Abstract

Several recent studies on the finance–growth nexus highlight that too much financial development, as it has been established in many advanced economies, harms growth. Beck et al. (J Financ Stab 10:50–64, 2014) criticize this literature for only focusing on intermediation activities of financial systems, even though financial sectors in advanced countries have extended their scope beyond traditional tasks. In line with this argument, Beck et al. find for a panel of high-income countries that financial sector size and non-intermediation activity stimulate growth, while intermediation activity has no effect. However, they focus only on OLS regressions with a very limited number of control variables. We test for the robustness of these results. Our findings show that they depend on outliers and are not robust against alternative specifications or estimation approaches. Further, a big financial sector and too many non-intermediation activities are found to reduce growth in some specifications. Our results suggest that Beck et al.’s criticism of the “too much finance” literature is grounded on thin empirical evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Several recent studies question the pre-crisis consensus that more financial development fuels growth. For example, Philippon and Reshef (2013, p. 92) conclude after an in-depth analysis of several developed countries that “it is quite difficult to make a clear-cut case that at the margin reached in high-income economies, the expanding financial sector increases the rate of economic growth.” Masten et al. (2008), based on a sample of European countries, show that less-developed countries gain more from financial development than more developed countries. Bezemer et al. (2014) find a negative relationship between bank credit and growth for 46 mostly developed economies over 1990 to 2011. Rousseau and Wachtel (2011) show for a panel of 84 countries that the finance–growth nexus strongly diminished after the early 1980s. Arcand et al. (2012), Cecchetti and Kharroubi (2012), Law and Singh (2014), and Sturn and Epstein (2014) show for panels of, respectively, 133, 50, 87, and 132 developing and developed countries that the finance–growth nexus is nonlinear, and that the positive growth impact of private credit peaks and turns negative after a threshold value.Footnote 1 Even though these studies apply different estimators on different samples, this threshold level of private credit is estimated to lie broadly around 90 % of GDP in all of them. Such a level was reached in the last two decades by a significant number of developed countries.

Several possible explanations for such a nonlinear finance–growth nexus have been put forward. Aghion et al. (2005) present a growth model where financial development induces catching-up and leads to convergence of long-run growth, as financial constraints prevent poor countries from taking full advantage of technology transfers. Rousseau and Wachtel (2011) link it to financial liberalization and frequent financial crises since the late 1980s. Kneer (2013) shows for 13 advanced countries that financial development leads to brain drain to the financial sector, reducing productivity and value-added growth disproportionally in industries which rely strongly on skilled labor. Hung (2009) argues that unproductive consumption loans can generate such an effect, and Beck et al. (2012) present cross-country evidence that household lending has no growth effect, while firm lending has positive effects (see also Bezemer et al. 2014). Sturn and Epstein (2014) show that non-bank lending, a broad measure for shadow banking, affects growth negatively. Both lending to households and lending by non-bank facilities increased strongly in recent decades.

In a recent article, Beck et al. (2014) challenge this literature by arguing that it focuses only on intermediation and ignores the fact that financial sectors in advanced countries have extended their scope beyond traditional tasks:

[T]he financial sector has gradually extended its scope beyond the traditional activity of intermediation between providers and users of funds toward non-intermediation financial activities. The importance of traditional financial intermediation relative to these non-intermediation financial activities has declined over time as financial institutions have diversified into non-lending activities. [...] As a result, the traditional measures of intermediation activities have become less and less congruent with the reality of modern financial systems and recent papers are not very informative about the effect of financial sector size on growth and volatility. (Beck et al. 2014, p. 51)

Beck et al. (2014) seek to address this issue empirically by including a measure of financial sector size, the value added of the financial sector, as regressor while controlling for traditional intermediation by including bank credit to the private sector in percent of GDP. They interpret financial sector size, when jointly controlling for bank credit, as proxy for financial activities beyond intermediation. Beck et al. (2014, p. 62) find “a positive growth effect of the size of the financial sector and the non-intermediation component in the subsample of high-income countries.” Thus, studies not controlling for such non-intermediation activities might erroneously conclude that the finance–growth nexus became weaker or even negative over time.

Beck et al. (2014) apply a simple OLS estimator. They explain: “[A]s this is an initial exploration [...] we focus on OLS regressions, leaving issues of endogeneity and omitted variable biases for future research.” (Beck et al. 2014, p. 53). Further, they never jointly include all control variables typically used in the literature. In this replication study, we assess the robustness of these results by applying the original data set of Beck et al. (2014). We re-estimate the original specifications, but add all control variables jointly, not one at a time as in Beck et al. (2014). Further we include country and time fixed effects, and test for the impact of outliers. Finally, we address issues of endogeneity for a larger sample of developed and developing countries.

