descensus uteri. Litteratuuronderzoek Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2011;155:A3623.

Shull BL, Bachofen C, Coates KW, Kuehl TJ. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183(6):1365–73, discussion 1373–1374.

Aigmueller T, Dungl A, Hinterholzer S, Geiss I, Riss P. An estimation of the frequency of surgery for posthysterectomy vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(3):299–302.

Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, Barber MD. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(5):507.e1–4.

Hanson GE, Keettel WC. The Neugebauer-Le Fort operation. A review of 288 colpocleises. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;34(3):352–7.

Jones KA. Hysterectomy at the time of colpocleisis: a decision analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2016;27(5):805–10.

Dietz V. One-year follow-up after sacrospinous hysteropexy and vaginal hysterectomy for uterine descent: a randomized study. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21(2):209–16.

Lin T-Y. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104(4):249–53.

Barski D, Otto T, Gerullis H. Systematic review and classification of complications after anterior, posterior, apical, and total vaginal mesh implantation for prolapse repair. Surg Technol Int. 2014;24:217–24.

Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Schmid C. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD004014.

FDA. FDA Public Health Notification: Serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh in repair of pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence. 2008.

FDA. FDA Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse: FDA Safety Communication. 2011.

Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks, SCENIHR. Opinion on the safety of surgical meshes used in urogynecological surgery. European Commission; 2015.

Frick AC. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19(2):103–9.

Korbly NB. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209(5):470–6.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge doctor Svetlana Rygaard Nielsen for translating the Russian study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

CK Tolstrup received travel expenses and conference fees for the EUGA Annual Congress Leading Lights 2015 from by Astellas Pharma; Gunnar Lose received research grants from Astellas Pharma and consultant fees from Contura; Niels Klarskov received research grants from Astellas Pharma. None of the other authors received external funding for the study.

Authors’ contributions

CK Tolstrup: protocol development, data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing.

G Lose: protocol development, manuscript editing.

N Klarskov: protocol development, data analysis, manuscript editing.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tolstrup, C.K., Lose, G. & Klarskov, N. The Manchester procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy in the treatment of uterine prolapse: a review. Int Urogynecol J 28, 33–40 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3100-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-016-3100-y