2 Data and empirical approach

The total sample of Beck et al. (2014) covers 77 countries for the period 1980–2007.Footnote 2 Beck et al. (2014) obtain support for their arguments only from high-income countries for the period 1995–2007, while financial sector size is not significant for a larger sample with additional years or more countries. Thus we start out focusing on high-income countries in the years 1995–2007. In further regressions, we then also include the years 1980–1994, and low- and middle-income countries. Following the standard approach in the literature, Beck et al. (2014) average their annual data over non-overlapping 5-year periods.Footnote 3

Following Beck et al. (2014), we investigate the impact of financial sector size and intermediation on growth. Thus, size can be interpreted as capturing all non-intermediation activities, like “proprietary trading, market making, provision of advisory services, insurance and other non-interest income generating activities” (Beck et al. 2014, p. 51). The regression specification has the following form:

Growth is the annual difference in the logarithm of GDP per capita in constant local currency units for country i in time period t. Size is the gross value added of the financial industry as a share of GDP. Intermediation is the logarithm of private credit to GDP. X is a vector of control variables typically included in the growth literature (e.g., Arcand et al. 2012). It consists of the logarithm of real Initial GDP per capita at the beginning of each 5-year episode, Education, measured as average years of schooling of the population above 25 years of age, Inflation, the growth rate of the consumer price index, Openness, constructed as imports and exports as a share of GDP, and Government consumption as a share of GDP (see the Appendix for summary statistics of the variables included).

3 Developed economies, 1995–2007

3.1 Specification details

Our first specification for a sample of developed countries from 1995 to 2007 follows exactly Beck et al. (2014). We estimate Eq. (1) by OLS, controlling for Initial GDP, Education, and Inflation. Our second specification includes two standard control variables, Openness and Government Consumption, as further regressors. We also include time dummies to control for common unobserved shocks to all countries. Beck et al. (2014) report that they tested for the robustness of their results when including time and/or country fixed effects for the full sample of developed countries. However, they do not test these effects on the sample of developed countries only.

In the third specification, we additionally purge country fixed effects, to control for unobserved heterogeneity of the countries. Note that we explain growth of GDP, and include GDP at the beginning of each 5-year episode as explaining factor, which might be interpreted as dynamic panel.Footnote 4 As the fixed effects estimator yields biased results in a dynamic panel setting, especially in short panels (Nickell 1981), we apply the bias-corrected least-squares dummy variable estimator described in Bruno (2005a and 2005b).Footnote 5

In the fourth specification, we follow Arcand et al. (2012) and others, and include the squared terms of Intermediation and/or Size as further regressors. This allows us to test whether the effect of financial development on growth is nonlinear. More specifically, we are interested in seeing if a big financial sector diminishes growth.

3.2 Results

We start our analysis by obtaining an exact replication of the first specification in Table 9 of Beck et al. (2014).Footnote 6 To get there, we estimate Eq. (1) by OLS, including Initial GDP, Education, and Inflation as control variables. The results are presented in Table 1, Specification 1. We find that Intermediation is insignificantly negatively correlated with growth, while Size is highly significantly and positively correlated.

Following Beck et al. (2014), this suggests that financial development contributes to growth in rich countries where the amount of bank credit as a share of GDP is already high, and that the driving force behind this effect is related to non-intermediation activities. Thus, studies focusing only on intermediation activities might mistakenly conclude that the finance–growth nexus diminishes in rich countries.

However, as we will see, this result is not robust along several dimensions. Including Openness, Government Consumption, and time dummies as further controls (Specification 2) reduces the coefficient and significance level of Size noticeable, but it is still significant at the 10 % level, while Intermediation remains insignificant. Once fixed effects are purged, Size becomes negatively insignificantly correlated with growth, while Intermediation even becomes negatively significant (Specification 3). When testing for a nonlinear impact of credit and financial sector size, we do not find much support for such effects. Neither Size or Intermediation, nor their squared terms are statistically significant or have coefficients with the expected signs (Specification 4). So far, we seem to find some modest support for the case of Beck et al. (2014).

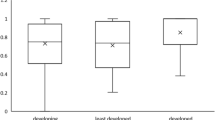

A closer inspection of the data yields that Luxembourg is a huge outlier in terms of financial sector size (Fig. 1). The sample mean of financial sector value added as a percentage of GDP lies at 6.1, with a standard deviation of 3.9, while the observations for Luxembourg reach values between 21.7 and 27.2. Thus, Luxembourg is four to five and a half standard deviations away from the sample mean of developed countries. To assess the significance of Luxembourg on the overall findings, we re-estimate Specifications 1–4 without Luxembourg (see Specifications 5–8). This strongly weakens the evidence in support of Beck et al. (2014). Size is only statistically significant, and only at the 10 % level, in the rudimentary OLS specification (Specification 5). In all augmented specifications it is insignificant, with coefficients close to zero once country fixed effects are purged. Intermediation is always insignificant with a negative sign. We further find negative signed squared terms of Size and Intermediation, but both are insignificant.

Scatter plot between Growth and Size for 27 developed countries, 1995–2007 (5-year averages). Source: Beck et al. 2014, own presentation

Finally, Specifications 9–12 repeat this analysis but only include Size as a measure of financial development. It might be that Intermediation and Size are correlated, and thus that multicollinearity issues are responsible for the mostly insignificant coefficients of Size and Intermediation. The results, however, are largely identical to Specifications 5–8, with the difference that Size is now always statistically insignificant. Overall, the results of Beck et al. (2014) are not robust against reasonable modifications in the specifications, like the inclusion of additional covariates typically included in the literature, purging fixed effects, and the omission of outliers.

3.3 Additional evidence for different measures of financial sector size

We present results for additional proxies of financial sector size obtained from the EU KLEMS database for the same sample of developed countries for the period 1995–2007. Specifically, we include financial sector employment as a share of total employment, hours worked in the financial sector as a share of total hours worked, and the compensation share of the financial sector as alternative proxies for financial sector size.

Beck et al. (2014, p. 62) find “that size while controlling for intermediation is positively and significantly associated with growth. This holds across all four indicators of financial sector size—value added share, compensation share, employment share and share hours. [...] This shows that our results do not depend on the specific size measure used in the main analysis.”

Table 2 summarizes our results for the four different specifications with each of the alternative financial size proxies. To save space, we do not present the coefficients and p values of the control variables included in the specifications. Specification 13 of Panel A to C provides exact replications of the first column in Table 9 of Beck et al. (2014). We find that all three alternative proxies for financial sector size—Employment Share, Hours Share, and Compensation Share—yield a statistically highly significant positive effect on growth.

However, also this result is not robust. Once time dummies and other control variables typically included in the literature are added, the coefficients of Employment share, Hours share, and Compensation share are substantially lower and the significance is gone (Specification 14). Once fixed effects are purged (Specification 15), their coefficients drop basically to zero. When testing for nonlinearities, all financial development proxies are insignificant (Specification 16). Intermediation is insignificant in all specifications. In sum, minor changes in the specifications of Beck et al. (2014) alter the central outcomes considerably.

We proceed by excluding Luxembourg from the sample, and re-estimate these four specifications for three proxies of financial sector size (Table 2, Specifications 17–20).Footnote 7 In Specifications 17–19, we find a statistically insignificant coefficient for all three alternative financial size proxies, as well as Intermediation.

Once we allow for a nonlinear impact of the financial sector size proxies in Specification 20, we find a statistically significant positive coefficient of Employment Share and Hours Share, and a significantly negative coefficient of Employment Share Squared and Hours Share Squared. This suggests that the positive growth impact of the employment and hours share diminishes, and turns negative after reaching a threshold value. This threshold is estimated to lie at 2.3 for the Employment Share and 2.6 for the Hours Share.Footnote 8 Given that the sample means of Employment Share and Hours Share are at 2.7, in both cases, this result implies that financial sector size is a drag on growth in more than half of the sample. Or to illustrate this result differently, 15 (14) of the 26 countries in the sample have an Employment Share (Hours Share) above the threshold level in the last period where data are available. The estimates with Compensation Share point in a similar direction, but are insignificant.

To assess the robustness of these results, we exclude Intermediation from the set of explanatory variables (Specifications 21–24). The results remain very similar to Specifications 17–20. Employment Share and Hours Share are again found to show a nonlinear impact on growth. Also the threshold values remain virtually identical. These findings are much more consistent with the “too much finance” view than with the outline of Beck et al. (2014).

4 Developed and developing economies, 1980–2007

4.1 Specification details

As causality might also run from growth to financial development, addressing issues of endogeneity is of particular concern in the finance–growth literature (e.g., Levine 2005). Thus, once we move to the full sample of 77 countries for the period 1980–2007, we follow the standard approach in the growth literature when dealing with “large N, small T” samples with endogenous regressors, and apply the system GMM estimator (see Arellano and Bover 1995; Blundell and Bond 1998) with the asymptotically more efficient two-step procedure described in Arellano and Bond (1991) and the Windmeijer (2005) finite sample correction. The Hansen test of overidentifying restrictions and the Arellano–Bond serial correlation test are reported with the regression results.Footnote 9 To avoid bias due to instrument proliferation (see Roodman 2009), we limit the lag-length of the instrumental variables, allowing for a maximum of three lags.Footnote 10

Specifications 25 and 26 in Table 3 include the whole sample of 77 countries with and without squared terms for Size and Intermediation. Specifications 27 and 28 exclude Luxembourg, and Specifications 29 and 30 further exclude Intermediation and Intermediation squared from the list of regressors.

4.2 Results

The results are presented in Table 3 and confirm our previous finding that financial sector size does not contribute to higher growth. In line with Beck et al. (2014), who only provide OLS estimates, we do not find any evidence for a growth-enhancing effect of financial sector size or non-intermediation activity once the sample size is increased across time and over countries.Footnote 11 Size is highly insignificant, mostly with a negative coefficient, as is Size Squared. Also Intermediation is always statistically insignificant with a negative coefficient. In line with the “too much finance” view, once Intermediation Squared is included, Intermediation becomes positive, while Intermediation Squared affects growth negatively, but both terms are statistically insignificant.

To sum up, we find no empirical support for the view that financial sector size or non-intermediation activity significantly contributes to growth in recent decades for this larger sample. While this finding deviates from the results of several previous studies, which found strong growth-enhancing effects of financial development (e.g., Levine et al. 2000; Beck and Levine 2004; for studies challenging the robustness of these findings see, e.g., Favara 2003; Roodman 2009), it is consistent with the more recent literature, arguing that the finance–growth nexus strongly vanished in recent decades (e.g., Rousseau and Wachtel 2011; Arcand et al. 2012; Sturn and Epstein 2014).

5 Conclusion

Beck et al. (2014) argue that studies only focusing on intermediation activities of financial systems underestimate their growth effect especially in developed countries. We reassess the impact of financial intermediation, financial sector size, and financial non-intermediation activity on growth in developed countries by including additional control variables, excluding outliers, and apply different estimation techniques. We do not find a robust, statistically significant, and positive growth effect of financial sector size or non-intermediation activity. In fact, financial sector size and non-intermediation activity are generally found to be insignificant, with coefficients close to zero. Once we allow for a nonlinear effect of financial sector size and non-intermediation activity on growth, we find some support for the argument that big financial systems may harm growth in developed countries.

We also reassess the effects of financial sector size and non-intermediation activity on growth for developed and developing countries, thereby also addressing issues of endogeneity. In line with Beck et al. (2014), we find no evidence that size or non-intermediation activity fuels growth for this larger sample. If anything, our overall results tentatively support the “too much finance” view, while soundly refuting the interpretation of Beck et al. (2014).

Notes

Arcand et al. (2012) show that this finding also holds for industry-level data.

Beck et al. (2014) drop all observations after 2007. They justify this as follows: “Although the potential instability associated with a large financial sector is central to our argument, we exclude the recent crisis from the sample period in order to be able to draw more general conclusions. Given the sudden large output declines which are reflected in the data as from 2008, results would be dominated by this event.” (Beck et al. 2014, p. 53) This is to say, they include the observations covering the years of the buildup of the financial bubble, where financial development went hand in hand with high but unsustainable growth, but exclude the period of the correction of the bubble. This seems problematic; such a decision potentially biases the results.

This is done to sweep out business cycle fluctuations from the data. Because proxies for financial development are highly pro-cyclical, it is important to address this issue. Sturn and Epstein (2014) show that 5-years averaging does not successfully sweep out business cycle effects, and therefore potentially biases results.

To see why, consider that Growth is defined as \(\varDelta y=y_{t}-y_{t-1}\), where y is GDP in logarithms. Thus, Eq. (1) can be rewritten as \(y_{t}-y_{t-1}={\upbeta }_{1}y_{t-1}+{\upbeta }_{2}W_{it}+{\upvarepsilon }_{it}\), which is identical to \(y_{t} = ({\upbeta }_{1}+1)y_{t-1}+{\upbeta }_{2}W_{it}+{\upvarepsilon }_{it}\) (see Bond et al. 2001).

We choose the Blundell and Bond (1998) estimator, designed for highly persistent series as in our case, to initialize the bias correction. However, our results are robust against the use of the Arellano and Bond (1991) estimator instead. Following standard practice when applying this estimator, we estimate standard errors using a parametric bootstrap method (see Bruno 2005b) with 400 resamples. To avoid loosing one observation per country when applying this dynamic estimator, we merge data on real GDP in local currency units from the World Development Indicators (WDI). Thus, Initial GDP in specifications applying the bias-corrected LSDV estimator slightly differs from Initial GDP in the OLS specifications, where it is defined as real GDP per capita in US dollars as in the original data set. All our central findings also hold when applying the uncorrected least-squares dummy variable estimator on the original data set. When applying the system GMM estimator, the coefficients are very imprecisely estimated and all variables measuring financial development are statistically insignificant in all specifications.

Luxembourg is also an outlier regarding Employment share, Hours share, and Compensation share.

This result is confirmed if estimated by the fixed effects estimator, whereas the thresholds are found to lie at 2.5 and 2.8, respectively.

The Hansen tests never reject the null, and thus provide support for the validity of the instruments. All regressions reject the null of no first-order autocorrelation, and do not reject the null of no second-order autocorrelation.

We treat Education, Openness, and Government Consumption as exogenous. We also experimented with various other specifications—e.g., treating all explaining variables as endogenous, allowing for more or less lags as instruments, collapsing the instrument matrix—with qualitatively similar results.

This result also holds when applying the OLS or fixed effects estimator.

References

Aghion P, Howitt P, Mayer-Foulkes D (2005) The effect of financial development on convergence: theory and evidence. Q J Econ 120(1):173–222

Arcand J-L, Berkes E, Panizza U (2012) Too much finance? IMF Working Paper 12/161, IMF, Washington

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Arellano M, Bover O (1995) Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J Econom 68(1):29–51

Beck T, Büyükkarabacak B, Rioja FK, Valev NT (2012) Who gets the credit? And does it matter? Household vs. firm lending across countries. B.E J Macroecon 12(1):1–46

Beck T, Degryse H, Kneer C (2014) Is more finance better? Disentangling intermediation and size effects of financial systems. J Financ Stab 10:50–64

Beck T, Levine R (2004) Stock markets, banks, and growth: panel evidence. J Bank Finance 28(3):423–442

Bezemer D, Grydaki M, Zhang L (2014) Is financial development bad for growth? SOM Research Report 14016

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econom 87(1):115–143

Bond SR, Hoeffler A, Temple J (2001) GMM estimation of empirical growth models. CEPR Discussion Papers 3048

Bruno GSF (2005a) Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Econ Lett 87(3):361–366

Bruno GSF (2005b) Estimation and inference in dynamic unbalanced panel-data models with a small number of individuals. Stata J 5(4):473–500

Cecchetti S, Kharroubi E (2012) Reassessing the impact of finance on growth. BIS Working Papers 381

Favara G (2003) An empirical reassessment of the relationship between finance and growth. IMF Working Paper 03/123, IMF, Washington

Hung F-S (2009) Explaining the nonlinear effects of financial development on economic growth. J Econ 97(1):41–65

Kneer C (2013) Finance as a magnet for the best and brightest: implications for the real economy. De Nederlandsche Bank Working Papers 392

Law SH, Singh N (2014) Does too much finance harm economic growth? J Bank Finance 41(C):36–44

Levine R (2005) Finance and growth: theory and evidence. In: Aghion P, Durlauf NS (eds) Handbook of economic growth, vol 1, part A, pp 865–934. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Levine R, Loayza N, Beck T (2000) Financial intermediation and growth: causality and causes. J Monet Econ 46(1):31–77

Masten AB, Coricelli F, Masten I (2008) Non-linear growth effects of financial development: does financial integration matter? J Int Money Finance 27(2):295–313

Nickell SJ (1981) Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica 49(6):1417–1426

Philippon T, Reshef A (2013) An international look at the growth of modern finance. J Econ Perspect 27(2):73–96

Roodman D (2009) A note on the theme of too many instruments. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 71(1):135–158

Rousseau PL, Wachtel P (2011) What is happening to the impact of financial deepening on economic growth? Econ Inq 49(1):276–288

Sturn S, Epstein GA (2014) Finance and growth: the neglected role of the business cycle. PERI Working Paper 339

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. J Econom 126(1):25–51

Acknowledgments

We thank Jesus Crespo Cuaresma for very helpful econometric suggestions, and Thorsten Beck for generously sharing his data. Remaining errors are ours. Financial support from the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Anniversary Fund (Grant No. 15330) is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sturn, S., Zwickl, K. A reassessment of intermediation and size effects of financial systems. Empir Econ 50, 1467–1480 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-0979-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-015-0979-y